1863 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Boundaries

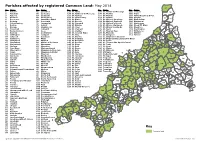

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Agenda JUNE 2021

BLISLAND PARISH COUNCIL Locum Parish Clerk: Carolyn May Tel: 07540 380531 [email protected] www.blislandparishcouncil.co.uk 2nd June 2021 TO MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL: Councillors: S Meads (Chair), K Dickin (Vice-Chair), A Green, D Holman, K Lowden, G Montague, L Spencer, M Stirling and M.Riddiford Dear Members, I hereby give you notice that the Meeting of Blisland Parish Council will be held at Blisland Village Hall on THURSDAY 10th June 2021, commencing at 7pm. Members of the public are welcome. All Members of the Council are hereby summoned to attend the Blisland Parish Council meeting, for the purpose of considering and resolving upon the business about to be transacted at the meeting as set out hereunder. Yours sincerely, Carolyn Y. May Locum Parish Clerk Press & Public are invited to attend. Meetings are held in public and could be filmed or recorded by broadcasters, the media or members of the public. Meetings of the Parish Council are not public meetings, but members of the public have a statutory right to attend meetings of the Council as observers. They have no legal right to speak unless the Parish Council Chairman authorises them to do so. If members of the public join the meeting after the public participation item on the agenda, they may not be permitted to speak. AGENDA 1. Persons Present/Apologies To NOTE persons, present and RECEIVE apologies for absence. 2. To Receive any Declarations of Interest from Members / Dispensations To RECEIVE any Declarations of Interest from Members. To RESOLVE to grant any requests for Dispensation in line with the Councillor Code of Conduct 2012 if appropriate. -

Wind Turbines East Cornwall

Eastern operational turbines Planning ref. no. Description Capacity (KW) Scale Postcode PA12/02907 St Breock Wind Farm, Wadebridge (5 X 2.5MW) 12500 Large PL27 6EX E1/2008/00638 Dell Farm, Delabole (4 X 2.25MW) 9000 Large PL33 9BZ E1/90/2595 Cold Northcott Farm, St Clether (23 x 280kw) 6600 Large PL15 8PR E1/98/1286 Bears Down (9 x 600 kw) (see also Central) 5400 Large PL27 7TA E1/2004/02831 Crimp, Morwenstow (3 x 1.3 MW) 3900 Large EX23 9PB E2/08/00329/FUL Redland Higher Down, Pensilva, Liskeard 1300 Large PL14 5RG E1/2008/01702 Land NNE of Otterham Down Farm, Marshgate, Camelford 800 Large PL32 9SW PA12/05289 Ivleaf Farm, Ivyleaf Hill, Bude 660 Large EX23 9LD PA13/08865 Land east of Dilland Farm, Whitstone 500 Industrial EX22 6TD PA12/11125 Bennacott Farm, Boyton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8NR PA12/02928 Menwenicke Barton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8PF PA12/01671 Storm, Pennygillam Industrial Estate, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7ED PA12/12067 Land east of Hurdon Road, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9DA PA13/03342 Trethorne Leisure Park, Kennards House 500 Industrial PL15 8QE PA12/09666 Land south of Papillion, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7EZ PA12/00649 Trevozah Cross, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 9LT PA13/03604 Land north of Treguddick Farm, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7JN PA13/07962 Land northwest of Bottonett Farm, Trebullett, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9QF PA12/09171 Blackaton, Lewannick, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7QS PA12/04542 Oak House, Trethawle, Horningtops, Liskeard 500 Industrial -

3 Bolingey Chapel, Chapel Hill Guide Price £177,500

3 Bolingey Chapel, Chapel Hill Bolingey, Perranporth, TR6 0DQ • No Chain Guide Price £177,500 • Ideal letting investment EPC Rating ‘51’ • Great as a second home • Good first purchase 3 Bolingey Chapel, Chapel Hill, Bolingey, Perranporth, TR6 0DQ Property Description This two double bedroom apartment is set in a chapel conversion located in the desirable hamlet of Bolingey and just one mile from the renowned golden sands of the beach at Perranporth. Having upvc double glazing and electric heating, this individual first floor apartment enjoys communal gardens and level residents parking. Enjoying rural views from the majority of windows, there is a communal access stairway, then a private hallway, two double bedrooms and modern kitchen with open access to the generous living/dining room. The bathroom also contains a separate shower cubicle in addition to a bath and the property would prove an ideal holiday or residential let as well as an excellent first purchase or second home. LOCATION Bolingey is an attractive hamlet with public house, situated approximately a 1/2 mile from Perranporth and a mile from its beach. Perranporth offers an excellent range of facilities including primary schooling and a range of shops, bars and bistros and is particularly popular for its large sandy beach renowned for its surfing conditions. Communal stairs rising to the first floor. Entrance door leading into: - ENTRANCE VESTIBULE With door to:- LOUNGE/DINING ROOM 19' 1" x 9' 4" (5.84m x 2.86m) plus recesses. Dual aspect with rural outlook from both windows. Wood effect flooring. Electric fire. Dining recess. KITCHEN 11' 8" x 6' 6" (3.57m x 2.0m) With an excellent range of base, wall and drawer units with roll edge work surface having inset 1 1/2 basin sink unit. -

