Hopper Mountain National Wildlife Refuge Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciprocal Zoo List 2019 for Website

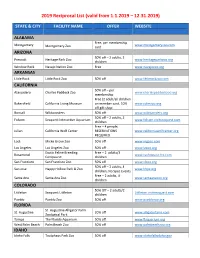

2019 Reciprocal List (valid from 1.1.2019 – 12.31.2019) STATE & CITY FACILITY NAME OFFER WEBSITE ALABAMA Free, per membership Montgomery www.montgomeryzoo.com Montgomery Zoo card ARIZONA 50% off – 2 adults, 3 Prescott Heritage Park Zoo www.heritageparkzoo.org children Window Rock Navajo Nation Zoo Free www.navajozoo.org ARKANSAS Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% off www.littlerockzoo.com CALIFORNIA 50% off – per Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo www.charlespaddockzoo.org membership Free (2 adult/all children Bakersfield California Living Museum on member card, 10% www.calmzoo.org off gift shop Bonsall Wildwonders 50% off www.wildwonders.org 50% off – 2 adults, 2 Folsom Seaquest Interactive Aquarium www.folsom.visitseaquest.com children Free – 4 people; Julian California Wolf Center RESERVATIONS www.californiawolfcenter.org REQUIRED Lodi Micke Grove Zoo 50% off www.mgzoo.com Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% off www.lazoo.org Exotic Feline Breeding Free – 2 adults/3 Rosamond www.cathopuise.fcc.com Compound children San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% off www.sfzoo.org 50% off – 2 adults, 4 San Jose Happy Hollow Park & Zoo www.hhpz.org children, No Spec Events Free – 2 adults, 4 Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo www.santaanazoo.org children COLORADO 50% Off – 2 adults/2 Littleton Seaquest Littleton Littleton.visitseaquest.com children Pueblo Pueblo Zoo 50% off www.pueblozoo.org FLORIDA St. Augustine Alligator Farm St. Augustine 20% off www.alligatorfarm.com Zoological Park Tampa The Florida Aquarium 50% off www.flaquarium.org West Palm Beach Palm Beach Zoo 50% off www.palmbeachzoo.org IDAHO Idaho Falls Tautphaus Park Zoo 50% off www.idahofallsidaho.gov 2019 Reciprocal List (valid from 1.1.2019 – 12.31.2019) Free – 2 adults, 5 Pocatello Pocatello Zoo www.zoo.pocatello.us children ILLINOIS Free – 2 adults, 3 Springfield Henson Robinson Zoo children. -

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits List created by © birdsandbats on www.zoochat.com. Last Updated: 19/08/2019 African Clawless Otter (2 holders) Metro Richmond Zoo San Diego Zoo American Badger (34 holders) Alameda Park Zoo Amarillo Zoo America's Teaching Zoo Bear Den Zoo Big Bear Alpine Zoo Boulder Ridge Wild Animal Park British Columbia Wildlife Park California Living Museum DeYoung Family Zoo GarLyn Zoo Great Vancouver Zoo Henry Vilas Zoo High Desert Museum Hutchinson Zoo 1 Los Angeles Zoo & Botanical Gardens Northeastern Wisconsin Zoo & Adventure Park MacKensie Center Maryland Zoo in Baltimore Milwaukee County Zoo Niabi Zoo Northwest Trek Wildlife Park Pocatello Zoo Safari Niagara Saskatoon Forestry Farm and Zoo Shalom Wildlife Zoo Space Farms Zoo & Museum Special Memories Zoo The Living Desert Zoo & Gardens Timbavati Wildlife Park Turtle Bay Exploration Park Wildlife World Zoo & Aquarium Zollman Zoo American Marten (3 holders) Ecomuseum Zoo Salomonier Nature Park (atrata) ZooAmerica (2.1) 2 American Mink (10 holders) Bay Beach Wildlife Sanctuary Bear Den Zoo Georgia Sea Turtle Center Parc Safari San Antonio Zoo Sanders County Wildlife Conservation Center Shalom Wildlife Zoo Wild Wonders Wildlife Park Zoo in Forest Park and Education Center Zoo Montana Asian Small-clawed Otter (38 holders) Audubon Zoo Bright's Zoo Bronx Zoo Brookfield Zoo Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Dallas Zoo Denver Zoo Disney's Animal Kingdom Greensboro Science Center Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens 3 Kansas City Zoo Houston Zoo Indianapolis -

