Russian Analytical Digest No 110: Presidential Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Russia Trying to Defend? ✩ Andrei Yakovlev

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Russian Journal of Economics 2 (2016) 146–161 www.rujec.org What is Russia trying to defend? ✩ Andrei Yakovlev Institute for Industrial and Market Studies, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia Abstract Contrary to the focus on the events of the last two years (2014–2015) associated with the accession of Crimea to Russia and military conflict in Eastern Ukraine, in this study, I stress that serious changes in Russian domestic policy (with strong pres sure on political opposition, state propaganda and sharp anti-Western rhetoric, as well as the fight against “foreign agents’) became visible in 2012. Geopolitical ambitions to revise the “global order” (introduced by the USA after the collapse of the USSR) and the increased role of Russia in “global governance” were declared by leaders of the country much earlier, with Vladimir Putin’s famous Munich speech in 2007. These ambitions were based on the robust economic growth of the mid-2000s, which en couraged the Russian ruling elite to adopt the view that Russia (with its huge energy resources) is a new economic superpower. In this paper, I will show that the con cept of “Militant Russia” in a proper sense can be attributed rather to the period of the mid-2000s. After 2008–2009, the global financial crisis and, especially, the Arab Spring and mass political protests against electoral fraud in Moscow in December 2011, the Russian ruling elite made mostly “militant” attempts to defend its power and assets. © 2016 Non-profit partnership “Voprosy Ekonomiki”. Hosting by Elsevier B.V. -

RUSSIA INTELLIGENCE Politics & Government

N°66 - November 22 2007 Published every two weeks / International Edition CONTENTS KREMLIN P. 1-4 Politics & Government c KREMLIN The highly-orchestrated launching into orbit cThe highly-orchestrated launching into orbit of of the «national leader» the «national leader» Only a few days away from the legislative elections, the political climate in Russia grew particu- STORCHAK AFFAIR larly heavy with the announcement of the arrest of the assistant to the Finance minister Alexey Ku- c Kudrin in the line of fire of drin (read page 2). Sergey Storchak is accused of attempting to divert several dozen million dol- the Patrushev-Sechin clan lars in connection with the settlement of the Algerian debt to Russia. The clan wars in the close DUMA guard of Vladimir Putin which confront the Igor Sechin/Nikolay Patrushev duo against a compet- cUnited Russia, electoral ing «Petersburg» group based around Viktor Cherkesov, overflows the limits of the «power struc- home for Russia’s big ture» where it was contained up until now to affect the entire Russian political power complex. business WAR OF THE SERVICES The electoral campaign itself is unfolding without too much tension, involving men, parties, fac- cThe KGB old guard appeals for calm tions that support President Putin. They are no longer legislative elections but a sort of plebicite campaign, to which the Russian president lends himself without excessive good humour. The objec- PROFILE cValentina Matvienko, the tive is not even to know if the presidential party United Russia will be victorious, but if the final score “czarina” of Saint Petersburg passes the 60% threshhold. -

Inside and Around the Kremlin's Black Box

Inside and Around the Kremlin’s Black Box: The New Nationalist Think Tanks in Russia Marlène Laruelle STOCKHOLM PAPER October 2009 Inside and Around the Kremlin’s Black Box The New Nationalist Think Tanks in Russia Marlène Laruelle Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden ww.isdp.eu Inside and Around the Kremlin’s Black Box: The New Nationalist Think Tanks in Rus- sia is a Stockholm Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Stockholm Papers Series is an Occasional Paper series addressing topical and timely issues in international affairs. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy- watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication is kindly made possible by support from the Swedish Ministry for For- eign Affairs. The opinions and conclusions expressed are those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute for Security and Development Policy or its sponsors. © Institute for Security and Development Policy, 2009 ISBN: 978-91-85937-67-7 Printed in Singapore Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. +46-841056953; Fax. -

What Is Russia Trying to Defend?

