Washington Athletic Club Was Designed by Sherwood D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Seattle Branch 1949-50

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Seattle Branch 1949-50 1015 Second Avenue 093900-0520 see below C. D. BOREN AND A. A. DENNY 12 2, 3, 6, 7 LOTS 2, 3, 6 AND 7, BLOCK 12, TOWN OF SEATTLE, AS LAID OUT ON THE CLAIMS OF C. D. BOREN AND A. A. DENNY (COMMONLY KNOWN AS BOREN & DENNY’S ADDITION TO THE CITY OF SEATTLE) ACCORDING TO PLAT THEREOF RECORDED IN VOLUME 1 OF PLATS, PAGE 27, RECORDS OF KING COUNTY, EXCEPT THE EASTERLY 12 FEET THEREOF CONDEMNED IN DISTRICT COURT CASE NO. 7097 FOR SECOND AVENUE, AS PROVIDED BY ORDINANCE NO. 1107 OF THE CITY OF SEATTLE. 1015 Second Avenue LLC vacant c/o Martin Selig Real Estate, Attention Pete Parker, 1000 Second Avenue, Suite 1800, Seattle, WA 98104-1046. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Bank Naramore, Bain, Brady, and Johanson (William J. Bain, project principal) Engineer: W. H. Witt Company (George Runciman, project engineer) Kuney Johnson Company Pete Parker c/o Martin Selig Real Estate, Attention Pete Parker, 1000 Second Avenue, Suite 1800, Seattle, WA 98104-1046. (206) 467-7600. October 2015 Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Seattle Branch Bank Landmark Nomination Report 1015 Second Avenue, Seattle October 2015 Prepared by: The Johnson Partnership 1212 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-6724 206-523-1618, www.tjp.us Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Seattle Branch Landmark Nomination Report October 2015, page i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 City of Seattle Landmark Nomination Process ...................................................................... 2 1.3 Methodology ....................................................................................................................... -

Zoning ORDINANCE USER's MANUAL

CITY OF PROVIDENCEPROVIDENCE ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL PRODUCED BY CAMIROS ZONING ORDINANCE USER'S MANUAL WHAT IS ZONING? The Zoning Ordinance provides a set of land use and development regulations, organized by zoning district. The Zoning Map identifies the location of the zoning districts, thereby specifying the land use and develop- ment requirements affecting each parcel of land within the City. HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL This User’s Manual is intended to provide a brief overview of the organization of the Providence Zoning Ordinance, the general purpose of the various Articles of the ordinance, and summaries of some of the key ordinance sections -- including zoning districts, uses, parking standards, site development standards, and administration. This manual is for informational purposes only. It should be used as a reference only, and not to determine official zoning regulations or for legal purposes. Please refer to the full Zoning Ordinance and Zoning Map for further information. user'’S MANUAL CONTENTS 1 ORDINANCE ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 2 ZONING DISTRICTS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 3 USES............................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION N 980314 ZRM Subway

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION July 20, 1998/Calendar No. 3 N 980314 ZRM IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by the Department of City Planning, pursuant to Section 201 of the New York City Charter, to amend various sections of the Zoning Resolution of the City of New York relating to the establishment of a Special Lower Manhattan District (Article IX, Chapter 1), the elimination of the Special Greenwich Street Development District (Article VIII, Chapter 6), the elimination of the Special South Street Seaport District (Article VIII, Chapter 8), the elimination of the Special Manhattan Landing Development District (Article IX, Chapter 8), and other related sections concerning the reorganization and relocation of certain provisions relating to pedestrian circulation and subway stair relocation requirements and subway improvements. The application for the amendment of the Zoning Resolution was filed by the Department of City Planning on February 4, 1998. The proposed zoning text amendment and a related zoning map amendment would create the Special Lower Manhattan District (LMD), a new special zoning district in the area bounded by the West Street, Broadway, Murray Street, Chambers Street, Centre Street, the centerline of the Brooklyn Bridge, the East River and the Battery Park waterfront. In conjunction with the proposed action, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development is proposing to amend the Brooklyn Bridge Southeast Urban Renewal Plan (located in the existing Special Manhattan Landing District) to reflect the proposed zoning text and map amendments. The proposed zoning text amendment controls would simplify and consolidate regulations into one comprehensive set of controls for Lower Manhattan. -

CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 12. 1978~ Designation List 118 LP-0992 CHRYSLER BUILDING, 405 Lexington Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1928- 1930; architect William Van Alen. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1297, Lot 23. On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a_public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Chrysler Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 12). The item was again heard on May 9, 1978 (Item No. 3) and July 11, 1978 (Item No. 1). All hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirteen witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were two speakers in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters and communications supporting designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Chrysler Building, a stunning statement in the Art Deco style by architect William Van Alen, embodies the romantic essence of the New York City skyscraper. Built in 1928-30 for Walter P. Chrysler of the Chrysler Corporation, it was "dedicated to world commerce and industry."! The tallest building in the world when completed in 1930, it stood proudly on the New York skyline as a personal symbol of Walter Chrysler and the strength of his corporation. History of Construction The Chrysler Building had its beginnings in an office building project for William H. Reynolds, a real-estate developer and promoter and former New York State senator. Reynolds had acquired a long-term lease in 1921 on a parcel of property at Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street owned by the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. -

Seattle: Queen City of the Pacific Orn Thwest Anonymous

University of Mississippi eGrove Haskins and Sells Publications Deloitte Collection 1978 Seattle: Queen city of the Pacific orN thwest Anonymous James H. Karales Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/dl_hs Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation DH&S Reports, Vol. 15, (1978 autumn), p. 01-11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Deloitte Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Haskins and Sells Publications by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^TCAN INSTITUTE OF JC ACCOUNTANTS Queen City Seattle of the Pacific Northwest / eattle, Queen City of the Pacific Located about as far north as the upper peratures are moderated by cool air sweep S Northwest and seat of King County, corner of Maine, Seattle enjoys a moderate ing in from the Gulf of Alaska. has been termed by Harper's and other climate thanks to warming Pacific currents magazines as America's most livable city. running offshore to the west. The normal Few who reside there would disagree. To a maximum temperature in July is 75° Discussing special exhibit which they just visitor, much of the fascination of Seattle Fahrenheit, the normal minimum tempera visited at the Pacific Science Center devoted lies in the bewildering diversity of things to ture in January is 36°. Although the east to the Northwest Coast Indians are (I. to r.) do and to see, in the strong cultural and na ward drift of weather from the Pacific gives DH&S tax accountants Liz Hedlund and tional influences that range from Scandina the city a mild but moist climate, snowfall Shelley Ate and Lisa Dixon, of office vian to Oriental to American Indian, in the averages only about 8.5 inches a year, administration. -

Kirtland Kelsey Cutter, Who Worked in Spokane, Seattle and California

Kirtland Kelsey 1860-1939 Cutter he Arts and Crafts movement was a powerful, worldwide force in art and architecture. Beautifully designed furniture, decorative arts and homes were in high demand from consumers in booming new cities. Local, natural materials of logs, shingles and stone were plentiful in the west and creative architects were needed. One of them was TKirtland Kelsey Cutter, who worked in Spokane, Seattle and California. His imagination reflected the artistic values of that era — from rustic chapels and distinctive homes to glorious public spaces of great beauty. Cutter was born in Cleveland in 1860, the grandson of a distinguished naturalist. A love of nature was an essential part of Kirtland’s work and he integrated garden design and natural, local materials into his plans. He studied painting and sculp- ture in New York and spent several years traveling and studying in Europe. This exposure to art and culture abroad influenced his taste and the style of his architecture. The rural buildings of Europe inspired him throughout his career. One style associated with Cutter is the Swiss chalet, which he used for his own home in Spokane. Inspired by the homes of the Bernese Oberland region of Switzerland, it featured deep eaves that extended out from the roofline. The inside was pure Arts and Crafts, with a rustic, tiled stone fireplace, stained glass windows and elegant woodwork. Its simplicity contrasted with the grand homes many of his clients requested. The railroads brought people to the Northwest looking for opportunities in mining, logging and real estate. My great grandfather, Victor Dessert, came from France and settled in Spokane in the 1880s. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Arctic Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 306 Cherry Si _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN & CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle __ VICINITY OF 1 st Joel Pri tchard STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington 53 King 033 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH X-WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: CHG Citv Center Investors # 6 STREET & NUMBER 1906 One Washington Plaza CITY, TOWN STATE ____Tacoma VICINITY OF Washington 98402 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEED^ETC. Assessors Qff| ce , King County Admi ni s trati on Buil di nq STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Seattle Washington REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Washington State Inventory of Historic Places DATE February 1978 —FEDERAL ^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Qff1ce Of Archaeology and Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Olympia Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Arctic Building,occupying a site at the corner of Third Avenue and Cherry Street in Seattle, rises eight stories above a ground level of retail shops to an ornate terra cotta roof cornice. -

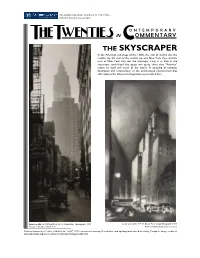

The Skyscraper of the 1920S

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION ONTEMPORAR Y IN OMMENTARY HE WENTIES T T C * THE SKYSCRAPER In the American self-image of the 1920s, the icon of modern was the modern city, the icon of the modern city was New York City, and the icon of New York City was the skyscraper. Love it or hate it, the skyscraper symbolized the go-go and up-up drive that “America” meant to itself and much of the world. A sampling of twenties illustration and commentary on the architectural phenomenon that still captures the American imagination is presented here. Berenice Abbott, Cliff and Ferry Street, Manhattan, photograph, 1935 Louis Lozowick, 57th St. [New York City], lithograph, 1929 Museum of the City of New York Renwick Gallery/Smithsonian Institution * ® National Humanities Center, AMERICA IN CLASS , 2012: americainclass.org/. Punctuation and spelling modernized for clarity. Complete image credits at americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/imagecredits.htm. R. L. Duffus Robert L. Duffus was a novelist, literary critic, and essayist with New York newspapers. “The Vertical City” The New Republic One of the intangible satisfactions which a New Yorker receives as a reward July 3, 1929 for living in a most uncomfortable city arises from the monumental character of his artificial scenery. Skyscrapers are undoubtedly popular with the man of the street. He watches them with tender, if somewhat fearsome, interest from the moment the hole is dug until the last Gothic waterspout is put in place. Perhaps the nearest a New Yorker ever comes to civic pride is when he contemplates the skyline and realizes that there is and has been nothing to match it in the world. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

Height, Setbacks, and Floor Area 17.48

HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA 17.48 Chapter 17.48 – HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA Sections: 17.48.010 Purpose 17.48.020 Height Measurement and Exceptions 17.48.030 Setback Measurement and Exceptions 17.48.040 Floor Area and Floor Area Ratio 17.48.010 Purpose This chapter establishes rules for the measurement of height, setbacks, and floor area, and permitted exceptions to height and setback requirements. 17.48.020 Height Measurement and Exceptions A. Measurement of Height. 1. The height of a building is measured as the vertical distance from the assumed ground surface to the highest point of the building. 2. Assumed ground surface means a line on the exterior wall of a building that connects the points where the perimeter of the wall meets the finished grade. See Figure 17.48-1. 3. If grading or fill on a property within five years of an application increases the height of the assumed ground service, height shall be measured using an estimation of the assumed ground surface as it existed prior to the grading or fill. FIGURE 17.48-1: MEASUREMENT OF MAXIMUM PERMITTED BUILDING HEIGHT 48-1 17.48 HEIGHT, SETBACKS, AND FLOOR AREA B. Height Exceptions. Buildings may exceed the maximum permitted height in the applicable zoning district as shown in Table 17.48-1. Note: Height exceptions in Table 17.48-1 below add detail to height exceptions in Section 17.81.070 of the existing Zoning Code. TABLE 17.48-1: ALLOWED PROJECTIONS ABOVE HEIGHT LIMITS Maximum Projection Above Structures Allowed Above Height Limit Maximum Coverage Height Limit Non-habitable decorative features including 3 ft. -

LPB 220/21 MINUTES Landmarks Preservation Board Meeting City

LPB 220/21 MINUTES Landmarks Preservation Board Meeting City Hall Remote Meeting Wednesday May 5, 2021 - 3:30 p.m. Board Members Present Staff Dean Barnes Sarah Sodt Roi Chang Erin Doherty Jordan Kiel Melinda Bloom Kristen Johnson John Rodezno Harriet Wasserman Absent Russell Coney Matt Inpanbutr Chair Jordan Kiel called the meeting to order at 3:30 p.m. In-person attendance is currently prohibited per Washington State Governor's Proclamation No. 20-28.5. Meeting participation is limited to access by the WebEx Event link or the telephone call-in line provided on agenda. ROLL CALL 050521.1 PUBLIC COMMENT 1 Elizabeth Wales, Fairfax resident spoke in support of nomination. She said it meets the standard as an identifiable, known and cool building; the pure Gothic Revival architectural style, which is rare in Seattle; and for architect James Eustace Blackwell. She said there are many intangibles – how it feels to live here; she noted the beautiful leaded glass and said that beauty creeps into daily life. She noted the beautiful details molded into the whole. She said to please nominate the exterior of the building. She said the building is an example of handsome architecture and understated beauty for housing the middle class. She said she resists the idea that middle class and low-income housing cannot be beautiful. Ms. Wasserman joined the meeting during public comment. 050521.2 MEETING MINUTES April 7, 2021 Tabled. 050521.3 CERTIFICATES OF APPROVAL 050521.31 Rosen House 9017 Loyal Avenue NW Proposed addition and site improvements Sonya Schneider and Stuart Nagae, the property owners said they love the house and appreciate the craft and its sense of integrity. -

Zoning Handbook 1961

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION • DEPARTMENT OF CITY PLANNING ZONING HANDBOOK A Guide to the Zoning Resolution of The City of New York TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ............................................ >................. _ ••••• __••••••• __ ............................ 4 THE STRUCTURE OF THE RESOLUTION Zoning Maps ............................................................ _........................ _............................. 6 Text of the Resolution ................................................................................................ 7 Index of Uses ........................................................ ........................................................ 8 USE Use Groups and Special Permit Uses ....................................... __ .......................... 10 Use Districts .......................................................... _.......................... __ •......................... 12 Industrial Performance Standards (Manufacturing Districts) .............................................. _ .............................. 13 Supplementary Use Regulations and Special Provisions Along District Boundaries ............................................ 14 Signs ................................................................................................... _.............................. 14 BULK Controls Over Intensity of Development .............................................................. 16 Design Controls ........... ..................................................................................................