Inculturation of Postcolonial Igbo Liturgy A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

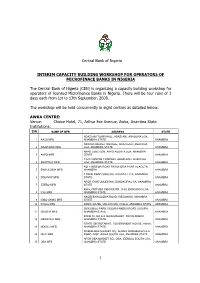

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

Spatial Distributions of Aquifer Hydraulic Properties from Pumping Test Data in Anambra State, Southeastern Nigeria

American Journal of Geophysics, Geochemistry and Geosystems Vol. 5, No. 4, 2019, pp. 119-128 http://www.aiscience.org/journal/aj3g ISSN: 2381-7143 (Print); ISSN: 2381-7151 (Online) Spatial Distributions of Aquifer Hydraulic Properties from Pumping Test Data in Anambra State, Southeastern Nigeria Christopher Chukwudi Ezeh1, Austin Chukwuemeka Okonkwo1, *, Emeka Udeze2 1Department of Geology and Mining, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria 2Anambra State Rural Water and Sanitation Agency (ANARUWASA), Awka, Nigeria Abstract Spatial distributions of aquifer hydraulic properties were carried out from direct pumping test data in Anambra State, Southeastern Nigeria. The study area lies within longitudes 06° 38I and 007° 15IE and latitudes 05°42I and 006°45IN within an area extent of about 4844sqkm (1870sqmi), underlain by four main geological formations. Pump testing was carried out in over one hundred (100) locations in the study area. The single-well test approach was used, employing the constant discharge and recovery methods. The Cooper-Jacob’s straight-line method was used to analyze the pump test results. This enabled the computing of the aquifer hydraulic properties. Correlated borehole logs show total depth range of 80meters to 250meters, with lithologic sequence of top sandy clay – medium to coarse grained sand – clay/shale – sand/sandstone, with the medium to coarse grained sand thickly underlying the central part of the study area. Static water level ranges from 100meters to 260meters at the central part and 10meters to 90meters at the adjoining areas. Aquifer transmissivity values range from 5m2/day to 80m2/day, indicating variable transmissivity potentials, while hydraulic conductivity values range from 0.5m/day to 6.0m/day. -

Growth of the Catholic Church in the Onitsha Province Op Eastern Nigeria 1905-1983 V 14

THE CONTRIBUTION OP THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OP EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 V 14 - I BY REV. FATHER VINCENT NWOSU : ! I i A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY , DEGREE (EXTERNAL), UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1988 ProQuest Number: 11015885 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015885 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 s THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OF EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 By Rev. Father Vincent NWOSU ABSTRACT Recent studies in African church historiography have increasingly shown that the generally acknowledged successful planting of Christian Churches in parts of Africa, especially the East and West, from the nineteenth century was not entirely the work of foreign missionaries alone. Africans themselves participated actively in p la n tin g , sustaining and propagating the faith. These Africans can clearly be grouped into two: first, those who were ordained ministers of the church, and secondly, the lay members. -

Community's Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His

International Journal of Literature and Arts 2019; 7(1): 1-8 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijla doi: 10.11648/j.ijla.20190701.11 ISSN: 2331-0553 (Print); ISSN: 2331-057X (Online) Community’s Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His Art Alvan-Ikoku Okwudiri Nwamara Department of Music, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria Email address: To cite this article: Alvan-Ikoku Okwudiri Nwamara. Community’s Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His Art. International Journal of Literature and Arts . Vol. 7, No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.11648/j.ijla.20190701.11 Received : September 19, 2018; Accepted : October 17, 2018; Published : March 11, 2019 Abstract: The Igbo traditional concept of “Ohaka: The Community is Supreme,” is mostly expressed in Igbo names like; Nwoha/Nwora (Community-Owned Child), Oranekwulu/Ohanekwulu (Community Intercedes/intervenes), Obiora/Obioha (Community-Owned Son), Adaora/Adaoha (Community-Owned Daughter) etc. This indicates value attached to Ora/Oha (Community) in Igbo culture. Musical studies have shown that the Igbo musical artiste does not exist in isolation; rather, he performs in/for his community and is guided by the norms and values of his culture. Most Igbo musicological scholars affirm that some of his works require the community as co-performers while some require collaboration with some gifted members of his community. His musical instruments are approved and often times constructed by members of his community as well as his costumes and other paraphernalia. But in recent times, modernity has not been so friendly to this “Ohaka” concept; hence the promotion of individuality/individualism concepts in various guises within the context of Igbo musical arts performance. -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Assessment of Human Capital Attributes Influencing Occupational Diversification Among Rural Women in Anambra State, Nigeria

