Railway Passenger Franchises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cytundeb Diffiniadau

TO BE EXECUTED AS A DEED DEFINITIONS AGREEMENT SECRETARY OF STATE FOR TRANSPORT (1) and WELSH MINISTERS (2) 1 45763.11 THIS DEFINITIONS AGREEMENT is dated 2018 BETWEEN (1) THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR TRANSPORT whose principal address is Great Minster House, 33 Horseferry Road, London SW1P 4DR (the “Secretary of State”); and (2) WELSH MINISTERS whose principal place of business is Crown Building, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3NQ ("Welsh Ministers)" (including, as appropriate, Affiliates or subsidiaries of Welsh Ministers acting on its behalf), each a “Party” and together the “Parties”. WHEREAS: (A) The Secretary of State and Welsh Ministers propose to enter into a number of agreements (the “Wales & Borders Agreements”) in connection with Welsh Ministers acting as agent for the Secretary of State in respect of certain English services which are specified in a Welsh franchise agreement. (B) The Secretary of State and Welsh Ministers wish to set out in this Agreement, definitions of the terms used in the Wales & Borders Agreements. NOW IT IS AGREED as follows: 1. CONSTRUCTION AND INTERPRETATION In the Wales & Borders Agreements, except to the extent the context otherwise requires: (a) words and expressions defined in the Railways Act have the same meanings when used therein provided that, except to the extent expressly stated, “railway” shall not have the wider meaning attributed to it by Section 81(2) of the Act; (b) words and expressions defined in the Interpretation Act 1978 have the same meanings when used in the Wales & Borders Agreements; -

Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia

Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Contents Foreword 3 Looking Ahead 5 Priorities in Detail • Great Eastern Main Line 6 • West Anglia Main Line 6 • Great Northern Route 7 • Essex Thameside 8 • Branch Lines 8 • Freight 9 A five county alliance • Norfolk 10 • Suffolk 11 • Essex 11 • Cambridgeshire 12 • Hertfordshire 13 • Connecting East Anglia 14 Our counties connected 15 Foreword Our vision is to release the industry, entrepreneurship and talent investment in rail connectivity and the introduction of the Essex of our region through a modern, customer-focused and efficient Thameside service has transformed ‘the misery line’ into the most railway system. reliable in the country, where passenger numbers have increased by 26% between 2005 and 2011. With focussed infrastructure We have the skills and enterprise to be an Eastern Economic and rolling stock investment to develop a high-quality service, Powerhouse. Our growing economy is built on the successes of East Anglia can deliver so much more. innovative and dynamic businesses, education institutions that are world-leading and internationally connected airports and We want to create a rail network that sets the standard for container ports. what others can achieve elsewhere. We want to attract new businesses, draw in millions of visitors and make the case for The railways are integral to our region’s economy - carrying more investment. To do this we need a modern, customer- almost 160 million passengers during 2012-2013, an increase focused and efficient railway system. This prospectus sets out of 4% on the previous year. -

Railfuture Response to Consultations on the Proposed East Coast Main Line Timetable May 2022

RAILFUTURE RESPONSE TO CONSULTATIONS ON THE PROPOSED EAST COAST MAIN LINE TIMETABLE MAY 2022 From: Railfuture Passenger Group & Branches: East Anglia, East Midlands, Lincolnshire, London & South East, North East, North West, Yorkshire & Scotland Submitted to: CrossCountry, Great Northern/Thameslink, LNER, Northern, TransPennine Express Copied to: East Midlands Railway, First East Coast Trains, Grand Central, Hull Trains, Network Rail & ScotRail Index Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary....................................................................................................................................... 2 Strategic Interventions .................................................................................................................................. 3 LNER ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Responses to LNER Questionnaire ............................................................................................ 6 TransPennine Express .................................................................................................................................. 9 CrossCountry ............................................................................................................................................... -

Rail Lincs 67

Has Grantham event delivered a rail asset? The visit of record breaking steam locomotive, A4 pacific Mallard, to Grantham at the RailRail LincsLincs beginning of September, has been hailed an outstanding success by the organisers. Number 67 = October 2013 = ISSN 1350-0031 LINCOLNSHIRE With major sponsorship from Lincolnshire County Council, South Kesteven District Lincolnshire & South Humberside Branch of the Council and Carillion Rail; good weather and free admission, the event gave Grantham Railway Development Society N e w s l e t t e r high profile media interest, attracting in excess of 15,000 visitors (some five times the original estimate). Branch has a busy weekend at One noticeable achievement has been the reconstruction of a siding resulting in the clearing of an ‘eyesore’ piece of land at Grantham station, which forms a gateway to the Grantham Rail Show town. The success of the weekend has encouraged the idea for a similar heritage event Thank you to everyone who helped us The weekend was also a very in the future. over the Grantham Rail Show weekend. successful fund raising event which has However, when the piece of land was cleared and the Up side siding reinstated, it This year, the Rail Show was held in left our stock of donated items very became apparent that Grantham had, possibly, unintentionally received a valuable association with the Mallard Festival of depleted. If you have any unwanted items commercial railway asset. Here is a siding connected to the national rail network with Speed event at Grantham station, with a that we could sell at future events, we easy road level access only yards from main roads, forming the ideal location for a small free vintage bus service linking the two would like to hear from you. -

Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. 1St

Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. 1st Generation DMU’s for British Railways A Review Rodger P. Bradley Gloucester RC&W Co.’s Diesel Multiple Units Rodger P Bradley As we know the history of the design and operation of diesel – or is it oil-engine powered? – multiple unit trains can be traced back well beyond nationalisation in 1948, although their use was not widespread in Britain until the mid 1950s. Today, we can see their most recent developments in the fixed formation sets operated over long distance routes on today’s networks, such as those of the Virgin Voyager design. It can be argued that the real ancestry can be seen in such as the experimental Michelin railcar and the Beardmore 3-car unit for the LMS in the 1930s, and the various streamlined GWR railcars of the same period. Whilst the idea of a self-propelled passenger vehicle, in the shape of numerous steam rail motors, was adopted by a number of the pre- grouping companies from around the turn of the 19th/20th century. (The earliest steam motor coach can be traced to 1847 – at the height of the so-called to modernise the rail network and its stock. ‘Railway Mania’.). However, perhaps in some ways surprisingly, the opportunity was not taken to introduce any new First of the “modern” multiple unit designs were techniques in design or construction methods, and built at Derby Works and introduced in 1954, as the majority of the early types were built on a the ‘lightweight’ series, and until 1956, only BR and traditional 57ft 0ins underframe. -

Firstgroup Vies with Virgin in West Coast Rail Bidding War | Business | Guardian.Co.Uk Page 1 of 2

FirstGroup vies with Virgin in west coast rail bidding war | Business | guardian.co.uk Page 1 of 2 Printing sponsored by: FirstGroup vies with Virgin in west coast rail bidding war Aberdeen-based group is frontrunner, along with incumbent, in battle to secure 14-year franchise contract Dan Milmo, industrial editor guardian.co.uk, Sunday 15 July 2012 14.13 BST Virgin, the current holders of the west coast franchise, pay an annual premium of £150m to the government. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian FirstGroup has emerged as a frontrunner for the multibillion-pound west coast rail franchise alongside incumbent Virgin Trains, with the contest now a two-horse race between the experienced operators. Aberdeen-based FirstGroup is vying with Virgin despite announcing last year that it is handing back its Great Western rail contract three years ahead of schedule, avoiding more than £800m in payments to the government. The Department for Transport is expected to bank a considerable windfall from the new 14-year west coast contract, with Virgin currently paying an annual premium of about £150m to the state. Both bidders are expected to promise an even bigger number over the life of the new franchise. The winner is expected to be announced next month. It is understood that FirstGroup and Virgin are still in talks with the DfT, but two foreign-owned bidders on the four-strong shortlist are no longer considered likely contenders. They are a joint venture between public transport operator Keolis and SNCF, the French state rail group, and a bid from Abellio, which is controlled by the Dutch national rail operator. -

Review of the Economic Case for HS2 Economic Evaluation London – West Midlands Link

Review of the Economic Case for HS2 Economic evaluation London – West Midlands link Chris Castles & David Parish November 2011 The Royal Automobile Club Foundation for Motoring Ltd is a charity which explores the economic, mobility, safety and environmental issues relating to roads and responsible road users. Independent and authoritative research, carried out for the public benefit, is central to the Foundation’s activities. RAC Foundation 89–91 Pall Mall London SW1Y 5HS Tel no: 020 7747 3445 www.racfoundation.org Registered Charity No. 1002705 November 2011 © Copyright Royal Automobile Club Foundation for Motoring Ltd Although not commissioned by the RAC Foundation, this report has been published to inform wider debate about the issue. The report content reflects the views of the authors. Review of the Economic Case for HS2 Economic evaluation London – West Midlands link Chris Castles & David Parish November 2011 About the authors Chris Castles is a transport economist and former partner of PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers), where he led the firm’s transport economics and policy group for some fifteen years. He began his career in transport planning working on cost–benefit analysis using transport network models. He joined Coopers & Lybrand where he carried out a wide range of international transport project appraisals for major port, rail, road and airport schemes. He has also undertaken various transport policy studies including studies on the structure of rail freight subsidy, competition within the rail industry, access arrangements and -

Firstgroup Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Contents

FirstGroup plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Contents Strategic report Summary of the year and financial highlights 02 Chairman’s statement 04 Group overview 06 Chief Executive’s strategic review 08 The world we live in 10 Business model 12 Strategic objectives 14 Key performance indicators 16 Business review 20 Corporate responsibility 40 Principal risks and uncertainties 44 Operating and financial review 50 Governance Board of Directors 56 Corporate governance report 58 Directors’ remuneration report 76 Other statutory information 101 Financial statements Consolidated income statement 106 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 107 Consolidated balance sheet 108 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 109 Consolidated cash flow statement 110 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 111 Independent auditor’s report 160 Group financial summary 164 Company balance sheet 165 Notes to the Company financial statements 166 Shareholder information 174 Financial calendar 175 Glossary 176 FirstGroup plc is the leading transport operator in the UK and North America. With approximately £6 billion in revenues and around 110,000 employees, we transported around 2.4 billion passengers last year. In this Annual Report for the year to 31 March 2015 we review our performance and plans in line with our strategic objectives, focusing on the progress we have made with our multi-year transformation programme, which will deliver sustainable improvements in shareholder value. FirstGroup Annual Report and Accounts 2015 01 Summary of the year and -

DEVELOPMENT POLICY COMMITTEE 5 March 2015

DEVELOPMENT POLICY COMMITTEE 5 March 2015 AGENDA ITEM 11 Subject DEPARTMENT FOR TRANSPORT (RAIL EXECUTIVE) - EAST ANGLIA RAIL FRANCHISE CONSULTATION Report by DIRECTOR OF SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES Enquiries contact: Jeremy Potter – Senior Planning Officer 01245 606821 [email protected] Purpose The purpose of this report is to seek the Committee’s approval for the proposed responses to the Department for Transport (DfT) East Anglia Rail Franchise Consultation. Recommendation(s) 1. That the Committee approves the consultation responses to Department for Transport (DfT) East Anglia Rail Franchise Consultation set out at Appendix 1. Corporate Implications Legal: None Financial: None Personnel: None Risk Management: None Equalities and Diversity: None Health and Safety: None IT: None Other: This consultation seeks feedback on the future of rail services in East Anglia which will be the subject of an award of a new Franchise agreement. The extent of improvements in railway services and capacity within Chelmsford City Council’s area has wide-ranging implications for existing communities and businesses. Consultees CCC – Sustainable Communities Directorate 1 Policies and Strategies The report takes into account the following policies and strategies of the Council: Local Development Framework (LDF) Documents Core Strategy and Development Control Policies - Adopted DPD Focused Review of Core Strategy and Development Control Policies – Adopted DPD Chelmsford Town Centre Area Action Plan - Adopted DPD North Chelmsford Area Action Plan – Adopted DPD Site Allocations Development Plan Document – Adopted DPD Local Development Scheme, Third Review March 2013 Planning Obligations SPD – Adopted SPD Community Infrastructure Levy Charging Schedule - February 2014 Duty to Co-operate Strategy, March 2014 The Chelmsford Local Development Framework takes into account all published strategies of the City Council, together with the Sustainable Community Strategy published by The Chelmsford Partnership. -

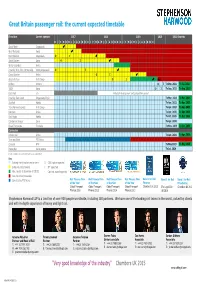

Great Britain Passenger Rail: the Current Expected Timetable

Great Britain passenger rail: the current expected timetable Franchise Current operator 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Onwards DJFMA MJJASONDJFMA MJJASONDJFMA MJJASOND South West Stagecoach West Midlands Govia East Midlands Stagecoach O I South Eastern Govia O I Wales & Borders Arriva InterCity W.C./W.C. Partnership Virgin/Stagecoach O I Cross Country Arriva OI Great Western First Group OI Apr. Chiltern Chiltern OITo Dec. 2021 To Jul. 2022 TSGN Govia O I To Sep. 2021 To Sep. 2023 East West n/a Potential development and competition period InterCity East Coast Stagecoach/Virgin To Mar. 2023 To Mar. 2024 ScotRail Abellio To Apr. 2022 To Apr. 2025 TransPennine Express First Group To Apr. 2023 To Apr. 2025 Northern Arriva To Apr. 2025 To Apr. 2026 East Anglia Abellio To Oct. 2025 To Oct. 2026 Caledonian Sleeper Serco To Apr. 2030 Essex Thameside Trenitalia To Nov. 2029 To Jun. 2030 Concession London Rail Arriva To Apr. 2024 To Apr. 2026 Tyne and Wear PTE Nexus Crossrail MTR To May 2023 To May 2025 MerseyRail Serco/Abellio To Jul. 2028 Based on publicly available information as at 1 April 2017 Key Existing franchise/concession term O OJEU notice expected Extension/direct award I ITT expected Max. length at discretion of DfT/TS Contract award expected New franchise/concession Operated by PTE Nexus Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Band 1 for Rail Band 1 for Rail Band 1 for Rail of the Year of the Year of the Year of the Year Finance Franchising Global Transport Global Transport Global Transport Global Transport Chambers UK 2015 The Legal 500 Chambers UK 2017 Finance 2016 Finance 2015 Finance 2014 Finance 2013 UK 2016 Stephenson Harwood LLP is a law firm of over 900 people worldwide, including 150 partners. -

NS Annual Report 2018

See www.nsannualreport.nl for the online version NS Annual Report 2018 Table of contents 2 In brief 4 2018 in a nutshell 8 Foreword by the CEO 12 The profile of NS 16 Our strategy Activities in the Netherlands 23 Results for 2018 27 The train journey experience 35 Operational performance 47 World-class stations Operations abroad 54 Abellio 56 Strategy 58 Abellio United Kingdom (UK) 68 Abellio Germany 74 Looking ahead NS Group 81 Report by the Supervisory Board 94 Corporate governance 100 Organisation of risk management 114 Finances in brief 126 Our impact on the environment and on society 134 NS as an employer in the Netherlands 139 Organisational improvements 145 Dialogue with our stakeholders 164 Scope and reporting criteria Financial statements 168 Financial statements 238 Company financial statements Other information 245 Combined independent auditor’s report on the financial statements and sustainability information 256 NS ten-year summary This annual report is published both Dutch and English. In the event of any discrepancies between the Dutch and English version, the Dutch version will prevail. 1 NS annual report 2018 In brief More satisfied 4.2 million trips by NS app gets seat passengers in the OV-fiets searcher Netherlands (2017: 3.1 million) On some routes, 86% gave travelling by passengers can see which train a score of 7 out of carriages have free seats 10 or higher Customer 95.1% chance of Clean trains: 68% of satisfaction with HSL getting a seat passengers gave a South score of 7 out of 10 (2017: 95.0%) or higher 83% of -

Scotrail Franchise – Franchise Agreement

ScotRail Franchise – Franchise Agreement THE SCOTTISH MINISTERS and ABELLIO SCOTRAIL LIMITED SCOTRAIL FRANCHISE AGREEMENT 6453447-13 ScotRail Franchise – Franchise Agreement TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Interpretation and Definitions .................................................................................... 1 2. Commencement .......................................................................................................... 2 3. Term ............................................................................................................ 3 4 Franchisee’s Obligations ........................................................................................... 3 5 Unjustified Enrichment ............................................................................................... 4 6 Arm's Length Dealings ............................................................................................... 4 7 Compliance with Laws................................................................................................ 4 8 Entire Agreement ........................................................................................................ 4 9 Governing Law ............................................................................................................ 5 SCHEDULE 1 ............................................................................................................ 7 PASSENGER SERVICE OBLIGATIONS ............................................................................................. 7 SCHEDULE 1.1 ...........................................................................................................