BOFIT Policy Brief 2016 No. 2 Andrei Yakovlev What is Russia trying to defend? Bank of Finland, BOFIT Institute for Economies in Transition BOFIT Policy Brief Editor-in-Chief Iikka Korhonen BOFIT Policy Brief 2/2016 Andrei Yakovlev: What is Russia trying to defend? 21.1.2016 ISSN 2342-205X (online) Bank of Finland BOFIT – Institute for Economies in Transition PO Box 160 FIN-00101 Helsinki Phone: +358 10 831 2268 Fax: +358 10 831 2294 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bof.fi/bofit_en The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Finland. Andrei Yakovlev What is Russia trying to defend? Contents 1 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1 Prehistory of the ‘turnaround’ in Russia’s relations with the West .............................................. 4 2 Main features of the ‘new course’ ................................................................................................ 6 3 Impact of ‘new course’ on behavior of economic actors .............................................................. 8 4 Resources, opportunities and restrictions to development .......................................................... 11 5 Concluding remarks .................................................................................................................... 14 References ......................................................................................................................................... -

Business Programme for the Fourth Eastern Economic Forum BUSINESS PROGRAMME for the FOURTH EASTERN ECONOMIC FORUM 11–13 September 2018, Vladivostok

Business Programme for the Fourth Eastern Economic Forum BUSINESS PROGRAMME FOR THE FOURTH EASTERN ECONOMIC FORUM 11–13 September 2018, Vladivostok Programme accurate as at September 7, 2018 11 September 2018 09:00–11:00 Joint Meeting of Russia–Korea and Korea–Russia Business and Investment Councils Building A, level 11 By personal invitation only Business breakfast hall Political and economic cooperation between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Korea is on an unprecedented rise. The Moon Jae-in Administration has set Korea–Russia relations as one of its key priorities, resulting in the 'Nine Bridges towards Cooperation' initiative. How the private sector could be involved in the “Nine Bridges” initiative implementation? Which sectors could become locomotives for boosting bilateral trade and investment? What role might SMEs assume in this process? Moderator: Sergey Glukhov, General Director, Leaders' Club Panellists: Artem Avetisyan, Director of the New Business Department, Agency for Strategic Initiatives; Chairman of the Non-Governmental Organization Leaders' Club Svetlana Chupsheva, Chief Executive Officer, Agency for Strategic Initiatives Jaeho Jung, Member of Parliament of the Republic of Korea; Special Advisor, Presidential Committee on Northern Economic Cooperation Homin Kang, Senior Vice President, Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry Sergei Kelbakh, Chairman of the Board, Russian Highways State Company Oleg Kozhemyako, Governor of Sakhalin Region Pyung-oh Kwon, President, Chief Executive Officer, Korea Trade-Investment -

Russia by Pavel Luzin

Russia by Pavel Luzin Capital: Moscow Population: 144.1 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$23,770 Source: World Bank World Development Indicators. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2017 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 National Democratic 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 Governance Electoral Process 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Civil Society 5.50 5.75 5.75 5.50 5.25 5.50 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.50 Independent Media 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.50 Local Democratic 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 Governance Judicial Framework 5.25 5.50 5.50 5.75 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.50 and Independence Corruption 6.00 6.25 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Democracy Score 5.96 6.11 6.14 6.18 6.18 6.21 6.29 6.46 6.50 6.57 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. If consensus cannot be reached, Freedom House is responsible for the final ratings. The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. -