International Journal of Sustainable Agricultural Research 2015 Vol.2, No.2, pp.31-44 ISSN(e): 2312-6477 ISSN(p): 2313-0393 DOI: 10.18488/journal.70/2015.2.2/70.2.31.44 © 2015 Conscientia Beam. All Rights Reserved. ASSESSMENT OF HUMAN CAPITAL ATTRIBUTES INFLUENCING OCCUPATIONAL DIVERSIFICATION AMONG RURAL WOMEN IN ANAMBRA STATE, NIGERIA † Ajani, E.N1 --- Igbokwe, E.M2 1 Department of Agricultural Extension and Communication, University of Agriculture, Makurdi, Nigeria 2 Department of Agricultural Extension, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria ABSTRACT The study was carried out in Anambra State, Nigeria to assess the influence of human capital attributes on occupational diversification among rural women. Simple random sampling technique was used in selecting 462 respondents for the study. Data was collected using questionnaire. Descriptive statistics such as percentage mean scores, standard deviation; factor analysis and correlation were used for data analysis. Results show that the respondents were mostly influenced by certain human capital attributes namely; possession of entrepreneurial skills (59.5%), number of dependants in the household (55.4%), access to information on changing demand patterns (52.6%) 52.4% and perceived health status (52.4%). They were also highly constrained by lack of women empowerment training programmes in rural areas (M= 3.5), poor skill training (M= 3.5), inadequate training opportunities (M= 3.4), poor educational attainment (M= 3.3), among others. Developing skills in rural women are keys to improving rural productivity, employability and income-earning opportunities, enhancing food security and promoting environmentally sustainable rural development and livelihoods. It was recommended that adult literacy programmes should be introduced by government and non-governmental organizations in order to help the rural women to acquire necessary education that will help them in occupational diversification. -

“Burn the Mmonwu” Contradictions and Contestations in Masquerade Perfor- Mance in Uga, Anambra State in Southeastern Nigeria

“Burn the Mmonwu” Contradictions and Contestations in Masquerade Perfor- mance in Uga, Anambra State in Southeastern Nigeria Charles Gore asked performances organized by male asso- ciations are a distinctive feature of public per- ALL PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR formance among Igbo-speaking peoples of southeastern Nigeria (Jones 1984, Cole and Ania- kor 1984) and have been the subject of attention by African art historians in the twentieth cen- tury (Ottenberg 1975, Aniakor 1978, Ugonna 1984, Henderson and MUmunna 1988, Bentor 1995). Innovation and change in terms of iconography, ritual, and dramatic presentation have always been important components to these performances, as well as flexible adaptations and responses to changing social circumstances (Figs. 1–3). However, in the last two decades, new mass movements of Christian evangelism and Pentecostalism have emerged, success- fully exhorting their members to reject masquerade as a pagan practice. During this time, in many places in southeastern Nige- ria, famous and long-standing masquerade associations have dis- banded and their masks and costumes burnt as testimonies to the efficacy of Pentecostalism, affirming the successful conversion of former masquerade members. This research examines the chal- lenges that changing localized circumstances pose to masquerade practice in one locale in southeastern Nigeria. Uga1 is located in southeastern Nigeria in Aguata Local Gov- ernment Area (LGA) in Anambra state, along the Nnewi-Okigwe expressway in Nigeria, some 40 km (25 mi.) eastwards from Onitsha on the river Niger (Fig. 4). It consisted until recently of four village units—Umueze, Awarasi, Umuoru, and Oka—spa- tially contiguous with each other and has a population of some 20,000 individuals. -

THE AESTHETICS of IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 1996 The composite scene: the aesthetics of Igbo mask theatre Ukaegbu, Victor Ikechukwu http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/2811 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. THE COMPOSITE SCENE: THE AESTHETICS OF IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR IKECHUKWU UKAEGBU A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Exeter School of Arts and Design Faculty of Arts and Education University of Plymouth May 1996. 90 0190329 2 11111 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent. Date .. 3.... M.~~J. ... ~4:l~.:. VICTOR I. UKAEGBU. ii I 1 Unlversity ~of Plymouth .LibratY I I 'I JtemNo q jq . .. I I . · 00 . '()3''2,;lfi2. j I . •• - I '" Shelfmiul(: ' I' ~"'ro~iTHESIS ~2A)2;~ l)f(lr ' ' :1 ' I . I Thesis Abstract THE COMPOSITE SCENE: THE AESTHETICS OF IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR IKECHUKWU UKAEGBU An observation of mask performances in Igboland in South-Eastern Nigeria reveals distinctions among displays from various communities. -

The Role of Folk Music in Traditional African Society: the Igbo Experience

Journal of Modern Education Review, ISSN 2155-7993, USA April 2014, Volume 4, No. 4, pp. 304–310 Doi: 10.15341/jmer(2155-7993)/04.04.2014/008 Academic Star Publishing Company, 2014 http://www.academicstar.us The Role of Folk Music in Traditional African Society: The Igbo Experience Nnamani Sunday Nnamani (Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, Federal University Ndufu-Alike Ikwo, Nigeria) Abstract: Folk music is spontaneously composed music of a race, tribe, group etc of a humble nature, orally transmitted from generation to generation with an unknown composer. The traditional Igbo society was not a literate one. We had our culture, traditions and music before the coming of the early missionaries. In the olden days, Igbo people did not derive entertainment from books rather they developed and derived joy from imaginations through oral narratives including traditional (folk) music and dance. According to Emenyonu (1978), Igbo oral tradition or folklore (oral performance) is the foundation of the traditional Igbo music and they include folksongs, folktales, proverbs, prayers including incantations, histories, legends, myths, drama, oratory and festivals. In Africa generally, music plays an important part in the lives of the people and one of the major characteristics of African music is that it has function. The various stages of the life-cycle of an individual and the life-cycles of the society are all marked with music. Key words: Igbo folk music, culture, traditions, beliefs 1. Definition Folk music is the term used to designate the traditional music of a people in contrast to the so called popular music and the serious music of concert halls and opera houses. -

