Integrating Environment and Local Development in Tigray Region of Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Dairy Production and Management Practice Under Small Holder Farmer in Adigrat Town

Journal of Natural Sciences Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3186 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0921 (Online) Vol.7, No.13, 2017 Assessment of Dairy Production and Management Practice under Small Holder Farmer in Adigrat Town Abadi Nigus 1* Zemede Ashebo 2 Tekeste Zenebe 2 Tamirat Adimasu 2 1.Department of Animal Sciences, Adigrat University, P.O.Box 50, Adigrat, Ethiopia 2.Department of Animal Sciences, Adigrat University, P.O.Box 50, Adigrat, Ethiopia Abstract The study was conducted in Adigrat town and aimed at assessing the dairy cattle production, management practices and constraints associated to milk production under smallholder. The data was collected by questionnaire from three purposively selected Kebeles (02, 04, and 05) and 30 respondents that are 10 selected householders from each Kebeles. The major feed resources in the study area were hay, crop residues and by- products of the local beverages Atella (lees) and industrial by products such as wheat bran and noug seed cake. The major constraints to milk production in the study area were feed shortage, disease prevalence and low milk yield. Disease is one of the major problems associated with dairy production or milk production system that causes mortality and reduced milk production. Also, in the study area the following management practices are assessed feeds and feeding, breeding using Artificial insemination (56.67%) and natural services (43.33%), housing system, healthcare and other manure handling. In addition, in the area hand milking is the sole milking method practiced in all the study area. Frequency of milking across the dairy production systems of the area was twice daily. -

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Local History of Ethiopia an - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia An - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) an (Som) I, me; aan (Som) milk; damer, dameer (Som) donkey JDD19 An Damer (area) 08/43 [WO] Ana, name of a group of Oromo known in the 17th century; ana (O) patrikin, relatives on father's side; dadi (O) 1. patience; 2. chances for success; daddi (western O) porcupine, Hystrix cristata JBS56 Ana Dadis (area) 04/43 [WO] anaale: aana eela (O) overseer of a well JEP98 Anaale (waterhole) 13/41 [MS WO] anab (Arabic) grape HEM71 Anaba Behistan 12°28'/39°26' 2700 m 12/39 [Gz] ?? Anabe (Zigba forest in southern Wello) ../.. [20] "In southern Wello, there are still a few areas where indigenous trees survive in pockets of remaining forests. -- A highlight of our trip was a visit to Anabe, one of the few forests of Podocarpus, locally known as Zegba, remaining in southern Wello. -- Professor Bahru notes that Anabe was 'discovered' relatively recently, in 1978, when a forester was looking for a nursery site. In imperial days the area fell under the category of balabbat land before it was converted into a madbet of the Crown Prince. After its 'discovery' it was declared a protected forest. Anabe is some 30 kms to the west of the town of Gerba, which is on the Kombolcha-Bati road. Until recently the rough road from Gerba was completed only up to the market town of Adame, from which it took three hours' walk to the forest. A road built by local people -- with European Union funding now makes the forest accessible in a four-wheel drive vehicle. -

PHE EC Newsletter No 4

PHE Ethiopia Consortium Newsletter Fourth Edition, January - June, 2011 Our Voice th >> The 5 General Assembly Meeting >> Third National Earth Day Celebration >> GO - GREEN Africa HPB PHE Ethiopia Consortium Newsletter Issue No. 4 PHE Ethiopia Consortium Newsletter Issue No. 4 1 PHE Ethiopia Consortium P. O. Box: 4408 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Phone: +251 11 8608190 +251 11 663 0833 Director’s Note Fax: +251 11 663 8127 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.phe-ethiopia.org Dear PHE Ethiopia supporters and readers, elcome to the fourth issue of PHE’s Newsletter “Our Voice” that Whighlights the recent activities of the Consortium. Since Population, Health and environment (PHE) interventions in Preaired by Ethiopia are a holistic, participatory and proactive development approach whereby issues of environment, health and population are addressed in Negash Teklu an integrated manner for improved livelihoods and sustainable well-being Mesfin Kassa of people and ecosystems. In addition the Consortium’s vision is to see Mahlet Tesfaye Ethiopia with healthy population, sustainable resource use, improved Dagim Gezahegn livelihood and resilient ecosystem. As always, this issue includes the major activities performed during the Edited by last six months from January to June, 2011 and an interview with Heather D’Agnes, USAID Washington Population Environment Technical Advisor Negash Teklu within the Agency’s Global Health Bureau. Jason Bremner We hope you will enjoy reading about our accomplishments. Designed & Printed by Negash Teklu PHILMON PRESS Executive Director (0911644678) PHE Ethiopia Consortium In this Issue: th 2 The 5 General Assembly meeting 6 Workshop on Members and Partners Regular joint Review Meeting 8 Interview with Heather D”Agnes 11 Third National Earth Day Celebration 12 Workshop in Climate Change and Development in Rural Ethiopia 15 BARR Foundation Visit to Ethiopia 15 Media Capacity Building 13 Weathering Change Film Launching Program 16 EXPERIENCE SHARING FIELD VISIT TO THE SOUTH 17 International Women Edition Program visit in Ethiopia .. -

Sustainable Land Management Ethiopia

www.ipms-ethiopia.org www.eap.gov.et Working Paper No. 21 Sustainable land management through market-oriented commodity development: Case studies from Ethiopia This working paper series has been established to share knowledge generated through Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers project with members of the research and development community in Ethiopia and beyond. IPMS is a five-year project funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and implemented by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) on behalf of the Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MoARD). Following the Government of Ethiopia’s rural development and food security strategy, the IPMS project aims at contributing to market-oriented agricultural progress, as a means for achieving improved and sustainable livelihoods for the rural population. The project will contribute to this long-term goal by strengthening the effectiveness of the Government’s efforts to transform agricultural production and productivity, and rural development in Ethiopia. IPMS employs an innovation system approach (ISA) as a guiding principle in its research and development activities. Within the context of a market-oriented agricultural development, this means bringing together the various public and private actors in the agricultural sector including producers, research, extension, education, agri-businesses, and service providers such as input suppliers and credit institutions. The objective is to increase access to relevant knowledge from multiple sources and use it for socio-economic progress. To enable this, the project is building innovative capacity of public and private partners in the process of planning, implementing and monitoring commodity-based research and development programs. -

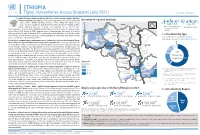

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Modeling Malaria Cases Associated with Environmental Risk Factors in Ethiopia Using Geographically Weighted Regression

MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION Berhanu Berga Dadi i MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING THE GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION MODEL, 2015-2016 Dissertation supervised by Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques,PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain Ana Cristina Costa, PhD Professor, Nova Information Management School University of Nova Lisbon, Portugal Pablo Juan Verdoy, PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain March 2020 ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that the work described in this document is my own and not from someone else. All the assistance I have received from other people is duly acknowledged, and all the sources (published or not published) referenced. This work has not been previously evaluated or submitted to the University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain, or elsewhere. Castellon, 30th Feburaury 2020 Berhanu Berga Dadi iii Acknowledgments Before and above anything, I want to thank our Lord Jesus Christ, Son of GOD, for his blessing and protection to all of us to live. I want to thank also all consortium of Erasmus Mundus Master's program in Geospatial Technologies for their financial and material support during all period of my study. Grateful acknowledgment expressed to Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques, Universitat Jaume I(UJI), Prof.Dr.Ana Cristina Costa, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, and Prof.Dr.Pablo Juan Verdoy, Universitat Jaume I(UJI) for their immense support, outstanding guidance, encouragement and helpful comments throughout my thesis work. Finally, but not least, I would like to thank my lovely wife, Workababa Bekele, and beloved daughter Loise Berhanu and son Nethan Berhanu for their patience, inspiration, and understanding during the entire period of my study. -

20Th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies ፳ኛ የኢትዮጵያ ጥናት ጉባኤ

20th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies ኛ ፳ የኢትዮጵያ ጥናት ጉባኤ Regional and Global Ethiopia – Interconnections and Identities 30 Sep. – 5 Oct. 2018 Mekelle University, Ethiopia Message by Prof. Dr. Fetien Abay, VPRCS, Mekelle University Mekelle University is proud to host the International Conference of Ethiopian Studies (ICES20), the most prestigious conference in social sciences and humanities related to the region. It is the first time that one of the younger universities of Ethiopia has got the opportunity to organize the conference by itself – following the great example set by the French team of the French Centre of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Abeba organizing the ICES in cooperation with Dire Dawa University in 2012, already then with great participation by Mekelle University academics and other younger universities of Ethiopia. We are grateful that we could accept the challenge, based on the set standards, in the new framework of very dynamic academic developments in Ethiopia. The international scene is also diversifying, not only the Ethiopian one, and this conference is a sign for it: As its theme says, Ethiopia is seen in its plural regional and global interconnections. In this sense it becomes even more international than before, as we see now the first time a strong participation from almost all neighboring countries, and other non-Western states, which will certainly contribute to new insights, add new perspectives and enrich the dialogue in international academia. The conference is also international in a new sense, as many academics working in one country are increasingly often nationals of other countries, as more and more academic life and progress anywhere lives from interconnections. -

Buch Ass.Pdf

Adigrat Diocesan Development Action The Eparchy of Adigrat, Tigray Ethiopia Text: Kevin O’Mahoney, M.Afr. Illustration & Layout: Paula Troxler on the dam, what prohibited work during rainy times. rainy during work prohibited what dam, the on ing a concrete mix the beginning, In flooding. to exposed to foundation 5 meter height in often 2002. Works Photographs from the start of dam raise, from the nd a ggregat e a Photographs from the starting phase of Assabol ccumulation dam in 1997. Blasting works for the gorge access road and the dam abutments, searching for best dam site with the help of iron bars, excavating the foundation and boulder breaking, access works and casting of foundation. w as d one d irectly - Dieter Nussbaum, Caritas Switzerland, Endrias Gebray and Bruno Strebel, plus Abba Hagos Woldu with Woreda Chairman Gebreh. View towards gorge Assabol, Dawhan during river flood, and fourphotos from upper watershed landscape. Blasting expert Reini Schrämli The larger photo shows the Assabol (means Red and civil engineer Urs Schaffner. Cliff) and Kinkintay (means Ringing Stone) mountains meeting point of the two main con- from the downstream side. In the centre the gorge tributing rivers at Asmuth during with the dam ly. These two rock outcrops are part rainy season, various landscapes of of a geological ring dike of very hard quarzporphyr the upper watershed. rock, what provided perfect dam site conditions. Assabol dam construction from 2003 until 2004: In 2005 the dam steadily grew thanks to flood se- Collection of sand and gravel, boat access and cured concrete casting by now well functioning hose siphoning, first experiences with heavy cable crane. -

The Impact of Fencing on Regeneration, Tree Growth and Carbon Stock in Desa Forest, Tigray, Ethiopia

ISSN: 2574-1241 Volume 5- Issue 4: 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.12.002183 Guo Ruo. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res Research Article Open Access The Impact of Fencing on Regeneration, Tree Growth and Carbon Stock in Desa Forest, Tigray, Ethiopia Guo Ruo1*, Brhane Weldegebrial2, Genet Yohannes3 and Gebremedhin Yohannes4 1College of Enviromental Science and Engineering, Tongjji University, China 2College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Tongjji University, China 3College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Gambella University, Ethiopia 4College of Veterinary Medicine, Hawassa University, Ethiopia Received: : November 27, 2018; Published: : December 11, 2018 *Corresponding author: Guo Ruo, College of Enviromental Science and Engineering, Tongjji University, China Abstract Dryland forests of Ethiopia are facing a rapid rate of deforestation and degradation. This affects the growth and survival of plant density, diversity, growth and carbon stock. The aim of the study was to investigate the effect of fencing on regeneration, bonsai growth and carbon stock growth on permanent plots established in 2009. Data were analyzed using paired t-test to estimate any change on regeneration and carbon stock potential of Desa‟a forests. Data were collected on 24 plots of 20m×20m for trees and shrubs, 5m×5m for seedlings and on 40m×40m for bonsai carbon stock and bonsai growth between fenced and unfenced. Results showed that a total of 27 woody species were found representing 18 families. Oleawithin europaea the fenced subspecies and unfenced cuspidata block and over Juniperus time. However, procera were an independent with the highest t-test Importance was used to Value measure Index. any The significant overall diameter difference distribution on regeneration, showed an inverted J-shape indicating active regeneration status. -

Download E-Book (PDF)

African Journal of Political Science and International Relations Volume 11 Number 9 September 2017 ISSN 1996-0832 ABOUT AJPSIR The African Journal of Political Science and International Relations (AJPSIR) is published monthly (one volume per year) by Academic Journals. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations (AJPSIR) is an open access journal that publishes rigorous theoretical reasoning and advanced empirical research in all areas of the subjects. We welcome articles or proposals from all perspectives and on all subjects pertaining to Africa, Africa's relationship to the world, public policy, international relations, comparative politics, political methodology, political theory, political history and culture, global political economy, strategy and environment. The journal will also address developments within the discipline. Each issue will normally contain a mixture of peer-reviewed research articles, reviews or essays using a variety of methodologies and approaches. Contact Us Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJPSIR Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/ Editors Dr. Thomas Kwasi Tieku Dr. Aina, Ayandiji Daniel Faculty of Management and Social Sciences New College, University of Toronto Babcock University, Ilishan – Remo, Ogun State, 45 Willcocks Street, Rm 131, Nigeria. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Prof. F. J. Kolapo Dr. Mark Davidheiser History Department University of Guelph Nova Southeastern University 3301 College Avenue; SHSS/Maltz Building N1G 2W1Guelph, On Canada Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314 USA. Dr. Nonso Okafo Graduate Program in Criminal Justice Dr. Enayatollah Yazdani Department of Political Science Department of Sociology Norfolk State University Faculty of Administrative Sciences and Economics University of Isfahan Norfolk, Virginia 23504 Isfahan Iran.