St Hilary Neighbourhood Development Plan

St Hilary Neighbourhood Development Plan Survey review & feedback Amy Walker, CRCC St Hilary Parish Neighbourhood Plan – Survey Feedback St Hilary Parish Council applied for designation to undertake a Neighbourhood Plan in December 2015. The Neighbourhood Plan community questionnaire was distributed to all households in March 2017. All returned questionnaires were delivered to CRCC in July and input to Survey Monkey in August. The main findings from the questionnaire are identified below, followed by full survey responses, for further consideration by the group in order to progress the plan. Questionnaire responses: 1. a) Which area of the parish do you live in, or closest to? St Hilary Churchtown 15 St Hilary Institute 16 Relubbus 14 Halamanning 12 Colenso 7 Prussia Cove 9 Rosudgeon 11 Millpool 3 Long Lanes 3 Plen an Gwarry 9 Other: 7 - Gwallon 3 - Belvedene Lane 1 - Lukes Lane 1 Based on 2011 census details, St Hilary Parish has a population of 821, with 361 residential properties. A total of 109 responses were received, representing approximately 30% of households. 1 . b) Is this your primary place of residence i.e. your main home? 108 respondents indicated St Hilary Parish was their primary place of residence. Cornwall Council data from 2013 identify 17 second homes within the Parish, not including any holiday let properties. 2. Age Range (Please state number in your household) St Hilary & St Erth Parishes Age Respondents (Local Insight Profile – Cornwall Council 2017) Under 5 9 5.6% 122 5.3% 5 – 10 7 4.3% 126 5.4% 11 – 18 6 3.7% 241 10.4% 19 – 25 9 5.6% 102 4.4% 26 – 45 25 15.4% 433 18.8% 46 – 65 45 27.8% 730 31.8% 66 – 74 42 25.9% 341 14.8% 75 + 19 11.7% 202 8.8% Total 162 100.00% 2297 100.00% * Due to changes in reporting on data at Parish level, St Hilary Parish profile is now reported combined with St Erth. -

Cornwall. Pub 1445

TRADES DIRECTORY.] CORNWALL. PUB 1445 . Barley Sheaf, Mrs. Mary Hawken, Lower Bore st. Bodmin Commercial hotel,John Wills,Dowugate,Linkiuhorne,Liskrd Barley Sheaf, Mrs. Elizabeth Hill, Church street, Liskeard Commercial hotel & posting house, Abraham Bond, Gunnis~ Barley Sheaf inn, Fred Liddicoat, Union square, St. Columb lake, Tavistock Major R.S.O Commercial hotel & posting establishment (Herbert Henry Barley Sheaf hotel, Mrs. Elizh. E. Reed, Old Bridge st. Truro Hoare, proprietor), Grampound Road Barley Sheaf, William Richards, Gorran, St. Austell Commercial hotel, family, commercial & posting house, Basset Arms, William Laity, Basset road, Camborne William Alfred Holloway, Porthleven, Helston Basset Arms, Solomon Rogers, Pool, Carn Brea R.S. 0 Commercial hotel, family, commercial & posting, Richard Basset Arms, Charles Wills, Portreath, Redruth Lobb. South quay, Padstow R.S.O Bay Tree, Mrs. Elizabeth Rowland, Stratton R.S.O Cornish Arms, Thomas Butler, Crockwell street, Bodmin .Bennett's Arms, Charles Barriball, Lawhitton, Launceston Cornish Arms, Jarues Collins, Wadebridge R.S.O Bell inn, William Ca·rne, Meneage street, Helston Cornish Arms, Mrs. Elizh. Eddy, Market Jew st. Penzance Bell inn, Daniel Marshall, Tower street, Launceston Cornish Arms, Jakeh Glasson, Trelyon, St. Ives R.S.O Bell commercial hotel & posting house, Mrs. Elizabeth Cornish Arms, Nicholas Hawken, Pendoggett, St. Kew, Sargent, Church street, Li.skeard Wadebridge R.S.O Bideford inn, Lewis Butler, l:ltratton R.S. 0 Cornish Arms, William LObb, St. Tudy R.S.O Black Horse, Richard Andrew, Kenwyn street, Truro CornishArms,Mrs.M.A. Lucas,St. Dominick,St. MellionR. S. 0 BliBland inn, Mrs. R. Williams, Church town,Blislaud,Bodmin Cornish Arms, Rd. -