Business Quarterly Association of European Businesses

AEB Business Quarterly Association of European Businesses Quality Information • Eff ective Lobbying • Valuable Networking Spring 2013 1010 yearsyears ofof HRHR inin Russia:Russia: AchievementsAchievements && ProspectsProspects With AEB updates on: HR market in Russia / The role of HR leaders in change management / Updates on employment law in Russia / Updates of the Russian state pension system / AEB Networking…and more НАБОР ПЕРСОНАЛА ПРОФЕССИОНАЛЬНАЯ МОБИЛЬНОСТЬ ОБУЧЕНИЕ Благодаря тестам TOEIC©, Ваш успех гарантирован! Тесты TOEIC© являются индикатором истинных знаний английского языка Ваших настоящих и будущих сотрудников, а также помогают в принятии решений по набору персонала. Подробнее : www.etsglobal.org Copyright© 2013 by Educational Testing Service. All rights reserved. ETS, Advetising the ETS logo and TOEIC are registered trademarks of Educational Testing Service (ETS), and used under license. 1 Dear Friends, Welcome to the Spring edition of the AEB Business Quarterly, which is dedicated to the HR industry in Russia. Globalization and the rapid advance of information technology have deeply aff ected the polit- ical and socio-economic environment, creating new opportunities along with new challenges. Now it is evident that to address emerging needs and combat upcoming challenges, businesses need to master the “human element” of change. In recent years we have seen signifi cant changes in the fi eld of human resources. Th eir role has grown considerably, and they are now recognized as a key function infl uencing business strategy. Russia’s markets are growing in volume so it is crucial for companies to understand what they should do to be an attractive employer and to manage eff ectively. According to the AEB–Gfk survey conducted in 2012, qualifi ed personnel along with large market potential and positive market developments are the key factors which attract foreign investment. -

Russia–Africa Economic Forum Programme

Russia–Africa Economic Forum Forum Programme RUSSIA–AFRICA ECONOMIC FORUM PROGRAMME October 23-24, 2019, Sochi Programme accurate as at October 24, 2019 23 October 2019 10:00–13:00 Plenary session Russia and Africa: Uncovering the Potential for Cooperation Forum plenary hall Address by the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin Address by the President of the Arab Republic of Egypt Abdelfattah Al-Sisi Moderator: Irina Abramova, Director, Institute for African Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Corresponding Member, Russian Academy of Sciences Panellists: H.E. Amani Abou-Zeid, Commissioner for Infrastructure and Energy, African Union Commission Dmitry Kobylkin, Minister of Natural Resources and Environment of the Russian Federation Andrey Kostin, President and Chairman of the Management Board, VTB Bank Phuthi Mahanyele-Dabengwa, Chief Executive Officer, Naspers Ltd Benedict Okey Oramah, President, Chairman of the Board of Directors, African Export– Import Bank (Afreximbank) Maxim Oreshkin, Minister of Economic Development of the Russian Federation Andrey Slepnev, Chief Executive Officer, Russian Export Center Stergomena Lawrence Tax, Executive Secretary, Southern African Development Community (SADC) 12:00–13:00 Plenary session Introducing Russia to Africa Forum plenary hall African economies are currently striving to achieve inclusive growth and sustainable development – efforts which must be supported by constant technological progress. Today’s global technological landscape is becoming increasingly digital, -

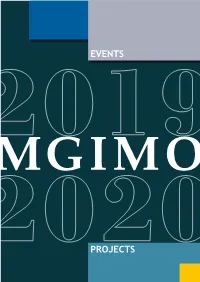

Endowment and MGIMO Alumni Association

EVENTS MGIMO PROJECTS MGIMO Key Indicators 1 “5 STARS” in QS Stars MGIMO ranked FIRST in the QS Graduate Employability Ranking MGIMO applicants’ average GPA on the Unified State Exam 96,2 MGIMO is a Russian 16% of the students education exporter enrolled are foreigners 4 5 More than 200 cooperation agreements with foreign partners from 57 countries International AMBA “The second generation” accreditation of MGIMO educational standards Autonomous Dissertation Councils and the right to confer academic degrees Schools Institutes campuses: Vernadsky Campus 8536 students, 8 3 2 221 graduate students & MGIMO Campus departments languages in Odintsovo 77 53 1193 students MGIMO Branch in Tashkent 88 students Gorchakov Lyceum School of Business and International Proficiency faculty members, 1254 including 11 full members and corresponding Journals peer-reviewed by the members of the Russian Academy Higher Attestation Commission, of Sciences, Scopus and Web of Science 5 professors of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 12 honoured workers of science, MGIMO Endowment 242 Drs. habil Fund’s capital 715 Ph.Ds roubles $271,7 mln bln MGIMO graduates 50 000 The major events in Events for 2019: Alumni th ▶ 75 MGIMO Anniversary each year more than ▶ Launching MGIMO branch in Tashkent 40 ▶ ALUMNI forum in Tashkent ▶ 12 RISA Convention foreign MGIMO ▶ 25th Anniversary of the School Alumni33 clubs of Governance and Politics ▶ “Trianon Dialogue” ▶ “Sochi Dialogue” Educational Programmes and Admissions Results Bachelor’s Degree Programmes Master’s Degree Programmes -

KAZAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW Volume 2, Autumn 2017, Number 3

KAZAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW Volume 2, Autumn 2017, Number 3 Journal President: Ildar Tarkhanov (Kazan Federal University, Russia) Journal Editor-in-Chief: Damir Valeev (Kazan Federal University, Russia) International Editorial Council: Russian Editorial Board: Sima Avramović Aslan Abashidze (University of Belgrade, Serbia) (Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, Susan W. Brenner Russia) (University of Dayton School of Law, USA) Adel Abdullin William E. Butler (Kazan Federal University, Russia) (The Pennsylvania State University, USA) Lilia Bakulina Michele Caianiello (Kazan Federal University, Russia) (University of Bologna, Italy) Igor Bartsits Peter C.H. Chan (The Russian Presidental Academy (City University of Hong Kong, China) of National Economy and Public Hisashi Harata Administration, Russia) (University of Tokio, Japan) Ruslan Garipov Tomasz Giaro (Kazan Federal University, Russia) (University of Warsaw, Poland) Vladimir Gureev Haluk Kabaalioğlu (Russian State University of Justice (Yeditepe University, Turkey) (RLA Russian Justice Ministry), Russia) Gong Pixiang Pavel Krasheninnikov (Nanjing Normal University, China) (State Duma of the Russian Federation, William E. Pomeranz Russia) (Kennan Institute, USA) Valery Lazarev Ezra Rosser (The Institute of Legislation (American University Washington College of Law, USA) and Comparative Law under the Government George Rutherglen of the Russian Federation, Russia) (University of Virginia, USA) Ilsur Metshin Franz Jürgen Säcker (Kazan Federal University, Russia) (Free University of Berlin, Germany) Anatoly Naumov Paul Schoukens (Academy of the Prosecutor's Office (KU Leuven, Belgium) of the Russian Federation, Russia) Carlos Henrique Soares Zavdat Safin (Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais, Brazil) (Kazan Federal University, Russia) Jean-Marc Thouvenin Evgeniy Vavilin (Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense University, France) (Saratov State Academy of Law, Russia) KAZAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW . -

Is Russia an Arctic Status Quo Power? Morten Larsen Nonboe Phd-Studerende, Institut for Statskundskab, Aarhus Universitet, Email: [email protected]

Is Russia an Arctic Status Quo Power? Morten Larsen Nonboe phd-studerende, Institut for Statskundskab, Aarhus Universitet, email: [email protected]. Russian foreign policy in the increasingly impor- 10, Zyśk 2009: 106, Trenin 2010: 10-12, Indzhiyev 2010: tant Arctic region refl ects an ambiguous combi- 117-118). Specifi cally, the approach stresses that Russia nation of assertiveness and cooperation in accor- bases its claims in the ice-covered Arctic Ocean on the dance with international law. Against this back- UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)1 and ground, the existing literature on the Arctic tends has abrogated the Soviet sector principle according to to polarise around revisionist and status quo in- which the Soviet Union unilaterally claimed a triangu- lar sector between the Soviet Union’s North-eastern and terpretations of Russian foreign policy in the re- North-western borders and the North Pole in 1926 (In- gion. Based on case studies this article provides dzhiyev 2010: 16-20, Kazmin 2010: 15). Th e approach support for a modifi ed version of the status quo also highlights Russia’s participation in the ‘Arctic Five’ interpretation which incorporates insights from cooperation with the other Arctic coastal states (Canada, the revisionist interpretation. Denmark, Norway, and the United States). Th e ‘Arctic Five’ cooperation is based on the UNCLOS and was 1. Russia and the Arctic formally launched at the Ilulissat Summit in May 2008 Th e existing literature on Russian foreign policy in the when the ‘Arctic Five’ signed the Ilulissat Declaration and Arctic is divided into two competing camps.