Using Multicultural Young Adult Literature in the Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utah Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Utah Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Nickerson Family, Japanese American National Museum (97.51.3) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Utah Curriculum Writing Team RaDon Andersen Jennifer Baker David Brimhall Jade Crown Sandra Early Shanna Futral Linda Oda Dave Seiter Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum UTAH Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Topaz (Grade 4, 5, 6) Resources and References 34 Terminology and the Japanese American Experience 35 United States Confinement Sites for Japanese Americans During World War II 36 Japanese Americans in the Interior West: A Regional Perspective on the Enduring Nikkei Historical Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Utah (and Beyond) 60 State Overview Essay and Timeline 66 Selected Bibliography Appendix 78 Project Teams 79 Acknowledgments 80 Project Supporters * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). -

Super! Drama TV August 2020

Super! drama TV August 2020 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.08.01 2020.08.02 Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 5 Season 5 #10 #11 06:30 06:30 「RAPTURE」 「THE DARKNESS AND THE LIGHT」 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #19 「DANGEROUS RENDEZVOUS」 #5 「SCHISMS」 07:30 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 07:30 #19 「LONE-HANDED 90」 08:00 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN TOWARDS THE 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 FUTURE [J] GENERATION Season 6 #2 「the hibernator」 #6 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「TRUE Q」 08:30 3 #1 「'CHAOS' Part One」 09:00 09:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #15 #6 「Crab Mentality」 「KINGDOM」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 10:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 10:30 #16 2 「Survivor」 #12 11:00 11:00 「The Final Frontier」 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information [J] 11:30 information [J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 #13 #19 「A Desperate Man」 「The Good Son」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 #14 #20 「Life Before His Eyes」 「The Missionary Position」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 #15 #21 「Secrets」 「Rekindled」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 #16 #22 「Psych out」 「Playing with Fire」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 #17 #23 「Need to Know」 「Up in Smoke」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 #18 #24 「The Tell」 「Till Death Do Us Part」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 18:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 18:00 #9 Season 1 「CD-ROM + Hoagie Foil」 #19 18:30 18:30 「The Mystery of the Dodgy Draft」 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 information [J] 19:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 19:00 #14 「TWAMIE ULLULAQ (NO. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Re-Imagining United States History Through Contemporary Asian American and Latina/O Literature

LATINASIAN NATION: RE-IMAGINING UNITED STATES HISTORY THROUGH CONTEMPORARY ASIAN AMERICAN AND LATINA/O LITERATURE Susan Bramley Thananopavarn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: María DeGuzmán Jennifer Ho Minrose Gwin Laura Halperin Ruth Salvaggio © 2015 Susan Bramley Thananopavarn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Susan Thananopavarn: LatinAsian Nation: Re-imagining United States History through Contemporary Asian American and Latina/o Literature (Under the direction of Jennifer Ho and María DeGuzmán) Asian American and Latina/o populations in the United States are often considered marginal to discourses of United States history and nationhood. From laws like the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to the extensive, racially targeted immigration rhetoric of the twenty-first century, dominant discourses in the United States have legally and rhetorically defined Asian and Latina/o Americans as alien to the imagined nation. However, these groups have histories within the United States that stretch back more than four hundred years and complicate foundational narratives like the immigrant “melting pot,” the black/white binary, and American exceptionalism. This project examines how Asian American and Latina/o literary narratives can rewrite official histories and situate American history within a global context. The literary texts that I examine – including works by Carlos Bulosan, Américo Paredes, Luis Valdez, Mitsuye Yamada, Susan Choi, Achy Obejas, Karen Tei Yamashita, Cristina García, and Siu Kam Wen – create a “LatinAsian” view of the Americas that highlights and challenges suppressed aspects of United States history. -

