Reintroducing the City in Havana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

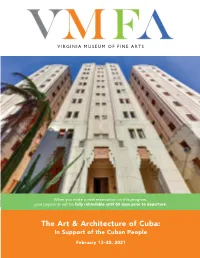

The Art & Architecture of Cuba

VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS When you make a new reservation on this program, your payments will be fully refundable until 60 days prior to departure. The Art & Architecture of Cuba: In Support of the Cuban People February 13–20, 2021 HIGHLIGHTS ENGAGE with Cuba’s leading creators in exclusive gatherings, with intimate discussions at the homes and studios of artists, a private rehearsal at a famous dance company, and a phenomenal evening of art and music at Havana’s Fábrica de Arte Cubano DELIGHT in a private, curator-led tour at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Havana, with its impressive collection of Cuban artworks and international masterpieces from Caravaggio, Goya, Rubens, and other legendary artists CELEBRATE and mingle with fellow travelers at exclusive receptions, including a cocktail reception with a sumptuous dinner in the company of the President of The Ludwig Foundation of Cuba and an after-tours tour and reception at the dazzling Ceramics Museum MEET the thought leaders who are shaping Cuban society, including the former Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, who will share profound insights on Cuban politics DISCOVER the splendidly renovated Gran Teatro de La Habana Alicia Alonso, the ornately designed, Neo-Baroque- style home to the Cuban National Ballet Company, on a private tour ENJOY behind-the-scenes tours and meetings with workers at privately owned companies, including a local workshop for Havana’s classic vehicles and a factory producing Cuban cigars VENTURE to the picturesque Cuban countryside for When you make a new reservation on this program, a behind-the-scenes tour of a beautiful tobacco plantation your payments will be fully refundable until 60 days prior to departure. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Identification and Remediation of Water-Quality Hotspots in Havana

J.J. Iudicello et al.: Identification and Remediation of Water-Quality Hotspots in Havana, Cuba 72 ISSN 0511-5728 The West Indian Journal of Engineering Vol.35, No.2, January 2013, pp.72-82 Identification and Remediation of Water-Quality Hotspots in Havana, Cuba: Accounting for Limited Data and High Uncertainty Jeffrey J. Iudicelloa Ψ, Dylan A. Battermanb, Matthew M. Pollardc, Cameron Q. Scheidd, e and David A. Chin Department of Civil, Architectural, and Environmental Engineering, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA a E-mail: [email protected] b E-mail: [email protected] c E-mail: [email protected] d E-mail: [email protected] e E-mail: [email protected] Ψ Corresponding Author (Received 19 May 2012; Revised 26 November 2012; Accepted 01 January 2013) Abstract: A team at the University of Miami (UM) developed a water-quality model to link in-stream concentrations with land uses in the Almendares River watershed, Cuba. Since necessary data in Cuba is rare or nonexistent, water- quality standards, pollutant data, and stormwater management data from the state of Florida were used, an approach justified by the highly correlated meteorological patterns between South Florida and Havana. A GIS platform was used to delineate the watershed and sub-watersheds and breakdown the watershed into urban and non-urban land uses. The UM model provides a relative assessment of which river junctions were most likely to exceed water-quality standards, and can model water-quality improvements upon application of appropriate remediation strategies. The pollutants considered were TN, TP, BOD5, fecal coliform, Pb, Cu, Zn, and Cd. -

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1 Louisiana Historical Background 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 •Spain sides with France in the now expanded Seven Years War •The Treaty of Fontainebleau was a secret agreement of 1762 in which France ceded Louisiana (New France) to Spain. •Spain acquires Louisiana Territory from France 1763 •No troops or officials for several years •The colonists in western Louisiana did not accept the transition, and expelled the first Spanish governor in the Rebellion of 1768. Alejandro O'Reilly suppressed the rebellion and formally raised the Spanish flag in 1769. Antonio de Ulloa Alejandro O'Reilly 1763 – 1770 1763 – 1770 •France’s secret treaty contained provisions to acquire the western Louisiana from Spain in the future. •Spain didn’t really have much interest since there wasn’t any precious metal compared to the rest of the South America and Louisiana was a financial burden to the French for so long. •British obtains all of Florida, including areas north of Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Maurepas and Bayou Manchac. •British built star-shaped sixgun fort, built in 1764, to guard the northern side of Bayou Manchac. •Bayou Manchac was an alternate route to Baton Rouge from the Gulf bypassing French controlled New Orleans. •After Britain acquired eastern Louisiana, by 1770, Spain became weary of the British encroaching upon it’s new territory west of the Mississippi. •Spain needed a way to populate it’s new territory and defend it. •Since Spain was allied with France, and because of the Treaty of Allegiance in 1778, Spain found itself allied with the Americans during their independence. -

Racism in Cuba Ronald Jones

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound International Immersion Program Papers Student Papers 2015 A Revolution Deferred: Racism in Cuba Ronald Jones Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ international_immersion_program_papers Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ronald Jones, "A Revolution Deferred: Racism in Cuba," Law School International Immersion Program Papers, No. 9 (2015). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Immersion Program Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopaA Revolution Deferred sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfRacism in Cuba 4/25/2015 ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj Ron Jones klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe rtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjk Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Slavery in Cuba ....................................................................................................................................... -

A Family Program in Cuba December 27, 2019 - January 1 , 2020

NEW YEAR’S IN HAVANA: A FAMILY PROGRAM IN CUBA DECEMBER 27, 2019 - JANUARY 1 , 2020 As diplomatic and economic ties between the United States and Cuba are reformed over the next few years, the landscape of Cuba will dramatically change, making it more important than ever to experience Cuba as it is today. On this family-friendly program to Havana, experience a variety of Cuban art, music, and dance with activities aimed at all ages. Enjoy playing a baseball game with Cubans close to Hemingway’s favorite hang-out in Cojimar. Dine at some of the most popular paladares, private restaurants run by Cuban entrepreneurs—often in family homes. Learn about the nation’s history and economic structure, and discuss the reforms driving changes with your Harvard study leader and local guest speakers. Learn how to salsa in a private class—and much more! The Harvard Alumni Association is operating this educational program under the General License authorized by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). This program differs from more traditional trips in that every hour must be accounted for. Each day has been structured to provide meaningful interactions with Cuban people or educational or cultural programming. Please note that Harvard University intends to fully comply with all requirements of the General License. Travelers must participate in all group activities. GROUP SIZE: Up to 30 guests PRICING: To be announced STUDY LEADER: To be announced Enjoy lunch at La Moneda Cubana, a roof-top SCHEDULE BY DAY paladar in the heart of Old Havana. B=Breakfast, L=Lunch, D=Dinner After lunch, stop at Los Clandestina, which was founded by young Cuban artists and entrepreneurs, Clandestina is Cuba’s first FRIDAY, DECEMBER 27 design store—providing both tourists and MIAMI / HAVANA residents with contemporary products that are uniquely designed and manufactured in Independent arrivals in Havana. -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

Architecture and Preservation in Havana, Cuba a Trip Sponsored Utah Heritage Foundation April 3-9, 2016

Architecture and Preservation in Havana, Cuba A Trip Sponsored Utah Heritage Foundation April 3-9, 2016 Utah Heritage Foundation is pleased to announce its first program in celebration of the organization’s 50th Anniversary in 2016 – Architecture and Preservation in Havana, Cuba. Cuba has often been referred to as a land lost in time. 1957 Chevys still cruise the streets and Havana neighborhoods display building representing over five centuries of rich heritage. The salt, humidity, and hurricanes have no doubt taken their toll on these architectural masterpieces, but time has made it more evident that the buildings are in need of serious repair. The Cuban government has been working diligently to rehabilitate these buildings, but it’s a massive undertaking that’s been made even more difficult due to the U.S. embargo. Historic preservation has become a key strategy and innovative tool for the revitalization and sustainable economic development of distressed urban neighborhoods of Havana and rural areas in Cuba. These examples provide models for the revitalization and sustainable development of urban and rural areas in other economically challenged areas of the world, including the United States. Friday, August 14, 2015 marked the grand reopening ceremony for the U.S. embassy in Havana. Progress in normalizing relations with Cuba is quickly being made and changes to the landscape are inevitable. Although only ninety miles of ocean separate us from Havana, it sometimes feels like we are worlds apart. However, we can find commonality with the Cuban people through our desire to preserve our architectural legacy. What will the progress between Washington, D.C. -

Havana XIII Biennial Tour 2 - Vip Art Tour 7 Days/ 6 Nights

Havana XIII Biennial Tour 2 - Vip Art Tour 7 Days/ 6 Nights Tour Dates: Friday, April 12th to Thursday, April 19th Friday, April 19th to Thursday, April 25th Group Size: Limit 10 people Itinerary Day 1 – Friday - Depart at 9:20 am from Miami International Airport in Delta Airline flight DL 650, arriving in Havana at 10:20 am. After clearing immigrations and customs, you will be greeted at the airport and driven to your Hotel. Check-in and relax and get ready for the adventure of a life time. Experience your first glimpse of the magic of Cuba when a fleet of Classic Convertibles American Cars picks up the group before sundown for an unforgettable tour of Havana along the Malecón, Havana’s iconic seawall, that during the Biennale turns into an interactive art gallery. The tour will end across the street of The Hotel Nacional at Restaurant Monseigneur, for Welcome Cocktails and Dinner. You will be able to interact with Cuban artists and musicians that will be invited to join the group and engage in friendly discussion about Cuban culture and art all the time listening to live Cuban music from yesterday. (D) Day 2 – Saturday - Walking tour of the Old City. Old Havana is truly a privileged place for art during the Biennale. During our walking tour we will wander through the four squares, Plaza de Armas, Plaza de San Francisco, Plaza Vieja, and Plaza de la Catedral de San Cristóbal de La Habana, and view the vast array of art exhibits and performance art that will be taking place at the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center, and other stablished venues, such as El Taller Experimental de Gráfica, the Center for the Development of Visuals Arts, and La Fototeca. -

Cuba Myths and Facts

Myths And Facts About The U.S. Embargo On Medicine And Medical Supplies A report prepared by Oxfam America and the Washington Office on Latin America BASIC FACTS: The Cuban health care system functioned effectively up through the 1980s. Life expectancy increased, infant mortality declined, and access to medical care expanded. Cuba began to resemble the developed nations in health care figures. While the U.S. embargo prevented Cuba from buying medicines and medical supplies directly from the United States, many U.S. products were available from foreign subsidiaries. Cuba may have paid higher prices, and heavier shipping costs, but it was able to do so. The Cuban health care system has been weakened in the last seven years, as the end of Soviet bloc aid and preferential trade terms damaged the economy overall. The economy contracted some 40%, and there was simply less money to spend on a health care system, or on anything else. And because the weakened Cuban economy generated less income from foreign exports, there was less hard currency available to import foreign goods. This made it more difficult to purchase those medicines and medical equipment that had traditionally come from abroad, and contributed to shortages in the Cuban health care system. In the context of the weakened Cuban economy, the U.S. embargo exacerbated the problems in the health care system. The embargo forced Cuba to use more of its now much more limited resources on medical imports, both because equipment and drugs from foreign subsidiaries of U.S. firms or from non-U.S. -

8 Day Cuba Program for Stetson - January 3-10, 2015

8 DAY CUBA PROGRAM FOR STETSON - JANUARY 3-10, 2015 - Participants should know that Cuba is a special destination, and so please understand that all elements of this itinerary are subject to change and that times and activities listed below are approximate. Please remain flexible as there are often circumstances beyond our control and changes may be necessary. The tour leader reserves the right to make changes to the published itinerary whenever, in his sole discretion, conditions warrant, or if he deems it necessary for the comfort or safety of the program. Be assured that all efforts will be made to provide a comparable alternative should an item on the itinerary need to be changed or cancelled. Program includes: ● Airfare to Havana (HAV), Cuba, either from Tampa (TPA) or Miami (MIA). ● Medical insurance while in Cuba. ● 7 nights hotel accommodations at the Inglaterra Hotel, well located, Old Havana. ● Breakfast daily (B), 4 lunches (L) and 2 dinners (D). ● English-speaking guide and private bus transfers for certain program activities. ● Daily people-to-people exchanges with local Cubans. ● Day trip to the UNESCO World Heritage site of the Viñales Valley in the west. ● All items mentioned in tour below. (subject to change) Items mentioned below in ALL CAPS are included in your program fee HOTEL INGLATERRA in Old Havana-Hotel Inglaterra, of 4 stars category, is one of the most classic hotels in Havana. Hotel Inglaterra, considered the doyen of the tourist establishments of the island of Cuba, is located on Paseo del Prado Ave. #416 between San Rafael and San Miguel Streets, Old Havana, City of Havana, Cuba.