Russian and Soviet Cinema Russian and Soviet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sergei Eisenstein on the Visual Arts

IMT School for Advanced Studies, Lucca Lucca, Italy Art History as Janus: Sergei Eisenstein on the Visual Arts PhD Program in Analysis and Management of Cultural Heritage XXXth cycle By Hanin Hannouch 2017 The dissertation of Hanin Hannouch is approved Program Coordinator: Emanuele Pellegrini, IMT School for Advanced Studies Advisor: Linda Bertelli, IMT School for Advanced Studies Co-Advisor: Alessia Cervini, Universita© degli Studi di Messina The dissertation of Hanin Hannouch has been reviewed by: Prof. Pietro Montani, Sapienza Universita di Roma Dr. Marie Rebecchi, University of Paris III Sorbonne Nouvelle 3 IMT School for Advanced Studies, Lucca 2017 ART HISTORY AS JANUS: SERGEI EISENSTEIN ON THE VISUAL ARTS CONTENTS LIST OF IMAGES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VITA AND PUBLICATIONS ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Ausblick: Cinematic Paintings- Case Studies I ± VALENTIN SEROV 1 Yermolova 1.1 Mirror in the set-up 1.2 Dynamic light 2 Seeing intraconceptual movement 3 Art history answers back 3.1 Vanishing points and diagonals II- EL GRECO 4 The Expulsion of the Moneylenders from the Temple 4.1 Unecstatic 4.2 Mechanical repetition 5 The Resurrection from the Grave 5.1 Format 5.2 Theme 5.3 Pathos and ecstasy 6 An art historical transformation 7 Storm over Toledo 7.1 Level of subjectivity 7.2 28 mm painting 8 Art historical comparison between Storm over Toledo and View and Plan of Toledo III- GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIRANESI 9 Carcere with Staircase 9.1 Independent value 9.2 Biographical change 9.3 Accumulation of perspective 10 Art History Looks at The Dark Prison -

Volodymyr Vynnychenko and the Early Ukrainian Decadent Film (1917–1918)

УДК 008:791.43.01 O. Kirillova volodymyr vynnychenKo and the early uKrainian decadent film (1917–1918) The article is focused on the phenomenon of the early Ukrainian decadent cinema, in particular, in rela- tion to filmings of Volodymyr Vynnychenko’s dramaturgy. One of the brightest examples of ‘film decadence’ in Vynnychenko’s oevre is “The Lie” directed by Vyacheslav Vyskovs’ky in 1918, discovered recently in the film archives. This film displays the principles of ‘ethical symbolism’, ‘dark’ expressionist aesthetics and remains the unique masterpiece of specifically Ukranian film decadence. Keywords: decadent film, fin de sciècle, cultural diffusion, cultural split, ethical symbolism, filming, editing. The early Ukranian decadent film as an integral screening, «The Devil’s Staircase», filmed by a Rus part of the trend of decadence in the world cinema sian producer Georgiy Azagarov in 1917 (released can be regarded as a specific problem for research in February 1918) put the central conflict in the area ers because of its diffusion within the cinematogra of circus actors. This film had been considered des phy of Russian Empire. Ukrainian subjects in the perately lost. The second “Black Panther” was taken cinema of 1910s, on the one hand, had traditionally into production by Sygyzmund Kryzhaniv’sky on been related to «ethnographical topics» (to begin “Ukrainfil’m” – in 1918. Unfortunately, the produc with the one of the earliest Russian silents «Taras tion had not been finished due to the regular change Bul’ba», 1909, after Mykola Hohol’), but, on the of government in Ukraine. Finally, the third one, other hand, had been represented partly in Russian “Die Schwarze Pantherin” filmed in Germany by film, though totally diffused in its cultural contexts. -