2017 Reciprocal List

2017 Reciprocal List In order to expand your membership experience, The Zoo in Forest Park and Education Center has partnered with zoos, aquariums, museums, and parks across the United States to offer discounted admission to its traveling members for 2017. As reciprocity status is subject to change, please call ahead to verify pricing and hours. Be prepared to show current membership card and valid photo ID at all locations. Traveling members are subject to all rules and regulations set by participating locations. For more information regarding your membership and membership benefits, please contact Nicholas Kinsman at (413) 733-2251, ext. 304, or [email protected] Arizona Orange County Zoo – (714) 973-6841 Heritage Park Zoological Sanctuary – 1 Irvine Park Road (928) 778-4242 Orange, CA 92862 1403 Heritage Park Road Discount: 100% Prescott, AZ 86301 - Excludes special events Discount: 50% - Does not include parking - Excludes special events Santa Ana Zoo – (714) 953-8555 Reid Park Zoo – (520) 881-4753 1801 E. Chestnut Avenue 3400 E Zoo Court Santa Ana, CA 92701 Tucson, AZ 85716 Discount: 100% Discount: 50% - Discount applies to regular daily admission Connecticut - Excludes special events Beardsley Zoo – (203) 394-6565 California 1875 Noble Avenue Bridgeport, CT 06610 Micke Grove Zoo – (209) 331-2010 Discount: 100% 11793 N. Micke Grove Road - Covers admission of 2 adults & up to 6 children Lodi, CA 95240 - Parking is free Discount: 100% Florida Happy Hollow Park & Zoo – (408) 794-6444 1300 Senter Road St. Augustine Alligator Farm - (904) 842-3337 San Jose, CA 95112 999 Anastasia Boulevard Discount: 50% St. Augustine, FL 32080 Discount: 50% Big Bear Alpine Zoo – (909) 878-4200 43285 Goldmine Drive Illinois Big Bear Lake, CA 92315 Discount: 50% Cosely Zoo - (630) 665-5534 - Valid for 2 adults & up to 2 children 1356 N. -

Overview of the Acorn Group, Inc. Blending the Skills of Planners

Overview of The Acorn Group, Inc. Blending the skills of planners, designers, and educators, The Acorn Group offers award-winning services in interpretive planning and design. Part art, part science, accented with storytelling and exquisite design, our interpretive master plans, exhibits, panels, and programs create sensory-rich experiences that bring your content to life. Established in 1990, The Acorn Group is dedicated to the field of interpretation and actively in- volved in the National Association for Interpretation, as well as other professional organizations. Our clients are diverse, ranging from government agencies to private and non-profit institutions. Project sites include interpretive centers, ecological reserves, museums, botanical gardens, zoos, parklands, and educational institutions. Our greatest satisfaction comes from seeing plans and drawings become reality and watching visitors take delight in new experiences. The Acorn Group’s projects and efforts have been recognized nationally, receiving such awards as the Exhibit Design Award, Print and Media Award, and Interpretive Media Award by the National Association for Interpretation, Award of Excellence by the American Society of Landscape Archi- tects, Best of Show by the Western Fairs Association, Award of Excellence by the California Parks and Recreation Society, and National Education Award by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums. The Orange County League of Conservation Voters presented The Acorn Group with the Orange County Environmental Business of the Year Award in 2005. In 2007, The Acorn Group received the First Place Interpretive Media Award from the National Association for Interpretation for design of Nix Nature Center. In 2012, the North American Association for Environment Education presented The Acorn Group and Acorn Naturalists with their Outstanding Service Award. -

Cities and Joint Powers Committee Mission Statement

CITIES AND JOINT POWERS COMMITTEE MISSION STATEMENT The Cities and Joint Powers Committee of the 2014-2015 Grand Jury is responsible for reviewing and overseeing the eleven incorporated cities and the joint powers agreements within the County of Kern pursuant to California Penal Code §925a. The Committee investigates and reports on the records, accounts, officers, departments and functions of the eleven cities and files final reports with possible recommendations. In addition, the Committee is also responsible for investigating and responding to complaints from private county residents. Scott Shaw, Chairman Loretta Avery Sandra Essary 51 CITIES AND JOINT POWERS COMMITTEE SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES The Cities and Joint Powers Committee has written and published the following reports: California Living Museum City of Arvin City of Bakersfield Parks & Recreation McMurtrey Aquatic Center City of California City City of Ridgecrest City of Shafter City of Taft City of Wasco The Cities and Joint Powers Committee handled 2 complaints. The members of the Committee were also involved in numerous other committees and projects during the year. The total of investigative miles traveled by the Committee 715 miles. 52 CALIFORNIA LIVING MUSEUM CALM PLANS EXCITING FUTURE PREFACE: The California Living Museum (CALM) is one of California’s zoos that features flora, fauna, and fossils native to California and, more specifically, to Kern County. CALM exists to teach respect for all living things through education, recreation, conservation, and research. Setting it apart from many zoos is the fact that the animals permanently featured at CALM are ones that cannot be released back into the wild. In addition to being unreleasable, some of the animals at CALM are endangered, which provides the public a chance to learn about animals that they would not otherwise see. -

