Bass Guitar for Dummies, 2Nd Edition Is an Easy-To-Follow • Exercises to Improve Your Bass Guitar Reference That Gets You Playing Quickly! Technique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music

1 Kristen Masada and Razvan Bunescu: A Segmental CRF Model for Chord Recognition in Symbolic Music A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music minished triads most frequently contain a diminished A chord is a group of notes that form a cohesive har- seventh interval (9 half steps), producing a fully di- monic unit to the listener when sounding simulta- minished seventh chord, or a minor seventh interval, neously (Aldwell et al., 2011). We design our sys- creating a half-diminished seventh chord. tem to handle the following types of chords: triads, augmented 6th chords, suspended chords, and power A.2 Augmented 6th Chords chords. An augmented 6th chord is a type of chromatic chord defined by an augmented sixth interval between the A.1 Triads lowest and highest notes of the chord (Aldwell et al., A triad is the prototypical instance of a chord. It is 2011). The three most common types of augmented based on a root note, which forms the lowest note of a 6th chords are Italian, German, and French sixth chord in standard position. A third and a fifth are then chords, as shown in Figure 8 in the key of A minor. built on top of this root to create a three-note chord. In- In a minor scale, Italian sixth chords can be seen as verted triads also exist, where the third or fifth instead iv chords with a sharpened root, in the first inversion. appears as the lowest note. The chord labels used in Thus, they can be created by stacking the sixth, first, our system do not distinguish among inversions of the and sharpened fourth scale degrees. -

Year 11 Music Revision Guide

Year 11 Music Revision Guidance Name the musical instrument In the exam you will be asked to name different instruments that you can hear playing. If you do not play one of these instruments it can sometimes be quite difficult to pick out what each one sounds like. You will need to know what the different instruments of the orchestra sound like, what popular musical instruments sound like and what some world instruments sound like (sitar). It is worth you visiting www.dsokids.com or www.compositionlab.co.uk where you will be able to hear these instruments individually. Describing musical sounds For some questions in the exam you will need to describe what is happening in the music, in detail! If you are asked to comment on what is happening in the music you may need to describe what a particular instrument is doing, for example: ‘The left hand of the piano is playing ascending arpeggios’. The more detail you can provide, the better! Melodic movement You may be asked to describe what is happening in the melody of a song. Remember, this means the main tune. In popular music this is often the vocal line or in instrumental music it can be described as the instrument that has the main tune (the bit that you could whistle). It could move by STEP; this means it moves to the note next to it. It could move by LEAP; this means that the melody jumps from one note to another but misses some notes out in between. This could be a low note jumping to a high note or vice versa. -

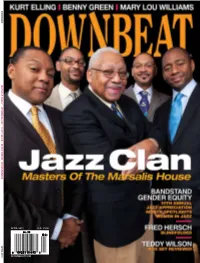

Downbeat.Com April 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. PRIL 2011 DOWNBEAT.COM A D OW N B E AT MARSALIS FAMILY // WOMEN IN JAZZ // KURT ELLING // BENNY GREEN // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2011 APRIL 2011 VOLume 78 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Maureen Flaherty ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, -

Figured-Bass.Pdf

Basic Theory Quick Reference: Figured Bass Figured bass was developed in the Baroque period as a practical short hand to help continuo players harmonise a bass line at sight. The basic principle is very easy: each number simply denotes an interval above the bass note The only complication is that not every note of every chord needed is given a figure. Instead a convention developed of writing the minimum number of figures needed to work out the harmony for each bass note. The continuo player presumes that the bass note is the root of the chord unless the figures indicate otherwise. The example below shows the figuring for common chords - figures that are usually omitted are shown in brackets: Accidentals Where needed, these are placed after the relevant number. Figures are treated exactly the same as notes on the stave. In the example below the F# does not need an accidental, because it is in the key signature. On the other hand, the C# does to be shown because it is not in the key signature. An accidental on its own always refers to the third above the bass note. 33 For analytical purposes we will combine Roman Numerals (i.e. I or V) with figured bass to show the inversion. Cadential 6/4 Second inversion chords are unstable and in the Western Classical Tradition they tend to resolve rather than stand as a proper chord on their own. In the example below, the 6/4 above the G could be described as a C chord in second inversion. In reality, though, it resolves onto the G chord that follows and can better be understood as a decoration (double appoggiatura) onto this chord. -