Cuban and Russian Film (1960-2000) Hillman, Anna

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Carnivals of Transition: Cuban and Russian Film (1960-2000) Hillman, Anna The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/9733 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] 1 Carnivals of Transition: Cuban and Russian Film (1960-2000) Anna M. Hillman Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Ph.D. degree. Queen Mary, University of London, School of Languages, Linguistics and Film. The candidate confirms that the thesis does not exceed the word limit prescribed by the University of London, and that work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given to research done by others. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on ‘carnivals of transition’, as it examines cinematic representations in relation to socio-political and cultural reforms, including globalization, from 1960 to 2000, in Cuban and Russian films. The comparative approach adopted in this study analyses films with similar aesthetics, paying particular attention to the historical periods and the directors chosen, namely Leonid Gaidai, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, El’dar Riazanov, Juan Carlos Tabío, Iurii Mamin, Daniel Díaz Torres and Fernando Pérez. -

Art and Technology Between the Usa and the Ussr, 1926 to 1933

THE AMERIKA MACHINE: ART AND TECHNOLOGY BETWEEN THE USA AND THE USSR, 1926 TO 1933. BARNABY EMMETT HARAN PHD THESIS 2008 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ANDREW HEMINGWAY UMI Number: U591491 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591491 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Bamaby Emmett Haran, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis concerns the meeting of art and technology in the cultural arena of the American avant-garde during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It assesses the impact of Russian technological Modernism, especially Constructivism, in the United States, chiefly in New York where it was disseminated, mimicked, and redefined. It is based on the paradox that Americans travelling to Europe and Russia on cultural pilgrimages to escape America were greeted with ‘Amerikanismus’ and ‘Amerikanizm’, where America represented the vanguard of technological modernity. -

Print ED368613.TIF

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 613 SO 023 661 TITLE Resource Guide to Teaching Aids in Russian and East European Studies. Revised. INSTITUTION Indiana Univ., Bloomington. Russian and East European Inst. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE Aug 93 NOTE 66p. AVAILABLE FROMRussian and East European Institute, Indiana Univ., Ballantine Hall 565, Bloomington, IN 47405. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; Educational Media; Elementary Secondary Education; *European History; Foreign Countries; Global Approach; Higher Education; History Instruction; International Education; Multicultural Education; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Eastern European Studies; Europe (East); Global Education; Poland; Russia; *Russian Studies; USSR (Russia) ABSTRACT This document contains an annotated listing of instructional aids for Russian and East European studies that are available for loan or rent from Indiana University (Bloomington). The materials are divided into nine sections:(1) slide programs; (2) filmstrips available from the Indiana University (IU) Russian and East European Institute;(3) audio cassettes;(4) books, teaching aids, and video kits;(5) films and videotapes available through the IU Russian and East European Institute;(6) a Russian and East European Institute (REEI) order form for obtaining materials from the REEI; (7)film-, and videotapes from the IU Audio-Visual Center;(8) an IU order form for obtaining films from the IU Audio-Visual Center; and (9) films, videotapes, and slides that are available from the IU Polish Studies Center. The first section on slide programs includes 5 on Eastern Europe and 9 on Russia and the Soviet successor states. The second grouping, filmstrips from IU REEI, lists 9 sound filmstrips and an additional section of Russian captioned filmstrips produced in the Soviet Union. -

Soviet Science Fiction Movies in the Mirror of Film Criticism and Viewers’ Opinions

Alexander Fedorov Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions Moscow, 2021 Fedorov A.V. Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions. Moscow: Information for all, 2021. 162 p. The monograph provides a wide panorama of the opinions of film critics and viewers about Soviet movies of the fantastic genre of different years. For university students, graduate students, teachers, teachers, a wide audience interested in science fiction. Reviewer: Professor M.P. Tselysh. © Alexander Fedorov, 2021. 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. Soviet science fiction in the mirror of the opinions of film critics and viewers ………………………… 4 2. "The Mystery of Two Oceans": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………….. 117 3. "Amphibian Man": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………………………….. 122 3. "Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin": a novel and its adaptation …………………………………………….. 126 4. Soviet science fiction at the turn of the 1950s — 1960s and its American screen transformations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 130 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 136 Filmography (Soviet fiction Sc-Fi films: 1919—1991) ……………………………………………………………. 138 About the author …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 150 References……………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………….. 155 2 Introduction This monograph attempts to provide a broad panorama of Soviet science fiction films (including television ones) in the mirror of -

Portraying Religion and Peace in Russian Film

Edinburgh Research Explorer Portraying Religion and Peace in Russian Film Citation for published version: Mitchell, J 2008, 'Portraying Religion and Peace in Russian Film', Studies in World Christianity, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 142-152. https://doi.org/10.3366/E1354990108000129 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/E1354990108000129 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Studies in World Christianity Publisher Rights Statement: ©Mitchell, J. (2008). Portraying Religion and Peace in Russian Film. Studies in World Christianity, 14(2), 142- 152doi: 10.3366/E1354990108000129 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 JOLYON MITCHELL Portraying Religion and Peace in Russian Film Peace and religion have taken on many cinematic guises in Russia over the last century. In the earliest days of Russian cinema, on the rare occasions when the Orthodox Church was represented on film, it was often depicted as a background force of social cohesion and a preserver of the peace. -

Television in the Cinema Before 1939: an International Annotated Database, with an Introduction by Richard Koszarski

Journal of e-Media Studies Volume 5, Issue 1, 2016 Dartmouth College Television in the Cinema Before 1939: An International Annotated Database, with an Introduction by Richard Koszarski Richard Koszarski and Doron Galili Visions of the Future An Introduction by Richard Koszarski Albert Abramson traced the first appearance of the word television to a paper presented in Paris by the Russian electrical engineer Constantin Perskyi on August 25, 1900. Perskyi discussed his own work as well as the contributions of his predecessors, such as Paul Nipkow, and suggested television as a replacement for words like telectroscope, one of many terms already in common use whenever the phenomenon of distant electric vision was under discussion. The International Electricity Congress, which heard the paper, was meeting in Paris that summer because this is where the great Exposition Universelle of 1900 was being held. For film historians, the exposition is renowned for its fabulous array of new projection technologies, involving everything from widescreen and color to talking pictures and Cineorama. Perskyi's linguistic contribution, on the other hand, is remembered only by specialists. One wonders if the proponents of the téléoscope and the téléphote, as they roamed the exposition, gave any thought to these new marvels of the cinema, and asked themselves why their medium still lagged so far behind in every conceivable measure. Seeing at a distance was a notion that had captivated engineers and entrepreneurs since word of Alexander Graham Bell's telephone first began to spread in the late 1870s, yet here it was 1900, and still only in the talking stage? People around the world had been waiting for television for decades, but the engineers had given them the cinema instead, a rival moving-image medium that appeared to have leapt from dream to multinational industry almost overnight. -

Leonid Gaidai ̘͙” ˪…˶€ (Ìž'í'ˆìœ¼ë¡Œ)

Leonid Gaidai ì˜í ™” 명부 (작품으로) Borrowing https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/borrowing-matchsticks-171305/actors Matchsticks Kidnapping, https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kidnapping%2C-caucasian-style-1953944/actors Caucasian Style Bootleggers https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bootleggers-1963916/actors Sportloto-82 https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sportloto-82-1964207/actors Dangerous for https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dangerous-for-your-life%21-1965544/actors Your Life! Weather Is Good on Deribasovskaya, https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/weather-is-good-on-deribasovskaya%2C-it-rains-again-on-brighton- It Rains Again beach-2370102/actors on Brighton Beach Dog Barbos and https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dog-barbos-and-unusual-cross-2370785/actors Unusual Cross The Twelve https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-twelve-chairs-2371262/actors Chairs Operation Y and Other Shurik's https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/operation-y-and-other-shurik%27s-adventures-2513681/actors Adventures Private Detective, or https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/private-detective%2C-or-operation-cooperation-3944627/actors Operation Cooperation Strictly Business https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/strictly-business-4157228/actors A Weary Road https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-weary-road-4164503/actors A Groom from https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-groom-from-the-other-world-4179373/actors the Other World Thrice https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/thrice-resurrected-4255603/actors Resurrected It Can't Be! https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/it-can%27t-be%21-4315419/actors Absolutely https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/absolutely-seriously-4426171/actors Seriously Ivan Vasilievich: Back to the https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ivan-vasilievich%3A-back-to-the-future-777739/actors Future Incognito from https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/incognito-from-st.-petersburg-930153/actors St. -

Queen of Spades in Silent Russian Cinema // Liberal Arts in Russia

ISSN 2305-8420 Российский гуманитарный журнал. 2019. Том 8. №2 91 DOI: 10.15643/libartrus-2019.2.1 (In)visible text: Queen of Spades in si lent Russian cinema © K. Hainová Palacký University in Olomouc 10 Křížkovského, Olomouc 779 00, Czech Republic. Email: [email protected] Alexander Pushkin ’s literary works have been an inspiration for the cinema already from the emergence of the narrative fiction film. One of Pushkin ’s most frequently adapted stories is a mystical novella Queen of Spades written in 1833. In Russian silent cinema, there were different versions of the story – the first one appeared as a short film in early 1910 and was directed by Pyotr Chardynin, another already a feature -length version was made in 1916 by Yakov Protazanov. While Protazanov’s version follows Pushkin’s story more closely, Chardynin also seems to draw heavily o n Tchaikovsky’s eponymous opera, which makes his film more reliant on the viewer ’s prior knowledge of the original text. The article focuses on both films, particularly on their means of transferring Pushkin’s original text o n screen. By comparing them to each other as well as with their original source materials (hypotext in Genette’s terminology), it also de- fines the degree of intertextuality in relation to the viewer ’s understanding of the re- sulting hypertext. Keywords: Alexander Pushkin, Queen of Spades, silent cinema, intertextuality, te xt transfer, theory of adaptation. There is a curious story connected with Pushkin’s novel Queen of Spades and the famous Russian actor and television film director Mikhail Kozakov. -

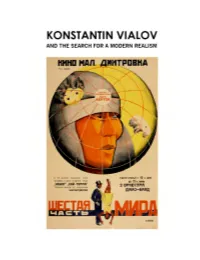

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

Mediaobrazovanie) Media Education (M Ediaobrazovanie

Media Education (Mediaobrazovanie) Has been issued since 2005. ISSN 1994–4160. E–ISSN 1994–4195 2020, 60(1). Issued 4 times a year EDITORIAL BOARD Alexander Fedorov (Editor in Chief ), Prof., Ed.D., Rostov State University of Economics (Russia) Imre Szíjártó (Deputy Editor– in– Chief), PhD., Prof., Eszterházy Károly Fõiskola, Department of Film and Media Studies. Eger (Hungary) Ben Bachmair, Ph.D., Prof. i.r. Kassel University (Germany), Honorary Prof. of University of London (UK) Oleg Baranov, Ph.D., Prof., former Prof. of Tver State University Elena Bondarenko, Ph.D., docent of Russian Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), Moscow (Russia) David Buckingham, Ph.D., Prof., Loughborough University (United Kingdom) Emma Camarero, Ph.D., Department of Communication Studies, Universidad Loyola Andalucía (Spain) Irina Chelysheva, Ph.D., Assoc. Prof., Anton Chekhov Taganrog Institute (Russia) Alexei Demidov, head of ICO “Information for All”, Moscow (Russia) Svetlana Gudilina, Ph.D., Russian Academy of Education, Moscow (Russia) Tessa Jolls, President and CEO, Center for Media Literacy (USA) Nikolai Khilko, Ph.D., Omsk State University (Russia) Natalia Kirillova, Ph.D., Prof., Ural State University, Yekaterinburg (Russia) Sergei Korkonosenko, Ph.D., Prof., faculty of journalism, St– Petersburg State University (Russia) Alexander Korochensky, Ph.D., Prof., faculty of journalism, Belgorod State University (Russia) W. James Potter, Ph.D., Prof., University of California at Santa Barbara (USA) Robyn Quin, Ph.D., Prof., Curtin University, Bentley, WA (Australia) Alexander Sharikov, Ph.D., Prof. The Higher School of Economics, Moscow (Russia) Vladimir Sobkin, Acad., Ph.D., Prof., Head of Sociology Research Center, Moscow (Russia) Kathleen Tyner, Assoc. Prof., Department of Radio– Television– Film, The University of Texas at Austin (USA) Svetlana Urazova, PhD., Assoc.