PROFT THINGS INTERNATIONAL Pat Proft

WRONGFULLYACCUSED By Pat Proft PROFT THINGS INTERNATIONAL REVISED 4/11/97 REVISED 5/15/97 LOGO DISSOLVE TO: SUPER: 11 The following drarnatization is true, based on real events/ from other actual movies.a Building underneath the super: SOUND: A PRISON SIREN off in the distance. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. HILLSIDE - DAY CASS LAKE hears the sirens. Beautiful, cool, in control, the girl next-door with the body of a Victoria's Secret model. And an air of mystery about her. She grabs her binoculars. ANGLE - HER PAINTING ·The penitentiary with a person jumping over the wall. Cass looks through her binocs . EXT. UTILITY ROAD - PRISON TRUCK - DAY • The side of the truck reads: "A Prison Truck". In the b.g. off in the distance is the penitentiary where a break has just been discovered. In the flatbed are barrels, over stuffed, and marked "Recycled Paper", "Recycled Cans", "Recycled Plastic", and "Recycled Cycles", which is full of old bicycles. One barrel, which is marked "For Escaping", has a pair of hands holding onto the rim. The person inside starts to rock the barrel until it falls off the truck. ANGLE - BARREL Rolls down a hill. Passes a sign: "The Steepest Hill In The Whole World". POV FROM INSIDE BARREL The world spinning as we roll do,-mhill. EXT. HILLSIDE Cass is up her rollers 2 EXT. CREEK - UAY The barrel comes to a halt in the creek. Our PRISONER crawls out of the barrel, we don't see his face. Dizzy, on verJ • unsteady legs, he staggers all over, banging into tree, a bridge embankment, then bumos heads with a BEAR who is just rounding a corner, ow! Beast and man fall backward out of frame, leaves flying back up into view as they strike the ground. -

Facts on File Companion to 20Th-Century American Poetry

THE FACTS ON FILE COMPANION TO 20th-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY CD EDITED BY BURT KIMMELMAN For Diane and Jane, as always The Facts On File Companion to 20th-Century American Poetry Copyright © 2005 by Burt Kimmelman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Facts On File companion to 20th-century poetry /[edited by] Burt Kimmelman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4698-0 (alk. paper) 1. American poetry—20th century—History and criticism—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title: Companion to 20th-century poetry. II. Kimmelman, Burt. III. Facts On File, Inc. PS323.5.F33 2004 811'.509—dc22 2004050661 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design adapted by James Scotto-Lavino Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS CD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v FOREWORD vi INTRODUCTION xiv A-TO-Z ENTRIES 1 APPENDIXES I. -

Cthulhu Lives!: a Descriptive Study of the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

CTHULHU LIVES!: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY J. Michael Bestul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Prof. Bradford Clark Dr. Marilyn Motz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Outside of the boom in video game studies, the realm of gaming has barely been scratched by academics and rarely been explored in a scholarly fashion. Despite the rich vein of possibilities for study that tabletop and live-action role-playing games present, few scholars have dug deeply. The goal of this study is to start digging. Operating at the crossroads of art and entertainment, theatre and gaming, work and play, it seeks to add the live-action role-playing game, CTHULHU LIVES, to the discussion of performance studies. As an introduction, this study seeks to describe exactly what CTHULHU LIVES was and has become, and how its existence brought about the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. Simply as a gaming group which grew into a creative organization that produces artifacts in multiple mediums, the Society is worthy of scholarship. Add its humble beginnings, casual style and non-corporate affiliation, and its recent turn to self- sustainability, and the Society becomes even more interesting. In interviews with the artists behind CTHULHU LIVES, and poring through the archives of their gaming experiences, the picture develops of the journey from a small group of friends to an organization with influences and products on an international scale. -

