Relationship Scope and Cooperation in Interfirm Relationships: Evidence from Airlines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

PSA Airlines CASE STUDY

PSA Airlines CASE STUDY PSA Airlines PSA Airlines’ headquarters was originally estab- lished in Dayton in 1985 while it was under the ownership of Piedmont Airlines. Dayton remains headquarters to PSA Airlines, now a wholly owned subsidiary of US Airways, that merged with American Airlines in 2013. The airline operates an all-jet fleet and is considered the fastest- growing regional carrier under the American Eagle brand with nearly 3,000 employees operating nearly 700 daily flights to nearly 90 destinations. Since 2014, PSA has doubled its size and, by 2016, operated 150 Bombardier CRJ 900 aircraft. As a result of this growth, PSA has expanded its Dayton-based facilities, including a new maintenance hangar that opened in October of 2016. The new, 77,000 square foot hangar is adjacent to PSA’s existing 40,000 square foot operations control center and 6,500 professional learning center located at the Dayton International Airport and is the airline’s largest aircraft maintenance support facility. Dion Flannery, PSA President, stated that the new hanger is…“a testament to our growth, it’s an important infrastructure for us that’s going to last the rest of our days here.” How the City of Dayton (City) and its local partner, Montgomery County Economic Development Services (MCDS) helped PSA Airlines achieve speed-to-market, lower costs, and reduce risk: SPEED TO MARKET: In 2014, when PSA was planning to receive 30 new Bombardier CRJ 900 aircraft, the airline needed maintenance facilities for the new aircraft. The City of Dayton presented a schedule that met PSA’s and its parent company’s schedule through a 20-year lease customized to PSA’s needs. -

General Files Series, 1932-75

GENERAL FILE SERIES Table of Contents Subseries Box Numbers Subseries Box Numbers Annual Files Annual Files 1933-36 1-3 1957 82-91 1937 3-4 1958 91-100 1938 4-5 1959 100-110 1939 5-7 1960 110-120 1940 7-9 1961 120-130 1941 9-10 1962 130-140 1942-43 10 1963 140-150 1946 10 1964 150-160 1947 11 1965 160-168 1948 11-12 1966 168-175 1949 13-23 1967 176-185 1950-53 24-53 Social File 186-201 1954 54-63 Subject File 202-238 1955 64-76 Foreign File 239-255 1956 76-82 Special File 255-263 JACQUELINE COCHRAN PAPERS GENERAL FILES SERIES CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents Subseries I: Annual Files Sub-subseries 1: 1933-36 Files 1 Correspondence (Misc. planes) (1)(2) [Miscellaneous Correspondence 1933-36] [memo re JC’s crash at Indianapolis] [Financial Records 1934-35] (1)-(10) [maintenance of JC’s airplanes; arrangements for London - Melbourne race] Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1934 (1)-(7) 2 Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1935 (1)(2) Edmund Jakobi 1934 Re: G.B. Plane Return from England Just, G.W. 1934 Leonard, Royal (Harlan Hull) 1934 London Flight - General (1)-(12) London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables General (1)-(5) [cable file of Royal Leonard, FBO’s London agent, re preparations for race] 3 London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Fueling Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Hangar Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Insurance [London - Melbourne Flight Instructions] (1)(2) McLeod, Fred B. [Fred McLeod Correspondence July - August 1934] (1)-(3) Joseph B. -

November 2015 Newsletter

PilotsPROUDLY For C ELEBRATINGKids Organization 32 YEARS! Pilots For KidsSM ORGANIZATION Helping Hospitalized Children Since 1983 Want to join in this year’s holiday visits? Newsletter November 2015 See pages 8-9 to contact the coordinator in your area! PFK volunteers from ORF made their first visit to the Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters (CHKD). This group from Delta/VFC-12 and UAL enjoyed their inaugural visit in October and volunteers plan more visits through the holiday season. “100% of our donations go to the kids” visit us at: pilotsforkids.org (2) (3) Pilots For Kids Organization Pilots For Kids Organization President’s Corner... More Success for Dear Members, MCO Golf According to Webster’s Dictionary, the Captain Baldy was joined by an enthusiastic group of definition of fortunate is “bringing some good not golfers at Rio Pinar Country Club in Orlando on Sat- foreseen.” urday, October 24th. The golf event was followed by lunch and a silent auction that raised additional funds Considering that definition, our organization for Orlando area children. is indeed fortunate on many levels. We are fortu- nate to have members who passionately support Special thanks to all of the businesses who donated our vision, financially support our work, and vol- to make the auction a huge success. The group of unteer their valuable time to benefit hospitalized generous doners included the Orlando Magic, Jet- children. Blue, Flight Safety, SeaWorld/Aquatica, i-FLY, Embassy Suites, Hyatt Regency, Wingate, Double- Because of this good fortune, we stand out tree, Renaissance, Sonesta Suites, LaQuinta, the among many creditable charitable organizations. -

AVIATION COMPETITION Issues Related to the Proposed United Airlines-US Airways Merger

United States General Accounting Office GAO Report to Congressional Requesters December 2000 AVIATION COMPETITION Issues Related to the Proposed United Airlines-US Airways Merger GAO-01-212 Printed copies of this document will be available shortly. P U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1991-523-762 GAO Form 171 Rev. (3/99) Contents Page Letter 3 Appendixes I Scope and Methodology 26 II Combined Domestic and International Measures of Airline Size 30 III Selected Financial Data for Some Major U.S. Airlines, Calendar Year 1999 and First 9 Months, 2000 31 IV Markets in Which the Proposed Merger Could Reduce Competition to Only One or Two Competing Airlines 32 V Markets in Which the Proposed Merger Could Increase Competition 41 VI GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 45 Figures 1 New United Would Carry Over One-Quarter of All U.S. Passengers 5 2 Map of Domestic Routes Scheduled to Be Flown by New United 7 3 Number of Markets and Passengers Subject to a Loss of Competition Due to the Merger 13 4 Number of Markets and Passengers That Could Benefit From an Increase in Competition 18 Tables 1 1 Measures of Airline Size for the 12 Months Ending June 30, 2000 10 2 Five Largest Markets in Which the Proposed Merger Could Leave Only Two Competitors 14 3 Number and Size of Markets Dominated by Domestic Airlines 15 4 Market Shares of Nonstop Passenger Traffic Between United’s and US Airways’ Hubs 16 5 Analysis of Markets That Would Receive Online Service From New United 19 6 Comparison of Potential Competitive Impact of the Proposed United-US Airways Merger and the Proposed Northwest--Continental Stock Acquisition and Alliance 21 7 DC Air’s Proposed and Other Airlines’ Scheduled Service From Reagan National to Nine Competed Markets 23 8 DC Air’s Proposed Service Faces Significant Challenges Against Other Airlines in the Washington, D.C., Area 24 Related GAO Products Abbreviations DOJ Department of Justice DOT Department of Transportation GAO General Accounting Office 2 United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 December 15, 2000 The Honorable James L. -

March Newsletter 2014

ISA+21 International Society of Women Airline Pilots March 2014 ISA+21 Chairwoman Nancy “N2” Novaes reports: Mary Ana Gilbert designed our We have just concluded another fabulous WAI Conference. New new banner, member signups have brought our membership to renewed heights; above, to our Scholarship awards were significant, generous and heartfelt. Best generate of all, the professional “face” of ISA+21’s new booth underscored our interest and importance for women airline pilots and women seeking entry into our excitement in field. New banners, new booth setup and an updated logo polished our our organization image and drew crowds. But don’t let me “blow” the good news at Women in reported elsewhere in this newsletter! Suffice it for me to say that Aviation. Membership, Scholarship and WAI are ISA’s “Stars of March.” So read on….. New Members: 2, 13 Ask Amelia: 3-4 It’s a Woman’s World: 5-6 Moscow Conference: 7 Member News: 8-9 In Memory of: 11-12 Scholarship Winners: 14 Emily Warner Howell Honored: 10 Women in Aviation: 15-16 !1 ISA+21 International Society of Women Airline Pilots March 2014 How do you spell Success? Can you say 300? ISA$Welcomes$49$New$Members$ January$15$–$March$15,$2014$ And$a$big$“Welcome$Back”$to$all$our$returning$members.$$$ $$$We$are$glad$to$have$you$with$us$again…304$and$sKll$climbing!$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ Melinda$Albert$ Moraim$Egurbida$Maldonado$$ Devan$Norris$ Kama$Arseneaux$ Margaret$Eickhoff$ Gretchen$Palmer$ Pamela$Barber$ Kimberly$Ewing$ Beth$Phelps$ Valerie$Barre_$ Lindsey$Glasow$ Louise$Pole$ Chriselda$Beltran$ -

