Medication Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CS/CS/HB 1373 Persons with Developmental Disabilities

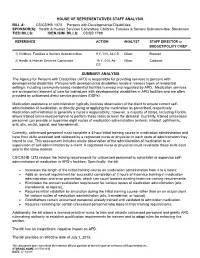

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STAFF ANALYSIS BILL #: CS/CS/HB 1373 Persons with Developmental Disabilities SPONSOR(S): Health & Human Services Committee; Children, Families & Seniors Subcommittee; Stevenson TIED BILLS: IDEN./SIM. BILLS: CS/SB 1788 REFERENCE ACTION ANALYST STAFF DIRECTOR or BUDGET/POLICY CHIEF 1) Children, Families & Seniors Subcommittee 9 Y, 0 N, As CS Gilani Brazzell 2) Health & Human Services Committee 16 Y, 0 N, As Gilani Calamas CS SUMMARY ANALYSIS The Agency for Persons with Disabilities (APD) is responsible for providing services to persons with developmental disabilities. Persons with developmental disabilities reside in various types of residential settings, including community-based residential facilities licensed and regulated by APD. Medication services are an important element of care for individuals with developmental disabilities in APD facilities and are often provided by unlicensed direct service providers (DSPs). Medication assistance or administration typically involves observation of the client to ensure correct self- administration of medication, or directly giving or applying the medication as prescribed, respectively. Medication administration is generally a nurse’s responsibility; however, a majority of states, including Florida, allows trained unlicensed personnel to perform these tasks to meet the demand. Currently, trained unlicensed personnel can provide or supervise eight routes of medication administration (enteral, inhaled, ophthalmic, oral, otic, rectal, topical, and transdermal). Currently, unlicensed personnel must complete a 4-hour initial training course in medication administration and have their skills assessed and validated by a registered nurse or physician in each route of administration they intend to use. This assessment includes onsite observation of the administration of medication to or supervision of self-administration by a client. -

Clinical Practice Statements-Oral Contact Allergy

Clinical Practice Statements-Oral Contact Allergy Subject: Oral Contact Allergy The American Academy of Oral Medicine (AAOM) affirms that oral contact allergy (OCA) is an oral mucosal response that may be associated with materials and substances found in oral hygiene products, common food items, and topically applied agents. The AAOM also affirms that patients with suspected OCA should be referred to the appropriate dental and/or medical health care provider(s) for comprehensive evaluation and management of the condition. Replacement and/or substitution of dental materials should be considered only if (1) a reasonable temporal association has been established between the suspected triggering material and development of clinical signs and/or symptoms, (2) clinical examination supports an association between the suspected triggering material and objective clinical findings, and (3) diagnostic testing (e.g., dermatologic patch testing, skin-prick testing) confirms a hypersensitivity reaction to the suspected offending material. Originators: Dr. Eric T. Stoopler, DMD, FDS RCSEd, FDS RCSEng, Dr. Scott S. De Rossi, DMD. This Clinical Practice Statement was developed as an educational tool based on expert consensus of the American Academy of Oral Medicine (AAOM) leadership. Readers are encouraged to consider the recommendations in the context of their specific clinical situation, and consult, when appropriate, other sources of clinical, scientific, or regulatory information prior to making a treatment decision. Originator: Dr. Eric T. Stoopler, DMD, FDS RCSEd, FDS RCSEng, Dr. Scott S. De Rossi, DMD Review: AAOM Education Committee Approval: AAOM Executive Committee Adopted: October 17, 2015 Updated: February 5, 2016 Purpose The AAOM affirms that oral contact allergy (OCA) is an oral mucosal response that may be associated with materials and substances found in oral hygiene products, common food items, and topically applied agents. -