Table of Contents

Resource Caregiver Family Guide to Services 2021 100 E. California Avenue - P.O. Box 511 - Bakersfield, CA 93302 www.KCDHS.org Kern County Department of Human Services is an equal opportunity employer. Vision: Resource Caregiver Family Every child, individual, and family in Guide Services also available on- Kern County is safe, healthy, and self- line: sufficient. County of Kern website Mission: Department of Human Services The Department of Human Services www.KCDHS.org partners with children, individuals, families and the community to provide customer-centered services. We work to ensure safe, protected and permanent homes for children and we actively assist individuals as they prepare for employment. Values: Be sure to click on the information Service excellence Proactive leadership link under Foster Family Resources Continuous learning and select Caregiver Resource Guide. Diversity Creative solutions Clear goals Measurable results (Department staff can also access this Effective communication guide internally through the intranet.) Constructive feedback Honesty Personal/Professional integrity Accountability Adherence to policy and regulation Responsible stewardship Respect for the individual To report any additions or edits to the contents of this directory contact: Melissa Soin 661-873-2382 To ALL Resource Families: Whether you are a relative/kinship caregiver, a non-related extended family member (NREFM) or a resource family approved caregiver, YOU ARE IMPORTANT and although the steps you took to become a caregiver for a child in foster care may be different, we welcome you as part of the DHS TEAM of Resource Families. THANK YOU for the valuable services you provide to families in times of temporary crises. -

Institution Discount Institution Discount Happy Hollow Park & Zoo 50% Off Kern County Museum

2021 Show your Lindsay Wildlife membership card at any of the following institutions and receive the stated discounts. Institution Discount Institution Discount Happy Hollow Park & Zoo Kern County Museum 1300 Senter Rd, San Jose, CA 95112 (408) 50% off 3801 Chester Avenue, Bakersfield, CA 93301 FREE 794-6444 www.hhpz.orG (661) 852-5000 www.kcmuseum.orG Children’s Creativity Museum Kidspace Children’s Museum 221 Fourth Street, San Francisco, CA 94103 50% off 480 N. Arroyo Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91103 FREE (415) 820-3320 www.creativity.orG (626) 449-9144 www.kidspacemuseum.orG The Lawrence Hall of Science Lick OBservatory 1 Centennial Drive, UC Berkeley, 94720 50% off 29955 Mount Hamilton Rd, Mt Hamilton 95140 FREE (510) 642-5132 www.lawrencehallofscience.orG (831) 459-5939 www.ucolick.orG The Tech Museum of Innovation Maturango Museum of Indian Wells Valley 201 South Market Street, San Jose, CA 95113 50% off 100 East Las Flores Ave, RidGecrest, CA 93555 FREE (408) 794-TECH www.thetech.orG (760) 375-6900 www.maturanGo.orG CALM California Living Museum MOXI: Wolf Museum of Exploration + Innovation 10500 Alfred Harrell HiGhway Bakersfield, CA 93306 FREE 125 State Street, Santa Barbara, CA 93101 FREE (661)-872-2256 www.calmzoo.orG (805) 770-5000 www.moxi.orG California Science Center Natural History Museum:La Brea Tar Pits 700 Exposition Park Drive, Los AnGeles, CA 90037 FREE 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los AnGeles, CA 90007 FREE (323) 724-3623 www.californiasciencecenter.orG (213) 763-3426 www.nhm.orG Children's Museum at La HaBra Placer Nature -

ASTC Travel Passport Program Participants

ASTC Travel Passport Program Participants – November 1, 2016 to April 30, 2017 California List Only—Local Restrictions May Apply The Travel Passport Program entitles visitors to free GENERAL ADMISSION. It does not include free admission to special exhibits, planetarium and larger-screen theater presentations nor does it include museum store discounts and other benefits associated with museum membership unless stated otherwise. Acquaint yourself with the family admittance policies (denoted by “F:”) of Passport Program sites before visiting. Visit www.astc.org/passport for a list in larger font. PROGRAM RESTRICTIONS: 1. Based on your science center’s/museum’s location: Science centers/museums located within 90 miles of each other are excluded from the Travel Passport Program unless that exclusion is lifted by mutual agreement. 90 miles is measured “as the crow flies” and not by driving distance. Science centers/museums may create their own local reciprocal free-admission program. ASTC does not require or participate in these agreements, or dictate their terms. 2. Based on residence: To receive Travel Passport Program benefits, you must live more than 90 miles away “as the crow flies” from the center/museum you wish to visit. Admissions staff reserve the right to request proof of residence for benefits to apply. Science centers and museums requesting proof of residence are marked by (IDs). For Lindsay Wildlife Experience members—ASTC is an international program; a complete list of participating U.S. and international museums is available at the museum, online (www.astc.org/passport), or call 925-935-1978 to have a complete list sent to you. -

Reciprocal and Free Zoos

NMBPS RECIPROCAL LIST for 201 4 --All facilities offer 50% off regular admission and must show valid ID to enter facilities Please remember to bring your NMBPS HAWAII MISSOURI Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium membership card with you when you visit Waikiki Aquarium Dickerson Park Zoo Zoo America in order to receive your member benefits. IDAHO Endangered Wolf Center RHODE ISLAND *free admission Pocatello Zoo Kansas City Zoo Roger Williams Park & Zoo **free and/or discounts for stores, Tautphaus Park Zoo St. Louis Zoo ** SOUTH CAROLINA andattractions, benefits and/or parkingfor the reciprocal program. Zoo Boise MONTANA Greenville Zoo ALABAMA ILLINOIS Zoo Montana Riverbanks Zoo & Garden Birmingham Zoo Cosley Zoo * NEBRASKA SOUTH DAKOTA Montgomery Zoo Henson Robinson Zoo Lincoln Children’s Zoo Bramble Park Zoo ALASKA Lincoln Park Zoo ** Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo Great Plains Zoo & Delbridge Museum Alaska SeaLife Center Miller Park Zoo Riverside Discovery Center TENNESSEE ARIZONA Niabi Zoo NEW HAMPSHIRE Chattanooga Zoo PLEASE NOTE: Heritage Park Zoological Sanctuary Peoria Zoo Squam Lakes Natural Science Center Knoxville Zoo Participation in the Reid Park Zoo Scovill Zoo NEW JERSEY Memphis Zoo reciprocal program with The Navajo Nation Zoo & INDIANA Bergen County Zoological Park Nashville Zoo @ Grassmere the NMBPS is voluntary. Botanic Garden * Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo Cape May County Park & Zoo* TEXAS Occasionally, zoos and The Phoenix Zoo Mesker Park Zoo & Botanic Garden ** Turtle Back Zoo Abilene Zoo ARKANSAS Potawatomi Zoo NEW MEXICO Caldwell Zoo aquariums decide they Little Rock Zoo Washington Park Zoo Alameda Park Zoo Cameron Park Zoo wish to change their CALIFORNIA IOWA Living Desert Zoo & Garden State Park Dallas Zoo participation. -

Institution Discount Institution Discount Oakland Zoo 50% Off Kern County

2017 Show your Lindsay Wildlife membership card at any of the following institutions and receive the stated discounts. Institution Discount Institution Discount Oakland Zoo Kern County Museum 9777 Golf Links Road Oakland, CA.94605 50% off 3801 Chester Avenue, Bakersfield, CA 93301 FREE (510) 632-9525 www.oaklandzoo.org (661) 852-5000 www.kcmuseum.org Happy Hollow Park & Zoo Kidspace Children’s Museum 1300 Senter Rd, San Jose, CA 95112 50% off 480 N. Arroyo Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91103 FREE (408) 794-6444 www.hhpz.org (626) 449-9144 www.kidspacemuseum.org Children’s Creativity Museum Lick Observatory 221 Fourth Street, San Francisco, CA 94103 50% off 29955 Mount Hamilton Rd, Mt Hamilton 95140 FREE (415) 820-3320 www.creativity.org (831) 459-5939 www.ucolick.org The Lawrence Hall of Science Maturango Museum of Indian Wells Valley 1 Centennial Drive, UC Berkeley, 94720 50% off 100 East Las Flores Ave, Ridgecrest, CA 93555 FREE (510) 642-5132 www.lawrencehallofscience.org (760) 375-6900 www.maturango.org The Tech Museum of Innovation Micke Grove Zoo 201 South Market Street, San Jose, CA 95113 50% off 11793 N. Micke Rd. Lodi CA, 95240 FREE (408) 794-TECH www.thetech.org (209)953-8840 www.mgzoo.com CALM California Living Museum MOXI: Wolf Museum of Exploration + Innovation 10500 Alfred Harrell Highway Bakersfield, CA 93306 FREE 125 State Street, Santa Barbara, CA 93101 FREE (661)-872-2256 www.calmzoo.org (805) 770-5000 www.moxi.org California Science Center Natural History Museum:La Brea Tar Pits 700 Exposition Park Drive, Los Angeles, CA -

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

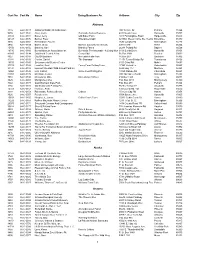

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 3316 64-C-0117 Alabama Wildlife Rehabilitation 100 Terrace Dr Pelham 35124 9655 64-C-0141 Allen, Keith Huntsville Nature Preserve 431 Clouds Cove Huntsville 35803 33483 64-C-0181 Baker, Jerry Old Baker Farm 1041 Farmingdale Road Harpersville 35078 44128 64-C-0196 Barber, Peter Enterprise Magic 621 Boll Weevil Circle Ste 16-202 Enterprise 36330 3036 64-C-0001 Birmingham Zoo Inc 2630 Cahaba Rd Birmingham 35223 2994 64-C-0109 Blazer, Brian Blazers Educational Animals 230 Cr 880 Heflin 36264 15456 64-C-0156 Brantley, Karl Brantley Farms 26214 Pollard Rd Daphne 36526 16710 64-C-0160 Burritt Museum Association Inc Burritt On The Mountain - A Living Mus 3101 Burritt Drive Huntsville 35801 42687 64-C-0194 Cdd North Central Al Inc Camp Cdd Po Box 2091 Decatur 35602 3027 64-C-0008 City Of Gadsden Noccalula Falls Park Po Box 267 Gadsden 35902 41384 64-C-0193 Combs, Daniel The Barnyard 11453 Turner Bridge Rd Tuscaloosa 35406 19791 64-C-0165 Environmental Studies Center 6101 Girby Rd Mobile 36693 37785 64-C-0188 Lassitter, Scott Funny Farm Petting Farm 17347 Krchak Ln Robertsdale 36567 33134 64-C-0182 Lookout Mountain Wild Animal Park Inc 3593 Hwy 117 Mentone 35964 12960 64-C-0148 Lott, Carlton Uncle Joes Rolling Zoo 13125 Malone Rd Chunchula 36521 22951 64-C-0176 Mc Wane Center 200 19th Street North Birmingham 35203 7051 64-C-0185 Mcclelland, Mike Mcclellands Critters P O Box 1340 Troy 36081 3025 64-C-0003 Montgomery Zoo P.O. -

Use of Dna Sequencing to Identify the Origin of Northwestern and Southwestern Pond Turtles in Captive Breeding Programs

ABSTRACT USE OF DNA SEQUENCING TO IDENTIFY THE ORIGIN OF NORTHWESTERN AND SOUTHWESTERN POND TURTLES IN CAPTIVE BREEDING PROGRAMS Captive breeding is a critical management strategy in the recovery and preservation of certain threatened and endangered species. Programs that implement captive breeding must maintain a balance between preserving the genetic purity and genetic diversity of a population in order to build a viable group of individuals for future reintroduction. This may be difficult due to a limited number of extant wild individuals for establishment of founder populations, leading to an increased risk of inbreeding or outbreeding depression in subsequent generations. In this study, I worked in collaboration with 24 zoos, museums, and aquariums through the Western Pond Turtle Species Survival Plan Sustainability Project to aid in conservation of two threatened and endangered freshwater turtle species through captive breeding. As individuals of the two different species can appear morphologically identical, I used DNA sequencing to identify wild-bred Northwestern (Actinemys marmorata) and Southwestern Pond Turtles (Actinemys pallida) to build captive brood stock of both species. Relatively few studies have assessed conservation efforts in consideration of two genetically distinct species within the genus Actinemys as the majority of research on this clade was done before the discovery of a second species. Here, I analyzed the nicotinamide adenine dehydrogenase subunit four (ND4) mitochondrial gene to identify species and geographic origin for 133 captive pond turtles including 71 members of A. marmorata and 62 A. pallida individuals. Results of this study were used to inform captive breeding program collaborators so that husbandry is managed in consideration of species, geographic origin, and the subsequent risks of outbreeding and inbreeding depression.