Figured-Bass Notation

MU 182: Theory II R. Vigil FIGURED-BASS NOTATION General In common-practice tonal music, chords are generally understood in two different ways. On the one hand, they can be seen as triadic structures emanating from a generative root . In this system, a root-position triad is understood as the "ideal" or "original" form, and other forms are understood as inversions , where the root has been placed above one of the other chord tones. This approach emphasizes the structural similarity of chords that share a common root (a first- inversion C major triad and a root-position C major triad are both C major triads). This type of thinking is represented analytically in the practice of applying Roman numerals to various chords within a given key - all chords with allegiance to the same Roman numeral are understood to be related, regardless of inversion and voicing, texture, etc. On the other hand, chords can be understood as vertical arrangements of tones above a given bass . This system is not based on a judgment as to the primacy of any particular chordal arrangement over another. Rather, it is simply a descriptive mechanism, for identifying what notes are present in addition to the bass. In this regime, chords are described in terms of the simplest possible arrangement of those notes as intervals above the bass. The intervals are represented as Arabic numerals (figures), and the resulting nomenclatural system is known as figured bass . Terminological Distinctions Between Roman Numeral Versus Figured Bass Approaches When dealing with Roman numerals, everything is understood in relation to the root; therefore, the components of a triad are the root, the third, and the fifth. -

Teaching Tuba Students to Be Complete Musicians Brandon E

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Fall 2017 Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians Brandon E. Cummings [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Educational Methods Commons, Music Education Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Brandon E., "Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians" (2017). Honors Research Projects. 577. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/577 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Running head: TEACHING TUBA STUDENTS TO BE COMPLETE MUSICIANS 1 Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians Brandon E. Cummings The University of Akron TEACHING TUBA STUDENTS TO BE COMPLETE MUSICIANS 2 Abstract The goal of music educators is to develop complete musicians who successfully learn and perform all musical concepts. One of the limitations of the band classroom is that performers are required to play a part that is specifically written with the needs of the ensemble in mind, and not the needs of the developing musician. -

Tres Bajistas De Leyenda

TRES BAJISTAS DE LEYENDA —THE THUNDER TOUR“ 29 DE OCTUBRE: Sala Razzmatazz, 21 ho as (Ba celona) 30 DE OCTUBRE: Discoteca Joy Eslava, 21 ho as (,ad id) 31 DE OCTUBRE: A.dito io ,aest o Padilla, 21 ho as (Alme 0a) ,a c.s ,ille , Stanley Cla 1e y 20cto 3ooten (S,2) 2enta de ent adas: www.telentrada.com TRES BAJISTAS DE LEYENDA SMV: M.MIller + S.Clarke+ V.Wooten —The Thunder Tour“ el 29 de octubre en Barcelona Sala Razzmatazz; en Madrid el d%a 30 de octubre Sala (oy Esla,a y el 31 de octubre en .lmer%a en el .uditorio Maestro Padilla en su 0esti,al de (azz. Estamos ante .no de los p oyectos m5s impo tantes del a6o, 3 gene aciones de m8sicos y los t es m5s g andes ba:istas del momento e.nidos en lo q.e ya es, seg8n los c 0ticos y el p8blico, .n acontecimiento 8nico. Stanley Cla 1e a tocado con Stan Getz, Joe Hende son, Ho ace Silve , Geo ge D.1e, Keith Richa ds, Pa.l ,cCa tney, Chic1 Co ea con el q.e gan? 1 G ammy@ en 10A2 con , Ret. n To Fo eve :.nto a Aldi ,eola y Lenny 3hite. ,a c.s ,ille a t aba:ado con Robe ta Flac1, A etha F an1lin, Cha1a Khan, 3ayne Sho te , Al Ja ea., Pa.l Simon, David Sanbo n, L.the 2and oss, con el q.e gan? .n G ammy el en a6o 1991, a ,iles Davis le p od.:o y comp.so el alb.m —T.t.“ .no de los alb.mes m5s p emiados de la histo ia del :azz En el a6o 2001 volv0o a gana .n G ammy po el alb.m ,2. -

Intro Pdf. Version

Vertical Harmony Concepts The purpose of this book is to familiarize the bassist with chord structures and to enhance his ability to solo intelligently and effectively. While many of these concepts can be applied to bass lines and fills, these exercises will focus more on soloing. The words "horn-like" are often used to describe solos that are fluid and graceful. To achieve this type of description, one needs to listen to, practice, transcribe and ultimately understand what a soloist is playing. The first step to understanding is knowing chord structures. As bassists, we typically aren't called upon to play chords. So why even know them? That is the question I get from many of my beginning students. Or, "just tell me the root, I'll figure it out from there" which usually means "I'll plod along on the root." We bassists are not only responsible for holding things together rhythmically; we are also the keepers of the harmony. If you don't understand how chords are constructed, how are you going to hold things together? Let alone solo? Playing root notes will only get you so far. Fortunately, knowing what it takes to construct a chord is easy, and by knowing the construction (quality), you should never play a "wrong" note. Intervals are what make up any type of musical structure. Everything you play will involve intervals. An understanding of intervals is essential for understanding music. An interval is the distance between two notes. In Western music there are twelve intervals. Each interval has a numerical identity. -

Automatic Transcription of Bass Guitar Tracks Applied for Music Genre Classification and Sound Synthesis

Automatic Transcription of Bass Guitar Tracks applied for Music Genre Classification and Sound Synthesis Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) vorlelegt der Fakultät für Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Technischen Universität Ilmenau von Dipl.-Ing. Jakob Abeßer geboren am 3. Mai 1983 in Jena Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Gerald Schuller Prof. Dr. Meinard Müller Dr. Tech. Anssi Klapuri Tag der Einreichung: 05.12.2013 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 18.09.2014 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2014000294 ii Acknowledgments I am grateful to many people who supported me in the last five years during the preparation of this thesis. First of all, I would like to thank Prof. Dr.-Ing. Gerald Schuller for being my supervisor and for the inspiring discussions that improved my understanding of good scientific practice. My gratitude also goes to Prof. Dr. Meinard Müller and Dr. Anssi Klapuri for being available as reviewers. Thank you for the valuable comments that helped me to improve my thesis. I would like to thank my former and current colleagues and fellow PhD students at the Semantic Music Technologies Group at the Fraunhofer IDMT for the very pleasant and motivating working atmosphere. Thank you Christian, Holger, Sascha, Hanna, Patrick, Christof, Daniel, Anna, and especially Alex and Estefanía for all the tea-time conversations, discussions, last-minute proof readings, and assistance of any kind. Thank you Paul for providing your musicological expertise and perspective in the genre classification experiments. I also thank Prof. Petri Toiviainen, Dr. Olivier Lartillot, and all the collegues at the Finnish Centre of Excellence in Interdisciplinary Music Research at the University of Jyväskylä for a very inspiring research stay in 2010. -

SMV: Stanley Clarke/Marcus Miller/Victor Wooten

SMV - Stanley Clarke - Marcus Miller - Victor Wooten In an era where sports fantasy leagues are all the rage comes a real-life historic teaming that serious music fans and bass players have long dreamed of. SMV unites music titans Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten. This unique alliance of three generations of bass gods has been on chat room and fan gathering wish lists for over 15 years, kept alive by periodic statements from all three that schedules permitting they would give it a go. Finally, in October 2007, with Clarke set to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award from Bass Player magazine, at its annual Bass Player Live! event in New York City, Miller and Wooten made the time to attend and induct their mentor. The ensuing VSOP jam not only blew the minds of the 900 in attendance, it cemented for the trio their inherent musical chemistry and thus the viability of pursuing the project in earnest. As a result, in January 2008, SMV entered the studio to record a CD and put together a summer/fall tour. The three recall their first performance and the sessions for their disc. Says Clarke, “The second we started ‘School Days’ at the Bass Player event I knew it was historical for us and the audience. Marcus and Victor are so intuitive, and we each found our range. Marcus was slamming down the groove and Victor started playing these harmonics chords, and I was like, man, this is so bad-ass! When you have that amount of knowledge, respect and love it always creates clarity in the music.” Wooten admits, “To work with Stanley and Marcus has been a dream come true for me. -

Peter Erskine & the Lounge Art Ensemble

SONOKLECT '98-'99 A ConcertSeries of Twentieth-CenturyMusic TerryVosbein, Director Peter Erskine & The Lounge Art Ensemble Washingtonand Lee University Keller Theatre • 8 p.m. • 26 September 1998 PROGRAM SetOne SetTwo 3 Peter Erskine began playing the drums at the age of four and has now been at the forefront of world-class jazz ensembles for twenty-six years . His first major professional work was with the Stan Kenton Orchestra, which he joined in 1972. After a three-year stint with Kenton and a two-year stay with Maynard Ferguson, he joined Weather Report in 1978. The excellence of the partnership between Erskine and bassist Jaco Pastorius was an integral part of that group's success. Following his four years in Weather Report (having recorded five albums with them including the Grammy Award winning 8:30),he began to play with Michael Brecker, Mike Mainieri and Eddie Gomez in the group Steps Ahead. His other touring and recording credits (300 albums) include Steely Dan, Chick Corea, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Gary Burton and Pat Metheny, Joni Mitchell, The Boston Pops Orchestra, Ralph Towner, Sadao Watanabe, Hubert Laws, Vanessa Williams, Al DiMeola, Elaine Elias, Miroslav Vitous and Jan Garbarek, Ensemble Modern, as well as Bass Desires (with John Scofield, Bill Frisell and Marc Johnson), the John Abercrombie Trio, Pino Daniele, the Kenny Wheeler Quintet and Big Band, the Bob Mintzer Big Band, in addition to his own groups. 4 Peter has recorded ten solo albums: Peter Erskine, Transition, Motion Poet, Sweet Soul, Big Theatre,and his ECM recordings You Never Know, Time Being, As It Is and Juni as well as History of the Drum on Interworld Music, and FromKenton to Now on his own label, FUZZY MUSIC. -

December 1993

Features DAVE ABBRUZZESE With nary a note on Pearl Jam's breakthrough album, Ten, Dave Abbruzzese flew to the top of MD's 1993 Readers Poll in the Up & Coming category. Now the brand-new Five Against One is out, and Dave's really laying down his mark. • Matt Peiken 20 TONY REEDUS Can today's jazz drummer find happiness on both sides of the avant-garde/straight-ahead coin? Well, Tony Reedus has, making him one of the most sought-after skinsmen around. • Ken Micallef 26 ZILDJIAN AT 370 Zildjian certainly should be proud of their long history: Their cymbal design innovations often coincided with the major artistic leaps of our drumset masters. Since the company is celebrating their deep roots in a big way this year, we thought it a good time to check in. • Rick Van Horn 30 Volume 17, Number 12 Cover Photo By Lance Mercer EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 48 OFF THE 8 UPDATE RECORD Billy Cobham, Mike Portnoy Toss Panos, Lance Huff of David & the Giants, and the Bulletboys' 52 STRICTLY Jim D'Anda, plus News TECHNIQUE The Hi-Hat 138 INDUSTRY BY JOE MORELLO HAPPENINGS 62 DRIVER'S SEAT Big Bands & Bass Drums DEPARTMENTS BY CHARLIE PERRY 4 EDITOR'S 36 PRODUCT OVERVIEW 66 LATIN CLOSE-UP SYMPOSIUM Pearl Masters Maguinho's 6 READERS' Custom Drumkit BY RICK VAN HORN Brazilian Rhythms PLATFORM BY PETE MAGADINI 39 Rhythm Tech 12 ASK A PRO indexTension Drum 94 SHOW Tuners BY ADAM BUDOFSKY DRUMMERS' 16 IT'S SEMINAR QUESTIONABLE Pete Engelhart Crashers Trials & Tribulations BY ADAM BUDOFSKY Of A New York 50 DRUMLINE Show Drummer 40 LP Gajate Bracket BY LARRY CALLAHAN BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 102 CRITIQUE Taw Duplicate X 98 THE JOBBING Products NDEX DRUMMER 126 1993 I BY RICK VAN HORN The Clubdate Business UPDATE BY PETER J.