Bad Girls Graspcord Andpu[[ .Fromwrapper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Painters William J. Simmons December 2015

BY WILLIAM J. SIMMONS TRUE PORTRAIT BY KRISTINE LARSEN TO FORM DEBORAH KASS SHAKES UP THE CANON 60 MODERN PAINTERS DECEMBER 2015 BLOUINARTINFO.COM FORM DEBORAH KASS SHAKES UP Deborah Kass in her Brooklyn THE CANON studio, 2015. BLOUINARTINFO.COM DECEMBER 2015 MODERN PAINTERS 61 intensity of her social and art historical themes. The result is a set of tall, sobering, black-and-blue canvases adorned with “THE ONLY ART THAT MATTERS equally hefty neon lettering, akin, perhaps, to macabre monuments or even something more sinister in the tradition of IS ABOUT THE WORLD. pulp horror movies. This is less a departure than a fearless statement that affirms and illuminates her entire oeuvre—a tiny retrospective, perhaps. Fueled by an affinity for the medium AUDRE LORDE SAID IT. TONI and its emotive and intellectual possibilities, Kass has created a template for a disruptive artistic intervention into age-old MORRISON SAID IT. EMILY aesthetic discourses. As she almost gleefully laments, “All these things I do are things that people denigrate. Show tunes— so bourgeois. Formalism—so retardataire. Nostalgia—not a real DICKINSON SAID IT. I’M emotion. I want a massive, fucked-up, ‘you’re not sure what it means but you know it’s problematic’ work of art.” At the core of INTERESTED IN THE WORLD.” Kass’s practice is a defiant rejection of traditional notions of taste. For example, what of Kass’s relationship to feminism, queer- Deborah Kass is taking stock—a moment of reflection on what ness, and painting? She is, for many, a pioneer in addressing motivates her work, coincidentally taking place in her issues of gender and sexuality; still, the artist herself is ambivalent Gowanus studio the day before the first Republican presidential about such claims, as is her right. -

Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy Bad Girls: Agency, Revenge, and Redemption in Contemporary Drama Courtney Watson, Ph.D. Radford University Roanoke, Virginia, United States [email protected] ABSTRACT Cultural movements including #TimesUp and #MeToo have contributed momentum to the demand for and development of smart, justified female criminal characters in contemporary television drama. These women are representations of shifting power dynamics, and they possess agency as they channel their desires and fury into success, redemption, and revenge. Building on works including Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, dramas produced since 2016—including The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, and Killing Eve—have featured the rise of women who use rule-breaking, rebellion, and crime to enact positive change. Keywords: #TimesUp, #MeToo, crime, television, drama, power, Margaret Atwood, revenge, Gone Girl, Orange is the New Black, The Handmaid’s Tale, Ozark, Killing Eve Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 37 Watson From the recent popularity of the anti-heroine in novels and films like Gone Girl to the treatment of complicit women and crime-as-rebellion in Hulu’s adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale to the cultural watershed moments of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, there has been a groundswell of support for women seeking justice both within and outside the law. Behavior that once may have been dismissed as madness or instability—Beyoncé laughing wildly while swinging a baseball bat in her revenge-fantasy music video “Hold Up” in the wake of Jay-Z’s indiscretions comes to mind—can be examined with new understanding. -

Jude Akuwudike

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Jude Akuwudike Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Role Director Production Company Delroy Grant (The Night MANHUNT Marc Evans ITV Studios Stalker) PLEBS Agrippa Sam Leifer Rise Films/ITV2 MOVING ON Dr Bello Jodhi May LA Productions/BBC THE FORGIVING EARTH Dr Busasa Hugo Blick BBC/Netflix CAROL AND VINNIE Ernie Dan Zeff BBC IN THE LONG RUN Uncle Akie Declan Lowney Sky KIRI Reverend Lipede Euros Lyn Hulu/Channel 4 THE A WORD Vincent Sue Tully Fifty Fathoms/BBC DEATH IN PARADISE Series 6 Tony Simon Delaney Red Planet/BBC CHEWING GUM Series 2 Alex Simon Neal Retort/E4 FRIDAY NIGHT DINNER Series 4 Custody Sergeant Martin Dennis Channel 4 FORTITUDE Series 2 & 3 Doctor Adebimpe Hettie Macdonald Tiger Aspect/Sky Atlantic LUCKY MAN Doctor Marghai Brian Kelly Carnival Films/Sky 1 UNDERCOVER Al James Hawes BBC CUCUMBER Ralph Alice Troughton Channel 4 LAW & ORDER: UK Marcus Wright Andy Goddard Kudos Productions HOLBY CITY Marvin Stewart Fraser Macdonald BBC Between Us (pty) Ltd/Precious THE NO.1 LADIES DETECTIVE AGENCY Oswald Ranta Charles Sturridge Films MOSES JONES Matthias Michael Offer BBC SILENT WITNESS Series 11 Willi Brendan Maher BBC BAD GIRLS Series 7 Leroy Julian Holmes Shed Productions for ITV THE LAST DETECTIVE Series 3 Lemford Bradshaw David Tucker Granada HOLBY CITY Derek Fletcher BBC ULTIMATE FORCE Series 2 Mr Salmon ITV SILENT WITNESS: RUNNING ON -

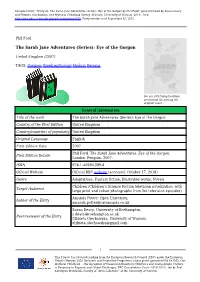

OMC | Data Export

Amanda Potter, "Entry on: The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon by Phil Ford", peer-reviewed by Susan Deacy and Elżbieta Olechowska. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/550. Entry version as of September 25, 2021. Phil Ford The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon United Kingdom (2007) TAGS: Gorgons Greek mythology Medusa Perseus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work The Sarah Jane Adventures (Series): Eye of the Gorgon Country of the First Edition United Kingdom Country/countries of popularity United Kingdom Original Language English First Edition Date 2007 Phil Ford. The Sarah Jane Adventures: Eye of the Gorgon. First Edition Details London: Penguin, 2007. ISBN 978-1-40590-399-8 Official Website Official BBC website (accessed: October 17, 2018) Genre Adaptations, Fantasy fiction, Illustrated works, Novels Children (Children’s Science Fiction television novelization, with Target Audience large print and colour photographs from the television episodes) Amanda Potter, Open University, Author of the Entry [email protected] Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, [email protected] Peer-reviewer of the Entry Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. -

UC Merced UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal

UC Merced UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal Title Gender, Sexuality, and Inter-Generational Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29q2t238 Journal UC Merced Undergraduate Research Journal, 8(2) Author Abidia, Layla Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/M482030778 Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Gender, Sexuality, and Inter-Generational Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Layla Abidia University of California, Merced Author Notes: Questions and comments can be address to [email protected] 1 Differences in Hmong and Hmong Americans Abstract Hmong American men and women face social and cultural struggles where they are expected to adhere to Hmong requirements of gender handed down to them by their parents, and the expectations of the country they were born in. The consequence of these two expectations of contrasting values results in stress for everyone involved. Hmong parents are stressed from not having a secure hold on their children in a foreign environment, with no guarantee that their children will follow a “traditional” route. Hmong American men are stressed from growing up in a home environment that grooms them to be a focal point of familial attention based on gender, with the expectation that they will eventually be responsible for an entire family; meanwhile, they are living in this American national environment that stresses that the ideal is that gender is irrelevant in the modern world. Hmong American women are stressed and in turn hold feelings of resentment that they are expected to adhere to traditional familial roles by their parents in addition to following a path to financial success the same as men. -

THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’S Original Love Story by David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin

PRESS RELEASE IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE Twitter | @ModerateSoprano Facebook | @TheModerateSoprano Website | www.themoderatesoprano.com Playful Productions presents Hampstead Theatre’s THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’s Original Love Story By David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin LAST CHANCE TO SEE DAVID HARE’S THE MODERATE SOPRANO AS CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED WEST END PRODUCTION ENTERS ITS FINAL FIVE WEEKS AT THE DUKE OF YORK’S THEATRE. STARRING OLIVIER AWARD WINNING ROGER ALLAM AND NANCY CARROLL AS GLYNDEBOURNE FOUNDER JOHN CHRISTIE AND HIS WIFE AUDREY MILDMAY. STRICTLY LIMITED RUN MUST END SATURDAY 30 JUNE. Audiences have just five weeks left to see David Hare’s critically acclaimed new play The Moderate Soprano, about the love story at the heart of the foundation of Glyndebourne, directed by Jeremy Herrin and starring Olivier Award winners Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll. The production enters its final weeks at the Duke of York’s Theatre where it must end a strictly limited season on Saturday 30 June. The previously untold story of an English eccentric, a young soprano and three refugees from Germany who together established Glyndebourne, one of England’s best loved cultural institutions, has garnered public and critical acclaim alike. The production has been embraced by the Christie family who continue to be involved with the running of Glyndebourne, 84 years after its launch. Executive Director Gus Christie attended the West End opening with his family and praised the portrayal of his grandfather John Christie who founded one of the most successful opera houses in the world. First seen in a sold out run at Hampstead Theatre in 2015, the new production opened in the West End this spring, with Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll reprising their original roles as Glyndebourne founder John Christie and soprano Audrey Mildmay. -

Bad Girls to the Rescue an Exhibition of Feminist Art from the 1990S Has Much to Teach Us Today

PERSPECTIVES Bad Girls to the Rescue An exhibition of feminist art from the 1990s has much to teach us today By Maura Reilly n my new book Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics did just that—and within a lineage worth revisiting as the present of Curating (Thames & Hudson), I devoted a chapter to adjusts for oversights of the past. I exhibitions that have lingered in the historical record for their Though most commonly associated with a notorious run at the commitment to “Resisting Masculinism and Sexism.” As what New Museum in 1994—in a tradition that would directly influence constitutes sexual prejudice continues to evolve, it’s imperative “Trigger” decades later—the first iteration of a series of shows titled that curators continually query and challenge the gender norms “Bad Girls” was organized separately the year before for the Institute by which we are all confined. “Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a of Contemporary Arts in London (followed by a presentation at the Weapon,” a recent exhibition at the New Museum in New York, Centre for Contemporary Arts in Glasgow). Curated by Kate Bush, NEW YORK. ART, NEW MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY FRED SCRUTON/COURTESY THIS PAGE: RIGHTS SOCIETY/ARS ARTIST OPPOSITE: ©DEBORAH KASS/PHOTO COURTESY 32 ARTNEWS Perspectives.indd 1 2/16/18 5:12 PM Emma Dexter, and Nicola White, the exhibition celebrated a new spirit of playfulness, tactility, and perverse humor in the work of six British and American women artists: Helen Chadwick, Dorothy Cross, Nicole Eisenman, Rachel Evans, Nan Goldin, and Sue Williams—each of whom was represented by several works. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

REALLY BAD GIRLS of the BIBLE the Contemporary Story in Each Chapter Is Fiction

Higg_9781601428615_xp_all_r1_MASTER.template5.5x8.25 5/16/16 9:03 AM Page i Praise for the Bad Girls of the Bible series “Liz Curtis Higgs’s unique use of fiction combined with Scripture and modern application helped me see myself, my past, and my future in a whole new light. A stunning, awesome book.” —R OBIN LEE HATCHER author of Whispers from Yesterday “In her creative, fun-loving way, Liz retells the stories of the Bible. She deliv - ers a knock-out punch of conviction as she clearly illustrates the lessons of Scripture.” —L ORNA DUECK former co-host of 100 Huntley Street “The opening was a page-turner. I know that women are going to read this and look at these women of the Bible with fresh eyes.” —D EE BRESTIN author of The Friendships of Women “This book is a ‘good read’ directed straight at the ‘bad girl’ in all of us.” —E LISA MORGAN president emerita, MOPS International “With a skillful pen and engaging candor Liz paints pictures of modern sit u ations, then uniquely parallels them with the Bible’s ‘bad girls.’ She doesn’t condemn, but rather encourages and equips her readers to become godly women, regardless of the past.” —M ARY HUNT author of Mary Hunt’s Debt-Proof Living Higg_9781601428615_xp_all_r1_MASTER.template5.5x8.25 5/16/16 9:03 AM Page ii “Bad Girls is more than an entertaining romp through fascinating charac - ters. It is a bona fide Bible study in which women (and men!) will see them - selves revealed and restored through the matchless and amazing grace of God.” —A NGELA ELWELL HUNT author of The Immortal “Liz had me from the first paragraph. -

Convent Slave Laundries? Magdalen Asylums in Australia

Convent slave laundries? Magdalen asylums in Australia James Franklin* A staple of extreme Protestant propaganda in the first half of the twentieth century was the accusation of ‘convent slave laundries’. Anti-Catholic organs like The Watchman and The Rock regularly alleged extremely harsh conditions in Roman Catholic convent laundries and reported stories of abductions into them and escapes from them.1 In Ireland, the scandal of Magdalen laundries has been the subject of extensive official inquiries.2 Allegations of widespread near-slave conditions and harsh punishments turned out to be substantially true.3 The Irish state has apologized,4 memoirs have been written, compensation paid, a movie made.5 Something similar occurred in England.6 1 ‘Attack on convents’, Argus 21/1/1907, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/10610696; ‘Abbotsford convent again: another girl abducted’, The Watchman 22/7/1915, http:// trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/111806210; ‘Protestant Federation: Why it is needed: Charge of slavery in convents’, Maitland Daily Mercury 23/4/1921, http://trove.nla.gov. au/ndp/del/article/123726627; ‘Founder of “The Rock” at U.P.A. rally’, Northern Star 2/4/1947, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/99154812. 2 Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (Ireland, 2009), ch. 18, http://www. childabusecommission.ie/rpt/pdfs/CICA-VOL3-18.pdf; Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalen Laundries (McAleese Report, 2013), http://www.justice.ie/en/ JELR/Pages/MagdalenRpt2013; summary at http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/05/magdalene-laundries-ireland-state- guilt 3 J.M. -

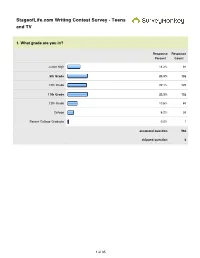

Stageoflife.Com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV

StageofLife.com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV 1. What grade are you in? Response Response Percent Count Junior High 14.3% 81 9th Grade 23.3% 132 10th Grade 22.1% 125 11th Grade 23.3% 132 12th Grade 10.6% 60 College 6.2% 35 Recent College Graduate 0.2% 1 answered question 566 skipped question 0 1 of 35 2. How many TV shows (30 - 60 minutes) do you watch in an average week during the school year? Response Response Percent Count 20+ (approx 3 shows per day) 21.7% 123 14 (approx 2 shows per day) 11.3% 64 10 (approx 1.5 shows per day) 9.0% 51 7 (approx. 1 show per day) 15.7% 89 3 (approx. 1 show every other 25.8% 146 day) 1 (you watch one show a week) 14.5% 82 0 (you never watch TV) 1.9% 11 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3. Do you watch TV before you leave for school in the morning? Response Response Percent Count Yes 15.7% 89 No 84.3% 477 answered question 566 skipped question 0 2 of 35 4. Do you have a TV in your bedroom? Response Response Percent Count Yes 38.7% 219 No 61.3% 347 answered question 566 skipped question 0 5. Do you watch TV with your parents? Response Response Percent Count Yes 60.6% 343 No 39.4% 223 If yes, which show(s) do you watch as a family? 302 answered question 566 skipped question 0 6. Overall, do you think TV is too violent? Response Response Percent Count Yes 28.3% 160 No 71.7% 406 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3 of 35 7. -

Claytime! Ceramics Finds Its Place in the Art-World Mainstream by Lilly Wei POSTED 01/15/14

Claytime! Ceramics Finds Its Place in the Art-World Mainstream BY Lilly Wei POSTED 01/15/14 Versatile, sensuous, malleable, as basic as mud and as old as art itself, clay is increasingly emerging as a material of choice for a wide range of contemporary artists Ceramic art, referring specifically to American ceramic art, has finally come out of the closet, kicking and disentangling itself from domestic servitude and minor- arts status—perhaps for good. Over the past year, New York has seen, in major venues, a spate of clay-based art. There was the much-lauded Ken Price retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as his exhibitions atFranklin Parrasch Gallery and the Drawing Center. Once known as a ceramist, Price is now considered a sculptor, one who has contributed significantly to the perception of ceramics as fine art. Ann Agee’s installation Super Imposition (2010), at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, presents the artist’s factory-like castings of rococo-style vessels in a re-created period room. COURTESY PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART At David Zwirner gallery, there was a show of early works by Robert Arneson, a founder of California Funk, who arrived on the scene before Paul McCarthy did. “VESSELS” at the Horticultural Society of New York last summer, with five cross- generational artists ranging from Beverly Semmes to Francesca DiMattio, provided a focused and gratifying challenge to ceramic orthodoxies. Currently, an international show on clay, “Body & Soul: New International Ceramics,” is on view at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York (up through March 2), featuring figurative sculptures with socio-political themes by such artists as Michel Gouéry, Mounir Fatmi, and Sana Musasama.