Swedbank Economic Outlook Is Available At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

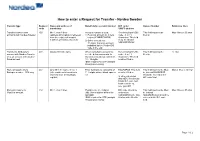

How to Enter a Request for Transfer - Nordea Sweden

How to enter a Request for Transfer - Nordea Sweden Transfer type Request Name and address of Beneficiary’s account number BIC code / Name of banker Reference lines code beneficiary SWIFT address Transfer between own 400 Min 1, max 4 lines Account number is used: Receiving bank’s BIC This field must not be Max 4 lines x 35 char accounts with Nordea Sweden (address information is retrieved 1) Personal account no = pers code - 8 or 11 filled in from the register of account reg no (YYMMDDXXXX) characters. This field numbers of Nordea, Sweden) 2) Other account nos = must be filled in 11 digits. Currency account NDEASESSXXX indicated by the 3-letter ISO code in the end Transfer to third party’s 401 Always fill in the name When using bank account no., Receiving bank’s BIC This field must not be 12 char account with Nordea Sweden see the below comments. In code - 8 or 11 filled in or to an account with another Sweden account nos consist of characters. This field Swedish bank 10 - 15 digits. must be filled in IBAN required for STP (straight through processing) Domestic payments to 402 Only fill in the name in line 1 Enter bankgiro no consisting of BGABSESS. This field This field must not be filled Max 4 lines x 35 char Bankgiro number - SEK only (other address information is 7 - 8 digits without blank spaces must be filled in. in. Instead BGABSESS retrieved from the Bankgiro etc should be entered in the register) In other currencies BIC code field than SEK: Receivning banks BIC code and bank account no. -

Annual Report Annual Report 2020

Annual report Annual report 2020 2 Contents CEO’s review 3 The year 2020 at Verkkokauppa.com 4 Operating environment 5 Verkkokauppa.com’s strategy 6 Business review 7 Sustainability at Verkkokauppa.com 9 Value creation for diverse stakeholders 11 Verkkokauppa.com as an investment 12 Report of the Board of Directors 15 Report of the Board of Directors 16 Non-financial information statement 18 Financial statements 2020 31 Auditor‘s Report 57 Verkkokauppa.com Oyj Remuneration Report 2020 61 Corporate governance statement 65 Corporate Governance statement 66 Board of Directors 72 Management team 74 Annual report 2020 CEO’s review 3 Reaching record-breaking results together volume of customers, we succeeded in improving our Alongside everything else, we worked to update The year 2020 was a strong year of profitable growth customer satisfaction significantly. This was largely thanks our strategy during the year. The year-long process in the exceptional operating environment. Our revenue to our logistics, which operated with nearly peak season defined the Company’s focus areas for the next strategy increased by 10%, and we have 30 consecutive quarters volumes throughout the year. This also gave a good period, during which we aim to increase our revenue to of growth behind us. Our profitability development starting point to create long-term customer relationships. one billion euros and to increase our operating profit to was even stronger, and we reached a record result five percent. We will search for growth by, for instance, in every quarter. Compared to the previous year, our Moving to the Main Market of Nasdaq Helsinki continuing to expand our assortment and market share, like-for-like operating profit increased by 81%. -

Complaint No

EUROPEAN COMMITTEE OF SOCIAL RIGHTS COMITE EUROPEEN DES DROITS SOCIAUX 3 December 2020 Case Document No. 1 Validity v. Finland Complaint No. 197/2020 COMPLAINT Registered at the Secretariat on 27 November 2020 1 Department of the European Social Charter Directorate General Human Rights and Rule of Law Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex E-mail address: [email protected] COLLECTIVE COMPLAINT Validity v. The Republic of Finland on the violation of the rights of persons with disabilities in institutions during the pandemic --- Violation of Articles 11, 14 and 15 in conj. with Article E of European Social Charter COMPLAINANT: Validity Foundation – Mental Disability Advocacy Centre Address: Impact Hub, Ferenciek tere 2, 1053 Budapest, Hungary Contact: tel.: + 36 1 780 5493; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Registered foundation number (Hungary): 8689 In partnership with: Law Firm Kumpuvuori Ltd. Address: Verkatehtaankatu 4, ap. 228, 20100 TURKU, Finland Contact: tel.: +358 50 552 0024; e-mail: [email protected] Registration number (Finland): 2715864-1 European Network on Independent Living - ENIL Address: Mundo J, 7th Floor, Rue de l’Industrie, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Contact: tel: + 32 2 893 25 83; e-mail: [email protected] Registration number (Belgium): 0628829521 2 I. SUMMARY 4 II. ADMISSIBILITY 5 a. Standing of Validity 5 b. Status of the Republic of Finland 6 III. SUBJECT MATTER OF THE COMPLAINT 6 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. THE MEASURES ADOPTED IN REACTION TO THE PANDEMIC 8 a. Prohibition of visits by family members 9 b. Prohibition on leaving all housing service units 12 c. Prohibition of visits by professionals 13 d. -

2019 Annual and Sustainability Report

2019 Annual and Sustainability Report Contents Swedbank in brief 2 Income, balance sheet and notes, Group The year in brief 4 Income statement 54 CEO statement 6 Statement of comprehensive income 55 Goals and results 8 Balance sheet 56 Value creation 10 Statement of changes in equity 57 Business model 12 Statement of cash flow 58 Sustainability 14 Notes 59 The share and owners 24 Income, balance sheet and notes, Parent company Board of Directors’ report Income statement 154 Financial analysis 26 Statement of comprehensive income 154 Swedish Banking 30 Balance sheet 155 Baltic Banking 31 Statement of changes in equity 156 Large Corporates & Institutions 32 Statement of cash flow 157 Group Functions & Other 33 Notes 158 Corporate governance report 34 Alternative performance measures 192 Board of Directors 46 Group Executive Committee 50 Sustainability Disposition of earnings 52 Sustainability report 194 Materiality analysis 195 Sustainability management 197 Notes 199 GRI Standards Index 212 Signatures of the Board of Directors and the CEO 217 Auditors’ report 218 Sustainability report – assurance report 222 Annual General Meeting 223 Market shares 224 Five-year summary – Group 225 Three-year summary – Business segments 228 Definitions 231 Contacts 233 Financial information 2020 Annual General Meeting 2020 Q1 Interim report 23 April The Annual General Meeting will be held on Thursday, 26 March at 11 am (CET) at Cirkus, Djurgårdsslätten Q2 Interim report 17 July 43–45, Stockholm, Sweden. The proposed record day for the dividend is 30 March 2020. The last day for Q3 Interim report 20 October trading in Swedbank’s shares including the right to the dividend is 26 March 2020. -

Íslandsbanki Hf

Proposal summary Swedbank in cooperation with Kepler Cheuvreux are proud to present our offer to act as an Underwriter in a potential IPO of Íslandsbanki Swedbank offers a full suite of Investment Banking services, including advisory, M&A, IPO, IPO financing, project financing, equity and bond issuance, equity and credit trading etc. ABOUT SWEDBANK Applicable Read and understood Consent regarding operating provisions of Act no. publication of ✓ licenses of party ✓ 155/2012 and ✓ advisor’s expression Íslandsbanki’s policy on of interest sustainability SWEDBANK & Swedbank has partnered with Kepler Cheuvreux, a leading European Financial Service Long lasting relationship through KEPLER CHEUVREUX Company with emphasis on equity research and ECM execution, to broaden our extensive advisory service within COOPERATION product offering and international distribution in Europe bond issuance The team is supported by Swedbank CEO Jens Henriksson and is Experienced lead by highly qualified individuals with vast deal experience Cooperation within ESG at the team over the years, including Icelandic deals and government sell highest level – both our CEOs are downs part of ‘Nordic CEOs for a Sustainable Future’ Global Reach The partnership with Kepler Cheuvreux enables us to reach all with Multi- relevant pockets of demand throughout Europe and North Local presence America OUR OFFER – Contact person Kepler Cheuvreux has extensive coverage of all the major banks Best-in-class in Europe, which will include Íslandsbanki and research report Sanna Tunsbrunn research will be distributed on every continent Director, FIG Origination Phone: +46 8 700 93 14 Mobile: +46 72 566 33 78 After- We work in close collaboration with our customers to support Email: [email protected] transaction the companies after they entered a public environment through Address: SE-105 34, Stockholm, Sweden support non-deal roadshows, trading support etc. -

View Annual Report

Swedbank AB Annual Report 2009 Annual Report 2009 Anna Sundblad Johannes Rudbeck CONTACTS 52210011 Group Press Manager Head of Investor Relations Telephone: +46 8 585 921 07 Telephone: +46 8 585 933 22 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Contents 1 Financial summary and important events 2009 2 This is Swedbank 4 President’s statement 8 Fundamental values 9 Strategies and priorities 14 Financial analysis Business areas: 2 1 Swedish Banking 2 5 Baltic Banking 2 9 International Banking 33 Swedbank Markets 3 6 Asset Management 3 8 Ektornet Employees 40 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ REPORT DIRECTORS’ OF BOARD 42 Salaries and incentives 43 Sustainable development 45 The share and owners 48 The Group’s risks and risk control Financial statements and notes: 58 Income statement 59 Statement of comprehensive income 60 Balance sheet 61 Statement of cash flow 62 Statement of changes in equity 63 Notes Financial information 2010 124 Signatures of the Board of Directors and the President Q1 interim report 27 April 125 Auditors’ report Q2 interim report 22 July 126 Board of Directors Q3 interim report 21 October 128 Group Executive Committee 129 Corporate governance report Annual General Meeting 136 Market shares The Annual General Meeting 2010 will be held at 138 Five-year summary - Group Berwaldhallen, Stockholm, on Friday, 26 March. 140 Two-year summary - Business areas 145 Annual General Meeting 146 Definitions 148 Addresses Swedbank’s annual report is offered to all new shareholders and distributed to those who have actively chosen to receive it. The interim reports are not printed, but are available at www.swedbank.se/ir, where the annual report can also be ordered. -

Harvia Plc Annual Report 2020 Contents

HARVIA PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CONTENTS Highlights of 2020 3 Harvia in 2020 6 CEO’s review 8 Operating environment and megatrends 10 Strategy and its implementation 14 Harvia’s business operations in 2020 17 R&D, innovations and new products 22 Sustainability 25 Harvia as an investment 31 Corporate Governance Statement 2020 35 Remuneration Report 2020 46 Report by the Board of Directors and Consolidated Financial Statements 2020 50 Cover: Aurora Village, Ivalo, Finland, photo: Veikka Hännikäinen This page: Villa Fortuna, Tuusula, Finland, Harvia steam room Back cover: Almost Heaven Saunas Audra Canopy barrel sauna, California, USA 3 HIGHLIGHTS OF 2020 Almåsa Havshotell, Ruotsi 4 SIGNIFICANT INCREASE IN REVENUE AND and distribution of EOS will remain independent. PROFITABILITY The acquisition complements Harvia’s one stop shop offering with EOS’s professional and premium Harvia’s revenue and profitability increased solutions. Harvia became the number one player in significantly during the year. The exceptionally professional saunas and the sauna experience. positive development was boosted by the pandemic and the wellness trend. Regarding net sales, Harvia INTERNATIONALIZATION AWARD OF THE has reached a position at par with the largest player PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FINLAND in the sauna and spa industry globally. The skills and efforts of Harvia personnel have been truly noted and in November, Harvia was granted ACQUISITION OF EOS GROUP CREATES NEW the Internationalization Award of the President of GROWTH OPPORTUNITIES the Republic of Finland. Recognized as a growth In April 2020, Harvia acquired the majority of company, Harvia has developed in 70 years from the German technology leader in sauna and spa a small domestic sauna heater manufacturer into equipment, EOS Group. -

Victor Carlstrom VS SWEDBANK and Folksam and Other Swedish Officials

Case 1:19-cv-11569 Document 1 Filed 12/17/19 Page 1 of 74 LAWRENCE H. SCHOENBACH, ESQ. Law Offices of Lawrence H. Schoenbach 111 Broadway, Suite 901 New York, New York 10006 JOSHUA L. DRATEL, ESQ. Dratel & Lewis, P.C. 29 Broadway, Suite 1412 New York, New York 10006 Attorneys for Victor Carlström, Stephen Brune , Vinacossa Enterprises AB, SBS Resurs Direkt AB, Boflexibilitet Sverige AB, Vinacossa Enterprises Ltd, and Sparflex AB UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK __________________________________________ ) VICTOR CARLSTRÖM, STEPHEN BRUNE, ) VERIFIED COMPLAINT VINACOSSA ENTERPRISES AB, ) AND JURY DEMAND VINACOSSA ENTERPRISES LTD, ) RICO (18 U.S.C.§1962(c)) BOFLEXIBILITET SVERIGE AB, SBS ) RICO CONSPIRACY RESURS DIREKT AB and SPARFLEX AB. ) (18 U.S.C.§1962(d)) ) COMPUTER FRAUD AND Plaintiffs, ) ABUSE ACT ) (18 U.S.C.§1030(a)) - Against – ) BREACH OF CONTRACT ) (NEW YORK COMMON LAW) ) TORTIOUS INTERFERENCE FOLKSAM ÖMSESIDIG LIVFÖRSÄKRING, ) WITH CONTRACT SWEDBANK AB, SKATTEVERKET, ) (NEW YORK COMMON LAW) FINANSINSPEKTIONEN, JENS ) TORTIOUS INTERFERENCE HENRIKSSON, ERIK THEDÉEN, KATRIN ) WITH COMPETITIVE WESTLING PALM and others known and ) ADVANTAGE (NEW YORK unknown. ) COMMON LAW) ) INTENTIONAL INFLICTION OF Defendants. ) EMOTIONAL DISTRESS ) (NEW YORK COMMON LAW) __________________________________________) Plaintiffs VICTOR CARLSTRÖM, STEPHEN BRUNE, BO FLEXIBILITET SVERIGE AB, VINACOSSA ENTERPRISES AB, VINACOSSA ENTERPRISES LTD, SBS RESURS 1 Case 1:19-cv-11569 Document 1 Filed 12/17/19 Page 2 of 74 DIREKT AB and SPARFLEX AB, allege the following against defendants FOLKSAM ÖMSESIDIG LIVFÖRSÄKRING (“Folksam”), SWEDBANK AB, SKATTEVERKET, FINANSINSPEKTIONEN, JENS HENRIKSSON, ERIK THEDÉEN, KATRIN WESTLING PALM and others known and unknown. JURISDICTION Subject Matter Jurisdiction 1. This Court has federal question jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. -

Popis Trećih Osoba S Kojima Su Sklopljeni Ugovori O Delegiranju Poslova Skrbništva (Podskrbnici)

OTP banka d.d. Domovinskog rata 6, 21000 Split, Croatia MB 3141721, OIB 52508873833 SWIFT: OTPVHR2X Popis trećih osoba s kojima su sklopljeni ugovori o delegiranju poslova skrbništva (podskrbnici) Tržište podskrbnik OTP banke d.d. Krajnji skrbnik SWIFT Clearstream Banking Luxembourg CAJA DE VALORES S.A. CAVLARBAXXX Argentina Societe Generale SA CITIBANK N.A. BUENOS AIRES CITIARBAXXXX The Bank of New York Mellon Brussels HSBC BANK AUSTRALIA LIMITED HKBAAU2SXXX Clearstream Banking Luxembourg JPMORGAN CHASE BANK, N.A. (SYDNEY BRANCH) CHASAU2XDCC Australija Clearstream Banking Luxembourg BNP Paribas Securities Services PARBAU2SXXX Societe Generale SA CITICORP NOMINEES PTY LIMITED CITIAU3XXXX The Bank of New York Mellon Brussels UNICREDIT BANK AUSTRIA AG BKAUATWWXXX Clearstream Banking Luxembourg ERSTE GROUP BANK AG GIBAATWGXXX Austrija Clearstream Banking Luxembourg CLEARSTREAM BANKING AG, FRANKFURT DAKVDEFFXXX Societe Generale SA UNICREDIT BANK AUSTRIA – VIENNA BKAUATWWXXX Societe Generale SA EUROCLEAR BANK SA/NV MGTCBEBEECL Bahrein Societe Generale SA HSBC BANK MIDDLE EAST LIMITED BBMEBHBXXXX The Bank of New York Mellon Brussels NATIONAL BANK OF BELGIUM IRVTBEBBDCP The Bank of New York Mellon Brussels EUROCLEAR BELGIUM IRVTBEBBDCP Clearstream Banking Luxembourg BNP PARIBAS SECURITIES SERVICES, PARIS PARBFRPPXXX Belgija Clearstream Banking Luxembourg CLEARSTREAM BANKING AG, FRANKFURT DAKVDEFFXXX Clearstream Banking Luxembourg KBC BANK NV KREDBEBBXXX Societe Generale SA SOCIETE GENERALE FRANCE SOGEFRPPINV Societe Generale SA EUROCLEAR BANK -

Swedbank´S Annual and Sustainability Report 2018

2018 Compiled Sustainability Information This document compiles all the sustainability information presented in Swedbank´s Annual and Sustainability Report 2018. The document is developed to facilitate for our stakeholders to find information about the bank´s sustain ability efforts, increase transparency and give us an oppor tunity to report on how we work with and implement sustaina bility in our business. The report conforms to the Global Reporting Initiative´s (GRI) guidelines, version Standards, Core level and has been reviewed by Deloitte AB. Swedbank Compiled Sustainability Information 2018 Content 14 Sustainability – part of Swedbank’s heritage and purpose 17 The work with TCFD 18 Swedbank and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals 188 Sustainability report 189 Materiality analysis 190 Stakeholder engagement 191 Material impacts and strategic policy documents 191 Precautionary principle 192 Sustainability management 194 S1 – Pay 195 S2 – Save/Invest 197 S3 – Finance 198 S4 – Procure 198 S5 – Environmental impacts 200 S6 – Employees 202 S7 – IT security and crime prevention 202 S8 – Anti-corruption 203 S9 – Taxes 203 S10 – Human rights 204 S11 – Social engagement 205 GRI Standards Index 206 GRI Topic-specific disclosures 214 Assurance report 225 Contacts Swedbank Compiled Sustainability Information 2018 14 SUSTAINABILITY Sustainability – part of Swedbank’s heritage and purpose Strong social engagement and clear values distinguish Swedbank in Sweden and the Baltic countries. Back when the first Swedish savings bank was founded, in 1820, the objective was to give the public a way to build savings for the long term. This social commitment has also applied to the Baltic countries from the beginning, with Hansabank, which was founded in 1991 and later became part of Swedbank. -

Disciplinary Committee of Nasdaq Stockholm

May 5, 2021 Decision by the Disciplinary Committee of Nasdaq Stockholm The Disciplinary Committee at Nasdaq Stockholm today ordered Swedbank to pay a fine of twelve annual fees, equivalent of SEK 46.6 million. As Swedbank stated in its Q1- report on April 27, the issue concerns historical matters dating back to 2016-2019. The Disciplinary Committee states that Swedbank over a long period of time had shortcomings in its AML processes and routines and that the shortcomings were known to the bank’s former top management for a long period of time. During March, Nasdaq Stockholm AB (Nasdaq) informed the bank of the conclusions of its review as to whether the bank had breached the Nasdaq’s rules during the period December 2016 to February 2019. Later, the review was handed over to the Disciplinary Committee of Nasdaq Stockholm which has now decided the matter. Swedbank stated in the quarterly report on April 27 that the bank largely concurs with Nasdaq’s conclusions. ”During the last year, the bank has undertaken several measures to strengthen processes for the disclosure of information. Today’s decision means that yet another issue concerning the bank’s historical shortcomings, is closed,” says Jens Henriksson, President and CEO of Swedbank. As the bank communicated in the quarterly report on April 27, 2021, the bank expected that the Disciplinary Committee of Nasdaq Stockholm would decide on a fine and therefore allocated SEK 30 million for the purpose. Contact information: Annie Ho, Head of Investor Relations, +46 70 343 78 15 Unni Jerndal, Head of Group Press Office, +46 73 092 11 80 Swedbank AB (publ) is required to disclose this information pursuant to the Swedish Securities Markets Act (2007:528), the Swedish Financial Instruments Trading Act (1991:980) and the regulatory framework of Nasdaq Stockholm. -

Citibank Europe Plc, Luxembourg Branch: List of Sub-Custodians

Citibank Europe plc, Luxembourg Branch: List of Sub-Custodians Country Sub-Custodian Argentina The Branch of Citibank, N.A. in the Republic of Argentina Australia Citigroup Pty. Limited Austria Citibank Europe plc, Dublin Bahrain Citibank, N.A., Bahrain Bangladesh Citibank, N.A., Bangaldesh Belgium Citibank Europe plc, UK Branch Benin Standard Chartered Bank Cote d'Ivoire Bermuda The Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited acting through its agent, HSBC Bank Bermuda Limited Bosnia-Herzegovina (Sarajevo) UniCredit Bank d.d. Bosnia-Herzegovina: Srpska (Banja Luka) UniCredit Bank d.d. Botswana Standard Chartered Bank of Botswana Limited Brazil Citibank, N.A., Brazilian Branch Bulgaria Citibank Europe plc, Bulgaria Branch Burkina Faso Standard Chartered Bank Cote D'ivoire Canada Citibank Canada Chile Banco de Chile China B Shanghai Citibank, N.A., Hong Kong Branch (For China B shares) China B Shenzhen Citibank, N.A., Hong Kong Branch (For China B shares) China A Shares Citibank China Co ltd ( China A shares) China Hong Kong Stock Connect Citibank, N.A., Hong Kong Branch Clearstream ICSD ICSD Colombia Cititrust Colombia S.A. Sociedad Fiduciaria Costa Rica Banco Nacioanal de Costa Rica Croatia Privedna banka Zagreb d.d. Cyprus Citibank Europe plc, Greece Branch Czech Republic Citibank Europe plc, organizacni slozka Denmark Citibank Europe plc, Dublin Egypt Citibank, N.A., Cairo Branch Estonia Swedbank AS Euroclear ICSD 1 Citibank Europe plc, Luxembourg Branch: List of Sub-Custodians Country Sub-Custodian Finland Nordea Bank AB (publ), Finish Branch France Citibank Europe plc, UK Branch Georgia JSC Bank of Georgia Germany Citibank Europe plc, Dublin Ghana Standard Chartered Bank of Ghana Limited Greece Citibank Europe plc, Greece Branch Guinea Bissau Standard Chartered Bank Cote D'ivoire Hong Kong Citibank NA Hong Kong Hungary Citibank Europe plc Hungarian Branch Office Iceland Citibank is a direct member of Clearstream Banking, which is an ICSD.