EWC Oral History Coverpage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and Identity Ofthe Cultural Renaissance of Hawai·I A

-022.\ CONNECT BACK TO DIS PIACE: Music and Identity ofthe Cultural Renaissance ofHawai·i A '!HESIS SUBMITTED TO '!HE GRADUATE DIVISION OF '!HE UNIVERSI1Y OF HAWAI·I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF '!HE REQUIREMENTS FOR '!HE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PACIFIC ISLAND STUDIES MAY 2005 By Andrea A Suzuki Thesis Conunittee: Kater1na Teaiwa. Chairperson George Teny Kanalu Young Jonathan K. 050110 Acknowledgements First and foremost I have to thank my parents. especIally Daddy MIke for the opJX>rtun1ties that they have gtven me and their sUpJX>rt gtven to my endeavors. I have to also thank Daddy Mitch for hIs sUPJX>rt and h1s stortes about "h1s days". I want to especIally thank my mom, an AM.A 1n her own rtght, for all ofher devoted time and sUPJX>rt. Secondly, I would l1ke to gIve my deepest thanks to Mel1nda Caroll wIthout whom th1s jOurney would have been a lot more d1ff1cult. Thankyou for your suggestions, your help, and your encouragement. I would also l1ke to thank my comm11tee, Katertna Tea1Wa, Kanalu Young, and John Osorto for their sUpJX>rt and theIr efforts 1n the completion ofth1s project. I'd l1ke to thank all ofthose that gave their time to me, tell1ng me their stortes. and allowtng me to share those stortes: Jeny Santos, Owana Salazar, Aunty CookIe, Uncle Cyr11. Hemy KapollO, John Demello. Gaylord Holomal1a, Keaum1k1 Akut. Peter Moon, and Joe Atpa. I'd l1ke to gIve my appreciation to the Pac1ftc Island StudIes Program that guIded me every' step ofthe way. F1nallly. I'd 11ke to thank all my frIends for their encouragement and tolerance ofmy 1nsan1ty, espec1ally Kamuela Andrade, for gJ.1nn1ng and beartng It and Kau1 for beIng my personal cheering section. -

The Hawai'i Tourism Authority

)~ ‘-1 I Hawai'i Convention Center David v. lge ,=';'7" ‘ " I “M 1801 Kalékaua Avenue, Honolulu, Hawaii 96815 Governor ‘N ' ‘ kelepona tel 808 973 2255 7' A U T H O R I T Y kalepa'i fax 808 973 2253 Chris Tatum kahua pa'a web hawaiitourismauthurityorg President and Chief Executive Officer Statement of CHRIS TATUM Hawai‘i Tourism Authority before the SENATE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS Wednesday, April 3, 2019 10:20AM State Capitol, Conference Room #211 In consideration of HOUSE BILL NO 420 HD1 SD1 RELATING TO HAWAIIAN CULTURE. Chair Dela Cruz, Vice Chair Keith-Agaran, and members of the Senate Committee on Ways and Means: The Hawai‘i Tourism Authority (HTA) strongly supports House Bill 420 HD1 SD1, which removes the provision designating the Hawai‘i Convention Center (HCC) as the location for the operation of a Hawaiian center and museum of Hawaiian music and dance. The concept of developing a Hawaiian Center and Museum of Hawaiian Music and Dance is one that we fully support; however, the challenge has been the requirement of locating the center at the Hawai‘i Convention Center. By removing this requirement, we will then be allowed to work with the community to identify the best location for this very important facility. We humbly request your support of this measure. Thank you for the opportunity to offer testimony in support of House Bill 420 HD1 SD1. HB-420-SD-1 Submitted on: 3/29/2019 8:08:03 PM Testimony for WAM on 4/3/2019 10:20:00 AM Testifier Present at Submitted By Organization Position Hearing Kirstin Kahaloa Individual Support No Comments: April 2, 2019 Senator Donovan Dela Cruz, Chair Senator Gilbert Keith-Agaran, Vice Chair Committee on Ways and Means Conference Room 211 Hawai‘i State Capitol Honolulu, HI 96813 RE: Testimony on HB420 HD1 SD1, Relating to Hawaiian Culture Chair Dela Cruz, Vice Chair Keith-Agaran, and Committee Members: My name is Melanie Ide and I am the President and CEO of the Bishop Museum, Hawai‘i’s State Museum of Natural and Cultural History. -

Legislative Testimony Senate Bill No. 1005 RELATING to PUBLICITY

Legislative Testimony Senate Bill No. 1005 RELATING TO PUBLICITY RIGHTS Committee on Economic Development and Technology February 9, 2009 1:15 p.m. Room 016 Aloha Chair Fukunaga, Vice Chair Baker, and Members. OHA strongly supports Senate Bill No. 1005 Relating to Publicity Rights. The purpose of this bill is to help protect in Hawaii the music of Hawaii, and all other works of authorship, by establishing a property right in the commercial use of a person’s name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness. This right is generally called a “right of publicity” and has often been appropriated by promoters and marketers of the music of Hawaii, without the permission of the artists and their heirs, to sell products that are objectionable to the artists and heirs, yet feature the artist’s name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness. The bill is detailed, including provisions relating to transfer of the right, injunctions and damages for infringement of the right, and exemptions for situations where the law would not apply. We believe the bill strikes a reasonable balance between protecting the right and recognizing that the right is not absolute. Mahalo for the opportunity to testify. fukunaga4 - Michelle From: Sen. Carol Fukunaga Sent: Friday, February 06, 2009 3:50 PM To: fukunaga4 - Michelle; Jared Yamanuha Subject: FW: Publicity Rights Bill SN-1005 Attachments: SB1005_.pdf For 2/9/09 hearing testimony ------ Forwarded Message From: Eric Keawe <[email protected]> Date: Thu, 5 Feb 2009 18:47:15 -1000 To: <[email protected]> Cc: Carol Fukunaga <[email protected]>, Rosalyn Baker <[email protected]>, Clayton Hee <[email protected]>, David Ige <[email protected]>, Sam Slom <[email protected]> Subject: Publicity Rights Bill SN-1005 Dear Friends, I would like to share with you information about a “Publicity Rights” Bill now pending in the Legislature. -

Read Liner Notes Here

LINER NOTES Martin Pahinui Ho'olohe One of Hawaiian music‘s most gifted vocalists, John Martin Pahinui has performed with a host of top performers, including his father‘s legendary Gabby Pahinui Hawaiian Band, The Peter Moon Band, The Pahinui Brothers, Nina Kealiçiwahamana, Bill Kaiwa and slack key super group Hui Aloha (with slack key guitarists George Kuo and Dennis Kamakahi). The youngest child of Gabby Pahinui (1921-1980) and Emily Pahinui, Martin grew up surrounded by music— not only the amazing kï höçalu (slack key) in his family home but also the many other styles floating on the wind in Waimänalo, where he grew up and still lives. Like many children of famous musicians, Martin is keenly aware of a double responsibility: to honor his family‘s musical legacy and to always be himself. ―My daddy is a very big influence on all of us,‖ Martin says, ―but he always did things his own way, and he taught us to trust our own instincts too. He loved Hawaiian music but he wasn‘t afraid to change something if he felt it was the right thing to do. Some people would grumble, but he‘d say, ‗So what, some people grumble no matter what you do.‘ He always said to respect the song and the composer and the people who taught you, but never be afraid to express your own feelings when you play.‖ Recently, when the local rap group Sudden Rush asked the Pahinui family for their blessings to use a recording of Gabby‘s classic rendition of Hiçilawe, Martin supported them. -

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project by Gary T. Kubota Copyright © 2018, Stories of Change – Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project The Kokua Hawaii Oral History interviews are the property of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project, and are published with the permission of the interviewees for scholarly and educational purposes as determined by Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. This material shall not be used for commercial purposes without the express written consent of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. With brief quotations and proper attribution, and other uses as permitted under U.S. copyright law are allowed. Otherwise, all rights are reserved. For permission to reproduce any content, please contact Gary T. Kubota at [email protected] or Lawrence Kamakawiwoole at [email protected]. Cover photo: The cover photograph was taken by Ed Greevy at the Hawaii State Capitol in 1971. ISBN 978-0-9799467-2-1 Table of Contents Foreword by Larry Kamakawiwoole ................................... 3 George Cooper. 5 Gov. John Waihee. 9 Edwina Moanikeala Akaka ......................................... 18 Raymond Catania ................................................ 29 Lori Treschuk. 46 Mary Whang Choy ............................................... 52 Clyde Maurice Kalani Ohelo ........................................ 67 Wallace Fukunaga .............................................. -

Louis “Moon” Kauakahi

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2020 | VOL. 39 NO. 6 LOUIS “MOON” KAUAKAHI The former Mākaha Sons band member always backed up his music career with a day job – Page 3 CEO MESSAGE STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chair Leslie Wilcox A Slimmed-Down Joanne Lo Grimes PBS Hawai‘i President and CEO Vice Chair Program Guide Bettina Mehnert Secretary You may notice that this monthly young children to our online PBS Joy Miura Koerte program guide is skinnier than it was KIDS 24/7 channel, which is aligned last month, as if it went on a crash with fun, educational video games. Treasurer Kent Tsukamoto diet. There was indeed a crash of sorts, one that all of us are dealing Folks have been phoning or Muriel Anderson with in one way or another: the writing with kind sentiments Susan Bendon economic fall-out from COVID-19. including: “You’re a lifesaver for Jodi Endo Chai helping me educate my child at James E. Duffy Jr. Matthew Emerson PBS Hawai‘i is part of the local home.” “You bring us delight, Jake Fergus community. When our supporters beauty, wonder and information Jason Fujimoto suffer financial loss, we feel it, too. every day…” “I’m going through Jason Haruki Many people are limiting their a hard time, but I feel better with Ian Kitajima charitable giving. Our heart goes out the inspiration I get from your Noelani Kalipi to those who’ve been hard hit by programs.” Kamani Kuala‘au Theresia McMurdo effects of the pandemic. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga Aloha is real and palpable and Aaron Salā As part of stewarding our feeds heart and soul. -

We're All Hawaiians Now: Kanaka Maoli Performance and the Politics

We’re All Hawaiians Now: Kanaka Maoli Performance and the Politics of Aloha by Stephanie Nohelani Teves A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Vicente M. Diaz, Chair Professor Amy K. Stillman Assistant Professor Evelyn A. Alsultany Associate Professor Sarita See, University of California Davis Associate Professor Andrea Smith, University of California Riverside © Stephanie Nohelani Teves All rights reserved 2012 Dedication For my ‘ohana and Kānaka Maoli everywhere. ii Acknowledgements I did not plan any of this. Six years ago I did not even know what graduate school was or where Michigan even was on a map. I never dreamed of being a scholar, being in academia, or writing a dissertation, but in the words of Jujubee, I’m still here! This was all made possible and at times even enjoyable because of so many people. First and foremost I have to thank my parents and sister for their love and support. Thank you for putting up with me, there really is no other way to put it. And to the performers in this dissertation, Krystilez and Cocoa Chandelier, I hope you know how inspiring you are! Thank you for sharing your time with me and allowing me to write about your brilliant work. Also, to the filmmakers and everyone in the film, Ke Kulana He Māhū, mahalo for being in such an important film. Sorry if I say something that upsets you. Over the past six years, my amazing committee has shown me that you can keep your politics in the academic industrial complex. -

KA WAI OLA the LIVING WATER of OHA

KA WAI OLA THE LIVING WATER of OHA OFFICE of HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS • 711 Kapi‘olani Blvd., Ste. 500 • Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96813-5249 Iune (June) 2008 Leaving Hawai‘i for Los Angeles Vol. 25, No. 6 almost a decade ago to make it big in the music biz, Justin Young now adds his Plotting the Hawaiian soul to future of the stylings of Mauna Kea Colbie Caillat page 04 DHHL resumes work on stalled homes page 06 3 UH law school graduates specialize in Native Hawaiian law page 11 Combating tobacco use with cultural sensitivity page 14 Pacific arts fest! page 23 Leap of Faith page 18 www.oha.org A pensive Justin Young after a Waikïkï performance with Colbie Caillat. Photo: Blaine Fergerstrom. THE OHA MA¯ LAMA LOAN % 5.00 APR ~ LOW FIXED RATE ~ FIXED TERM for 5 YEARS ~ LOAN up to $75,000 PLUS, EARN UP TO The OHA Ma¯lama Loan Program through First Hawaiian Bank is 5,000 CASHPOINTSSM exclusively for Native Hawaiians and Native Hawaiian organizations. It can be used for tuition, home improvement, and any of your ••• When you apply and are business needs. For more information, please call 643-LOAN. To approved for the Priority RewardsSM apply, please visit fhb.com or any First Hawaiian Bank branch. Debit and Credit Cards*. Applicants must be of Native Hawaiian ancestry (birth certifi cate, OHA registry card, or Kamehameha Schools verifi cation letter will be accepted as proof) or a Native Hawaiian organization. If the applicant is a group of people organized for economic development purposes, applicant ownership must be 100% Native Hawaiian. -

Harry's Song List

!"#$%&'!(%)"*%&'+,%-,*)"*./#0,!! Harry!s repertoire consists of literally hundreds of vocal and instrumental selections ranging from traditional Hawaiian, to Classical, to Pop Standards and Contemporary tunes covering the 1950!s to the present. Below are just a few examples of his diversity and range. 50 Years of Rock n Roll All My Loving, Blackbird, Good Day Sunshine, I Feel Fine, Lucy in the Sky, Paperback Writer, Something, The Long and Winding Road, Hooked on a Feeling, Lay Lady Lay, Like a Rolling Stone, Who'll Stop the Rain, Teach Your Children, I Can See Clearly Now, Mr. Bojangles, Crazy, A Whiter Shade of Pale, The Sound of Silence, Mustang Sally, In My Room, Mr. Tamborine Man, Horse With No Name, Here Comes the Sun, Norwegian Wood, Can't Find My Way Home, No Woman No Cry, Redemption Song, Waiting in Vain, Moonshadow, Wild World, Our House, Ziggy Stardust, Desperado, Lyin' Eyes, Take It Easy, Tequila Sunrise, Wonderful Tonight, Landslide, Some Kind of Wonderful, Doctor My Eyes, Fire & Rain, Up on the Roof, Time in a Bottle, Angel, Little Wing, The Wind Cries Mary, Imagine, Dust in the Wind, Stairway to Heaven, Nights in White Satin, Heart of Gold, Old Man, Sitting on the Dock of the Bay, Bluebird, Baby I Love Your Way, Wish You Were Here, Sailing, Paint it Black, Wild Horses, Brown Eyed Girl, Hard Luck Woman, My Love, Street of Dreams, Now & Forever, Life by the Drop, Roxanne, I Won't Back Down, Into the Great Wide Open, Kryptonite, Change the World, Tears in Heaven, Out of My Head, Time of Your Life, Runaway Train, Fields of -

Section Viii

Dancing Cat Records Hawaiian Slack Key Information Booklet, SECTION VIII: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND ADDENDUM 1. For information about the tuning of a song that is not listed, or any other questions, you can e-mail Dancing Cat at [email protected], or write to Dancing Cat Productions, P.O. Box 4287, Santa Cruz, California, USA, 95063, attn: Dept. SKQ, and we will try to help. 2. Dancing Cat Records plans to produce more solo guitar based Slack Key recordings of the late Sonny Chillingworth, Ray Kane, the late Leonard Kwan, Keola Beamer, Led Kaapana, Cyril Pahinui, George Kuo, Ozzie Kotani, Bla Pahinui, Martin Pahinui, George Kahumoku, Jr., Moses Kahumoku, Cindy Combs, Malaki Kanahele, and Patrick Cockett, and others. Also planned are more recordings of pure duets of Slack Key guitar with acoustic steel guitar, including the late Barney Isaacs playing acoustic steel guitar duets with Slack Key guitarists George Kuo, Led Kaapana, and Cyril Pahinui; and Bob Brozman on acoustic steel with Led Kaapana and with Cyril Pahinui. 3. Mahalo nui loa (special thanks) to the following people who contributed in many various ways to make this information booklet possible: Leimomi Akana, Carlos Andrade, Haunani Apoliona, Kapono Beamer, Keola & Moanalani Beamer, Nona Beamer, Kapono Beamer, Reggie Berdon, Milan Bertosa, the late Lawrence Brown, Bob Brozman, Kiki Carmillos, Walter Carvalho, the late Sonny Chillingworth, Mahina Chillingworth, Patrick Cockett, Cindy Combs, Michael Cord, Jack DeMello, Jon DeMello, Cathy Econom, Ken Emerson, Heather Gray, the late Dave Guard, Gretchen Guard, Gary Haleamau, Uluwehi Guerrero, Keith Haugen, Tony & Robyn Hugar, the late Leland “Atta” Isaacs, Jr., the late Barney Isaacs & Cookie Isaacs, Barney Boy Isaacs, the late Winola Isaacs, Wayne Jacintho, Howard Johnston, J. -

Ka Wai Ola O

OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS/BISHOP ESTATE REQUESTS FOR 1989-1990 ADMISSION APPLICATIONS ARE BEING ACCEPTED APPLICATION DEADLINES ARE AS FOLLOWS: Kindergarten .................................. November 18, 1988 Grades 7,8,9,10,11 and 12 ...................... December 16,1988 Vol. 5, No. 10 "The Living Water of OHA" Okakopa (October) 1988 Preschools* ................. .................... January 27,1989 Applications are not being taken for grades 1,2,3,4,5 and 6. *Preschool enrollments are restricted to children who live in the follow- ing communities: Anahola, Kaua'i; Waihe'e, Maui' Wai'anae, O'ahu; Ko'olau Loa, O'ahu; Kalihi/Palama, O'ahu. • Public information meetings will be held at the following places and times: ISLAND PLACE DATE GRADE K GRADE 7-12 O'ahu Kailua Public Library Oct. 19 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Pearl City Reg ional Lib. Oct. 20 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Hulihee Aiea Public Library Oct. 24 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Wahiawa Recreation Center Oct. 25 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Kaneohe Regional Library Oct. 26 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Ewa Beach Comm. School Lib. Oct. 27 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Palace Kahuku Comm. School Lib. Nov. 1 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Waimanalo Comm. School Lib. Nov. 2 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Waianae Public Library Nov. 7 6-7 p.m. 7:30-9 p.m. Waikiki/Kapahulu Library Nov. 9 6-7 p.m. -

[ADD in the Ording Info---HARRY's MUSIC INFO HERE and INFO

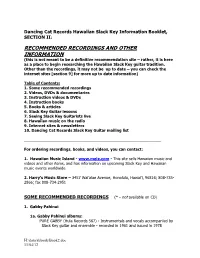

Dancing Cat Records Hawaiian Slack Key Information Booklet, SECTION II: RECOMMENDED RECORDINGS AND OTHER INFORMATION (this is not meant to be a definitive recommendation site – rather, it is here as a place to begin researching the Hawaiian Slack Key guitar tradition. Other than the recordings, it may not be up to date – you can check the internet sites [section 9] for more up to date information) Table of Contents: 1. Some recommended recordings 2. Videos, DVDs & documentaries 3. Instruction videos & DVDs 4. Instruction books 5. Books & articles 6. Slack Key Guitar lessons 7. Seeing Slack Key Guitarists live 8. Hawaiian music on the radio 9. Internet sites & newsletters 10. Dancing Cat Records Slack Key Guitar mailing list ________________________________________________________________ For ordering recordings, books, and videos, you can contact: 1. Hawaiian Music Island - www.mele.com - This site sells Hawaiian music and videos and other items, and has information on upcoming Slack Key and Hawaiian music events worldwide 2. Harry’s Music Store – 3457 Wai’alae Avenue, Honolulu, Hawai’i, 96816; 808-735- 2866; fax 808-734-2951 SOME RECOMMENDED RECORDINGS (* - not available on CD) 1. Gabby Pahinui 1a. Gabby Pahinui albums: PURE GABBY (Hula Records 567) - Instrumentals and vocals accompanied by Slack Key guitar and ensemble - recorded in 1961 and issued in 1978 H:/data/skbook/Book2.doc 11/04/12 HAWAIIAN SLACK KEY, VOLUME 1-WITH GABBY PAHINUI (Waikiki Records 319) – Instrumentals and vocals accompanied by Slack Key guitar and ensemble - 1960