Final Environmental Impact Statement Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

FISCAL YEAR 2020 ANNUAL REPORT March 2021

FISCAL YEAR 2020 ANNUAL REPORT March 2021 FCRPS Cultural Resources Program Rock imagery before and after graffiti removal at McNary site 45BN1753. FY 2020 Annual Report Under the FCRPS Systemwide Programmatic Agreement for the Management of Historic Properties – March 2021 This page intentionally left blank. 2 FY 2020 Annual Report Under the FCRPS Systemwide Programmatic Agreement for the Management of Historic Properties – March 2021 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS APE Area of Potential Effects ARPA Archaeological Resource Protection Act BPA Bonneville Power Administration CFR Code of Federal Regulations Corps U.S. Army Corps of Engineers CRITFE Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Enforcement CRMP Cultural Resources Management Plan CSKT Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation CTCR Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation CTUIR Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation CTWSRO Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon DAHP Washington Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation FCRPS Federal Columbia River Power System FCRPS Program FCRPS Cultural Resource Program FNF Flathead National Forest FY Fiscal year GIS Geographic Information Systems H/A CTCR History/Archaeology Program HMU Habitat management unit HPMP Historic Property Management Plan HPRCSIT Historic Property of Religious and Cultural Significance to Indian Tribes ID Idaho ISU Idaho State University KNF Kootenai National Forest 3 FY 2020 Annual Report Under the FCRPS Systemwide Programmatic Agreement for the Management of Historic Properties – March 2021 Lead Federal Bonneville Power Administration, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Agencies and the Bureau of Reclamation LiDAR Light detection and ranging MPD Multiple Property Documentation MT Montana NAGPRA Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Nez Perce/NPT Nez Perce Tribe NHPA National Historic Preservation Act NPS National Park Service NPTCRP Nez Perce Tribe Cultural Resource Program NRHP National Register of Historic Places NWP Portland District, U.S. -

1 Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Minutes of the 206

Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Minutes of the 206th Meeting (Approved at the 207th Meeting) Burpee Museum of Natural History 737 North Main Street Rockford, IL 61103 Tuesday, September 21, 2010 206-1) Call to Order, Roll Call, and Introduction of Attendees At 10:05 a.m., pursuant to the Call to Order of Chair Riddell, the meeting began. Deborah Stone read the roll call. Members present: George Covington, Donnie Dann, Ronald Flemal, Richard Keating, William McClain, Jill Riddell, and Lauren Rosenthal. Members absent: Mare Payne and David Thomas. Chair Riddell stated that the Governor has appointed the following Commissioners: George M. Covington (replacing Harry Drucker), Donald (Donnie) R. Dann (replacing Bruce Ross- Shannon), William E. McClain (replacing Jill Allread), and Dr. David L. Thomas (replacing John Schwegman). It was moved by Rosenthal, seconded by Flemal, and carried that the following resolution be approved: The Illinois Nature Preserves Commission wishes to recognize the contributions of Jill Allread during her tenure as a Commissioner from 2000 to 2010. Jill served with distinction as Chair of the Commission from 2002 to 2004. She will be remembered for her clear sense of direction, her problem solving abilities, and her leadership in taking the Commission’s message to the broader public. Her years of service with the Commission and her continuing commitment to and advocacy for the Commission will always be greatly appreciated. (Resolution 2089) It was moved by Rosenthal, seconded by Flemal, and carried that the following resolution be approved: The Illinois Nature Preserves Commission wishes to recognize the contributions of Harry Drucker during his tenure as a Commissioner from 2001 to 2010. -

Charles Springer of Cranehook-On-The-Delaware His Descendants and Allied Families by Jessie Evelyn Springer

