Hampton Square Between the Wars Hampton Square Between the Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

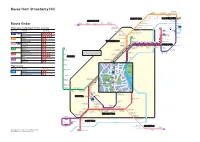

Buses from Strawberry Hill

Buses from Strawberry Hill Hammersmith Stamford Brook Hammersmith Grove Gunnersbury Bus Garage for Hammersmith & City line Turnham Green Ravenscourt Church Park Kew Bridge for Steam Museum 24 hour Brentford Watermans Arts Centre HAMMERSMITH 33 service BRENTFORD Hammersmith 267 Brentford Half Acre Bus Station for District and Piccadilly lines HOUNSLOW Syon Park Hounslow Hounslow Whitton Whitton Road River Thames Bus Station Treaty Centre Hounslow Church Admiral Nelson Isleworth Busch Corner 24 hour Route finder 281 service West Middlesex University Hospital Castelnau Isleworth War Memorial N22 Twickenham Barnes continues to Rugby Ground R68 Bridge Day buses including 24-hour services Isleworth Library Kew Piccadilly Retail Park Circus Bus route Towards Bus stops London Road Ivy Bridge Barnes Whitton Road Mortlake Red Lion Chudleigh Road London Road Hill View Road 24 hour service ,sl ,sm ,sn ,sp ,sz 33 Fulwell London Road Whitton Road R70 Richmond Whitton Road Manor Circus ,se ,sf ,sh ,sj ,sk Heatham House for North Sheen Hammersmith 290 Twickenham Barnes Fulwell ,gb ,sc Twickenham Rugby Tavern Richmond 267 Lower Mortlake Road Hammersmith ,ga ,sd TWICKENHAM Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Twickenham Lebanon Court Crown Road Cresswell Road 24 hour Police Station 281 service Hounslow ,ga ,sd Twickenham RICHMOND Barnes Common Tolworth ,gb ,sc King Street Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Orleans Park School St Stephen’s George Street Twickenham Church Richmond 290 Sheen Road Staines ,gb ,sc Staines York Street East Sheen 290 Bus Station Heath Road Sheen Lane for Copthall Gardens Mortlake Twickenham ,ga ,sd The yellow tinted area includes every Sheen Road bus stop up to about one-and-a-half Cross Deep Queens Road for miles from Strawberry Hill. -

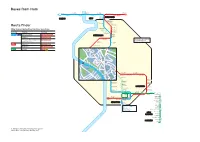

Buses from Ham

Buses from Ham Brentford Kew Road Kew Gardens North Sheen Ealing Broadway Waterman’s Arts Centre Mortlake Road Lion Gate Richmond Circus Sainsbury’s 24 hour service 371 65 South Ealing Kew Bridge Kew Gardens Lower Mortlake Road Manor Circus for Steam Museum Victoria Gate Richmond Richmond RICHMOND George Street EALING KEW Richmond Bus Station Church Road St Mattias Church Richmond Petersham Road King’s Road Hill Rise Route finder Marchmont Road Queen’s Road Petersham Road Park Road Compass Hill Day buses including 24-hour services Queen’s Road Petersham Road Chisholm Road Robins Court Bus route Towards Bus stops Queen’s Road Petersham Road American University Nightingale Lane 24 hour Petersham service Ealing Broadway ,f ,g ,h ,j ,k,l The Dysart 65 PETERSHAM Petersham Fox & Duck Kingston ,a ,b ,c ,d ,e River Thames Sandy Lane The yellow tinted area includes every Clifford Road Chessington World of Adventures ,a ,b ,c ,d ,e bus stop up to about one-and-a-half miles from Ham. Main stops Sandy Lane (Night journeys only) are shown in the white area outside. Ham Street Petersham Road Sandy Lane D Kingston ,m ,n ,p ,q ,r OA R 371 M M AshburnhamA Road A H R B N T I N IS R GALES H U CL O B O PS H ,s ,t ,u ,v ,w,x S S C Richmond L A E S H R T B A E A R Convent N C E M CO Richmond I S E M e M R K M O N T A N A L D H ,p ,q B M G A Golf Course Morden N H&R q R f E T R K5 A M E O F W E I L Meadlands L L U C L K G L H O A BR O H O Z M T S Primary GA E T ON H E A D A VE School A N M UE O E A R IV V K C C C Ham R E O R O D L M N L A CH I R N U A G M R Common E O U W CH S R H O P E R OA S R N H D O I M D I E A F S A g N A O G M R p C D N E I F d A K D R R O A M A R D O R IV ERS O E IDE DRIV R A D D U ̄ K The Cassel M ES Hospital A Teddington A H D VE i A N R Lock O M AG U E PARKLEY R UI E S T RE P R c P O F o U U A D R E L I V [ B AM E B M E AR A U j NF B S N IE U R E TU LD RN OA V r DO AV EL D A R EN Footbridge L T n DR U A R IV E V E E EN A D U S N R E ̃ Y A L A D Y D R R R L T A \ U E B A F E RO DO U G W C GH St. -

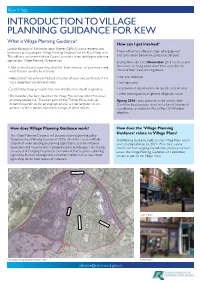

What Is Village Planning Guidance?

Kew Village INTRODUCTION TO VILLAGE PLANNING GUIDANCE FOR KEW What is Village Planning Guidance? How can I get involved? London Borough of Richmond upon Thames (LBRuT) wants residents and businesses to help prepare ‘Village Planning Guidance’ for the Kew Village area. There will be two different stages of engagement This will be a document that the Council considers when deciding on planning and consultation before the guidance is adopted. applications. Village Planning Guidance can: During November and December 2013 residents and • Help to identify, with your help, what the ‘local character’ of your area is and businesses are being asked about their vision for the what features need to be retained. future of their areas, thinking about: • Help protect and enhance the local character of your area, particularly if it is • the local character not a designated ‘conservation area’. • heritage assets • Establish key design principles that new development should respond to. • improvement opportunities for specific sites or areas • other planning policy or general village plan issues • The boundary has been based on the Village Plan area to reflect the views of where people live. The open parts of the Thames Policy Area (as Spring 2014 - draft guidance will be written after denoted in purple on the photograph below) will not form part of the Christmas based on your views and a formal (statutory) guidance as this is already covered by a range of other policies. consultation carried out in March/April 2014 before adoption. How does Village Planning Guidance work? How does the ‘Village Planning Guidance’ relate to Village Plans? The Village Planning Guidance will become a formal planning policy ‘Supplementary Planning Document’ (SPD) which the council will take The Planning Guidance builds on the ‘Village Plans’ which account of when deciding on planning applications, so it will influence were developed from the 2010 ‘All in One’ survey developers and householders in preparing plans and designs. -

Second Local Implementation Plan

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames SECOND LOCAL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Overview............................................................................................. 6 1.1 Richmond in Context............................................................................................. 6 1.2 Richmond’s Environment...................................................................................... 8 1.3 Richmond’s People............................................................................................... 9 1.4 Richmond’s Economy ......................................................................................... 10 1.5 Transport in Richmond........................................................................................ 11 1.5.1 Road ................................................................................................................... 11 1.5.2 Rail and Underground......................................................................................... 12 1.5.3 Buses.................................................................................................................. 13 1.5.4 Cycles ................................................................................................................. 14 1.5.5 Walking ............................................................................................................... 15 1.5.6 Bridges and Structures ....................................................................................... 15 1.5.7 Noise -

Richmond Gardens

CHISWICK TURNHAM CONNECTIONS PARK GREEN KENSINGTON M4 Junction 2, OLYMPIA M4 KEW RICHMOND BOSTON A315 Living at Richmond Gardens gives you the RICHMO ND BRIDGE HAMMERSMITH WEST MANOR GUNNERSBURY GARDENS KENSINGTON choice of Underground, Overground or GARDRICHMONDEN UPON THAMESS A4 FULHAM mainline rail travel. North Sheen station is BRENTFORD 6 A3218 CHISWICK A31 just a seven minute walk away, where direct RICHMOND UPON THAMES A315 KEW A306 FULHAM SYON LANE BROADWAY trains to London Waterloo take 25 minutes. Richmond station, which is just a two KEW A205 BARNES D CHERTSEY ROAD PARSONS ISLEWORTH ROYAL BRIDGE minute train journey in the other direction, ROA GREEN BOTANIC W B353 MORTLAKE BARNES serves the Underground’s District line into GARDENS KE BARNES PUTNEY R RICHMOND RD central London as well as the Overground, LOWE BRIDGE UPPER RICHMOND ROAD A205 A305 PUTNEY which loops across north London via A316RICHMOND NORNORTHORRTRT Hampstead to Stratford. SHEESHEEN SANDYCOMBE RD EAST A3 Frequent bus services along Lower To Kew Bridge PUTNEY & J2, M4 Richmond Road also take you into A306 Richmond, while Heathrow Airport is To Richmond To Chiswick Bridge A316 RICHMOND PARK 7.3 miles by car. LOWER LOWER RICHMOND RD A316 A3 MARKET ROAD ORCHARD RD MORTLAKE RD A218 MANOR ROAD GARDEN RD D RICHMO ND KINGSDON ROA Travel times* from Richmond station: GARDENS WIMBLEDON MANOR GROVE A219 PARK WIMBLEDON Kew Gardens 3 minutes To Richmond Park B353 NORTH SHEEN COMMON Teddington 11 minutes A308 Clapham Junction 8 minutes A3 Waterloo 19 minutes RICHMOND GARDENS, GARDEN ROAD, Victoria (via Clapham Junction) 20 minutes RICHMOND UPON THAMES, TW9 4NR West Hampstead 26 minutes Paddington 37 minutes Bank 38 minutes Heathrow 51 minutes Stratford 58 minutes *www.tfl.gov.uk For further information please call: 0844 809 2018 www.richmond-gardens.co.uk The information in this document is indicative and intended to act as a guide only as to the finished product. -

London Borough of Richmond Upon Thames Third Local Implementation Plan

Official London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Third Local Implementation Plan November 2018 Draft for consultation Official Table of Contents 1. Introduction and preparing a LIP 4 Introduction 4 Local approval process 4 2. Borough Transport Objectives 5 Introduction 5 Local context 5 Changing the transport mix 10 Mayor’s Transport Strategy outcomes 14 Outcome 1: London’s streets will be healthy and more Londoners will travel actively 14 Outcome 2: London’s streets will be safe and secure 19 Outcome 3: London’s streets will be used more efficiently and have less traffic on them 22 Outcome 4: London’s streets will be clean and green 25 Outcome 5: The public transport network will meet the needs of a growing London 26 Outcome 6: Public transport will be safe, affordable and accessible to all 29 Outcome 7: Journeys by public transport will be pleasant, fast and reliable 30 Outcome 8: Active, efficient and sustainable travel will be the best option in new developments 32 Outcome 9: Transport investment will unlock the delivery of new homes and jobs 33 Other Mayoral Strategies 33 3. The Delivery Plan 36 Introduction 36 2 Official Linkages to the Mayor’s Transport Strategy priorities 36 TfL Business Plan 40 Sources of funding 41 Long-Term interventions to 2041 43 Three-year indicative Programme of Investment 46 Supporting commentary for the three-year programme 47 Risks to the delivery of the three-year programme 48 Annual programme of schemes and initiatives 51 Supporting commentary for the annual programme 51 Risk assessment for the annual programme 52 Monitoring the delivery of the outcomes of the Mayor’s Transport Strategy 55 Overarching mode-share aim and outcome Indicators 55 Delivery indicators 55 Local targets 55 Appendix 1: Summary of Annual Spending Submission to TfL 61 3 Official 1. -

Infrastructure Delivery Schedule and Draft Regulation 123 List May 2013

Local Plan INFRASTRUCTURE DELIVERY SCHEDULE & DRAFT REGULATION 123 LIST Version to accompany Community Infrastructure Levy Draft Charging Schedule consultation 8 July to 19 August 2013 May 2013 LBRuT Infrastructure Delivery Schedule and draft Regulation 123 List May 2013 Contents 1 Introduction............................................................................................. 4 2 Scope of the infrastructure evidence base for CIL ............................. 4 3 Methodology and stages ....................................................................... 5 4 Stakeholder consultation....................................................................... 6 5 Detailed Infrastructure Delivery Schedule ........................................... 7 5.1 Transport, including walking & cycling.........................................................7 5.2 Education .......................................................................................................12 5.3 Community facilities and libraries ...............................................................14 5.4 Parks, open spaces and playgrounds .........................................................14 5.5 Health..............................................................................................................15 5.6 Waste facilities...............................................................................................16 5.7 Sport facilities ................................................................................................17 6 Aggregate -

Buses from Teddington

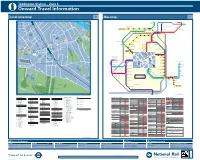

Teddington Station – Zone 6 i Onward Travel Information Local area map Bus mapBuses from Teddington 36 R A 117 20 I L C W 1 R O V E A E G G 95 T H R O V E G A R 19 H Y 45 49 R 30 58 99 88 ELMTREE ROAD U O 481 33 88 Teddington A D River Thames R D 23 ENS West Middlesex 95 Hammersmith 84 Lock C 156 21 23 Bowling University Hospital CLAREMONT ROAD Bus Station 98 149 H Green R68 81 25 T H E G R O V E Kew R 48 147 O Footbridge 1 Retail Park 93 145 4 77 TEDDINGTON PARK ROAD 85 A VICTOR ROAD Maddison TEDDINGTON PARK S E N 80 D Footbridges R 41 86 D Centre 32 A Castelnau G 88 V E 30 141 O G R HOUNSLOW Richmond RICHMOND 1 10 79 C N A Twickenham Teddington LINDEN GROVE M Lower Mortlake Road 57 B Barnes 73 R Hounslow Whitton Whitton Tesco 95 Social Club I E D H A L L C O U R T 24 L G Red Lion E 33 Treaty Centre Church M L Hounslow Admiral Nelson 44 84 12 C M 100 R T 73 E O H 28 R S A C 58 R E O 17 A E T R O A D L D I 116 E B 281 C R Hounslow Twickenham Richmond 56 ELMFIELD AVENUE E 63 44 R S T N 105 27 O I N 29 8 SOMERS 82 T M Twickenham A 7 S O Bus Station Stadium E M A N O R R O A D D BARNES W 59 31 14 61 R Barnes RAILWAY ROAD 28 56 4 13 52 17 TWICKENHAM ROAD R Twickenham 95 D SOMERSET GARDENS B A The HENRY PETERS L O O 106 TEDDINGTON PARKE 77 130 25 N 45 R 4 York Street D H Y Tide End Kneller Road E 50 A R DRIVE CHURCH ROAD I A M 72 R E Cottage O P CAMBRIDGE CRESCENT D F Kneller Hall L 41 R A 32 4 TWICKENHAM Sheen Road East Sheen Barnes Common 41 C S T O K E S M E W S E 4 1 T ST. -

Buses from Ham

Buses from Ham Brentford Ealing South Waterman’s Kew Kew Road Kew Gardens Kew Gardens North Sheen Broadway Ealing Arts Centre Bridge Mortlake Road Victoria Gate Lion Gate Richmond Circus Sainsbury’s 65 Lower Mortlake Road 371 N65 Manor Circus Buses from Ham Richmond Richmond RICHMOND EALING KEW George Street Richmond Bus Station Church Road St. Matthias Church Richmond Brentford PetershamNorth Sheen Road King’s Road Ealing South Waterman’s Kew Kew Road Kew Gardens Kew Gardens Hill Rise Broadway Ealing Arts Centre Bridge Mortlake Road Victoria Gate Lion Gate Richmond Circus Sainsbury’s Marchmont Road 65 Lower Mortlake Road 371 Manor Circus N65 Richmond Petersham Road Queen’s Road Richmond RICHMOND Compass Hill Park Road George Street EALING KEW Richmond Queen’s Road Bus Station Petersham Road Chisholm Road Church Road Robins Court St. Matthias Church Queen’s Road Petersham Road American University Richmond Nightingale Lane King’s Road Petersham Road Petersham Hill Rise The Dysart Marchmont Road PETERSHAM Petersham Fox & Duck Queen’s Road Petersham RoadRiver Thames Sandy Lane Compass Hill Park Road Clifford Road Queen’s Road Petersham Road Chisholm Road Sandy Lane Robins Court Ham Street Queen’s Road Petersham Road Petersham Road American University Sandy Lane Nightingale Lane Petersham Ashburnham Road PETERSHAM The Dysart Petersham ST HA Fox & Duck BACK LANE Convent R M BRO E HA e Richmond ET M COMMON HAM GATE AVENUE Sandy Lane Golf Course River Thames q f Clifford Road F U Meadlands EL G Primary L OK HT O R Z B ON School HA Sandy Lane A E V OAD V EN R M Ham Street RI K D U CRA Ham E C R LOC LAWRE O CHURCH PetershamE Road IG ROAD MMON Common H S R Sandy LaneI PSOND H O F AD A OA g N M SIM R p DU NG CE I FARM d K KES Ashburnham Road R AV OAD R I D VE RO RSIDE DRIVE E A The yellow tinted area includes every The Cassel O A R D bus stop up to about one-and-a-half Hospital ST HA M miles from Ham. -

North Sheen Rec Management Plan 2018-19: Foreword

Official North Sheen Recreation Ground Management Plan January 2018 – December 2019 1 Official North Sheen Rec Management Plan 2018-19: Foreword North Sheen Rec is an important space for local people and visitors. The London Borough of Richmond upon Thames will maintain and manage the park to the highest standards in accordance with our strategic principles and policies. This management plan is based on the use of an audit of the park following central government guidance known as PPG 17. This is explained within this document but the approach is based on common sense. We believe that it is important to get the simple things right. Is the green space clean and tidy? Is the grass cut? Are the trees and shrubs well maintained? Is any graffiti removed effectively and quickly? Working with local communities to deliver the highest quality of service is top priority and it is hoped that this document will provide a framework for continuing and improving dialogue. The site will be maintained appropriately and the local community will be consulted on any proposed changes or improvements to facilities and infrastructure. In particular, the borough works closely with the Friends of North Sheen Rec and Kew Park Ranger Football Club. We actively encourage suggestions about all aspects of the park. Parks Officers, working closely with colleagues in Continental Landscapes and using a partnership approach, regularly monitor the park. Members of the local community are also encouraged to let us know their impressions about the level of maintenance as well as their ideas. It is hoped that the resulting observations and ideas will result in continually improving management and maintenance practises. -

Appendix 1 Study Area and Methodology

Richmond Retail Study Appendix 1 Study Area and Methodology 6765233v5 P43 Richmond Retail Study LB Richmond Study Area Zones Zone Wards 1 South Richmond Ham, Petersham and Richmond Riverside 2 St Margaret’s and North Twickenham Twickenham Riverside South Twickenham 3 Whitton Heathfield West Twickenham 4 Fulwell and Hampton Hill Teddington Hampton Wick 5 Hampton Hampton North 6 Kew North Richmond 7 Mortlake and Barnes Common Barnes East Sheen P44 6765233v5 Richmond Retail Study 6765233v5 P45 Retail Capacity Assessment – Methodology and Data Price Base 1 All monetary values expressed in this study are at 2012 prices, consistent with Experian’s base year expenditure figures for 2012 (Retail Planner Briefing Note 11) which is the most up to date information available. Study Area 2 The quantitative analysis is based on the Borough study area, which covers the primary catchment areas of the five main shopping destinations in LBRuT. The study area is sub-divided into seven zones based on ward boundaries as shown above. The survey zones take into consideration the extent of the catchment area of the main centres in LBRuT. Retail Expenditure 3 The level of available expenditure to support retailers is based on first establishing per capita levels of spending for the study area population. Experian’s local consumer expenditure estimates for comparison and convenience goods for each of the study area zones for the year 2012 have been obtained. 4 Experian’s EBS national expenditure information (Experian Retail Planner Briefing Note 11, September 2013) has been used to forecast expenditure within the study area. Experian’s forecasts are based on an econometric model of disaggregated consumer spending. -

Buses from Strawberry Hill

Strawberry Hill Station – Zone 5 i Onward Travel Information Local area map Bus mapBuses from Strawberry Hill 2 10 1 100 M AY R O A D 65 ANDOVER ROAD 19 LION AVENUE 8 118 Waterstones 100 18 Twickenham 38 1 58 Diamond MEREWAY39 ROAD S 11 S TA B L E M E W 2 51 33 Hammersmith 2 2 Jubilee E D W I N R O A D 2 1 Iceland 102 Gardens D 93 COLLIS ALLEY Stamford Brook Hammersmith GRAVEL ROAD 28 39 W 8 11 H 1 C O L N E R O A 77 Gunnersbury Bus Garage 124 NORTHUMBERLAND ROW C O L N E R O A D 144 A & City line 23 21 86 R 17 6 48 D 13 A F L O A Play Caf H E A T H R R N KNOWLE ROAD 166 O A 149 D H E Area Turnham Green Ravenscourt 50 11 12 111 Sunshine D A D 1 T 33 A 32 7 O A O R H E Cross Deep Surgery R O N 159 85 Church Park R B I COLLIS ALLEY E Kings A L 178 and Medical Centre V ANDOVER ROAD O 2 1 Kew Bridge for Steam Museum D 59 N 87 C O L N E R O A D Arms A 2 96 33 1 19 1 81 KNIGHT’S 1 PLACE 1 6 14 179 49 Brentford Watermans Arts Centre RADNOR ROAD 1 267 G AT EHUNTING M E W S SAVILLE ROAD 1 HEATHLANDS CLOSE 18 20 1 15 Twickenham Green BRENTFORD 180 1 Hammersmith N Baptist Church POULETT GARDENS 19 Brentford County Court 22 B R I A R R O A D 2 Bus Station 133 E N E 25 14 R 37 HOUNSLOW G 12 HAMMERSMITH Syon Park 33 2 4 E 16 Twickenham Green 6 H 51 C A M45 A C R O A D T 24 46 22 Hounslow Hounslow Whitton Whitton 106 17 1 Isleworth Busch Corner River Thames 2 HEATH GARDENS MEADWAY 77 33 Bus Station Treaty Centre Hounslow Church Admiral Nelson 5 TENNYSON AVENUE B 8 25 76 R I POULETT GARDENS N 28 1 33 56 S 7 17 16 281 West Middlesex University Hospital