January 26, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brochure Dubbed 140909

Andhi Toofan Director : Chi Gurudutt Music : Vidyasagar Aaj Ka Krantiveer Year of release : 2008 Cast : Sudeep, Vaibhavi, Pooja Gandhi Director : Uday Shankar Synopsis : Kamanna (Doddanna) has brought up Ramanna (Sudeep) and Kittanna (Rockline Venkatesh) Music : Vidyasagar from childhood. All the three are efficient thieves. One fine day they all decide to give up their Year of release : 2001 profession of stealing and settle down in some other place. They are traveling in a lorry that develops mechanical defect in the midst of a forest on a dark night. Luckily, they find a house in the next Cast : Vijaykanth, Soundarya morning to live. This is the house of Kanaka (Vaibhavi). Her father is facing a difficult situation in front Synopsis : Vijaykant plays the role of a respected village elder Thavasi, whose word is law. He also of the village chieftain. The stay of trio in this house gives some relief and courage to the distressed plays the younger character too, that of Bhoopathy, Thavasi's son where he gets to romance - sing family. The trio - Kamanna and his two sons barge in to the chieftain's house to resolve the litigation further angers the village chieftain. and dance, and fight too. Soundarya, is cast as his fiance, whereas Jayasudha plays Thavasi's wife The trio decides to stay in this village thereafter doing cultivation. In a village fair, Ramanna ties the mangalasutra to Gayathri, daughter of and Nasser plays Pandy, Thavasi's brother-in-law and the villain of the piece. village chieftain. The village chieftain give up his harshness for the sake of his daughter Gayathri. -

Retrospective Analysis of Plagiaristic Practices Within a Cinematic Industry in India – a Tip in the Ocean of Icebergs

Retrospective analysis of plagiaristic practices within a cinematic industry in india – a tip in the ocean of icebergs Item Type Article Authors Sivasubramaniam, Shiva D; Paneerselvam, Umamaheswaran; Ramachandran, Sharavan Citation Umamaheswaran, P., Ramachandran, S. and Sivasubramaniam, S.D., (2020). 'Retrospective Analysis of Plagiaristic Practices within a Cinematic Industry in India–a Tip in the Ocean of Icebergs'. Journal of Academic Ethics, pp.1-11. DOI: 10.1007/ s10805-020-09360-7 DOI 10.1007/s10805-020-09360-7 Publisher Springer Journal Journal of Academic Ethics Download date 27/09/2021 02:43:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/624527 Journal of Academic Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-020-09360-7 Retrospective Analysis of Plagiaristic Practices within a Cinematic Industry in India – aTip in the Ocean of Icebergs Paneerselvam Umamaheswaran1 & Sharavan Ramachandran2 & Shivadas D. Sivasubramaniam3 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Music plagiarism is defined as using tune, or melody that would closely imitate with another author’s music without proper attributions. It may occur either by stealing a musical idea (a melody or motif) or sampling (a portion of one sound, or tune is copied into a different song). Unlike the traditional music, the Indian cinematic music is extremely popular amongst the public. Since the expectations of the public for songs that are enjoyable are high, many music directors are seeking elsewhere to “borrow” tunes. Whilst a vast majority of Indian cinemagoers may not have noticed these plagiarised tunes, some journalists and vigilant music lovers have noticed these activities. This study has taken the initiative to investigate the extent of plagiaristic activities within one Indian cinematic music industry. -

CSIR- CENTRE for CELLULAR and MOLECULAR BIOLOGY (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research) Uppal Road, Habsiguda, Hyderabad - 500 007, Telangana

CSIR- CENTRE FOR CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research) Uppal Road, Habsiguda, Hyderabad - 500 007, Telangana. website: https://www.ccmb.res.in NOTICE Sub.: List of shortlisted and not recommended candidates for interview Ref.: CSIR-CCMB Advt. No. 04/2020-recruitment of scientific positions Post Code: S 01 Senior Principal Scientist: 01 post (Unreserved) Screening criteria adopted by the screening committee is: Essential and Desirable qualifications as per the advertisement. Based on the above mentioned screening criteria adopted by the duly constituted screening committee, the list of shortlisted candidates to be called for interview is as follows: S. No. Application Number Name of the candidate 1 4201032 Dr. Sushmita De 2 4201037 Dr. Maddika Venkata Subba Reddy 3 4201241 Dr. Gayatri Venkataraman 4 4201286 Dr. Manjunath B Joshi The following applicants are not shortlisted for interview for the reasons indicated against each: S. Application Name of the candidate Reasons for rejection No. Number 1 4201067 Dr. Harish Chandra Thakur No DQ 2 4201164 Dr. Arun Kumar Haldar No DQ 3 4201174 Dr. Madhumohan No EQ and particulars of fee paid were not mentioned 4 4201195 Dr. Sanjay Kumar No DQ 5 4201196 Dr. Sreenivasulu Reddy Basireddy No DQ 6 4201259 Dr. Sanjeev Kumar No EQ 7 4201268 Dr. Sreenivasulu Kilari No DQ 8 4201284 Dr. Sai Varsha MKN No DQ 9 4201285 Dr. P Pavan Kumar No DQ and Overage 10 4201297 Dr. Masum Saini No DQ 11 4201329 Dr. Arumugam Rajavelu No DQ 1 | P a g e 12 4201334 Dr. Prasanna Latha Seelam No EQ 13 4201398 Dr. -

LIST of MEDALS and PRIZES to BE AWARDED at the 95Th CONVOCATION of the UNIVERSITY to BE HELD on 3Rd March, 2013

BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY LIST OF MEDALS AND PRIZES TO BE AWARDED AT THE 95th CONVOCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY TO BE HELD ON 3rd March, 2013. FACULTY OF S.V.D.V (THESE MEDALS WILL BE OF SILVER WITH HEAVY GOLD PLATING) 1. Griffith Ramayan Medal Awarded to Shri Alok Kumar Pandey for standing First at the Shastri (Hons.) Examination 2012. 2. Prof. Rajmohan Upadhyay Memorial Awarded to Shri Raja Pathak for securing highest Gold Medal marks with Jyotish subject in the Shastri (Hons.) Exam., 2012. 3. B.H.U. Medal Awarded to Shri Alok Kumar Pandey for standing First at the Shastri (Hons.) Examination 2012. 4. B.H.U. Medal Awarded to Shri Manu Mishra ifor standing First in Mimansha at the Acharya Examination 2012. 5. B.H.U. Medal Awarded to Shri Manish Tiwari for standing First in Jyotish at the Acharya Examination 2012. 6. B.H.U. Medal Awarded to Shri Mulagaleti K. Sriram for standing First in Vaidic Darshan(Puraneitihash) at the Acharya Examination 2012. 7. B.H.U. Medal Awarded to Shri Yogesh Chandra Pargai for standing First in Sahitya at the Acharya Examination 2012. 8. B.H.U. Medal Awarded to Km. Deepika for standing First in Baudh Darshan at the Acharya Examination 2012. 9. B.H.U. Medal Awarded to Shri Paras Mani sharma for standing First in Veda at the Acharya Examination 2012. 10. B.H.U. Medal Awarded to Shri Krishna Nand Singh for standing First in Dharmagam at the Acharya Exam.,2012. SILVER MEDAL 11. Raj Kishore Kapoor Silver Medal Awarded to Shri Manish Tiwari for standing First in Jyotish at the Acharya Examination 2012. -

The White Ribbon Campaign

The White Ribbon Campaign Mapping of tools for working with men and boys to end violence against girls, boys and women The White Ribbon Campaign Save the Children fights for children’s rights. We deliver immediate and lasting improvements to children’s lives worldwide. Save the Children works for: ● a world which respects and values each child ● a world which listens to children and learns ● a world where all children have hope and opportunity ISBN 99946-2-152-1 © 2006 Save the Children Sweden – South and Central Asia Region and UNIFEM Regional Office for South Asia This publication is protected by copyright. It may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For use in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher. Concept: Lena Karlsson, Ravi Karkara and Nandita Baruah Report by: Syed Saghir Bukhari and Ravi Karkara Reviewed by: Archana Tamang, Gary Barker and Lena Karlsson Production: Neha Bhandari, Savita Malla and Prajwol Malekoo Copy edit: Maya Shanker Images: MASVAW, India; Save the Children Canada, Asia Regional Office; Save the Children Sweden, Regional Office for South and Central Asia; Save the Children Sweden-Denmark, Bangladesh; Save the Children Sweden-Norway, Afghanistan; Save the Children UK, Afghanistan. Design and printing: Print Point Publishing (3P), Tripureshwor, Kathmandu Published by: Save the Children Sweden UNIFEM Regional Office for South and Central Asia Regional Office for South Asia Sanepa Road, Kupundole, Lalitpur 223 Jor Bagh, Lodhi Road GPO 5850, Kathmandu, Nepal New Delhi - 110003, India Tel: +977-1-5531928/9 Tel/Fax: +91-11-469-8297 Fax: +977-1-5527266 www.unifem.org.in [email protected] [email protected] www.rb.se Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................ -

S.No Name Program App ID Date Time 1 SHIVAM SHARMA B.VOC

S.No Name Program App ID Date Time 1 SHIVAM SHARMA B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S100032" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 2 SHIVANI SHAKYA B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S101663" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 3 DEEKSHA VIKRAM SINGH B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S101680" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 4 ANMOL KHANDELWAL B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S101703" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 5 TUSHAR BANSAL B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S101758" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 6 AKRATI PACHAURI B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S101847" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 7 LUVI SHARMA B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S102541" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 8 TANUSHKA RAGHUVANSHI B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S102543" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 9 VANSHITA PARMAR B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S102547" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 10 SAUMYA GUPTA B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S102660" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 11 SUMIT SONI B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S102720" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 12 ESHA PHULWANI B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S102727" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 13 NISHA B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S102964" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 14 TANYA DWIVEDI B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S102969" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 15 SANCHIT PACHAURI B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S103128" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 16 PRERNA GUPTA B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S103130" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 17 TUSHAR BANSAL B.VOC. (NON SCIENCE GROUP) "2S103263" 2nd August 2020 06:00 AM 18 SAGAR UPADHYAY B.VOC. -

Campus Beats Love Is a Sudden Uprising in The

Love just happens. Nobody thinks about how to love, or when and where to love. Campus Beats Love is a sudden uprising in the heart. There is no logic in this. It is beyond logic. Published By Amrita School Of Communication, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham AMMA Thursday ,Octobar 17, 2008 Ettimadai, Coimbatore - 641105, email:[email protected], Ph: 91422-2656422, www.amrita.edu 150 cases after ban on public Doctor or Engineer...? smoking Children of Ettimadai village strive to realize their dreams with the help of Ms.Shobana Madhavan and Amrita students Arya TG, Meenakshi Nautiyal & Ananth N Reporters After the Act on Prohibition of Smoking & Spitting, 2003 passed by Tamil Nadu Government was re-enforced from 2nd October, 2008, the number of cases booked in Coimbatore are 150. There is no special com- mittee being formed to check the smoking in public places. The local police themselves can see whether Eagerly looking forward to a bright future...children attending the classes conducted by Amrita students the law is implemented or current infrastructure and the School Of Business and Amrita like these children”. And engi- obeyed. So far the offenders Nishanth.M V syllabus in the schools here, one School of Engineering under the neering students, Surendhar and are fined Rs.200/- for the Reporter cannot help but wonder whether university are today playing a Nivedita add together, “It’s first time and second time is Nine year old Karthik dreams Karthik, Surendar, Muthukumar very important role towards wonderful to be with these chil- Rs. 500/- third time offense of becoming a police and scores of students like them helping these children realise dren and help them in what ever can lead to jail imprison- Commissioner when he grows would ever realize their dreams! their dreams. -

Okka Magadu Movie Full Hd Video Download

Okka Magadu Movie Full Hd Video Download 1 / 4 Okka Magadu Movie Full Hd Video Download 2 / 4 3 / 4 This song is composed by mani sharma. Okka Magaadu (telugu) film stars bala krishna, nisha kothari, simran,the songs were released in Dec 23, · Telugu Lyrics .... Okka Magadu 2 Full Movie In Hd 720p Download Okka Magadu 2 ... Aaa Ee Eee Video Song . tamil hd video songs download. 1080p movie Raat Gayi, .. Check out Okka Magadu by Rita, Bhargavi on Amazon Music. Stream ... From the Album Okka Magadu (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) ... Buy song $1.29.. Okka Magadu HD Video. Top DMCA | Contacts © 2018 SabHD.Net. sabhd.net wants to. Show notifications. sabhd.net wants to send you notifications. Allow. Download Aarakshan movie Full HD Video Songs. ... 1080p High Definition MP4 Blu-ray . in tamil download hd Okka Magadu full movie .. Okka .... Oka magadu mp3 songs; okka magadu movie songs free download; okkamagadu songs telugu songs download free; okka magadu song audio download; okka .... Okka magadu full movie part 8/14 balakrishna, simran, anushka sri balaji video youtube. Seethaiah movie okka magadu video song hari krishna soundarya simran .... Okka Magadu movie download Actors: Anushka Shetty Devadas Kanakala ... Download Okka Magadu Okka Magadu :: (2008) Biggest Disaster In TFI. ... Video Songs,Okka Magadu Song,Okka Magadu Bala Krishna Songs .... Anushka Shetty in Okka Magadu (2008) Okka Magadu (2008) ... Find out which Telugu movies got the highest ratings from IMDb users, from classics to recent .... Okka Magadu Full Movie Balakrishna, Simran, Anushka. Sri Balaji Video full video in hd 720p 1080p mp3 torrent mp4 free utorrent 3gp mkv Avi watch online. -

SC043 (GEOINFORMATICS/IT)] ADVERTISED AGAINST ADVERTISEMENT No

LIST OF SCREENED-OUT CANDIDATES WHO HAD APPLIED FOR THE POST OF SCIENTIST/ENGINEER 'SC' [SC043 (GEOINFORMATICS/IT)] ADVERTISED AGAINST ADVERTISEMENT No. NESAC/RMT-R/02/2019 DATED 24.01.2020. Sl. Reg. No. Name Reason for rejection NO. 1 202001517 BASOJU RAJESH Below the cut-off marks of merit list 2 202002076 ANISHA NARENDRAN Below the cut-off marks of merit list 3 202001612 GOPI P Below the cut-off marks of merit list 4 202001758 DEEPAK P M Below the cut-off marks of merit list 5 202001289 ANKITA SAXENA Below the cut-off marks of merit list 6 202001845 MADHAVI SUPRIYA VENIGALLA Below the cut-off marks of merit list 7 202002058 VINJAMURI V S A P M KAMESWARA Below the cut-off marks of merit list SARMA 8 202001836 G ARUN Below the cut-off marks of merit list 9 202001827 ROHIT MANGLA Below the cut-off marks of merit list 10 202001956 MANI SHARMA Below the cut-off marks of merit list 11 202001487 RESMI K S Below the cut-off marks of merit list 12 202002097 RITESH MUJAWDIYA Below the cut-off marks of merit list 13 202001890 NEERAJA KOLIPE Below the cut-off marks of merit list 14 202001280 ARTI TIWARI Below the cut-off marks of merit list 15 202001454 PRANAV SURESH SHINGANE Below the cut-off marks of merit list 16 202001930 DEVANSHI VARSHNEY Below the cut-off marks of merit list 17 202001872 NAVEEN R Below the cut-off marks of merit list 18 202002073 KAVACH MISHRA Below the cut-off marks of merit list 19 202002085 G SAI VENKAT Below the cut-off marks of merit list 20 202001349 AKANSHA PATEL Below the cut-off marks of merit list 21 202001184 -

S. No. ID Full Name Father's Name State District 1 423232

S. No. ID Full Name Father's Name State District 1 423232 AKrishnavamshi Amineni Ravi Chandra Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 2 425654 B ASHOK B Thirupalu Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 3 421719 Bisathi Bharath B Adinarayana Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 4 428717 Jakkalavadiki chikkanna Jakkalavadiki ganganna Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 5 423785 jeevan Kumar B. Bharath Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 6 426534 Johar babu P BHEEMAPPA Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 7 425588 K NAGENDRA PRASAD KADAVAKOLANU NAGANNA Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 8 436056 Kallamadi Navitha Kallamadi Nagalinga Reddy Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 9 424985 Keerthana pavagada Madhusudhana char pavagada Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 10 423351 KORRA REDYA NAIK K.kristaiah naik Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 11 423539 Lokesh B.kondaiah Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 12 422760 Maddy Siva charan M Vijay Kumar Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 13 422565 Malkar Namratha Rao Malkar Ravichandra Rao Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 14 424032 Mamilla Ganesh Mamilla Narayana Swamy Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 15 425956 Mohammad Subahan V Fakroddin V Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 16 428097 NAGARI NAVEEN KUMAR NAGARI THIPPANNA Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 17 421729 NAWAB MEHETAB NASREEN N NAZEER AHMED Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 18 424602 Pallepothula sateesh kumar B.jeevan kumar Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 19 426288 Pedda Yammanuru Sudhakar P.Y.Sudhakar Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 20 422282 Rohith Vasantham Vasantham Madhusudhan Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 21 428633 Sake saisushma S. Narayana swamy Andhra Pradesh Anantapur 22 426347 Sashipreetham M. Radhakrishna Andhra Pradesh -

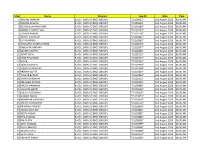

Consolidated Data on Commission and Expenses Paid to Distributors During FY 2019-20 and Additional Disclosures

Consolidated data on Commission and Expenses paid to Distributors during FY 2019-20 and additional disclosures All figures - Rs. in Lacs Sr. No. Name of the ARN Holder Gross Amount paid Gross Inflows Net Inflows Averge Assets Ratio of AUM to under Gross inflows Management for FY 2019-20 1 3I WEALTH ADVISORS LLP 142.51 53,972.21 -10,283.73 21,424.59 0.27 2 3Q FINANCIAL CONSULTANTS LLP 91.82 11,015.66 931.85 15,024.33 1.15 3 5AB ENTERPRISES 66.00 35,181.37 3,118.60 13,149.28 0.36 4 6TH SENSE INVESTMENTS CONSULTANTS 107.25 2,723.20 440.54 9,837.89 2.96 5 A K Narayan 113.67 1,140.33 -1,991.21 17,201.72 11.56 6 A R J Financial Consultants India Private Limited 121.52 3,509.06 946.76 9,990.21 2.34 7 A.G. Financial Services 272.10 14,981.82 9.30 39,007.92 2.40 8 AADI WEALTH MANAGEMENT (P) LTD. 299.51 25,604.09 -34,545.97 33,779.98 0.53 9 Aadinath Investment 214.03 29,667.68 -5,294.32 23,394.68 0.71 10 Aahlada Securities Pvt Ltd 139.23 3,894.59 743.27 19,224.05 3.89 11 Aalps Investment Advisory 385.98 48,170.19 2,316.08 52,185.25 1.05 12 Abacus Corporation Private Limited 830.12 2,763.10 -12,812.87 87,213.40 22.33 13 ABACUS MUTUAL 136.98 36,883.52 21,753.22 12,686.38 0.49 14 Abchlor Investment Advisors (P) Ltd 394.35 21,837.94 1,618.63 36,490.99 1.53 15 Abhenav Khettry 132.94 13,079.10 1,044.66 13,578.97 1.02 16 Abhimanyu Kantilal Sharma 98.02 20,445.51 3,624.32 16,302.51 0.77 17 Abhinav Mehta 122.61 9,234.13 2,581.10 14,194.75 1.34 18 Abhishek Sunil Gupta 143.33 8,349.74 1,632.89 17,294.04 1.93 19 Abira Management Services Ltd 15.53 1,692.74 9.08 5,797.90 2.79 20 Abm Investment 92.48 3,594.03 909.17 12,373.25 2.99 21 ABSOLUTE GROWTH 131.57 3,777.25 2,668.42 11,794.91 2.57 22 ACCELYST SOLUTIONS PRIVATE LIMITED 1.01 813.96 -248.02 543.45 0.42 23 ACCORD FINANCIAL SERVICES LLP 211.07 8,580.07 -124.15 17,804.45 1.64 24 ACE CAPITAL ADVISORS 23.47 2,804.67 -958.55 14,738.83 5.21 25 ACE FNSUPERMARKET PVT. -

Jorethang Sr Sec Schoo

STATE OF SIKKIM MUNICIPAL ELECTORAL ROLL - 2021 AC No.& Name: 08-SALGHARI-ZOOM(SC) Municipality No. & Name: 5-NAYABAZAR JORETHANG NAGAR PANCHAYAT Ward No & Name: 2-TRIKALESHWAR Polling Station No. & Name: S/5/2/1-JORETHANG SR. SEC. SCHOOL ROOM NO.II Total Voters : Male: 425 Female: 321 Total: 746 N 1 EPIC NO. :BFM0148122 N 2 EPIC NO. :WLY0037887 N 3 EPIC NO. :CDJ0167973 Name : SANDEEP PRADHAN Father's Name : KAMAL Name : DIPIKA KUMARI Name : MD. JABBAR ALAM PRADHAN Father's Name : LALAN SHAH Father's Name : MD. IDRIS Age : 31 Gender: M Age : 27 Gender: F Age : 45 Gender: M N 4 EPIC NO. :WLY0025668 N 5 EPIC NO. :WLY0041558 N 6 EPIC NO. :CDJ0167213 Name : RUBEN GURUNG Name : PEDENLA BHUTIA Name : PUNAM GUPTA Father's Name : JAS BDR. Mother's Name : MAMTA BHUTIA Husband's Name : AJAY GUPTA GURUNG Age : 39 Gender: F Age : 27 Gender: F Age : 55 Gender: M N 7 EPIC NO. :WLY0044537 N 8 EPIC NO. :WLY0056176 N 9 EPIC NO. :CDJ0168443 Name : JYOTI KUMARI Name : PURNA KUMARI LOHAR Husband's Name : MANISH Father's Name : BHAKTA Name : M.D NAZIR RAWAT BAHADUR LOHAR Father's Name : M.D TAHID Age : 35 Gender: F Age : 31 Gender: F Age : 44 Gender: M N 10 EPIC NO. :WLY0038109 N 11 EPIC NO. :WLY0004028 N 12 EPIC NO. :WLY0034066 Name : MANU RAI Name : BINITA RAI Name : ANIL PRASAD Father's Name : LT.BHIM KUMAR Husband's Name : CHANDRA Father's Name : ASHOK PRASAD RAI DIWAS RAI Age : 26 Gender: M Age : 41 Gender: M Age : 34 Gender: F N 13 EPIC NO.