UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haraway When Species Meet.Pdf

WHEN SPECIES MEET , When Species Meet Donna J. Haraway The Poetics of DNA Judith Roof The Parasite Michel Serres WHEN SPECIES MEET Donna J. Haraway Posthumanities, Volume 3 University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London Copyright 2008 Donna J. Haraway All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haraway, Donna Jeanne. When species meet / Donna J. Haraway. p. cm. — (Posthumanities) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 978-0-8166-5045-3 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8166-5045-4 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN: 978-0-8166-5046-0 (pb : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8166-5046-2 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Human-animal relationships. I. Title. QL85.H37 2008 179´.3—dc22 2007029022 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii PART I. WE HAVE NEVER BEEN HUMAN 1. When Species Meet: Introductions 3 2. Value-Added Dogs and Lively Capital 45 3. Sharing Suffering: Instrumental Relations between Laboratory Animals and Their People 69 4. Examined Lives: Practices of Love and Knowledge in Purebred Dogland 95 5. -

Rforty Second Legislatlire Is Adourned

t 'v &iavhn.r ta& i .juV-- i ... h:-:- Xk v. HB Ijr;" 1 v i i .i-- ,j." Af,i, ? t syiHft ? f Big Spring Datlg Herald '.pS-N- O. 308 EIGHTEEN PAGES TODAY BIG SPRING, TEXAg, SUNDAy MORNING, MAY 24, 1031. MEMBER OF THE ASSOCIATED j It. rForty Second Legislat Is Adourned lire 4 i u. Chicago Hostess GrandsorfOf Girl'sMother Ruth Nichohj Society Sportswoman of the Air, " Special Tax I yrW&Sr"' ifiM5g HOME 4 Holder of Many Records, To Try for Ocean Hop Garfield Is . Leads Mob To Bills Among "...TOWN Shc Has Flown FaBlcr, il-- A LK Fatally'Sliot Missouri Jail . Higher Than Any Passed Other Woman Those k ByBgDDY Was Identified Auti- - Offers To Hang Negro Wi (Editor's Notet This Is the first iInny Measures KUI$lt Prohibition Organi-- ' With Own Hands; Man ot a series of five articles tracing wmmm w Dollworm Measure Is "Well. well. We have a nice,, To-- - zntion Attempted Attack daring Ruth Nichols' career from j ' s im y Illcommunlcatlon t hand. xou debutante to premier blrdwoman) Unsigned ,v Itpow, we never could understand i CLEVELAND, May 23 W RICHMOND, Mlnsnurl, May 23 why a person writing something to BliiiHaV I AUSTIN. May 23 UP) The forty-seco- nd " John N aarfleld, 29, grandson of (T1 A mob of 100 men waa dis- IhVpaor would not sign his or her Ily RICHARD MASSOCK -- legislature adjourned A. Garfield, died persed early tdday without vio at hamp to the article Tills one U President James NEW YORK, May 23. CP-It- ulh p. -

A Character Presentation from © Moomin Characters™

a character presentation from © Moomin Characters™ Moomin is created by the Finnish artist and author Tove Jansson in 1945, and the books have been translated into more than 40 languages. The Moomin books make up an extraordinary collection of artwork, from expressive pen and ink drawings in the novels to explosively colourful illustrations in the picture books. Thousands of comic strip illustrations complete the collection, making it a tremendous source of inspiration and material for design. A TV animation is sold to 140 countries. A new movie animation is launched in 2014. Tove Jansson 100 years - 2014. © Apple Corps Ltd, a Beatles™ product. The Beatles is the most successful phenomenon in the music history with sales of more than 1,5 billion records. The group is still selling huge, more than forty years after the break-up. There are more than 200 licensees all over the world producing many different products, and the artwork consists of thousands of photos, graphics, album covers and logotypes from the merry sixties. © 2012 King Features Syndicate, Inc/Fleischer Studios Inc. ™ Hearst Holdings, INC. /Fleischer Studios, Inc. www.bettyboop.com Betty Boop is the first sex symbol of the silver screen, created by Max Fleischer in the early thirties. She has turned out to be an American cult icon, —a forever young Diva. Her popularity is still huge, with one of the biggest licensing programs worldwide for a variety of products. The artwork is divided into many themes and emotions. In 2012 the cosmetic company Lancôme is using the Betty Boop character in a worlwide campaign. -

2014 Annual Report ...To Be Meaghan’S Social Dog

I was born to do something really important... NEADS/Dogs for Deaf and Disabled Americans 2014 Annual Report ...to be Meaghan’s Social Dog. Meaghan & Dixie: An Inseparable Team Together since 2013, Dixie is always by Meaghan’s side, and in her mother’s words,“...Dixie is the best thing that has happened to Meaghan in the last couple of years. She is the most dedicated, devoted, and sweetest animal ever. Clearly, she knows her job.” A MESSAGE FROM THE CEO Gerry DeRoche (r) reviews plans for client house with Marie Mouradian, Window Designs Etc. NEADS has been placing exceptionally about our plans for a new client house. This year, well-trained Assistance Dogs since I am happy to report that we are well on our way toward opening our new facility. !"#$. In fact, in %&!' we will place our The groundbreaking was held in June, and the th !,$&& dog to a deserving client. A lot construction crews have been hard at work ever has happened since the program was since. We are anticipating that the building will be conceived nearly (& years ago. Even completed around midyear. It is vitally important that our clients feel at home while they are on our though we have continued to add new campus, and the new client house is designed programs, at the very heart of what we with our clients in mind. Further, the new client do is to produce highly trained Assistance house will give us increased residential and training capacity. Dogs for our clients. This past year we were privileged to benefit clients There comes a time when even the best Assistance from across the country; as far away as Wyoming Dog will need to retire. -

Cthulhu Lives!: a Descriptive Study of the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

CTHULHU LIVES!: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY J. Michael Bestul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Prof. Bradford Clark Dr. Marilyn Motz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Outside of the boom in video game studies, the realm of gaming has barely been scratched by academics and rarely been explored in a scholarly fashion. Despite the rich vein of possibilities for study that tabletop and live-action role-playing games present, few scholars have dug deeply. The goal of this study is to start digging. Operating at the crossroads of art and entertainment, theatre and gaming, work and play, it seeks to add the live-action role-playing game, CTHULHU LIVES, to the discussion of performance studies. As an introduction, this study seeks to describe exactly what CTHULHU LIVES was and has become, and how its existence brought about the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. Simply as a gaming group which grew into a creative organization that produces artifacts in multiple mediums, the Society is worthy of scholarship. Add its humble beginnings, casual style and non-corporate affiliation, and its recent turn to self- sustainability, and the Society becomes even more interesting. In interviews with the artists behind CTHULHU LIVES, and poring through the archives of their gaming experiences, the picture develops of the journey from a small group of friends to an organization with influences and products on an international scale. -

Interviewing Theo and His Seeing Eye Dog Inside the Issue by Mel Weirich I Decided the Best Way to Find Changes to Lamuth…...P

LaMuth Middle School Issue 2, Spring 2015 Interviewing Theo and His Seeing Eye Dog Inside the Issue By Mel Weirich I decided the best way to find Changes to LaMuth…...p. 2 out what life is like with a seeing eye AMSCO Carnival…..... p.2 dog was to ask someone who actually has a seeing eye dog. Theo, a new Red Nose Day……...… p. 3 student at LaMuth, has a seeing eye Rosetta Mission……… p. 3 dog and let me interview him. Stop World Hunger…... p. 3 Q: What was life like before you Mr. Hoynes…………... p. 4 had a seeing eye dog to help? A: “I wasn’t as confident but now I Fine Arts Classes...……p. 5 am. People feel more open to talking Learn About Art…….…p. 5 to me because I don’t have a cane with me all the time.” Teacher Expectations.....p. 6 Q: How has having Tribord Stop Bullying……….…p. 7 (Theo’s seeing eye dog) helped with daily tasks? Year in Review………..p. 7 A: “Getting around the city has become a lot easier since he can guide Restaurant Review...…. p. 8 me around obstacles.” Q: How did you get paired up with Tribord? Brain Games Review….p. 8 A: “The trainers looked at my personality and how fast I walked, and Summer Activities…….p. 8 my orientation. They also had me walk around with several dogs. Then I walked with Tribord and he was the perfect fit for me.” Movie Review…….…...p. 9 Q: How did you get around before you had a dog to help you Book Review……….....p. -

Pioneers in Good Shape Expansion Outlined at Hanna Locker Plant

•^^JPHBRT' Pioneers In 11 tt THE HANNA HER "AND EAST CENTRAL ALBERTA NEWS? Good Shape Authorized ss Second Class Matter by th* Post Offlcs Dap rtment, Ottawa, And for th* Payment ef Poatag* In Caafc VOLUME 53 — NUMBER 15 THE HANNA HERALD AND EAST CENTRAL ALBERTA NEWS—THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 1965 FERG JAMES RE-ELECTED PRESIDENT KINSMEN RECIPIENTS OF RECOGNITION AT ANNUAL MEET'G; MEMBERSHIP NOW STANDS AT MARK OF 188 Malnutrition Ivi Bert Stock Again In Charge Of Membership and Medical Services; More Business Slated for Feb. 16 In Cattle Population The annual meeting of the Pioneer's Association of Hanna and District was held on Monday, Feb. 1 st. After the . 11 n 111 IIHI 111111 ii 11 tin 11 H in presentation of reports from various committees, the election HANNA VETERINARIAN VOICES - of Officers for 1965 took place. Ferg James was re-elected by STORK PICKS CAR acclamation, with Con. Dieter os 1st Vice-President and Sam SEAT TO "ROOST" C. Polley as 2nd Vice-President with the following Board of MUCH CONCERN OVER CONDITION OYEN, Feb. 2—Whether he Directors: Roy Embree, Mrs. Gladys Givens, Bert Stock, Harry felt the owls and eagles were Bartman ond George Anderson. getting too much attention Morgan Baldwin was also re-* — these days or not, is a question, OF STOCK EXPOSED TO SEVERE COLD elected unanimously as Secretary but one bird which oft-times Dr. E. Haworth Volunteers Ideas Treasurer of the Association for Rec. Director appears at any season of the 1965. Five prominent members of the Hanna Kinsmen Club were year and in any kind of weath On How To Keep Health of Animols Guest Speaker er, the stork "has done it The Building Committee now honored recently in recognition of outstanding service. -

The Reimagined Paradise: African Immigrants in the United States, Nollywood Film, and the Digital Remediation of 'Home'

THE REIMAGINED PARADISE: AFRICAN IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES, NOLLYWOOD FILM, AND THE DIGITAL REMEDIATION OF 'HOME' Tori O. Arthur A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2016 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Advisor Patricia Sharp Graduate Faculty Representative Vibha Bhalla Lara Lengel © 2016 Tori O. Arthur All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor This dissertation analyzes how African immigrants from nations south of the Sahara become affective citizens of a universal Africa through the consumption of Nigerian cinema, known as Nollywood, in digital spaces. Employing a phenomenological approach to examine lived experience, this study explores: 1) how American media aids African pre-migrants in constructing the United States as a paradise rooted in the American Dream; 2) immigrants’ responses when the ‘imagined paradise’ does not match their American realities; 3) the ways Nigerian films articulate a distinctly African cultural experience that enables immigrants from various nations to identify with the stories reflected on screen; and, 4) how viewing Nollywood films in social media platforms creates a digital sub-diaspora that enables a reconnection with African culture when life in the United States causes intellectual and emotional dissonance. Using voices of members from the African immigrant communities currently living in the United States and analysis of their online media consumption, this study ultimately argues that the Nigerian film industry, a transnational cinema with consumers across the African diaspora, continuously creates a fantastical affective world that offers immigrants tools to connect with their African cultural values. -

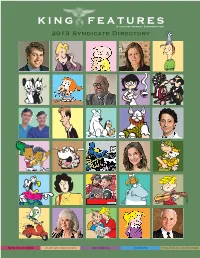

2013 Syndicate Directory

2013 Syndicate Directory NEW FEATURES CUSTOM SERVICES EDITORIAL COMICS POLITICAL CARTOONS What’s New in 2013 by Norman Feuti Meet Gil. He’s a bit of an underdog. He’s a little on the chubby side. He doesn’t have the newest toys or live in a fancy house. His parents are split up – his single mother supports them with her factory job income and his father isn’t around as often as a father ought to be. Gil is a realistic and funny look at life through the eyes of a young boy growing up under circumstances that are familiar to millions of American families. And cartoonist Norm Feuti expertly crafts Gil’s world in a way that gives us all a good chuckle. D&S From the masterminds behind Mobilewalla, the search, discovery and analytics engine for mobile apps, comes a syndicated weekly column offering readers both ratings and descriptions of highly ranked, similarly themed apps. Each week, news subscribers receive a column titled “Fastest Moving Apps of the Week,” which is the weekly hot list of the apps experiencing the most dramatic increases in popularity. Two additional “Weekly Category” features, pegged to relevant news, events, holidays and calendars, are also available. 3TW Drs. Oz and Roizen give readers quick access to practical advice on how to prevent and combat conditions that affect overall wellness and quality of life. Their robust editorial pack- age, which includes Daily Tips, a Weekly Feature and a Q & A column, covers a wide variety of topics, such as diet, exercise, weight loss, sleep and much more. -

West Islip Public Library

CHILDREN'S TITLES (including Parent Collection) - as of January 1, 2013 NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a firefighter (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a zoo (CC) G African cats (SDH) PG Agent Cody Banks 2: destination London (CC) PG Alabama moon G Aladdin (2v) (CC) G Aladdin: the Return of Jafar (CC) PG Alex Rider: Operation stormbreaker (CC) NRA Alexander Graham Bell PG Alice in wonderland (2010-Johnny Depp) (SDH) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (CC) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (SDH) (2010 release) PG Aliens in the attic (SDH) NRA All aboard America (CC) NRA All about airplanes and flying machines NRA All about big red fire engines/All about construction NRA All about dinosaurs (CC) NRA All about dinosaurs/All about horses NRA All about earthquakes (CC) NRA All about electricity (CC) NRA All about endangered & extinct animals (CC) NRA All about fish (CC) NRA All about -

Download Catalog

Fall - Winter - 2021 Don’t Wait Until It Is Too Late! We just want to issue an availability warning. When the Colonial Pipeline hack occurred the sales of Jerry Cans went beserk! We sold every single can, regardless of size, within three days! (So did every other supplier). They were supposed to last us until late Fall. Now with Hurricane Ida, and the ensuing tornados and flooding in PA, NJ, and New York, we are getting deluged with orders once again. We have a container on the water, arriving mid-October, but there’s a hitch: the cost of shipping tripled! That will have to be reflected in the prices, obviously. Furthermore, the future prices look bleak. The cost of raw materials soared 27%, and that’ll make ‘em even more pricey on the next go-around! Therefore, we encourage you to stock up NOW, before you must pay a king’s ransom for these durable NATO Jerry Cans. 5 LITER CAN GP05 $49 10 LITER CAN GP10 $58 20 LITER CAN GP20 $65 SET OF 4 20 LITER CANS GP204 $239 GET YOUR SET OF 4 20 LITER CANS GP204 $239 Before It’s Issue 113 Too LATE! Issue 113 To Order Call: 800-225-9407 or Click: www.DeutscheOptik.com Satisfaction Guaranteed oy.., what a year so far! Lo- are short-handed, and like many prices have gone up a bit due to gistics have never been so other businesses can’t find any shipping and manufacturing costs, Bfouled up, not to mention more employees. The crew is (sheet steel sky-rocketed), we are the costs involved. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ).