Allen Nicholas, Supervisor, Shawnee National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

2017 - Year in Review Annual Report of Land Conservation Achievements in Illinois

2017 - Year in Review Annual Report of Land Conservation Achievements in Illinois Written by David Holman The author thanks PSCC for their ongoing encouragement and support in the writing of this annual report. While the work and partnership of PSCC greatly contributes to the foundation of this writing, please note that the facts, figures, opinions, and general musings in this report are that of the author, and not of PSCC. About Prairie State Conservation Coalition Prairie State Conservation Coalition is a statewide, not-for-profit association that works to strengthen the effectiveness of conservation land trusts in Illinois. Conservation land trusts, such as local land conservancies, are also not-for-profit organizations seeking to improve the quality of life in their communities. Collectively, these organizations have helped protect more than 200,000 acres of open space in Illinois. PSCC provides continuing education and training for conservation land trusts and advocates for strong statewide policies that benefit land conservation. Find out more at prairiestateconservation.org. Author bio David Holman, the author of this report, is an independent conservation professional who works closely with the Prairie State Conservation Coalition and the individual land trust members of PSCC, as well as local, state, and federal agencies devoted to conservation. He specializes in Geographic Information Systems mapping, organizational efficiency, authoring Baseline and Current Conditions reports, irreverence, and project development, and is the creator of Illinois’ Protected Natural Lands Database and accompanying I-View interactive mapping application. He can be reached at [email protected]. 2017 - Year in Review A long and memorable year soon will withdraw to the pages of what undoubtedly will be a wild history. -

1 Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Minutes of the 206

Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Minutes of the 206th Meeting (Approved at the 207th Meeting) Burpee Museum of Natural History 737 North Main Street Rockford, IL 61103 Tuesday, September 21, 2010 206-1) Call to Order, Roll Call, and Introduction of Attendees At 10:05 a.m., pursuant to the Call to Order of Chair Riddell, the meeting began. Deborah Stone read the roll call. Members present: George Covington, Donnie Dann, Ronald Flemal, Richard Keating, William McClain, Jill Riddell, and Lauren Rosenthal. Members absent: Mare Payne and David Thomas. Chair Riddell stated that the Governor has appointed the following Commissioners: George M. Covington (replacing Harry Drucker), Donald (Donnie) R. Dann (replacing Bruce Ross- Shannon), William E. McClain (replacing Jill Allread), and Dr. David L. Thomas (replacing John Schwegman). It was moved by Rosenthal, seconded by Flemal, and carried that the following resolution be approved: The Illinois Nature Preserves Commission wishes to recognize the contributions of Jill Allread during her tenure as a Commissioner from 2000 to 2010. Jill served with distinction as Chair of the Commission from 2002 to 2004. She will be remembered for her clear sense of direction, her problem solving abilities, and her leadership in taking the Commission’s message to the broader public. Her years of service with the Commission and her continuing commitment to and advocacy for the Commission will always be greatly appreciated. (Resolution 2089) It was moved by Rosenthal, seconded by Flemal, and carried that the following resolution be approved: The Illinois Nature Preserves Commission wishes to recognize the contributions of Harry Drucker during his tenure as a Commissioner from 2001 to 2010. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement Appendices

This document can be accessed on the Shawnee National Forest website: www.fs.fed.us/r9/forests/shawnee. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Shawnee National Forest Forest Plan FEIS Appendix A – Forest Plan Revision Issues and Public Involvement APPENDIX A FOREST PLAN REVISION ISSUES AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT I. INTRODUCTION The first SNF Land and Resource Management Plan (Plan) was approved on November 24, 1986. In 1988, following 23 administrative appeals, the Forest met with appellants and reached a settlement agreement. Significant changes in the Plan resulted in an amended Forest Plan signed in 1992. A lawsuit on nine counts was filed against the Plan in 1994. The court ruled in favor of the Forest Service on five counts and in favor of the plaintiffs on four. The court remanded the entire Plan, but allowed implementation, enjoining specific activities, including commercial, hardwood-timber harvest, ATV trail designation and oil and gas development. -

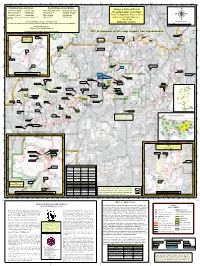

25% of Proceeds of This Map Support Trail Improvements Hiker Only 001E 88°42'30"W 88°42'0"W 88°41'30"W 88°41'0"W UPPER 467 SPRING RD CENTER Hitching Post TH 001 UPPER

88°43'0"W 88°42'0"W 88°41'0"W 88°40'0"W 88°39'0"W 88°38'0"W 88°37'0"W 88°36'0"W 88°35'0"W 88°34'0"W 88°33'0"W 88°32'0"W 88°31'0"W 88°30'0"W 88°29'0"W 88°28'0"W 88°27'0"W 88°26'0"W 88°25'0"W 020 37°38'0"N Emergency Contact Information National Forest Contact Numbers Shawnee National Forest Gallatin County Sheriff (618) 269-3137 Hidden Springs Ranger District Forest Supervisor’s Office GARDEN Hardin County Sheriff (618) 287-2271 602 N. First Street 50 Highway 145 South Hiker/Equestrian Trails Map Eagle Creek OF THE Pope County Sheriff (618) 683-4321 Route 45 North Harrisburg, IL 62946 Water s he d 462 Trails Designation Project Area 37°37'0"N Saline County Sheriff (618) 252-8661 Vienna, IL 62995 (618) 253-7114 Emergency cellphone service may not be available in all (618) 658-2111 (800) 699-6637 Lusk Creek and Upper Bay Creek STATE map areas Watersheds 37°37'0"N 465 408 : 464 HIGHWAY 34 Contour017 interval = 20 feet Trail Conditions Hotline 618-658-1312 463 Jackson Hollow Eddyville Vicinity 0 0.5 1 2 To report trail conditions and obtain updated information regarding wet -weather closures in the Lusk Creek Wilderness 460 408 460 Miles HORTON HILL RD 465 WWW.SNFFRIENDS.ORG Hiker Only 460 37°36'0"N [email protected] GARDEN OF THE GODS WILDERNESS Hiker Only Shawnee National Forest website: www.fs.usda.gov/shawnee 37°36'0"N 25% of proceeds of this map support trail improvements Hiker Only 001E 88°42'30"W 88°42'0"W 88°41'30"W 88°41'0"W UPPER 467 SPRING RD CENTER Hitching Post TH 001 UPPER SPRINGS RD GARDEN OF THE GODS WILDERNESS Jackson -

The Hoosier- Shawnee Ecological Assessment Area

United States Department of Agriculture The Hoosier- Forest Service Shawnee Ecological North Central Assessment Research Station General Frank R. Thompson, III, Editor Technical Report NC-244 Thompson, Frank R., III, ed 2004. The Hoosier-Shawnee Ecological Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-244. St. Paul, MN: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Research Station. 267 p. This report is a scientific assessment of the characteristic composition, structure, and processes of ecosystems in the southern one-third of Illinois and Indiana and a small part of western Kentucky. It includes chapters on ecological sections and soils, water resources, forest, plants and communities, aquatic animals, terrestrial animals, forest diseases and pests, and exotic animals. The information presented provides a context for land and resource management planning on the Hoosier and Shawnee National Forests. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Key Words: crayfish, current conditions, communities, exotics, fish, forests, Hoosier National Forest, mussels, plants, Shawnee National Forest, soils, water resources, wildlife. Cover photograph: Camel Rock in Garden of the Gods Recreation Area, with Shawnee Hills and Garden of the Gods Wilderness in the back- ground, Shawnee National Forest, Illinois. Contents Preface....................................................................................................................... II North Central Research Station USDA Forest Service Acknowledgments ................................................................................................... -

Natural Resources Bruce Rauner, Governor One Natural Resources Way ∙ Springfield, Illinois 62702-1271 Wayne Rosenthal, Director

Illinois Department of Natural Resources Bruce Rauner, Governor One Natural Resources Way ∙ Springfield, Illinois 62702-1271 Wayne Rosenthal, Director www.dnr.illinois.gov FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Tim Schweizer September 27, 2018 217-785-4344 IDNR Announces State and Federal Sites Open for 2018 Youth Waterfowl Hunting Seasons Youth Hunt Weekends Precede Start of Regular Waterfowl Seasons in Each Zone SPRINGFIELD, IL – A number of Illinois state parks, fish and wildlife areas, conservation areas and recreation areas will be open to youth waterfowl hunting during the 2018 North Zone Youth Waterfowl Hunt, Central Zone Youth Waterfowl Hunt, South Central Zone Youth Waterfowl Hunt and South Zone Youth Waterfowl Hunt, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) announced today. Federal sites that fall under the IDNR waterfowl administrative rule that will be open are also listed below. At most sites, regulations that apply during the regular waterfowl hunting season apply during the Youth Hunt (hunters should check for site-specific regulations, including changes in legal shooting hours). During the Youth Hunt, the bag limits are the same as during regular seasons. As part of the Youth Hunt, hunters age 17 or younger may hunt ducks, geese, coots and mergansers, as long as they are accompanied by an adult at least 18 years of age. The accompanying adult cannot hunt these species, but may participate in other open seasons. Youth hunters must have a hunting license, Youth Hunting License, or Apprentice Hunting License. The youth hunter or her or his accompanying adult must have a valid FOID card. The supervising adult does not need to have a hunting license if they are not hunting other species. -

Regional Assessment of the Shawnee Hills Natural Division

Regional Assessment of the Shawnee Hills Natural Division Characteristics The Shawnee Hills Natural Division in the southern tip of Illinois is unglaciated hill country characterized by ridged uplands with many cliffs and deeply dissected valleys. Cuesta Ridge of the northern Shawnee Hills extends from the Mississippi River to the Ohio. The steep south facing escarpment is nearly in the middle of the division and separates the land to the north known as the Greater Shawnee Hills and the hills to the south which average 200 feet lower, known as the Lesser Shawnee Hills. Cave and sinkholes are locally common in the division. Presettlement vegetation was mostly forest with some prairie vegetation contained in glades and barrens. At present this natural division is the most heavily forested in the state and hosts some of the most outstanding biodiversity. Major Habitats & Challenges Forests - lack of oak regeneration; oak decline; potential infestation of European gypsy moth; overuse from recreation; land clearing and fragmentation for exurban development; invasion by Microstegium viminium could affect regeneration; other exotic plants (including Japanese and bush honeysuckle); lack of fire management leading to composition change; poorly planned logging continues to be a threat to healthy forests; overgrazing by livestock and abundant deer populations are affecting forest composition and destroying rare plants in some localities Open Woodland/Savanna/Barrens - lack of fire management leading to invasion by mesophytic species of trees and shrubs Grasslands - no large, contiguous natural grasslands exist; lack of diversity of species, succession and exotic plants (autumn olive, fescue, sericea lespedeza) are threats to Conservation Reserve Program and U.S. -

USDA Forest Service American Recovery and Reinvestment Act CIM Projects Facilities

USDA Forest Service American Recovery and Reinvestment Act CIM Projects Facilities FS ARRA CIM projects – FACILITIES ALASKA ......................................................................................................................... 4 ARIZONA........................................................................................................................ 5 CALIFORNIA ................................................................................................................ 12 COLORADO ................................................................................................................. 15 CONNECTICUT ............................................................................................................ 20 FLORIDA ...................................................................................................................... 21 GEORGIA ..................................................................................................................... 21 IDAHO...........................................................................................................................23 ILLINOIS ....................................................................................................................... 26 INDIANA ....................................................................................................................... 28 KENTUCKY .................................................................................................................. 28 MAINE...........................................................................................................................29 -

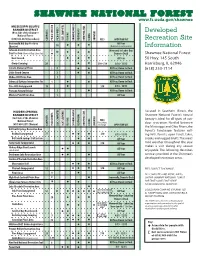

Shawnee National Forest R

SHAWNEE NATIONAL FOREST www.fs.usda.gov/shawnee R . TE MISSISSIPPI BLUFFS AT TER ST RANGER DISTRICT WA SHEL UNITS Developed West Side of the Shawnee AMPSITES National Forest C AMPSITES (618) 833-8576 (Jonesboro) C PICNIC PICNIC ELEC. FISHING DRINKING RESTROOMS DUMPING HIKING SHOWERS FEES OPEN FOR USE Recreation Site Buttermilk Hill Day Use Area � � � All Year (Boat-in) 10 (Restroom closed in winter) Information Johnson Creek Recreation Area 2 10 � � � Memorial to Labor Day Day Use Area (Memorial Day-Labor Day) � Dawn to Dusk Shawnee National Forest Boat Launch 1 � � � All Year 50 Hwy. 145 South Group Camping 20 � � $10 - $18 3/16 - 12/15 Harrisburg, IL 62946 Lincoln Memorial Picnic 1 8 � � All Year, Dawn to Dusk (618) 253-7114 Little Grand Canyon 2 � � All Year, Dawn to Dusk McGee Hill Picnic Area 1 All Year, Dawn to Dusk Oakwood Bottoms Interpretive Site 1 � � All Year, Dawn to Dusk Pine Hills Campground 13 � $10 3/16 - 12/15 Pomona Natural Bridge 1 � All Year, Dawn to Dusk Winters Pond Picnic Area 1 All Year R . Located in Southern Illinois, the TE HIDDEN SPRINGS AT ST WA RANGER DISTRICT PSITES Shawnee National Forest’s natural UNCHES M East Side of the Shawnee UNITS LA beauty is ideal for all types of out- CA FEES National Forest T Fees Subject door recreation. Nestled between AMPSITES (618) 658-2111 (Vienna) C PICNIC ELEC. BOA FISHING DRINKING RESTROOMS DUMPING HIKING SHOWERS to Change OPEN FOR USE the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, the Bell Smith Springs Recreation Area Forest’s landscape features roll- Redbud Campground 21 � � � $10 3/15 - 12/15 ing hills, forests, open lands, lakes, Bell Smith Springs Trail System � � All Year creeks, and rugged bluffs. -

WINTER 1996 Vol 12 (1) by John Schwegman, Illinois Native Plant Conservation Program Illinois Department of Conservation

ILLINOENSIS, WINTER 1996 Vol 12 (1) By John Schwegman, Illinois Native Plant Conservation Program Illinois Department of Conservation Comments While it is popular nowadays to say that technologically we are in or entering the information age, USDA weed scientist Randy Westbrooks points out that ecologically we are entering the homogenization age. Species that evolved on 5 separate continents are being transported by modern man and homogenized into a common worldwide biota. Continents that have been "engines of species evolution" since the breakup of Pangaea 185 million years ago are having their unique assemblages of co-evolved species invaded and disrupted by this homogenization. If we set back and let it happen, the result of this process may be large scale extinction of species and the loss of many ecosystems as we gain new (and fewer) homogenized ecosystems. Expect to hear more of the age of homogenization, whether you want to or not. The U. S. Department of Interior hosted an Eastern and Tropical States "Weed Summit" in Ft. Lauderdale, FL Nov 30 and Dec 1. The goal of the summit was to gather input and ideas from a broad spectrum of interest groups on actions and implementation strategies to combat invasive alien weeds. Representatives from this "summit" and an earlier western states "weed summit" will convene in Albuquerque February 11 to 14 to produce a recommended national strategy. This is indeed a promising development. The retirement of John Ebinger as Professor of Botany at Eastern Illinois University may well be the end of an era in Illinois. Students desiring in-depth training in native plant identification have found it increasingly difficult to find in recent years, and Ebinger's departure eliminates what has been their best opportunity in my opinion. -

Shawnee National Forest Map.Pdf

Ava 4 151 Johnson Creek 800-248-4373 To Chester 3 Kinkaid Lake www.southernmostillinois.com 14 Miles 127 Buttermilk Lake Hill (Boat in) Murphysboro State Park Murphysboro 149 To Mt. Vernon ek Middle Mississippi River re Carterville 45 Miles C National Wildlife Refuge rd ha rc Exit 54 O P b ra To Norris City o A - B 13 C To Carmi B p i g l Crab 22 Miles a Harrisburg 30 Miles M r u Orchard 13 d Marion 13 d y R Crab Orchard Lake Equality Gorham i R i d Exit 53 ve Carbondale g r e Ohio River Sahara Woods Saline Supervisors Visitor Center Shawneetown R G State Fish & Fountain Bluff D Vistor County Turkey i Office Oakwood a Center Wildlife Area Conservation n n Bottoms Bayou r t o t Area 13 h e t il E D ra R C T H Carrier i i t c Pomona y Mills Glen k Old Shawneetown Crab Orchard G o O. Jones r a Natural R 148 y National Lake r Little D Bridge d Wildlife Refuge 34 e R Grand n te i 145 37 d a To Morganfield Grand 3 Canyon o g St Stone f e t 12 Miles Tower Cedar Face h 57 e Mitchellsville Lake G R o D Little Grassy Exit 166 Rudement d Makanda 45 s Lake Devil R ll R D Hi D Pounds Hollow Kitchen Creal Springs k Inspiration Stonefort e Giant Lake a t t l e e Point Trail B f o r High r d C City D Lake R Garden of the Gods Exit 44 A - B O e Knob Panther Den l d To w n l Rim of g 1 H l 45 a u 1 Wilderness 145 Clear tc State ne E Rock h 5 n O in Egypt u Burden S s C T ali d Springs r e Park Wilderness n ee Alto t e a k Camp Cadiz R u Falls iv o Wilderness O a k Pass o R D e Karbers r H R S R Wilderness D M k R Ridge u e Delwood Herod d d y y 51 R D