Craig an Ard, Chapel Hill, Bolingey, Perranporth, TR6 0DQ Asking Price

• Deceptive dormer bungalow Craig an Ard, Chapel Hill, Bolingey, Perranporth, TR6 0DQ Asking Price Of £425,000 • 3 bedrooms Deceptive and delightfully presented updated and extended detached family home in a lovely semi rural position within a mile of the • Bathroom and en suite shower room beach at Perranporth. 3 bedrooms, bathroom, en suite shower room and ground floor w.c. Fabulous open living space with sitting room, and generous kitchen/diner. Integral garage, oil central heating and double glazing. • Fabulous living space. Property Description Extremely deceptive detached property which has been the subject of extensive updating in recent years and offers contemporary accommodation with wonderful open living space which includes a generous sitting room with attractive stairs rising to the first floor, wide opening through to extensive kitchen/dining room with breakfast bar, granite work surfaces and sliding doors which open to the private rear garden with sunny aspect. The ground floor is completed with a wc and access exists into the integral garage. The first floor offers very well proportioned three bedroom accommodation with the master bedroom having an ensuite shower room and a good sized family bathroom containing both bath and shower cubicle. Delightful rural views are enjoyed from the first floor and rear garden. The rear garden enjoys a good degree of privacy with extensive paved patio area and steps rising to the lawned garden section. To the front of the property is a tarmacadam driveway which leads to the integral garage as well as providing additional parking space. Having oil fired central heating and double glazing, this really is a property to be viewed as it is much bigger than it first looks from the front. -

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .................................................................................................................. 19 3. Easter Sessions ............................................................................................................. 64 4. Midsummer Sessions ................................................................................................... 79 5. Summer Assizes ......................................................................................................... 102 6. Michaelmas Sessions.................................................................................................. 125 Royal Cornwall Gazette 6th January 1860 1. Epiphany Sessions These Sessions opened at 11 o’clock on Tuesday the 3rd instant, at the County Hall, Bodmin, before the following Magistrates: Chairmen: J. JOPE ROGERS, ESQ., (presiding); SIR COLMAN RASHLEIGH, Bart.; C.B. GRAVES SAWLE, Esq. Lord Vivian. Edwin Ley, Esq. Lord Valletort, M.P. T.S. Bolitho, Esq. The Hon. Captain Vivian. W. Horton Davey, Esq. T.J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. Stephen Nowell Usticke, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. F.M. Williams, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. George Williams, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. R. Gould Lakes, Esq. W.H. Pole Carew, Esq. C.A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd, Esq. H. Thomson, Esq. Augustus Coryton, Esq. Neville Norway, Esq. Harry Reginald -

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING THE QUALITY STANDARD June 1993 FWS/93/012 Author: R J Broome Freshwater Scientist NRA C.V.M. Davies National Rivers Authority Environmental Protection Manager South West R egion ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING TOE QUALITY STANDARD - FWS/93/012 This report shows the number of samples taken and the frequency with which individual determinand values failed to comply with National Water Council river classification standards, at routinely monitored river sites during the 1992 classification period. Compliance was assessed at all sites against the quality criterion for each determinand relevant to the River Water Quality Objective (RQO) of that site. The criterion are shown in Table 1. A dashed line in the schedule indicates no samples failed to comply. This report should be read in conjunction with Water Quality Technical note FWS/93/005, entitled: River Water Quality 1991, Classification by Determinand? where for each site the classification for each individual determinand is given, together with relevant statistics. The results are grouped in catchments for easy reference, commencing with the most south easterly catchments in the region and progressing sequentially around the coast to the most north easterly catchment. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 110221i i i H i m NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY - 80UTH WEST REGION 1992 RIVER WATER QUALITY CLASSIFICATION NUMBER OF SAMPLES (N) AND NUMBER -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

1859 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes

1859 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .............................................................................................................................. 24 3. Easter Sessions ........................................................................................................................ 42 4. Midsummer Sessions 1859 ...................................................................................................... 51 5. Summer Assizes ....................................................................................................................... 76 6. Michaelmas Sessions ............................................................................................................. 116 ========== Royal Cornwall Gazette, Friday January 7, 1859 1. Epiphany Sessions These sessions opened at the County Hall, Bodmin, on Tuesday the 4th inst., before the following Magistrates:— Sir Colman Rashleigh, Bart., John Jope Rogers, Esq., Chairmen. C. B. Graves Sawle, Esq., Lord Vivian. Thomas Hext, Esq. Hon. G.M. Fortescue. F.M. Williams, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. H. Thomson, Esq. T. J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. J. P. Magor, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. R. G. Bennet, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. Thomas Paynter, Esq. J. King Lethbridge, Esq. R. G. Lakes, Esq. W. H. Pole Carew, Esq. J. T. H. Peter, Esq. J. Tremayne, Esq. C. A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd, -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan)