THEORY & PRACTICE Supervised Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Astronomical Society of Canada: Victoria Centre

ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA: VICTORIA CENTRE Comet NEOWISE, July 16th, 2020, by Daniel Posey A Comet Tale Physically isolated from their fellow RASCals, many members of the local amateur astronomy community were experiencing a state of isolation from their own telescopes, until the Comet NEOWISE called them to action. It hasn’t just been the amateur astronomy community paying attention to our celebrity comet either. With the prospects of a bright comet in the northern night sky, members of the public have been regularly gathering in large numbers, in places like Mount Tolmie, Mount Doug, and along the waterfront of Greater Victoria. SKYNEWS August 2020 ISSUE #420 Page 1 ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA: VICTORIA CENTRE The Comet NEOWISE takes its name from the Near Earth Object survey mission it was discovered on, by astronomers using the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer space telescope, long before it became the bright comet in the night sky. For those of us without space telescopes at our disposal, early on the comet was best viewed in the early hours of the morning, something prohibitive to many of us who are still working regular hours or who are allergic to getting up in the pre-dawn hours. However, by the second half of July, the comet was clearly visible in the early evening, wandering its way towards and then underneath the constellation Ursa Major. After being teased for weeks with stories of the comet of the century, we all finally had a good view of the spectacle. The arrival of the comet this year not only resulted in a renaissance of astrophotography and observing (as seen by Sherry Buttnor’s image top right and Bill Weir’s sketch bottom right), among our Centre’s membership, but has inspired many members of the public to take up astronomy as a hobby. -

Recovery Strategy for Garry Oak and Associated Ecosystems and Their Associated Species at Risk in Canada

Recovery Strategy for Garry Oak and Associated Ecosystems and their Associated Species at Risk in Canada 2001 - 2006 Prepared by the Garry Oak Ecosystems Recovery Team Draft 20 February 2002 i The Garry Oak Ecosystems Recovery Team Marilyn A. Fuchs (Chair) Foxtree Ecological Consulting, Friends of Government House Gardens Society Robb Bennett Private entomologist Louise Blight Capital Regional District Parks Cheryl Bryce Songhees First Nation Brenda Costanzo BC Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management – Conservation Data Centre Michael Dunn Environment Canada - Canadian Wildlife Service Tim Ennis Nature Conservancy of Canada Matt Fairbarns BC Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management – Conservation Data Centre Richard Feldman University of British Columbia David F. Fraser BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection – Biodiversity Branch Harold J. Gibbard Friends of Mt. Douglas Park Society, Garry Oak Meadow Preservation Society, Garry Oak Restoration Project Tom Gillespie Garry Oak Meadow Preservation Society, Victoria Natural History Society Richard Hebda Royal British Columbia Museum, University of Victoria Andrew MacDougall University of British Columbia Carrina Maslovat Native Plant Study Group of the Victoria Horticultural Society, Woodland Native Plant Nursery Michael D. Meagher Garry Oak Meadow Preservation Society, Thetis Park Nature Sanctuary Association Adriane Pollard District of Saanich, Garry oak Ecosystems Restoration Kit Committee, Garry Oak Restoration Project Brian Reader Parks Canada Agency Arthur Robinson Department of National Defence James W. Rutter JR Recreation, Management and Land Use Consulting George P. Sirk Regional District of Comox-Strathcona Board Kate Stewart The Land Conservancy of British Columbia ii Disclaimer This recovery strategy has been prepared by the Garry Oak Ecosystems Recovery Team to define recovery actions that are deemed necessary to protect and recover Garry oak and associated ecosystems and their associated species at risk. -

Western Bluebirds in Mt. Tolmie Park Spring 2014

Restoring Western Bluebirds in Mt. Tolmie Park 341 Restoration Project Brynlee Thomas, Elliot Perley, Emily Nicol, Gregory Onyewuchi , Mariya Peacosh, Maya Buckner Spring semester, 2014 1 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction……………………………………………………………………...…………………4 1.1 Biological background……………………………………………………................................4 1.1.1 Life History……………………………………………………………………….6 1.1.2 Habitat Requirements…………………………………………..…………………7 1.1.3 Threats………………………………………………………………………...….8 1.2 Site analysis………………………………………………………………………………..…10 1.2.1 Site Description……………………………………………..…………………..10 1.2.2 Climate and Geology…………………………………………...........................11 1.2.3 Cultural History……………………………………………………………...…12 1.2.4 Native Vegetation..……………………………………………………………..14 1.2.5 Animal Species……………………………………………………………..… 15 1.2.6 Invasive Species………………………………………………..………………16 2.0 Goals and Objectives……………………………………………………………………………...19 3.0 Implementation Plan………………………………………………………………………………22 3.1 Nest boxes…………………………………………………………………………………….22 3.1.1 Aviaries and release………………………………………….…………………23 3.1.2 Predator avoidance…………………………………….………………………..24 3.1.3 Food attractants……………………….………………………………………...25 3.1.4 Nest boxes locations……………………………………………………………25 3.1.3 Determine amount of nest boxes……………………………………………….26 3.2 Community Awareness and Involvement………………………………………….…………28 3.3 Timeline……………………………………………………...………………………….……29 3.4 Policies………………………………………...……………....……………………………..31 3.5 Budgets and Funding Proposal………………………………………...………………………….……….………...31 3.5.1 Constraints…………………………………………………………………...…34 -

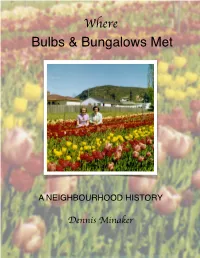

Bulbs & Bungalows

Where Bulbs & Bungalows Met A NEIGHBOURHOOD HISTORY Dennis Minaker For Val, with thanks i Where Bulbs & Bungalows Met -A Neighbourhood History- Summer 2015 Research and text by Dennis Minaker Layout by Val Minaker Here-At-Home Publishing 1669 Freeman Avenue, Victoria BC V8P1P5 Cover photograph: Marion Dempster and Barbara Underwood kneeling in Dempster tulip fields, Spring of 1957. Looking south from these Freeman Avenue houses (numbers 1669 to 1673) meant a view of the distant Olympic Mountains - before construction began along Kingsley Place. Opposite: Aerial view of Shelbourne Valley, 1928. Shelbourne Street runs up the middle, between Cedar Hill Road (left) and Richmond Road (right), to meet Cedar Hill Cross Road at the top. University School (now St. Michaels University School) with its curving driveway is at lower right, immediately below Knight Avenue. Only fenced field and orchards lie between that rough road and Pear Street to the north. Bowker Creek, open to the summer sun, snakes through fields at lower left. ii iii Contents Acknowledgements & Introduction 1 Mount Tolmie Nursery 2 Dempster Brothers’ Greenhouse 9 The Whiteoaks of Cedar 14 And Then Came Suburbia 19 St. Michaels University School 27 Additional Notes of the Greater Area 32 First Homeowners, 1950-1957 35 Index 38 "1 Acknowledgments & Introduction Bugles, bulbs and bungalows - all bound together in time - make for a curious local history. But each came to light during my research of this past winter. Longtime neighbours Bob Foster and Bob Rogerson set me in motion when they recalled buying their houses (around 1949) from the original contractors, Paine and Townsend. -

News Clipping Files

News Clipping Files News Clipping File Title File Number Abkhazi Gardens (Victoria, B.C.) 3029 Abkhazi, Margaret, Princess 8029 Academy Close (Victoria, B.C.) 3090 Access to information 9892 Accidents 3287 Actors 3281 Adam, James, 1832-1939 3447 Adams, Daniel (family) 7859 Adaskin, Murray 6825 Adey, Muriel, Rev. 6826 Admirals Road (Esquimalt, B.C.) 2268 Advertising 45 Affordable housing 8836 Agnew, Kathleen 3453 Agricultural organizations 1989 Agriculture 1474 Air mail service 90 Air travel 2457 Airports 1573 Airshows 1856 Albert Avenue (Victoria, B.C.) 2269 Alder Street (Victoria, B.C.) 9689 Alexander, Charles, 1824-1913 (family) 6828 Alexander, Fred 6827 Alexander, Verna Irene, 1906-2007 9122 Alexander-Haslam, Patty (family) 6997 Alexis, Johnny 7832 Allen, William, 1925-2000 7802 Alleys 1947 Alting, Margaretha 6829 Amalgamation (Municipal government) 150 Amelia Street (Victoria, B.C.) 2270 Anderson, Alexander Caulfield 6830 Anderson, Elijah Howe, 1841-1928 6831 Andrews, Gerald Smedley 6832 Angela College (Victoria, B.C.) 2130 Anglican Communion 2084 Angus, James 7825 Angus, Ronald M. 7656 Animal rights organizations 9710 Animals 2664 Anscomb, Herbert, 1892-1972 (family) 3484 Anti-German riots, Victoria, B.C., 1915 1848 Antique stores 441 Apartment buildings 1592 City of Victoria Archives News Clipping Files Appliance stores 2239 Arbutus Road (Victoria, B.C.) 2271 Archaeology 1497 Archery 2189 Architects 1499 Architecture 1509 Architecture--Details 3044 Archivists 8961 Ardesier Road (Victoria, B.C.) 2272 Argyle, Thomas (family) 7796 Arion Male Voice Choir 1019 Armouries 3124 Arnold, Marjoriem, 1930-2010 9726 Arsens, Paul and Artie 6833 Art 1515 Art deco (Architecture) 3099 Art galleries 1516 Art Gallery of Greater Victoria 1517 Art--Exhibitions 1876 Arthur Currie Lane (Victoria, B.C.) 2853 Artists 1520 Arts and Crafts (Architecture) 3100 Arts organizations 1966 Ash, John, Dr. -

A Profile of the Wellbeing of Victoria Capital Region Residents

Victoria Capital Region Community Wellbeing Survey: A Profile of the Wellbeing of Victoria Capital Region Residents A preliminary report for The Victoria Foundation and Capital Region District Keely Phillips Margo Hilbrecht Bryan Smale Canadian Index of Wellbeing University of Waterloo August 2014 Phillips, K., Hilbrecht, M., & Smale, B. (2014). A Profile of the Wellbeing of Capital Region Residents. A Preliminary Report for the Victoria Foundation and Capital Region District. Waterloo, ON: Canadian Index of Wellbeing and the University of Waterloo. © 2014 Canadian Index of Wellbeing Contents What is Wellbeing? 1 Introduction 3 Demographic Profile 8 Community Vitality 16 Healthy Populations 22 Demographic Engagement 26 Environment 28 Leisure and Culture 30 Education 37 Living Standards 39 Time Use 44 Overall Wellbeing 49 Comments 52 i What is Wellbeing? There are many definitions of wellbeing. The Canadian Index of Wellbeing has adopted the following as its working definition: The presence of the highest possible quality of life in its full breadth of expression focused on but not necessarily exclusive to: good living standards, robust health, a sustainable environment, vital communities, an educated populace, balanced time use, high levels of democratic participation, and access to and participation in leisure and culture. 1 2 Introduction The Victoria Capital Region Community Wellbeing Survey was launched on May 5, 2014 when invitations to participate were mailed to 15,841 randomly selected Capital District Region households. This represented approximately 10% of all households in the region, divided proportionally across all municipal areas. One person in each household, aged 18 years or older, was invited to complete the questionnaire. -

Saanich Inlet, Southern Vancouver Island Geology of an Aspiring Global Geopark Saanich Inlet: an Aspiring Global Geopark

Saanich Inlet, southern Vancouver Island Geology of an Aspiring Global Geopark Saanich Inlet: An Aspiring Global Geopark In anticipation of a proposal to the UNESCO Global Geopark Network, the Canadian National Committee for Global Geoparks has accepted Saanich Inlet and its watershed on southern Vancouver Island as an Aspiring Geopark. This Geopark initiative, led by the Saanich Inlet Protection Society, is seeking the support of local residents, First Nation communities, businesses, marine groups and scientists from government, universities, and industry. Geoparks are community-driven enterprises that reflect the desires and values of the people living in them. This Geopark will protect the natural resources and cultural heritage of Saanich Inlet while encouraging environmentally sound economic development. Geoheritage recognizes the continuum between the geological record and cultural values. Like the more than 75 Geoparks worldwide, Saanich Inlet has an internationally significant geologic record that has been intensively researched on land and in the sea. It also has a long human history, enduring cultural traditions, vibrant communities, and environmentally respectful commercial activities. The Saanich Inlet region offers exceptional opportunities for public education. It includes the City of Victoria, a major global tourist destination. Although small, the region is rich in venues for experiential learning about oceanography, tectonics, paleogeographic reconstructions, the most recent ice age, and modern coastal and deep-water processes. Easy access to the inlet’s geology is provided by extensive hiking trails, bike paths, road cuts, public beaches, and docking facilities, many of which are in provincial and municipal parks. Visitors will gain an increased appreciation of our natural heritage and a better grasp of the interactive feedbacks between land, air, water, organisms, and human activity. -

Downtown Victoria Downtown Victoria

s d n a l s Port I f Hardy l u E SS ST BRITISH G PRI NC & COLUMBIA r e v Port 19 u o Alice c n a V VA NCOUVER 99 PEMBROKE ST Lands o E t Campbell n ISLAND 1 d Save-On-Foods River Powell R Gold River Whistler d Swartz Bay Memorial Centre River 19 Deep Cove 0 0 Courtenay Wain Rd Saanich Y ST 9 19A 1 Qualicum Squamish BA W. LEGEND Y ST DOUGLAS ST Beach i 4 Ferry (International) DISCOVER Tofino Port Parksville n n Vancouver n e Nanaimo 17 e v Alberni Mill Bay v a Harbour Ferry Stop Ucluelet a Ladysmith Gulf 15 h th Islands 1 Mills Rd t s Seaplane Bamfield Chemainus Patricia Bay s CALEDONIA ST e Juan Islands & An Re Duncan R San aco Port San Juan to rtes Washrooms 1 Saanich 23 24 Islands THAM ST N Renfrew 14 Saanich Inlet BBeaconeacon i Visitor Centre CHA Pacific Anacortes Inlet Victoria Int’l. SIDNEY Gulf Islands GOVERNMENT ST Airport Downtown Attractions Ocean Sooke VICTORIA National Park 0 5 Reserve — Sidney Spit 8 0 BLANSHARD ST Port Angeles Walkway 1 T McTavish Rd Saancih Rd Saancih r an E . WASHINGTON W. s S a HERALD ST Seattle C L 0 STATE a Sidney Island a ochs 0 n n WILSON RD 7 i ad c 1 h i a de Dr John Dean To H Prov. Park FISGARD ST PLACES OF INTEREST / w 17A DISTANCE CHART AND Duncan & y HARBOUR RD ATTRACTIONS Nanaimo to DRIVING TIMES Mt. -

Where Bulbs and Bungalows

Where Bulbs & Bungalows Met A NEIGHBOURHOOD HISTORY Dennis Minaker For Val, with thanks i Where Bulbs & Bungalows Met -A Neighbourhood History- Summer 2015 Research and text by Dennis Minaker Layout by Val Minaker Here-At-Home Publishing 1669 Freeman Avenue, Victoria BC V8P1P5 Cover photograph: Marion Dempster and Barbara Underwood kneeling in Dempster tulip fields, Spring of 1957. Looking south from these Freeman Avenue houses (numbers 1669 to 1673) meant a view of the distant Olympic Mountains - before construction began along Kingsley Place. Opposite: Aerial view of Shelbourne Valley, 1928. Shelbourne Street runs up the middle, between Cedar Hill Road (left) and Richmond Road (right), to meet Cedar Hill Cross Road at the top. University School (now St. Michaels University School) with its curving driveway is at lower right, immediately below Knight Avenue. Only fenced field and orchards lie between that rough road and Pear Street to the north. Bowker Creek, open to the summer sun, snakes through fields at lower left. ii iii Contents Acknowledgements & Introduction 1 Mount Tolmie Nursery 2 Dempster Brothers’ Greenhouse 9 The Whiteoaks of Cedar 14 And Then Came Suburbia 19 St. Michaels University School 27 Additional Notes of the Greater Area 32 First Homeowners, 1950-1957 35 Index 38 "1 Acknowledgments & Introduction Bugles, bulbs and bungalows - all bound together in time - make for a curious local history. But each came to light during my research of this past winter. Longtime neighbours Bob Foster and Bob Rogerson set me in motion when they recalled buying their houses (around 1949) from the original contractors, Paine and Townsend. -

Ra Is 91 Now

Barbara is 91 now. She still dreams of dancing. For seniors in care, therapy programs feed body and soul. During balance and mobility therapy, Barbara’s dream comes to life as she moves to the music on her imaginary dance floor. Keep dreams alive with a donation to Eldercare Foundation, or consider A Community creating a lasting legacy for seniors in need with Resource Handbook a gift in your Will. For The Capital Region 14th Edition 1454 Hillside Ave., Victoria, BC V8T 2B7 250-370-5664 www.gvef.org Charity# 898816095 RR0001 Produced by Seniors Serving Seniors 250-413-3211 Eldercare Foundation Senior Services Directory Back Cover B&W ad - 6.875”w x 9.25”h prepared by Art Department Design 250 381-4290 Created: June 2020 Information Services ................................................................................................4 Information on community services, government services and multi-cultural services. Activity and Recreation Centres ................................................................................6 Adult Day Programs & Bathing Programs .................................................................9 Programs that meet the social needs of seniors who require assistance due to health- related matters. Centres that assist seniors who cannot use bathing facilities at home. Counselling ............................................................................................................ 10 Support for abuse, addictions, bereavement, crisis, families, and mental health. Financial Assistance ..............................................................................................14 -

Mount Tolmie–Camosun Community Plan DRAFT As of OCTOBER 1

Mount Tolmie–Camosun Community Plan DRAFT as of OCTOBER 1, 2017 Finalization subject to further work with the Mount Tolmie Community Association and Camosun Community Association [TITLE PAGE] We acknowledge that the lands discussed in this document are the traditional territories of Coast Salish peoples, specifically the Lekwungen and WSÁNEĆ peoples. This Plan has been prepared by Caleb Horn, B.A. Geog. (Hons.) UVic 2014, M.U.P. McGill 2017 Endorsed by: Mount Tolmie Community Association [date 2017] _____________________________________ Camosun Community Association [date 2017] _____________________________________ Any future amendments to this Plan must be accepted by both the Mount Tolmie Community Association and Camosun Community Association or their successor organization(s). i Acknowledgements [To be completed for Final Draft] ii Executive Summary [To be completed for Final Draft] iii Table of Contents Plan Layout Sections 1-2 provide the context of the Plan Sections 3-7 comprise the Plan’s vision and policies Section 8 offers a conclusion to the Plan Table of Contents ................................................................................................................ iv List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... vi List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... vii 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................. -

Provincial Museum

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT OF THE PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF N ArrURAL HISTORY F OR TH E YEAR 1936 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VlCl'OHIA, B.C.: Printed by CHARLES F. BANFIELD, Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1937. To His Honour E. W. HAMBER, Lieutenant-Governo1· of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History for the year 1936. G. M. WEIR, Provincial S ec retary. P1·ovincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, B.C. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, VICTORIA, B.C., January 27th, 1937. The Honourable Dr. G. M. Weir, Provincial Secreta1·y, Victo1·ia, B.C. Sm,-I have the honour, as Director of the Provincial Museum of Natural History, to lay before you the Report for the year ended December 31st, 1936, covering the activities of the Museum. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, F. KERMODE, Director. - ~ DEPARTMENT of the PROVINCIAL SECRETARY. The Honourable Dr. G. M. WEIR, Minister. P. WALKER, Deputy Ministe1·. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY. Staff: FRANCIS KERMODE, Directo1·. I. McTAGGART COWAN, Ph.D., Assistant Biologist. MARGARET CRUMMY, Recorder. WINIFRED V. HARDY, Stenog1·apher. LILLIAN C. SWEENEY, Assistant Preparator. J. ANDREW, Attendant. I V) .. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE. Objects...... --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Visitors-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------