Dr. Alojzije Stepinac and the Jews*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grad Zagreb (01)

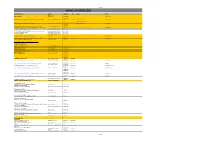

ADRESARI GRAD ZAGREB (01) NAZIV INSTITUCIJE ADRESA TELEFON FAX E-MAIL WWW Trg S. Radića 1 POGLAVARSTVO 10 000 Zagreb 01 611 1111 www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 GRADSKI URED ZA STRATEGIJSKO PLANIRANJE I RAZVOJ GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/II 01 610 1575 610-1292 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr [email protected] 01 658 5555 01 658 5609 GRADSKI URED ZA POLJOPRIVREDU I ŠUMARSTVO Zagreb, Avenija Dubrovnik 12/IV 01 658 5600 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 01 610 1169 GRADSKI URED ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE, ZAŠTITU OKOLIŠA, Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1168 IZGRADNJU GRADA, GRADITELJSTVO, KOMUNALNE POSLOVE I PROMET 01 610 1560 01 610 1173 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 1.ODJEL KOMUNALNOG REDARSTVA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 06 111 2.DEŽURNI KOMUNALNI REDAR (svaki dan i vikendom od 08,00-20,00 sati) Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 566 3. ODJEL ZA UREĐENJE GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 184 4. ODJEL ZA PROMET Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 111 Zagreb, Ulica Republike Austrije 01 610 1850 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE 18/prizemlje 01 610 1840 01 610 1881 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 485 1444 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA ZAŠTITU SPOMENIKA KULTURE I PRIRODE Zagreb, Kuševićeva 2/II 01 610 1970 01 610 1896 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA JAVNO ZDRAVSTVO Zagreb, Mirogojska 16 01 469 6111 INSPEKCIJSKE SLUŽBE-PODRUČNE JEDINICE ZAGREB: 1)GRAĐEVINSKA INSPEKCIJA 2)URBANISTIČKA INSPEKCIJA 3)VODOPRAVNA INSPEKCIJA 4)INSPEKCIJA ZAŠTITE OKOLIŠA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1111 SANITARNA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Šubićeva 38 01 658 5333 ŠUMARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Zapoljska 1 01 610 0235 RUDARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Ul Grada Vukovara 78 01 610 0223 VETERINARSKO HIGIJENSKI SERVIS Zagreb, Heinzelova 6 01 244 1363 HRVATSKE ŠUME UPRAVA ŠUMA ZAGREB Zagreb, Kosirnikova 37b 01 376 8548 01 6503 111 01 6503 154 01 6503 152 01 6503 153 01 ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING d.o.o. -

Belgrade - Budapest - Ljubljana - Zagreb Sample Prospect

NOVI SAD BEOGRAD Železnička 23a Kraljice Natalije 78 PRODAJA: PRODAJA: 021/422-324, 021/422-325 (fax) 011/3616-046 [email protected] [email protected] KOMERCIJALA: KOMERCIJALA 021/661-07-07 011/3616-047 [email protected] [email protected] FINANSIJE: [email protected] LICENCA: OTP 293/2010 od 17.02.2010. www.grandtours.rs BELGRADE - BUDAPEST - LJUBLJANA - ZAGREB SAMPLE PROSPECT 1st day – BELGRADE The group is landing in Serbia after which they get on the bus and head to the downtown Belgrade. Sightseeing of the Belgrade: National Theatre, House of National Assembly, Patriarchy of Serbian Orthodox Church etc. Upon request of the group, Tour of The Saint Sava Temple could be organized. The tour of Kalemegdan fortress, one of the biggest fortress that sits on the confluence of Danube and Sava rivers. Upon request of the group, Avala Tower visit could be organized, which offers a view of mountainous Serbia on one side and plain Serbia on the other. Departure for the hotel. Dinner. Overnight stay. 2nd day - BELGRADE - NOVI SAD – BELGRADE Breakfast. After the breakfast the group would travel to Novi Sad, consider by many as one of the most beautiful cities in Serbia. Touring the downtown's main streets (Zmaj Jovina & Danube street), Danube park, Petrovaradin Fortress. The trip would continue towards Sremski Karlovci, a beautiful historic place close to the city of Novi Sad. Great lunch/dinner option in Sremski Karlovci right next to the Danube river. After the dinner, the group would head back to the hotel in Belgrade. -

Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Monday, August

Saint John Gualbert Cathedral PO Box 807 Johnstown PA 15907-0807 539-2611 Stay awake and be ready! 536-0117 For you do not know on what day your Lord will come. Cemetery Office 536-0117 Fax 535-6771 Sunday, August 11, - Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Readings: Wisdom 18:6-9/ Hebrews 11:1-2, 8-19 or 11:1-2, 8-12/ Luke 12:32-48 or 12:35-40 [email protected] 8:00 am: For the Intentions of the People of the Parish 11:00 am: Clarence Michael O’Shea (Great Granddaughter Dianne O’Shea) Bishop 5:00 pm: John Concannon (Kevin Klug) Most Rev Mark L Bartchak, DD Monday, August 12, - Weekday, Saint Jane Frances de Chantal, Religious Rector & Pastor Readings: Deuteronomy 10:12-22/ Matthew 17:22-27 Very Rev James F Crookston 7:00 am: Saint Anne Society 12:05 pm: Sophie Wegrzyn, Birthday Remembrance (Son, John) Parochial Vicar Father Clarence S Bridges Tuesday, August 13, - Weekday, Saints Pontian, Pope, & Hippolytus, Priest, Martyrs Readings: Deuteronomy 31:1-8/ Matthew 18:1-5, 10, 12-14 In Residence 7:00 am: Living & Deceased Members of 1st Catholic Slovac Ladies Father Sean K Code 12:05 pm: Bishop Joseph Adamec (Deacon John Concannon, Monica & Angela Kendera) SUNDAY LITURGY Wednesday, Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Priest & Martyr Saturday Evening Readings: Deuteronomy 34:1-12/ Matthew 18:15-20 5:00 pm Vigil Readings: 1 Chronicles 15:3-4, 15-16; 16:1-2/ 1 Corinthians 15:54b-57/ Luke 11:27-28 Sundays 7:00 am: Carole Vogel (Helen Muha) 8:00 am 12:05 pm: Anna Mae Cicon (Daughter, Melanie) 11:00 am 6:00 pm: Sara (Connors) O’Shea (Great Granddaughter, Dianne O’Shea 5:00 pm Thursday, August 15, - The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Readings: Revelation 11:19a; 12:1-6a, 10ab/ Corinthians 15:20-27/ Luke 1:39-50 7:00 am: Robert F. -

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Angels Bible

ANGELS All About the Angels by Fr. Paul O’Sullivan, O.P. (E.D.M.) Angels and Devils by Joan Carroll Cruz Beyond Space, A Book About the Angels by Fr. Pascal P. Parente Opus Sanctorum Angelorum by Fr. Robert J. Fox St. Michael and the Angels by TAN books The Angels translated by Rev. Bede Dahmus What You Should Know About Angels by Charlene Altemose, MSC BIBLE A Catholic Guide to the Bible by Fr. Oscar Lukefahr A Catechism for Adults by William J. Cogan A Treasury of Bible Pictures edited by Masom & Alexander A New Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture edited by Fuller, Johnston & Kearns American Catholic Biblical Scholarship by Gerald P. Fogorty, S.J. Background to the Bible by Richard T.A. Murphy Bible Dictionary by James P. Boyd Christ in the Psalms by Patrick Henry Reardon Collegeville Bible Commentary Exodus by John F. Craghan Leviticus by Wayne A. Turner Numbers by Helen Kenik Mainelli Deuteronomy by Leslie J. Hoppe, OFM Joshua, Judges by John A. Grindel, CM First Samuel, Second Samuel by Paula T. Bowes First Kings, Second Kings by Alice L. Laffey, RSM First Chronicles, Second Chronicles by Alice L. Laffey, RSM Ezra, Nehemiah by Rita J. Burns First Maccabees, Second Maccabees by Alphonsel P. Spilley, CPPS Holy Bible, St. Joseph Textbook Edition Isaiah by John J. Collins Introduction to Wisdom, Literature, Proverbs by Laurance E. Bradle Job by Michael D. Guinan, OFM Psalms 1-72 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Psalms 73-150 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther by James A. -

On the Concealment of Ante Pavelić in Austria in 1945-1946

UDK: 314.743(436)-05 Pavelić, A.''1945/1946'' Izvorni znanstveni članak Received: September 5, 2011 Accepted: November 7, 2011 ON THE CONCEALMENT OF ANTE PAVELIĆ IN AUSTRIA IN 1945-1946 Ante DELIĆ* Based on available American and British documents and thus-far unconsulted papers left behind by Ante Pavelić, the leader of the Independent State of Croatia, the author analyzes Pavelić’s concealment in Austria and the role of Western agencies therein. Some of the relevant literature indicates that the Catholic Church and Western agencies took part in Pavelić’s concealment. The author concludes that all such conjecture lacks any foundation in the available sources. Key words: Ante Pavelić, Western allies, extradition, Yugoslavia Historiography is generally familiar with the fate of the army of the Inde- pendent State of Croatia and the civilian population which, at the end of the war in early May 1945, withdrew toward Austria in fear of advancing commu- nist forces, with the aim of surrendering to the Allies. These people were ex- tradited to the Yugoslav army with the explanation that they would be treated in compliance with the international laws of war. As it transpired, this “treat- ment” was one of the most tragic episodes in the history of the Croatian nation, known under the terms Bleiburg and the Way of the Cross.1 A portion of these refugees who managed to elude this fate ended up in Allied refugee camps, mostly in Italy, Austria and Germany.2 However, even in these camps, besides * Ante Delić, MA, University of Zadar, Zadar, Republic of Croatia 1 Cf. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS May 8, 1980 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

10672 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS May 8, 1980 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS NATIONAL SECURITY LEAKS potentiaf sources of intelligence infor Some of the stories say this informa mation abroad are reluctant to deal tion is coming out after all of the with our intelligence services for fear people involved have fled to safety. HON. LES ASPIN that their ties Will be exposed on the Maybe and maybe not. But if we are OF WISCONSIN front pages of American newspapers, worried about the cooperatic1n of for IN THE -HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES either because of leaks from Congress eigners, leaks like these would make Thursday, May 8, ,1980 or because sensitive material has been them extremely nervous about cooper leveraged out of the administration by ation. How can the leaker or leakers e Mr. ASPIN. Mr. Speaker, it is time FOIA. know everyone is safe? that we in Congress complain -}ust as We are also being told that, because Mr. Speaker, if foreigners are reluc loudly as those in the administration foreigners are fearful that secrets will tant to cooperate with us, it is the about national security leaks. be leaked, the intelligence agencies fault of our own agencies. Administrations, be they Republican must have the power to blue pencil They should know that the fault is or Democrat, have a predilection for manuscripts written by present and not. in Congress or in the FOIA but in pointing at Congress and bewailing former intelligence officers to make themselves. Recall that despite weeks the fact that the legislative branch sure they don't reveal anything sensi of forewarning, our people rushed out can't keep a secret. -

Photography, Collaboration and the Holocaust: Looking at the Independent State of Croatia (1941– 1945) Through the Frame of the ‘Hooded Man’

JPR Photography, Collaboration and the Holocaust: Looking at the Independent State of Croatia (1941– 1945) through the Frame of the ‘Hooded Man’ Lovro Kralj rom the 1904 photograph of a father staring at the severed hand and foot of his daughter in the Congo, to the 2004 Abu Ghraib photo of the ‘Hooded Man’, visual representations of mass vi- olence and genocide in the past century have been dominated Fby atrocity images depicting dehumanization, humiliation, torture and executions. Reflecting on the significance of the Abu Ghraib photo- graphs, Susan Sontag has noted that ‘photographs have laid down the track of how important conflicts are judged and remembered’.1 In other words, images have the power to significantly shape our interpretation and memory of historical events. Despite the large circulation of atrocity photographs depicting gen- ocide and the Holocaust in World War II Croatia,2 it was not the im- age of victims that became the predominant visual representation of Ustasha terror but that of the perpetrators of this terror. As a response to Cortis and Sonderegger’s re-take of the Abu Ghraib picture, this pa- per will discuss a picture taken by taken by Heinrich Hoffman, Hitler’s personal photographer, on 6 June 1941. The picture in question depicts the first meeting between Ante Pavelić, the leader of the Croatian fas- cist Ustasha movement, and Hitler.3 The photograph, taken at Berghof, shows Hitler in a physically superior position, standing two steps above Pavelić: the Führer bending down to shake his hand. The exchange is observed by a German sentinel in the back and SS officers to his side, isolating Pavelić as the sole figure from the Ustasha delegation. -

Usporedba Topličkog Turizma U Hrvatskoj I Sloveniji Na Primjeru "Termi Tuhelj" I "Termi Olimia"

Usporedba topličkog turizma u Hrvatskoj i Sloveniji na primjeru "Termi Tuhelj" i "Termi Olimia" Matejak, Mislav Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:217:784986 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of Faculty of Science - University of Zagreb Mislav Matejak Usporedba topličkog turizma u Hrvatskoj i Sloveniji na primjeru „Termi Tuhelj“ i „Termi Olimia“ Diplomski rad Zagreb 2019. Mislav Matejak Usporedba topličkog turizma u Hrvatskoj i Sloveniji na primjeru „Termi Tuhelj“ i „Termi Olimia“ Diplomski rad predan na ocjenu Geografskom odsjeku Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu radi stjecanja akademskog zvanja magistra geografije Zagreb 2019. Ovaj je diplomski rad izrađen u sklopu diplomskog sveučilišnog studija Geografija; smjer: Baština i turizam na Geografskom odsjeku Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, pod vodstvom izv. prof. dr. sc. Vuka Tvrtka Opačića II TEMELJNA DOKUMENTACIJSKA KARTICA Sveučilište u Zagrebu Diplomski rad Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Geografski odsjek Usporedba topličkog turizma u Hrvatskoj i Sloveniji na primjeru „Termi Tuhelj“ i „Termi Olimia“ Mislav Matejak Izvadak: Toplički turizam je glavna vrsta turizma i u hrvatskoj općini Tuhelj i u slovenskoj općini Podčetrtek u kojima se nalaze termalni kompleksi „Terme Tuhelj“ i „Terme Olimia“. „Terme Tuhelj“ i „Terme Olima“ su povezane činjenicom da se nalaze u blizini jedne drugih, a dijele i vlasničku strukturu. Točnije, „Terme Tuhelj“ su u vlasništvu „Termi Olimia“. Zbog geografske blizine i zajedničke vlasničke strukture, njihova pozicija na tržištu i razvojne mogućnosti su jedinstveni. -

The Croats Under the Rulers of the Croatian National Dynasty

THE CROATS Fourteen Centuries of Perseverance Publisher Croatian World Congress (CWC) Editor: Šimun Šito Ćorić Text and Selection of Illustrations Anđelko Mijatović Ivan Bekavac Cover Illustration The History of the Croats, sculpture by Ivan Meštrović Copyright Croatian World Congress (CWC), 2018 Print ITG d.o.o. Zagreb Zagreb, 2018 This book has been published with the support of the Croatian Ministry of culture Cataloguing-in-Publication data available in the Online Catalogue of the National and University Library in Zagreb under CIP record 001012762 ISBN 978-953-48326-2-2 (print) 1 The Croats under the Rulers of the Croatian National Dynasty The Croats are one of the oldest European peoples. They arrived in an organized manner to the eastern Adriatic coast and the re- gion bordered by the Drina, Drava and Danube rivers in the first half of the seventh century, during the time of major Avar-Byzan- tine Wars and general upheavals in Europe. In the territory where they settled, they organized During the reign of Prince themselves into three political entities, based on the previ Branimir, Pope John VIII, ous Roman administrative organizations: White (western) the universal authority at Croatia, commonly referred to as Dalmatian Croatia, and Red the time, granted (southern) Croatia, both of which were under Byzantine su Croatia international premacy, and Pannonian Croatia, which was under Avar su recognition. premacy. The Croats in Pannonian Croatia became Frankish vassals at the end of the eighth century, while those in Dalmatia came under Frankish rule at the beginning of the ninth century, and those in Red Croatia remained under Byzantine supremacy. -

The Croatian Ustasha Regime and Its Policies Towards

THE IDEOLOGY OF NATION AND RACE: THE CROATIAN USTASHA REGIME AND ITS POLICIES TOWARD MINORITIES IN THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF CROATIA, 1941-1945. NEVENKO BARTULIN A thesis submitted in fulfilment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales November 2006 1 2 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Nicholas Doumanis, lecturer in the School of History at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia, for the valuable guidance, advice and suggestions that he has provided me in the course of the writing of this thesis. Thanks also go to his colleague, and my co-supervisor, Günther Minnerup, as well as to Dr. Milan Vojkovi, who also read this thesis. I further owe a great deal of gratitude to the rest of the academic and administrative staff of the School of History at UNSW, and especially to my fellow research students, in particular, Matthew Fitzpatrick, Susie Protschky and Sally Cove, for all their help, support and companionship. Thanks are also due to the staff of the Department of History at the University of Zagreb (Sveuilište u Zagrebu), particularly prof. dr. sc. Ivo Goldstein, and to the staff of the Croatian State Archive (Hrvatski državni arhiv) and the National and University Library (Nacionalna i sveuilišna knjižnica) in Zagreb, for the assistance they provided me during my research trip to Croatia in 2004. I must also thank the University of Zagreb’s Office for International Relations (Ured za meunarodnu suradnju) for the accommodation made available to me during my research trip. -

St. Ignatius of Loyola and Sāntideva As Companions on the Way of Life Tomislav Spiranec

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations Student Scholarship 4-2018 Virtues/Pāramitās: St. Ignatius Of Loyola and Sāntideva as Companions on the Way of Life Tomislav Spiranec Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Spiranec, Tomislav, "Virtues/Pāramitās: St. Ignatius Of Loyola and Sāntideva as Companions on the Way of Life" (2018). Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations. 17. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations/17 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIRTUES/PARA.MIT .AS: ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA AND SANTIDEVA AS COMPANIONS ON THE WAY OF LIFE A dissertation by Tomislav Spiranec, S.J. presented to The Faculty of the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sacred Theology Berkeley, California April, 2018 Committee ------===~~~~~~~j_ 't /l!;//F Dr. Eduardo Fernandez, S.J., S.T. 4=:~ .7 Alexander, Ph.D., Reader lf/ !~/lg Ph.D., Reader y/lJ/li ------------',----\->,----"'~----'- Abstract VIRTUES/PARAMIT AS: ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA AND SANTIDEVA AS COMPANIONS ON THE WAY OF LIFE Tomislav Spiranec, S.J. This dissertation conducts a comparative study of the cultivation of the virtues in Catholic spiritual tradition and the perfections (paramitas) in the Mahayana Buddhist traditions in view of the spiritual needs of contemporary Croatian young adults.