Topical Medication Administration

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Medication Administration Assessment for Topical Medication Administration Name: ____________________________________________ Please circle the correct answer and take the completed test to the school nurse or school district administrator for scoring. 1. Which of the following is not a common form of topical skin medication administration in schools? a. Ointment b. Patches c. Solutions d. Gelatin 2. Which of the following is not considered one of the five rights or guidelines to administer medications? a. Right time b. Right drug c. Right location d. Right route 3. What is the most correct sequence of event for administration of a topical medicated patch? a. Wash hands and apply gloves, check the 5 rights, write date, time and initials on patch, open package and apply medicated patch, remove gloves and record on medication administration record. b. Apply gloves, check the 4 rights, open package and apply medicated patch, write date, time and initials on patch, remove gloves and wash hands, and record on medication administration record. c. Record on medication administration record, wash hands and apply gloves, check the first 5 rights, open package and apply medicated patch, write date, time and initials on patch, remove gloves and wash hands. d. Wash hands and apply gloves, check the 5 rights, open package and apply medicated patch, write date, time and initials on patch, remove gloves and wash hands and record on medication administration record. WI DPI 07/06/2016 Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Medication Administration 4. It is important to report to the school nurse or parent any signs of skin irritation. -

The Effect of Diclofenac Mouthwash on Periodontal Postoperative Pain

Original Article The Effect of Diclofenac Mouthwash on Periodontal Postoperative Pain Jaber Yaghini1, Ahmad Moghareh Abed2, Seyed Abolfazl Mostafavi3, Najmeh Roshanzamir4 ABSTRACT Background: The need to relieve pain and inflammation after periodontal surgery and the side effects of systemic drugs and advantages of topical drugs, made us to evaluate the effect of Diclofenac mouthwash on periodontal postoperative pain. Methods: In this double-blind, randomized clinical trial study 20 quadrants of 10 patients(n = 20) aged between 22-54 who also acted as their own controls, were treated using Modified Widman Flap procedure in two quadrants of the same jaw with one month interval between the operations. After the operation in addition to ibuprofen 400 mg, one quadrant randomly received Diclofenac mouthwash (0/01%) for 30 seconds, 4 times a day (for a week) and for the contrary quadrant, ibupro- fen and placebo mouthwash was given to be used in the same manner. The patients scored the num- ber of ibuprofen consumption and their pain intensity based on VAS index in a questionnaire in days 1, 2, 3 and the first week after operation. The findings were analysed using two-way ANOVA, t-test and Wilcoxon. P-value less than 0.05 considered to be significant. Results: There was a significant difference between the mean values of pain intensity of two quad- rants in four periods (P = 0.031). But, there was no significant difference between the average ibupro- fen consumption in two groups (P = 0.51). Postoperative satisfaction was not significantly different in two quadrants (P = 0.059). 60% of patients preferred Diclofenac mouthwash. -

Topical Treatments of Skin Pain Associated with Hidradenitis Supprurativa

UC Davis Dermatology Online Journal Title Topical treatments of skin pain: a general review with a focus on hidradenitis suppurativa with topical agents Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4m57506k Journal Dermatology Online Journal, 20(7) Author Scheinfeld, Noah Publication Date 2014 DOI 10.5070/D3207023131 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Volume 20 Number 7 July 2014 Review Topical treatments of skin pain: a general review with a focus on hidradenitis suppurativa with topical agents Noah Scheinfeld MD JD Dermatology Online Journal 20 (7): 3 Assistant Clinical Professor of Dermatology Weil Cornel Medical College Correspondence: Noah Scheinfeld 150 West 55th Street NYC NY 10019 (212) 991-6490 [email protected] Abstract Hidradenitis Supprurativa (HS) is a painful chronic follicular disease. Few papers have addressed pain control for this debilitating condition. Possible topical agents include tricyclic antidepressants, opioids, anticonvulsants, NSAIDs, NMDA receptor antagonists, local anesthetics and other agents. The first line agents for the topical treatment of the cutaneous pain of HS are diclonefac gel 1% and liposomal xylocaine 4% and 5% cream or 5% ointment. The chief advantage of topical xylocaine is that is quick acting i.e. immediate however with a limited duration of effect 1-2 hours. The use of topical ketamine, which blocks n- methyl-D-aspartate receptors in a non-competitive fashion, might be a useful tool for the treatment of HS pain. Topical doxepin, which available in a 5% commercially preparation (Zonalon®) , makes patients drowsy and is not useful for controlling the pain of HS . -

Clinical Effectiveness of Compounded Topical Medications in Oral Medicine: a Meta-Analysis

Margono et al. Stomatological Dis Sci 2020;4:3 Stomatological DOI: 10.20517/2573-0002.2019.18 Disease and Science Meta-Analysis Open Access Clinical effectiveness of compounded topical medications in oral medicine: a meta-analysis Her Basuki Margono1, Irna Sufiawati2 1Oral Medicine Residency Program, Faculty of Dentistry, Padjadjaran University, Bandung 40132, West Java, Indonesia. 2Department of Oral Medicine, Faculty of Dentistry, Padjadjaran University, Bandung 40132, West Java, Indonesia. Correspondence to: Dr. Irna Sufiawati, Department of Oral Medicine, Faculty of Dentistry, Padjadjaran University: Jl. Sekeloa Selatan I, Bandung 40132, West Java, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] How to cite this article: Margono HB, Sufiawati I. Clinical effectiveness of compounded topical medications in oral medicine: a meta-analysis. Stomatological Dis Sci 2020;4:3. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2573-0002.2019.18 Received: 16 Oct 2019 First Decision: 11 Nov 2019 Revised: 14 May 2020 Accepted: 21 Jul 2020 Published: 19 Aug 2020 Academic Editor: Letizia Perillo Copy Editor: Cai-Hong Wang Production Editor: Jing Yu Abstract Aim: To assess the evidence of the efficacy and safety of compounded topical medications in oral medicine cases. Methods: Electronic databases were searched from inception to October 2019 for studies that evaluated compounded topical medications in oral medicine cases to assess their efficacy and safety. Search terms included drug compounding, topical administration, clinical efficacy, and oral lesions. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or cross-over trials of compounded topical drug versus non-compounded drug or placebo or standard treatment were included. The exclusion criteria included compounded topical medications with herbal ingredients in the intervention group to compare with the non-compounded drug. -

Short-Contact Clobetasol Propionate Shampoo 0.05% Improves Quality of Life in Patients with Scalp Psoriasis

THERAPEUTICS FOR THE CLINICIAN Short-Contact Clobetasol Propionate Shampoo 0.05% Improves Quality of Life in Patients With Scalp Psoriasis Jerry Tan, MD, FRCPC; Richard Thomas, MD; Béatrice Wang, MD; David Gratton, MD; Ronald Vender, MD; Nabil Kerrouche, MSc; Hervé Villemagne, MSc; for the CalePso Study Team Scalp psoriasis has a considerable impact on the on their QOL increased from 45.6% at baseline to quality of life (QOL) of patients, and most patients 81.7% at week 4. Most participants were satisfied are dissatisfied with available treatments. Clo- with the cosmetic acceptability and the efficacy betasol propionate shampoo 0.05% has been and safety aspects of the product, considered shown to be effective and safe for moderate to it better than prior treatments, and would use it severe scalp psoriasis. We evaluated the effect again in the future. Therefore, we conclude that of clobetasol propionate shampoo on QOL and treatment with clobetasol propionate shampoo the degree of participant satisfaction with the improved the QOL of participants and resulted in product. Participants received once-daily treat- high satisfaction. ment for up to 4 weeks. Their QOL and degree Cutis. 2009;83:157-164. of satisfaction were evaluated by questionnaires. The mean (standard deviation) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score decreased signifi- calp psoriasis is a common inflammatory disease cantly from 7.0 (4.9) at baseline to 3.2 (3.2) at that has a considerable impact on the quality of week 4 (P,.001). Participants who considered S life (QOL) of patients because of its associated the disease as having a small effect or no effect pruritus, the visibility of lesions, and the chronicity of disease.1 Approximately 50% of patients in one Accepted for publication January 26, 2009. -

Simple Water Based Tacrolimus Enemas for Refractory Proctitis

doi:10.1002/jgh3.12280 LEADING ARTICLE Simple water-based tacrolimus enemas for refractory proctitis Sasha R. Fehily,* Felicity C. Martin* and Michael A. Kamm*,† *Department of Gastroenterology, St Vincent’s Hospital and †University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Key words Abstract basic science, endoscopy, experimental models Background and Aims: Rectal ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease and pathophysiology, pathology. (CD) often do not respond to conventional therapies. Oral and suppository tacrolimus are effective but often poorly tolerated or are complex to formulate. Tacrolimus is top- Accepted for publication 31 October 2019. ically active, water soluble, and has minimal systemic toxicity when administered rec- Correspondence tally; we therefore tested a simple tap water-based enema formulation. Professor Michael A Kamm, St Vincent’s Hospital, Methods: Tacrolimus powder from 1 mg capsules and tap water in a 60 mL syringe Victoria Parade, Fitzroy, Melbourne, Vic. 3065, were delivered rectally. The primary end-point was endoscopic response (UC: MAYO Australia. score reduction by one point; CD: improvement in ulcer number and severity). Sec- Email: [email protected] ondary end-points included endoscopic remission, clinical response, stool frequency, and rectal bleeding. Declaration of conflict of interest: None. Results: Seventeen patients [12 UC, five CD, nine female, median age 31 years] with refractory rectal disease were treated. The majority of patients had failed immunosup- pressive therapy [88% thiopurine; 71% biologic therapy]. Initial enemas included 1–4 mg tacrolimus daily and 1–3 mg tacrolimus maintenance three times a week for a median of 20 weeks (range 3–204). Concomitant thiopurine or biologic therapy con- tinued. -

On Letterhead

STATE OF MICHIGAN GRETCHEN WHITMER DEPARTMENT OF LICENSING AND REGULATORY AFFAIRS ORLENE HAWKS GOVERNOR DIRECTOR LANSING May 30, 2019 Marcia Curtiss Lifehouse Crystal Manor Operations LLC Suite 115 21800 Haggerty Rd. Northville, MI 48167 RE: License #: AL410302931 Investigation #: 2019A0340031 Addington Place of Grand Rapids Seaside Dear Mrs. Curtiss: Attached is the Special Investigation Report for the above referenced facility. Due to the violations identified in the report, a written corrective action plan was required. On May 30, 2019, you submitted an acceptable written corrective action plan. It is expected that the corrective action plan be implemented within the specified time frames as outlined in the approved plan. Please review the enclosed documentation for accuracy and contact me with any questions. In the event that I am not available and you need to speak to someone immediately, please contact the local office at (616) 356-0183. Sincerely, Rebecca Piccard, Licensing Consultant Bureau of Community and Health Systems Unit 13, 7th Floor, 350 Ottawa, N.W. Grand Rapids, MI 49503 (616) 446-5764 enclosure 611 W. OTTAWA P.O. BOX 30664 LANSING, MICHIGAN 48909 www.michigan.gov/lara 517-335-1980 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF LICENSING AND REGULATORY AFFAIRS BUREAU OF COMMUNITY AND HEALTH SYSTEMS SPECIAL INVESTIGATION REPORT I. IDENTIFYING INFORMATION License #: AL410302931 Investigation #: 2019A0340031 Complaint Receipt Date: 05/20/2019 Investigation Initiation Date: 05/20/2019 Report Due Date: 06/19/2019 Licensee Name: Lifehouse Crystal Manor Operations LLC Licensee Address: Suite 115 21800 Haggerty Rd., Northville, MI 48167 Licensee Telephone #: (616) 262-1792 Administrator: Jill Quick Licensee Designee: Marcia Curtiss Name of Facility: Addington Place of Grand Rapids Seaside Facility Address: 1175 68th Street S.E., Grand Rapids, MI 49508 Facility Telephone #: (616) 281-8054 Original Issuance Date: 03/25/2010 License Status: REGULAR Effective Date: 09/26/2018 Expiration Date: 09/25/2020 Capacity: 20 Program Type: PHYSICALLY HANDICAPPED MENTALLY ILL AGED 1 II. -

Topical Medications

Delegation of Medication Administering Topical Administration to Unlicensed Medication Module/Skill Checklist Assistive Personnel (UAP) Objective At the completion of this module, the UAP should be able to administer topical medications. Topical medications come in many forms – ointments, lotions, pastes, creams, powders, sprays, and shampoos. NOTE: 1) The RN or LPN is permitted to delegate ONLY after application of all components of the NCBON Decision Tree for Delegation to UAP and after careful consideration that delegation is appropriate: a) for this client, b) with this acuity level, c) with this individual UAP’s knowledge and experience, and d) now (or in the time period being planned). 2) Successful completion of the “Infection Control” module by the UAP should be documented prior to instruction in medication administration by this or ANY route. D DEFINITIONS Ointments are semi-solid preparations of drugs in an oil base. Lotions are medications dissolved in a liquid. Pastes are a mixture of powders and ointment and are often very stiff and sticky. Creams are medications in a suspension of oil and water and are easily applied to the skin. Powders are very finely ground medications that are usually sprinkled onto the affected area. Sprays are medications in a solution that can be atomized into a mist for ease of application. Shampoos are medications in a soap solution made for application to the scalp and hair. Page 1 of 3 Origin: 6/5/2014 Delegation of Medication Administering Topical Administration to Unlicensed Medication Module/Skill Checklist Assistive Personnel (UAP) Procedure 1. Perform skills in General Medication Administration Checklist. -

Using Topical Corticosteroids Safely and Effectively by Eileen Murray MD FRCPC

Using topical corticosteroids safely and effectively by Eileen Murray MD FRCPC http://thischangedmypractice.com/topical-corticosteroids/ Appendix 1 Vehicles: The vehicle makes up 95 to 99.9% of a topical medication. The main vehicles are ointments, creams, lotions, gels, and pastes. It is important to choose the correct vehicle. 1. An Ointment (water in oil emulsions) allows the best penetration of the active ingredient and is best for dry, sensitive skin, and especially for thick plaques. They are also most effective for disease on thick skin such as the palms and soles. 2. Creams (oil in water emulsions) are less greasy, spread more easily and are better tolerated. They may sting upon application and do not hydrate the skin as well as ointments 3. Lotions (oil or powder in water emulsions) are best for treating large areas. They may cause stinging and dryness. Combinations of anti-itch ingredients along with a corticosteroid in a lotion are helpful for treating widespread itching as can occur with a drug rash. 4. Gels (mixtures of water, alcohol or acetone) are best for oily or hairy skin. 5. Pastes (powder in an ointment) are very useful for wet intertriginous areas. The powder absorbs moisture and the ointment lubricates and soothes the skin. Diaper creams are a good example. Table 1: The site on the body affects percutaneous absorption Percutaneous Local factors influencing Site Best vehicle absorption absorption Palms 0.83 X Ointment thick stratum corneum Soles 0.14 X Ointment thick stratum corneum Extremities (flexural 1.0 X Ointment -

ONA Item Essential Elements for Use with ADL/IADL and Medication Management Only (Updated 6/29/2021)

ONA Item Essential Elements For use with ADL/IADL and Medication Management Only (updated 6/29/2021) This document is intended to be used as a supplement to the ONA Manual and FAQs which can be found by clicking on the following link: ONA Assessor Resource Page Instructions: Use this document along with the Coding Decision Tree and Coding Key to accurately determine which essential elements to consider for each item when coding ADL/IADL and Medication items. If the individual needs a support person’s help at least 50% of the days the activity takes place with any or all of the steps listed in the “Setup or Clean-up” column and needs no help in the “During the Activity” column, code ‘Setup/clean-up’. If the individual needs help with any or all of the steps listed in the “During the Activity” column, identify what kind of help is needed at least 50% of the days the activity takes place. Then consider the following options for coding: If the individual needs full 100 % physical assistance for all steps in the “During the Activity” column, code ‘Dependent’ regardless if help is needed in the “Setup/clean-up” column. Or, if some help is needed at least 50% of the days the activity takes place for some or all of the steps during the activity, code the kind of help that is needed: ‘Supervision’, ‘Partial/Moderate’ or ‘Substantial/Maximal’. Please note: The list below is not exhaustive. There could be elements in a person’s life that are not listed such as using conditioner in the shower, using lotion as part of a general hygiene routine or using fabric softener while doing laundry, etc.