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS July, 1988

July, 1988 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS We're Building An Airline From The Ground Up. or more than 80 years, UPS has been the leader in small parcel delivery. [. \ Now, as we climb to the top in the air, we have many aviation oppor tunities for women. To find out more about these outstanding oppor tunitiesF for women pilots, please send your resume to: United Parcel Service, P.O. Box 24265, Louisville, KY 40224 Attn: Air Employment. Wfe are an equal opportunity employer m/f. BARBARA SESTITO r n e Politics and fun do mix From the very first meeting, there were bantering and discussion she said, “ I hope Secretary: Doris Abbate disagreements. The minutes of meetings you don’t take this personally.” Treasurer: Pat Forbes held in early 1930 chronicle the discussions “ Never,” I said. of our strong - willed and independent Nothing we do is so earth shattering as to The election of Gene Nora Jessen as your predecessors. For the ensuing 51 years, we lose a friend over. We can disagree without new international president culminates her have pretty much carried on their tradition. being disagreeable, and we can usually find long career of service to the Ninety-Nines. Our members are still strong - willed, in some middle ground on which we can both Gene Nora has served on the board of dependent and opinionated on almost any operate. directors for a total of 10 years, and has subject. The important thing to remember is that held every office. I have enjoyed working A very good friend called, basically to let we need to spend more time doing fun with her throughout. -

Air Line Pilot Highlights from ALPA’S Page 26 Official Journal of the Air Line Pilots Air Safety Forum Association, International

October 2016 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: » Health Watch page 41 » The Landing page 45 » Our Stories page 42 Air Line PilOt Highlights from ALPA’s Page 26 Official Journal of the Air Line Pilots Air Safety Forum Association, International State of the North American Passenger Airline Industry And What’s on the Horizon Page 19 An Update on ALPA’s Strategic Plan Page 34 Follow us on Twitter PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. @wearealpa For ALPA members: Sophisticated portfolio management, automated. Researching, choosing, and managing your investments is time-consuming. Schwab Intelligent PortfoliosTM does the work for you, with no advisory fees, account service fees, or commissions. Just answer 12 straightforward questions about your investment goals, attitude toward risk, and investment timeline, and Schwab Intelligent Portfolios recommends a portfolio. Schwab Intelligent Portfolios technology: • Provides sophisticated investment advice, building an ETF portfolio of up to 20 asset classes • Helps you set, track, and work toward your savings and income goals • Doesn’t charge account service fees, advisory fees, or commissions • Automatically monitors and rebalances your portfolio You’ll have access to Schwab investment professionals 24/7. And our simple online enrollment means you can begin in minutes. Get invested with as little as $5,000. Get started with Schwab Intelligent Portfolios today at intelligent.schwab.com. For more information, call 1-703-689-2270. Brokerage Products: Not FDIC-Insured • No Bank Guarantee • May Lose Value Schwab investment professionals are employees of Charles Schwab & Co., Inc. The Charles Schwab Corporation provides a full range of securities, brokerage, banking, money management, and financial advisory services through its operating subsidiaries. -

Airport Irregular Operations (Irops) Plan

AIRPORT IRREGULAR OPERATIONS (IROPS) PLAN South Bend International Airport (SBN) St. Joseph County Airport Authority IRREGULAR OPERATIONS PLAN South Bend International Airport TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 3 AIRPORT INFORMATION .............................................................................................. 3 CONTACT INFORMATION ............................................................................................ 4 PASSENGER DEPLANEMENT FOLLOWING EXCESSIVE TARMAC DELAYS ......... 5 USE OF FACILITIES OR GATES IN AN EMERGENCY ................................................ 6 INTERNATIONAL PASSENGER ACCOMMODATIONS ............................................... 6 PUBLIC ACCESS TO THE PLAN .................................................................................. 6 EXHIBIT 1: CONTACT INFORMATION ........................................................................ 7 EXHIBIT 2: TERMINAL GATE USAGE AND LIMITATIONS ........................................ 8 EXHIBIT 3: EQUIPMENT AVAILABILITY AND LIMITATIONS .................................. 10 EXHIBIT 4: TERMINAL DIVERSION OVERFLOW PARKING MAP ........................... 11 EXHIBIT 5: SPECIAL EVENT OVERFLOW PARKING MAP ..................................... 12 EXHIBIT 6: FAR PART 77 IMAGINARY SURFACE MAPS ....................................... -

This Is the Us Master Pilot Scablist the Unionist's Edition

THIS IS THE US MASTER PILOT SCABLIST THE UNIONIST’S EDITION A SCAB is A Person Who is Doing What You’d be Doing if You Weren’t on Strike. A SCAB takes your job, a Job he could not get under normal circumstances. He can only advance himself by taking advantage of labor disputes and walking over the backs of workers trying to maintain decent wages and working conditions. He helps management to destroy his and your profession, often ending up under conditions he/she wouldn't even have scabbed for. No matter. A SCAB doesn't think long term, nor does he think of anything other then himself. His smile shows fangs that drip with your blood, for he willingly destroys families, lives, careers, opportunities and professions at the drop of a hat. He takes from a striker what he knows he could never earn by his own merit: a decent Job. He steals that which others earned at the bargaining table through blood, sweat and tears, and throws it away in an instant - ruining lives, jobs and careers. ONCE A SCAB, ALWAYS A SCAB - NEVER FORGET! Below are brief notes about legal strikes by organized pilots. 1. Century Airlines 1932: Pilots struck to resist wage reduction by E.L Cord, the patron saint of Frank Lorenzo. 2. TWA 1946: Pilots struck over pay on faster 4 engine aircraft, limited by the provisions of Decision 83. 3. National Airlines 1948: Strike over aircraft safety and repeated violations of the labor contract. 4. Western Airlines 1958: Qualifications of the Flight Engineer. -

FY19 Domestic & International Code Share List.Pdf

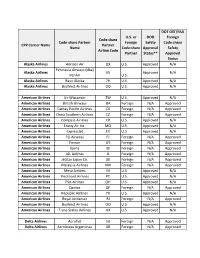

DOT OST/FAA U.S. or DOD Foreign Code-share Code-share Partner Foreign Safety Code-share CPP Carrier Name Partner Name Code-share Approval Safety Airline Code Partner Status** Approval Status Alaska Airlines Horizon Air QX U.S. Approved N/A Peninsula Airways (dba) Alaska Airlines KS Approved N/A PenAir U.S. Alaska Airlines Ravn Alaska 7H U.S. Approved N/A Alaska Airlines SkyWest Airlines OO U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Air Wisconsin ZW U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines British Airways BA Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Cathay Pacific Airlines CX Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines China Southern Airlines CZ Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Compass Airlines CP U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Envoy Air Inc. MQ U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines ExpressJet EV U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Fiji Airways FJ Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Finnair AY Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Iberia IB Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines JAL Airlines JL Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Jetstar Japan Co. GK Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Malaysia Airlines MH Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Mesa Airlines YV U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Piedmont Airlines PT U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines PSA Airlines OH U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Qantas QF Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines Republic Airlines YX U.S. Approved N/A American Airlines Royal Jordanian RJ Foreign N/A Approved American Airlines SkyWest Airlines OO U.S. -

Air Travel Consumer Report

Air Travel Consumer Report A Product Of The OFFICE OF AVIATION ENFORCEMENT AND PROCEEDINGS Aviation Consumer Protection Division Issued: February 2020 Flight Delays1 December 2019 Mishandled Baggage, Wheelchairs, and Scooters 1 December 2019 January - December 2019 Oversales1 4th Quarter 2019 January- December 2019 Consumer Complaints2 December 2019 (Includes Disability and January - December 2019 Discrimination Complaints) Airline Animal Incident Reports4 December 2019 January - December 2019 Customer Service Reports to 3 the Dept. of Homeland Security December 2019 1 Data collected by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Website: http://www.bts.gov 2 Data compiled by the Aviation Consumer Protection Division. Website: http://www.transportation.gov/airconsumer 3 Data provided by the Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration 4 Data collected by the Aviation Consumer Protection Division TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page Section Page Flight Delays (continued) Introduction 3 Table 8 31 Flight Delays List of Regularly Scheduled Domestic Flights Explanation 4 with Tarmac Delays Over 3 Hours, By Marketing/Operating Carrier Branded Codeshare Partners 5 Table 8A Table 1 6 List of Regularly Scheduled International Flights with 32 Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Tarmac Delays Over 4 Hours, By Marketing/Operating Carrier Operations Arriving On-Time, by Reporting Marketing Carrier Appendix 33 Table 1A 7 Mishandled Baggage Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Explanation 34 Operations Arriving On-Time, by Reporting