Charles Springer of Cranehook-on-the-Delaware His Descendants and Allied Families By JESSIE EVELYN SPRINGER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For help on Springer research grateful acknow ledgment is extended to Mrs. Courtland B. Springer of Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, Mrs. Louise Eddleman, -Springfield, Kentucky, Mable Warner Milligan, Indian apolis, now deceased; the allied families, Gary Edward Young; John McKendree Springer, now deceased; Thomas Oglesby Springer and Lucinda Irwin, deceased; and Mary, Raymond and Theora Hahn. Much material has been secured from genealogies previously pub lished on the Benedicts, Saffords, Bontecous, and others, brought down to date by correspondence or interviews with Cora Taintor Brown, Springfield, Illi nois; Evelyn Safford Dew, Newark, Delaware; Isabell Gillham Crowder Helgevold, Chicago; John Harris Watts, Grand Junction, Iowa, and Glenn L. Head, Springfield, Illinois Charles Springer of Cranehook-on-the-Delaware His Descendants and Allied Families by Jessie Evelyn Springer OUR HERITAGE FORWORD Sarah John English has said "Genealogy, or the history of families, is not a service to the past gener ations, or a glorification of the dead, but a service to the living, and to coming generations." A study of those who gave us life can help us understand what makes us tick, and help us tolerate ourselves and each other. As this is the story of the heritage of four Springer sisters - Mary Springer Jackson, Florence Springer Volk, Carolyn Springer Dalton, and Jessie Springer, spinster, it seems best, to the writer, after -

The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: an Administrative History. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 266 012 SE 046 389 AUTHOR Paige, John C. TITLE The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO NPS-D-189 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 293p.; Photographs may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conservation (Environment); Employment Programs; *Environmental Education; *Federal Programs; Forestry; Natural Resources; Parks; *Physical Environment; *Resident Camp Programs; Soil Conservation IDENTIFIERS *Civilian Conservation Corps; Environmental Management; *National Park Service ABSTRACT The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) has been credited as one of Franklin D. Roosevelt's most successful effortsto conserve both the natural and human resources of the nation. This publication provides a review of the program and its impacton resource conservation, environmental management, and education. Chapters give accounts of: (1) the history of the CCC (tracing its origins, establishment, and termination); (2) the National Park Service role (explaining national and state parkprograms and co-operative planning elements); (3) National Park Servicecamps (describing programs and personnel training and education); (4) contributions of the CCC (identifying the major benefits ofthe program in the areas of resource conservation, park and recreational development, and natural and archaeological history finds); and (5) overall -

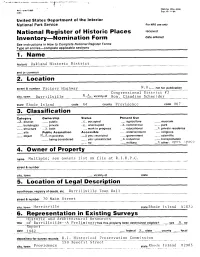

National Register of Historic Places Inventoiynomination Form 1. Name

___ _______ _____ I.. .- i.,,.z,...,.....a.......... __-_........,_...-4.. - -*_3__********_***____ - 0MB No 1024-0010 NP:’, orm ¶0-900 Cxp, 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received InventoiyNomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name -- t’istoric__Oakland Historic District and or common 2. Location street& number VictoryHigway_____ N. A Congressional District #2 city.town Burrillyille N.vicinityot Hon. Claudine Schneider state Rhode Is land code 44 county Providence code 007 3. Classification Category Ownership Status - Present Use ._L district public x occupied agriculture museum buildings private x unoccupied ._JL commercial park structure X.both - work in progress educational - X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object NA.in process _.X yes: restricted government scientific being considered - yes: unrestricted X industrial transportation Opel, a c’c no military . other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple see owners list on file at R. I .11. p . C. street & number city, town vicinity of. state 5. Location Of Legal Description - courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Burril lville Town Hal I street& number 70 Main Street city,town l:!arrisville stateRhode island 02833 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic and Architectural Resources title of Burrillville--A Preliminaryhas this property been determined -

Master Plan 2008 Re- Examination

TOWN OF MORRISTOWN MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY MASTER PLAN 2008 RE- EXAMINATION 2003 Master Plan Prepared by and adopted by The Morristown Planning Board August 14, 2003 Re-examination prepared by and adopted by the Morristown Planning Board September 25, 2008 Morristown Master Plan Re-Examination 2008 TRANSMITTAL AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS August 28, 2008 Chairwoman Mary Dougherty Morristown Planning Board 200 South Street Morristown, New Jersey 07963 Dear Chairwoman Dougherty: I am pleased to submit to the Planning Board this 2008 Re-examination of the 2003 Master Plan. The Re-examination was prepared in accordance with the provisions of NJSA40:55D-89. It was presented to the Board and posted on the Town’s web site on July 11, 2008 and discussed by the Board at it’s July 24, 2008 meeting. Because of their age and near obsolescence, the Zone Map, Schedule I and Schedule II were the first elements of the Master Plan to be re-examined. These documents were reviewed by the Long Range Planning Committee of the Planning Board and the public at four meetings between November 2006 and February 2007. Subsequently, they were reviewed by the full Planning Board and the public at two meetings in March 2007. They were presented to the Council on April 10, 2007 and after several meetings were approved on September 11, 2007. Note that this reexamination does not contain a Housing Element. Since the COAH regulations have not been finalized by the State as of this writing, the basic legislation necessary to prepare the Housing Element is yet to be enacted. -

Crab Orchard National Wildlife Refuge / Comprehensive Conservation Plan Ii Preface

Acknowledgments Acknowledgments Many people have contributed to this plan over many detailed and technical requirements of sub- the last seven years. Several key staff positions, missions to the Service, the Environmental Protec- including mine, have been filled by different people tion Agency, and the Federal Register. Jon during the planning period. Tom Palmer and Neil Kauffeld’s and Nita Fuller’s leadership and over- Vincent of the Refuge staff are notable for having sight were invaluable. We benefited from close col- been active in the planning for the entire extent. laboration and cooperation with staff of the Illinois Tom and Neil kept the details straight and the rest Department of Natural Resources. Their staff par- of us on track throughout. Mike Brown joined the ticipated from the early days of scoping through staff in the midst of the process and contributed new reviews and re-writes. We appreciate their persis- insights, analysis, and enthusiasm that kept us mov- tence, professional expertise, and commitment to ing forward. Beth Kerley and John Magera pro- our natural resources. Finally, we value the tremen- vided valuable input on the industrial and public use dous involvement of citizens throughout the plan- aspects of the plan. Although this is a refuge plan, ning process. We heard from visitors to the Refuge we received notable support from our regional office and from people who care about the Refuge without planning staff. John Schomaker provided excep- ever having visited. Their input demonstrated a tional service coordinating among the multiple level of caring and thought that constantly interests and requirements within the Service. -

Illinois Geography Lapbook Can Help You to Further Explore the Wonderful State of Illinois

Creating an Illinois Geography Lapbook can help you to further explore the wonderful state of Illinois. Basic instructions on creating a lapbook are available at the bottom of this page along with templates and images for use in your lapbook. Geography is more than just the physical make up of a location, it is also about the people, their interaction with the environment and nature. I hope to have touched on each of these in some way in this lapbook study. How to Use This Page You will find many facts and interesting items on this page and on the Illinois Geography page. There is too much information to include in a beginning lapbook session. Take a few minutes to first pick what you feel is important for your student to know or what might be interesting to him or her. I recommend no more than one or two items from each category per lapbooking session. The option to expand on this topic is always there but cover what you believe is important first. THEN Do activities that relate to the topic, for example the State dance is a Square Dance. Look up online the basic Square Dance steps and try them or take a Square Dancing class. Follow up by putting a dance diagram in the lapbook. Be creative in trying new things and experiment with more than the templates. If your child is artistic, let her/him draw. If your child learns by hands-on activities make an invention. Is your child musically inclined, sing the state song. -

Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team 2015 Annual Report

Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team 2015 Annual Report Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team 2015 Annual Report Prepared by: Caleb Grantham and Nick Seaton – Invasive Species Strike Team This program was funded through: A grant supported by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the United States Forest Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area Acknowledgements This program was funded through a grant supported by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Forest Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area Contributions to this report were provided by: Caleb Grantham and Nick Seaton, Invasive Species Strike Team; Karla Gage and Kevin Rohling, River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area; Jody Shimp, Natural Heritage Division, Illinois Department of Natural Resources; Tharran Hobson, The Nature Conservancy; Shannan Sharp, United States Forest Service; United States Fish and Wildlife Service 2015’s field season has been dedicated to District Heritage Biologist, Bob Lindsay, whose dedication and insight to the Invasive Species Strike Team was greatly appreciated and will be sincerely missed. Equal opportunity to participate in programs of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and those funded by the U.S.D.A Forest Service and other agencies is available to all individuals regardless of race, sex, national origin, disability, age, religion or other non-merit factors. If you believe you have been discriminated against, contact the funding source’s civil rights office and/or the Equal Employment Opportunity Officer, IDNR, One Natural Resources Way, Springfield, IL. -

Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team

Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team January, 2016 – April, 2017 Report Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team January 2016 – April 2017 Report Prepared by: Caleb Grantham – Invasive Species Strike Team Member This program was funded through: A grant supported by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the United States Forest Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area, and the Shawnee RC&D. - 0 - | P a g e Acknowledgements This program was funded through a grant supported by the United States Forest Service, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area, and the Shawnee RC&D. Contributions to this report were provided by: Caleb Grantham, Cody Langan, and Nick Seaton Invasive Species Strike Team; Kevin Rohling, River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area; Jody Shimp, Shawnee RC&D; Tharran Hobson, The Nature Conservancy; Shannan Sharp and Nate Hein, United States Forest Service; David Jones, United States Fish and Wildlife Service Equal opportunity to participate in programs of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and those funded by the U.S.D.A Forest Service and other agencies is available to all individuals regardless of race, sex, national origin, disability, age, religion or other non-merit factors. If you believe you have been discriminated against, contact the funding source’s civil rights office and/or the Equal Employment Opportunity Officer, IDNR, One Natural Resources Way, Springfield, IL. 62702-1271; 217/782-2262; TTY 217/782-9175. -

Great Rivers Sub-Area Contingency Plan

Great Rivers Subarea Contingency Plan U.S. Environmental Protection Agency October 2020 Public Distribution Great Rivers Subarea Contingency Plan EPA Region 7 TO REPORT A SPILL OR RELEASE National Response Center Emergency Response 24-Hour Emergency Number (800) 424-8802 National Response Center United States Coast Guard Headquarters Washington, DC EPA Region 5 Regional Response Center Emergency Response 24-Hour Emergency Number (312) 353-2318 United States Environmental Protection Agency Emergency Response Branch 77 West Jackson Blvd. Chicago, Illinois 60604 EPA Region 7 Regional Response Center Emergency Response 24-Hour Emergency Number (913) 281-0991 United States Environmental Protection Agency Emergency Response Branch 11201 Renner Blvd. Lenexa, Kansas 66219 EPA Region 4 Regional Response Center Emergency Response 24-Hour Emergency Number (404) 562-8700 United States Environmental Protection Agency Emergency Response Branch 61 Forsyth St. SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 United States Coast Guard Emergency Response 24-Hour Emergency Number (504) 589-6225 District Commander, Eighth District Hale Boggs Federal Building, Room 1328 500 Poydras Street New Orleans, Louisiana 70130 i Great Rivers Subarea Contingency Plan EPA Region 7 Sector Upper Mississippi River, Sector Commander 24-Hour Emergency Number: (314) 269-2332 1222 Spruce Street, Suite 7.103 Saint Louis, Missouri 63103 Sector Lower Mississippi River, Sector Commander 24-Hour Emergency Number: (901) 521-4804 2 AW Willis Avenue Memphis, Tennessee 38105 Sector Ohio Valley, Sector Commander