Case of Omagba Erosion Site, Onitsha Anambra State, Nigeria

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Environment and Earth Science www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3216 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0948 (Online) Vol. 3, No.11, 2013 The Role of Surveying and Mapping in Erosion Management and Control: Case of Omagba Erosion Site, Onitsha Anambra State, Nigeria Ndukwe Chiemelu*, Francis Okeke, Kelechi Nwosu, Chiamaka Ibe, Raphael Ndukwu & Amos Ugwuoti. Dept. of Geoinformatics & Surveying University of Nigeria Enugu Campus * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] , [email protected] The paper was written from a project on erosion sponsored by World Bank/Federal Ministry of Environment (Nigeria Government) under NEWMAP project Abstracts Erosion has been described as the washing away of the top soil as a result of the actions of agents such as water and wind. Gully erosion, being the predominant in Southern Nigeria, is also a type of environmental degradation with a lot of disastrous consequences caused mainly by flood as a result of high precipitation, which is fallout of climate change. It can be determined, especially in terms of extent and scope, monitored and controlled. Surveyors’ contributions through provision of the necessary data, which includes, the topographic map of the area, DTM, catchment and watershed information, both centreline and cross sectional profiles of the resultant gully, the plan view of the gully and its tributaries, etc., for the research and design works on erosion control, have been examined. The data provided was also used for the computation of the volume of runoff from the catchment passing through the gully channel as well as the appropriate slope that would reduce the flow speed. -

The Identity of the Catholic Church in Igboland, Nigeria

John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin Faculty of Theology Rev. Fr. Edwin Chukwudi Ezeokeke Index Number: 139970 THE IDENTITY OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN IGBOLAND, NIGERIA Doctoral Thesis in Systematic Theology written under the supervision of Rev. Fr. Dr hab. Krzysztof Kaucha, prof. KUL Lublin 2018 1 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the growth, strength and holiness of the Catholic Church in Igboland and the entire Universal Church. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I give praise and glory to God Almighty, the creator and author of my being, essence and existence. I sincerely thank my Lord Bishop, Most Rev. Paulinus Chukwuemeka Ezeokafor for his paternal blessings, support and sponsorship. With deepest sentiments of gratitude, I thank tremendously my beloved parents, my siblings, my in-laws, friends and relatives for their great kindness and love. My unalloyed gratitude at this point goes to my brother priests here in Europe and America, Frs Anthony Ejeziem, Peter Okeke, Joseph Ibeanu and Paul Nwobi for their fraternal love and charity. My immeasurable gratitude goes to my distinguished and erudite moderator, Prof. Krzysztof Kaucha for his assiduousness, meticulosity and dedication in the moderation of this project. His passion for and profound lectures on Fundamental Theology offered me more stimulus towards developing a deeper interest in this area of ecclesiology. He guided me in formulating the theme and all through the work. I hugely appreciate his scholarly guidance, constant encouragement, thoughtful insights, valuable suggestions, critical observations and above all, his friendly approach. I also thank the Rector and all the Professors at John Paul II Catholic University, Lublin, Poland. -

STRUCTURE PLAN for Awka and SATELLITE TOWNS

AWKA STRUCTURE PLAN FOR AWKA AND SATELLITE TOWNS Anambra State STRUCTURE PLAN FOR AWKA AND SATELLITE TOWNS Anambra State 1 Structure Plan for Awka and Satellite Towns Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2009 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme publications can be obtained from UN-HABITAT Regional and Information Offices or directly from: P.O.Box 30030, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya. Fax: + (254 20) 762 4266/7 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unhabitat.org HS/1152/09E ISBN: 978-92-1-132118-0 DISCLAIMER The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), the Governing Council of UN-HABITAT or its Member States. Excerpts from this publication may be reproduced without authorisation, on condition that the source is indicated. Photo Credits : © UN-HABITAT acknowLEDGEMents Director: Dr Alioune Badiane Principal Editor: Prof. Johnson Bade Falade Co-ordinator: Dr. Don Okpala Principal Authors: Prof. Louis C. Umeh Prof. Samson O. Fadare Dr. Carol Arinze –Umobi Chris Ikenna Udeaja Tpl. (Dr) Francis Onweluzo Design and Layout: Andrew Ondoo 2 FOREWORD t is now widely It is to reverse and stem this development trend acknowledged and to realize the developmental potentials of well- and accepted that planned and managed cities, towns and villages, that citiesI and urban areas my Government approached the United Nations are engines of economic Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) in development and growth.