This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesfic-Eclectic.Pdf

LesFic Eclectic VOLUME ONE Edited by Robyn Nyx 2019 LesFic Eclectic VOLUME ONE Edited by Robyn Nyx 2019 LesFic Eclectic © 2019 by LesFic Collective. All rights reserved. First edition: September 2019 Credits Editor: Robyn Nyx Production design: Robyn Nyx Cover design by Robyn Nyx This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors’ imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locals is entirely coincidental. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission. This eBook is transferable (which is not usually the case). However, this eBook cannot be sold on as it is an infringement on the copyright of this work. Dedication To all you lovely readers who support, read, and breathe LesFic And to all you wonderful authors who cry blood and make magic Thank you, Robyn Nyx Reviews for the Author’s Works Lise Gold French Summer A perfect book for reading while lying on a sun lounger in your own back yard or by a pool somewhere warm and sunny, or equally for a cold winter’s day when you need to be metaphorically transported to a place just like that! Curve magazine Lily’s Fire All in all this was a lot of fun to read! Emotional, well put together and written, and very exciting. I highly recommend giving this romance a read. LesBiReviewed Jeannie Levig A Wish Upon a Star A perfect book if you’re looking for something a little different from the usual romance fare. -

Your Career Guide

ROYAL NAVAL RESERVE Your career guide YOUR ROLE | THE PEOPLE YOU’LL MEET | THE PLACES YOU’LL GO WELCOME For most people, the demands of a job and family life are enough. However, some have ambitions that go beyond the everyday. You may be one of them. In which case, you’re exactly the kind of person we’re looking for in the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR). The Royal Naval Reserve is a part-time force of civilian volunteers, who provide the Royal Navy with the additional trained people it needs at times of tension, humanitarian crisis, or conflict. As a Reservist, you’ll have to meet the same fitness and academic requirements, wear the same uniform, do much of the same training and, when needed, be deployed in the same places and situations as the regulars. Plus, you’ll be paid for the training and active service that you do. Serving with the Royal Naval Reserve is a unique way of life that attracts people from all backgrounds. For some, it’s a stepping stone to a Royal Navy career; for others, a chance to develop skills, knowledge and personal qualities that will help them in their civilian work. Many join simply because they want to be part of the Royal Navy but know they can’t commit to joining full-time. Taking on a vital military role alongside your existing family and work commitments requires a great deal of dedication, energy and enthusiasm. In return, we offer fantastic opportunities for adventure, travel, personal development and friendships that can last a lifetime. -

Kiwi Unit Manual 2012

RE-ENACTMENT MANUAL OF ELEMENTARY TRAINING 2nd N.Z.E.F. 1939-1945 N.Z. SECTION W.W.2 Historical Re-enactment Society 2O12 1 CONTENTS 2. INTRODUCTION 3. STANDING ORDERS 4. TRAINING SCHEDULE 6. STANDING ORDERS OF DRESS AND ARMS 7. UNIFORM AND INSIGNIA 8. SECTION UNIFORM REQUIREMENTS 9. SERVICE DRESS AND KHAKI DRILL 10. BATTLE DRESS UNIFORM 11. UNIFORMS AND HEADGEAR 12. UNIFORMS AND HEADGEAR 13. UNIFORMS OF NZ FORCES 14. UNIFORMS OF NZ FORCES (PACIFIC) 15. QUARTERMASTERS STORES 16. INSIGNIA 17. RANK 18. COLOUR INSIGNIA 19. FREYBURG AND THE DIVISION 20. COMMAND ORGANISATION 21. BRIGADE LAYOUT 22. COMMUNICATIONS PHOTO BY CLIFF TUCKEY/ KEVIN CARBERRY 23. THE EVOLUTION OF COMMONWEALTH TACTICS 24. THE EVOLUTION OF COMMONWEALTH TACTICS 25. SMALL UNIT TACTICS 26. BATTLE TECHNIQUES 27. CASUALTY EVACUATION 28. CASUALTY EVACUATION 29. MILITARY PROTOCOL 30. FOOT DRILL 31. ARMS DRILL 32. ARMS DRILL (BAYONETS) 33. S.M.L.E. RIFLE 34. BREN GUN, THOMPSON SMG, VICKERS 35. BAYONET, REVOLVERS, STEN GUN, BROWNING MMG 36. ORDANANCE AND SUPPORT WEAPONS 37. ARTILLERY 38. VEHICLES 39. BREN CARRIERS 40. 37 PAT WEBBING 41. 37 PAT WEBBING 42. EXTRA KIT 43. RATIONS AND SMALL PACK 44. NEW ZEALANDS WAR EFFORT- CHARTS AND TABLES 45. GETTING IT RIGHT –SOME COMMON CONFUSIONS 46. CARING FOR KIT 47. GLOSSARY 48. GLOSSARY 49. BIBLOGRAPHY 50. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 2 WORLD WAR II HISTORICAL RE-ENACTMENT SOCIETY NEW ZEALAND TRAINING & REFERENCE MANUAL AN INTRODUCTION. At first glance the New Zealand soldier in the Second World War resembled any Commonwealth soldier. From a distance of 20 yards they looked no different from Australian, Canadian, or British troops unless they happened to be wearing their 'lemon squeezers'. -

Requirement of Clothing/Uniform Items For

REQUIREMENT OF CLOTHING/UNIFORM ITEMS FOR THE YEAR 2017 - 2018 Annexure-I SB SCRB/C SP SP SP Ri- SP SP SP SP SP SP SP SB (Dic, Total Slno Items 1MLP 2MLP 3MLP 4MLP 5MLP 6MLP SF-10 SP WJH MPRO F&ES PTS SB (SECURITY PHQ ID/ EKH WKH Bhoi WGH EGH SGH SWKH NGH EJH SWGH Anti-Infil) Qty. WING) ACB 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 1 Ammunition Pouch. 500 900 89 100 1589 Nos. Badge - Cap Badge 2 (MLP/1MLP/2MLP/3MLP/4MLP/5MLP/6MLP/MPRO/ 104 1464 1300 100 400 50 100 100 3618 Nos. MFES/SF-10) Badge - Title Shoulder Badge 3 (MLP/1ML/2MLP/3MLP/4MLP/5MLP/6MLP/MPRO/MFES/ 2600 3000 40 400 100 50 6190 Pair SF-10 4 Belt - Black leather for MFES/Traffic. 100 35 40 175 Nos. 5 Belt - Brown Leather Cross Belt with Buckles 100 200 11 5 10 4 330 Nos. 6 Belt - Brown Leather for ASI/Hav/Const with Buckles 22 50 400 80 552 Nos. 7 Belt - Brown Leather for officers with Buckles 200 60 25 60 345 Nos. 8 Belt - Black Belt Nylon 500 150 600 1000 2250 Nos. 9 Beret Cap - Wollen Black 900 2800 3700 Nos. 10 Beret Cap - Wollen Red. 35 35 Nos. 11 Beret Cap - Woollen Green 3200 245 180 490 200 40 50 70 55 146 6 4682 Nos. 12 Beret Cap - Woollen Khaki 1044 1000 600 700 202 150 530 50 200 145 60 65 60 92 32 4930 Nos. -

Volunteer Reserve Forces

OFFICIAL Volunteer Reserve Forces Contents Policy Statement ........................................................................................................................ 2 Principles .................................................................................................................................... 2 Responsibilities .......................................................................................................................... 6 Individuals ...................................................................................................................... 6 First Line Managers ........................................................................................................ 7 Second Line Managers ................................................................................................... 7 Senior Leadership Team (SLT) ........................................................................................ 7 People Directorate ......................................................................................................... 8 Chief Officer Team ......................................................................................................... 8 Additional Information .............................................................................................................. 9 OFFICIAL Volunteer Reserve Forces Page 1 of 9 OFFICIAL Policy Statement 0BSummary West Yorkshire Police (WYP) supports the Volunteer Reserve Forces (VRF), which is made up of men and women who train -

Sunset for the Royal Marines? the Royal Marines and UK Amphibious Capability

House of Commons Defence Committee Sunset for the Royal Marines? The Royal Marines and UK amphibious capability Third Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 30 January 2018 HC 622 Published on 4 February 2018 by authority of the House of Commons The Defence Committee The Defence Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Defence and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Dr Julian Lewis MP (Conservative, New Forest East) (Chair) Leo Docherty MP (Conservative, Aldershot) Martin Docherty-Hughes MP (Scottish National Party, West Dunbartonshire) Rt Hon Mark Francois MP (Conservative, Rayleigh and Wickford) Graham P Jones MP (Labour, Hyndburn) Johnny Mercer MP (Conservative, Plymouth, Moor View) Mrs Madeleine Moon MP (Labour, Bridgend) Gavin Robinson MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Belfast East) Ruth Smeeth MP (Labour, Stoke-on-Trent North) Rt Hon John Spellar MP (Labour, Warley) Phil Wilson MP (Labour, Sedgefield) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/defcom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry page of the Committee’s website. Committee staff Mark Etherton (Clerk), Dr Adam Evans (Second Clerk), Martin Chong, David Nicholas, Eleanor Scarnell, and Ian Thomson (Committee Specialists), Sarah Williams (Senior Committee Assistant), and Carolyn Bowes and Arvind Gunnoo (Committee Assistants). -

Force Policy

NOT PROTECTIVELEY MARKED Volunteer Reserve Forces Contents Policy Statement ........................................................................................................................ 2 Principles .................................................................................................................................... 2 Responsibilities .......................................................................................................................... 6 Individuals ...................................................................................................................... 6 First Line Managers ........................................................................................................ 7 Second Line Managers ................................................................................................... 7 Senior Leadership Team (SLT) ........................................................................................ 7 Human Resources Department...................................................................................... 8 Chief Officer Team ......................................................................................................... 8 Additional Information .............................................................................................................. 9 NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Volunteer Reserve Forces Page 1 of 9 NOT PROTECTIVELEY MARKED Policy Statement Summary West Yorkshire Police (WYP) supports the Volunteer Reserve Forces (VRF), which is -

Royal Marines Reserve and the Career Opportunities the Royal Navy You’Re Probably Available to You

YOUR ROLE THE PEOPLE YOU’LL MEET THE PLACES YOU’LL GO RESERVE CAREERSMARINES R OYAL WELCOME For most people, the demands of one job are enough. However, some of you need more of a challenge, and they don’t come much bigger than joining the Royal Marines Reserve. The Royal Marines Reserve is a part-time force of civilian volunteers, who give the Royal Marines extra manpower in times of peace and humanitarian crisis or war. You’ll be trained to the same standards as the regular Royal Marines, have to pass the same commando tests and, of course, wear the same coveted green beret. The obvious difference is that, as a Reservist, you combine service as a fully-trained Commando with your civilian career. It’s a unique way of life that attracts people from all backgrounds. But, the nature of commando training and service means we can’t just take anybody who fancies a challenge. We, and you, have to be absolutely sure it’s the right thing for you and that you’re physically and mentally up to the job. It’s a long, tough road to the green beret. But if you like the idea of travel, sport, adventure and, most importantly, the satisfaction of completing the world’s toughest military training and getting paid for it, this is where it begins. We wish you every success and look forward to welcoming you to the Royal Marines Reserve. Visit royalmarines.mod.uk/rmr or call 08456 00 14 14 CONTENTS Welcome 2 Who we are and what we do 4 What it means to be a Reservist 8 Joining, training and 10 specialisations General Duties Marines and Officers How to join Commando training Commando specialisations Commando Officer specialisations Royal Marines Reserve life 24 Your commitment What we can offer you Sports and recreation And finally.. -

Armed Forces Act 1981 CHAPTER 55 ARRANGEMENT of SECTIONS PART I

Armed Forces Act 1981 CHAPTER 55 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I CONTINUANCE OF SERVICES ACTS Section 1. Continuance of Services Acts. PART II TRIAL AND PUNISHMENT OF OFFENCES 2. Young service offenders: custodial orders. 3. Power to stay further proceedings under one of the Services Acts with a view to other proceedings. 4. Marines : forfeiture of service where desertion confessed. 5. Power on review or confirmation to annul the taking into consideration of other offences. 6. Trial of persons ceasing to be subject to service law and time limits for trials. 7. Extent of accused's right to copy of record of court-martial proceedings. 8. Right of penalised parent or guardian to copy of record of court-martial proceedings. 9. Evidence derived from computer records. 10. Amendments relating to trial and punishment of civilians under the Services Acts. 11. Minor amendments and repeals relating to procedure and evidence. 12. Increase in fine for certain minor offences under the Reserve Forces Act 1980. PART III MISCELLANEOUS New powers in relation to persons under incapacity 13. Temporary removal to and detention for treatment in service hospitals abroad of servicemen and others suffering from mental disorder. A ii c. 55 Armed Forces Act 1981 Section 14. Temporary removal to and detention in a place of safety abroad of children of service families in need of care or control. Amendments of the Naval Discipline Act 1957 as to offences and punishments 15. Prize offence: minor amendment as to intent. 16. Power on summary trial to award stoppages. 17. Abolition of death penalty for spying in ships etc. -

Gendered Divisions of Military Labour in the British Armed Forces

Edinburgh Research Explorer Gendered divisions of military labour in the British armed forces Citation for published version: Woodward, R & Duncanson, C 2016, 'Gendered divisions of military labour in the British armed forces', Defence Studies, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 205-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2016.1180958 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/14702436.2016.1180958 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Defence Studies Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Defence Studies on 9 May 2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/14702436.2016.1180958 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Gendered divisions of military labour in the British armed forces. Rachel Woodward and Claire Duncanson Accepted by Defence Studies 18th April 2016. Version for Newcastle University e-prints Abstract This paper examines statistical data on the employment of women in the British armed forces. -

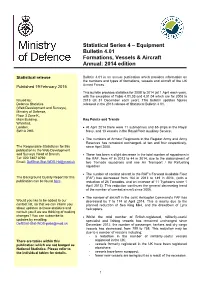

MOD Formations, Vessels and Aircraft Report: 2014

Statistical Series 4 – Equipment Bulletin 4.01 Formations, Vessels & Aircraft Annual: 2014 edition Statistical release Bulletin 4.01 is an annual publication which provides information on the numbers and types of formations, vessels and aircraft of the UK Armed Forces. Published 19 February 2015 This bulletin provides statistics for 2008 to 2014 (at 1 April each year), with the exception of Table 4.01.03 and 4.01.04 which are for 2008 to Issued by: 2013 (at 31 December each year). This bulletin updates figures Defence Statistics released in the 2013 release of Statistical Bulletin 4.01. (Web Development and Surveys), Ministry of Defence, Floor 3 Zone K, Main Building, Key Points and Trends Whitehall, London, At April 2014 there were 11 submarines and 65 ships in the Royal SW1A 2HB. Navy, and 13 vessels in the Royal Fleet Auxiliary Service. The numbers of Armour Regiments in the Regular Army and Army Reserves has remained unchanged, at ten and four respectively, The Responsible Statistician for this since April 2000. publication is the Web Development and Surveys Head of Branch. There has been a slight decrease in the total number of squadrons in Tel: 020 7807 8792 the RAF, from 47 in 2013 to 44 in 2014, due to the disbandment of Email: [email protected] two Tornado squadrons and one Air Transport / Air Refuelling squadron. The number of combat aircraft in the RAF’s Forward Available Fleet The Background Quality Report for this (FAF) has decreased from 164 in 2013 to 149 in 2014, (with a publication can be found here. -

The Queen's Regulations for the Royal Navy

BRd 2 Issue Date April 2014 Superseding BRd 2 Dated April 2013 BRd 2 THE QUEEN’S REGULATIONS FOR THE ROYAL NAVY This document is the property of Her Britannic Majesty's Government. The text in this document (excluding the department logos) may be reproduced for use by Government employees for Ministry of Defence business, providing it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. Crown copyright material may not be used or reproduced for any other purpose without first obtaining permission from DIPR, MOD Abbey Wood, Bristol, BS34 8JH. This permission will be in the form of a copyright licence and may require the payment of a licence fee. By Command of the Defence Council Fleet Commander and Deputy Chief of Naval Staff i April 2014 BRd 2 SPONSOR INFORMATION This publication is sponsored by the Fleet Commander & Deputy Chief of Naval Staff. All correspondence concerning this publication is to be sent to: CNLS L3 Casework MP 4-2 Henry Leach Building Whale Island PORTSMOUTH Hants PO2 8BY This publication is published by Navy Publications and Graphics Organisation (NPGO) Navy Author 09 Navy Publications and Graphics Organisation Pepys Building HMS COLLINGWOOD Fareham Hants PO14 1AS © UK MOD Crown Copyright 2014 ii April 2014 BRd 2 RECORD OF CONFIGURATION CONTROL Authored by Checked by Approved by Edition/Change: Name: Name: Name: 2011 D Dawe D Dawe D Dawe Tally: Tally: Tally: DS Law L&C Admin DS Law L&C Admin DS Law L&C Admin Date of edition/change: Signature: Signature: Signature: Signed on File Copy Signed on File Copy Signed