Olentangy Local School District Literature Selection Review

Olentangy Local School District Literature Selection Review Teacher: Byard/DeGiorgio School: Hyatts Middle School Book Title: Nightjohn Genre: historical fiction Author: Gary Paulsen Pages: 112 Publisher: Laurel Leaf Copyright: 1995 In a brief rationale, please provide the following information relative to the book you would like added to the school’s book collection for classroom use. You may attach additional pages as needed. Book Summary and summary citation: (suggested resources include book flap summaries, review summaries from publisher, book vendors, etc.) Sarny, a female slave at the Waller plantation, first sees Nightjohn when he is brought there with a rope around his neck, his body covered in scars. He had escaped north to freedom, but he came back--came back to teach reading. Knowing that the penalty for reading is dismemberment Nightjohn still retumed to slavery to teach others how to read. And twelve-year-old Sarny is willing to take the risk to learn. Set in the 1850s, Gary Paulsen's groundbreaking new novel is unlike anything else the award- winning author has written. It is a meticulously researched, historically accurate, and artistically crafted portrayal of a grim time in our nation's past, brought to light through the personal history of two unforgettable characters. Provide an instructional rationale for the use of this title, including specific reference to the OLSD curriculum map(s): (Curriculum maps may be referenced by grade/course and indicator number or curriculum maps with indicators highlighted may be attached to this form) CCS #1-10 Reading Literature Include two professional reviews of this title: (a suggested list of resources for identifying professional reviews is shown below. -

Weekend Movie Schedule Pictures Fuel Fantasies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, February 24, 2006 5 sick. Your concerns about the baby are MONDAY EVENING FEBRUARY 27, 2006 justified, and you have kept this secret too 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 long. Please tell the parents-to-be so they E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Pictures fuel fantasies Flip House House flip. Confronting Evil: America Rollergirls: Searching for Crossing Jordan (TV14) Flip House House flip. can protect their little one from your 36 47 A&E (TVPG) Undercover Ann Calvello (HD) (TVPG) mother. Because you are afraid you may DEAR ABBY: I was visiting my abigail Wife Swap: Schachtner/ The Bachelor: Paris Travis chooses his mate in the KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel not be believed, start out this way: “You 4 6 ABC Martincak (N) season finale. (N) at 10 (N) (TV14) friend, “Carla,” last week and arrived a van buren may have wondered why I don’t get Animal Cops: Down and In Animal Cops - Detroit: Animal Precinct: Too Late Animal Cops: Down and In Animal Cops - Detroit: little early on our way to go shopping. 26 54 ANPL along with Mother. This is the reason — Danger (TVPG) Wounded by Wire (TV G) Danger (TVPG) Wounded by Wire While I was waiting for her to dress, I The West Wing: Internal Kathy Griffin: The D-List Outrageous Outrageous Project Runway: What’s Outrageous Outrageous and I’m worried about the safety of your 63 67 BRAVO noticed some photographs on her kitchen Displacement (HD) Celebrity culture. -

Page | 1 VON FREEMAN NEA JAZZ MASTER (2012) Interviewee: Von

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. VON FREEMAN NEA JAZZ MASTER (2012) Interviewee: Von Freeman (October 3, 1923 – August 11, 2012) Interviewer: Steve Coleman Date: May 23-24, 2000 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 110 pp. Coleman: Tuesday, May 23rd, 2000, 5:22 pm, Von Freeman oral history. My name: I’m Steve Coleman. I’ll keep this in the format that I have here. I’d like to start off with where you were born, when you were born. Freeman: Let’s see. It’s been a little problem with that age thing. Some say 1922. Some say 1923. Say 1923. Let’s make me a year younger. October the 3rd, 1923. Coleman: Why is there a problem with the age thing? Freeman: I don’t know. When I was unaware that they were writing, a lot of things said that I was born in ’22. I always thought I was born in ’23. So I asked my mother, and she said she couldn’t remember. Then at one time I had a birth certificate. It had ’22. So when I went to start traveling overseas, I put ’23 down. So it’s been wavering between ’22 and ’23. So I asked my brother Bruz. He says, “I was always two years older than you, two years your elder.” So that put me back to 1923. So I just let it stand there, for all the hysterians – historian that have written about me. -

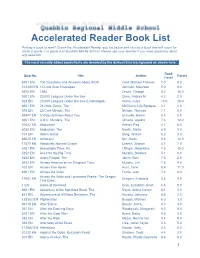

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

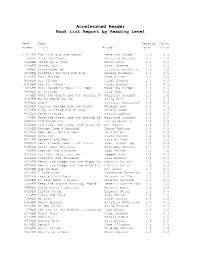

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr.