Developing Sense of Place in USA Zoos: Effect of Featuring Local Versus Exotic Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1875 El Prado San Diego, CA 92101 (619) 238-1233

Volunteer Orientation Handbook 1875 El Prado San Diego, CA 92101 (619) 238-1233 www.rhfleet.org The Reuben H. Fleet Science Center seeks to inspire lifelong learning by furthering the public understanding and enjoyment of science and technology. Welcome Welcome to the Volunteer and Internship Programs at the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center. We thank you for your interest in helping our organization inspire lifelong learning in our community. We sincerely hope that your experiences here will be rewarding, educational and fun! Volunteers and interns play an integral role in the operation of the Fleet and its programs. Our team is made up of over 200 dedicated volunteers and interns (and roughly 100 employees) serving in a multitude of roles, all helping to spark a better understanding and enjoyment of science and technology by the public. We would like to express our sincere appreciation for your interest in our volunteer and intern programs. We couldn't do any of this without your support. THANK YOU for sharing your time and talent with us! General Information Mission Statement: The Reuben H. Fleet Science Center seeks to inspire lifelong learning by furthering the public understanding and enjoyment of science and technology. Physical Address: 1875 El Prado (at the intersection of Park Blvd. & Space Theater Way) San Diego, CA 92101 Mailing Address: PO Box 33303 San Diego, CA 92163 Telephone: (619) 238-1233 Website: www.rhfleet.org Hours: Open every day, including holidays! We open every day at 10:00 a.m. (exception: 11:30 a.m. on Christmas day). Closing times vary—check our website for updates. -

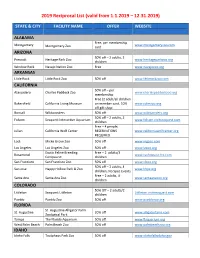

Reciprocal Zoo List 2019 for Website

2019 Reciprocal List (valid from 1.1.2019 – 12.31.2019) STATE & CITY FACILITY NAME OFFER WEBSITE ALABAMA Free, per membership Montgomery www.montgomeryzoo.com Montgomery Zoo card ARIZONA 50% off – 2 adults, 3 Prescott Heritage Park Zoo www.heritageparkzoo.org children Window Rock Navajo Nation Zoo Free www.navajozoo.org ARKANSAS Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% off www.littlerockzoo.com CALIFORNIA 50% off – per Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo www.charlespaddockzoo.org membership Free (2 adult/all children Bakersfield California Living Museum on member card, 10% www.calmzoo.org off gift shop Bonsall Wildwonders 50% off www.wildwonders.org 50% off – 2 adults, 2 Folsom Seaquest Interactive Aquarium www.folsom.visitseaquest.com children Free – 4 people; Julian California Wolf Center RESERVATIONS www.californiawolfcenter.org REQUIRED Lodi Micke Grove Zoo 50% off www.mgzoo.com Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% off www.lazoo.org Exotic Feline Breeding Free – 2 adults/3 Rosamond www.cathopuise.fcc.com Compound children San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% off www.sfzoo.org 50% off – 2 adults, 4 San Jose Happy Hollow Park & Zoo www.hhpz.org children, No Spec Events Free – 2 adults, 4 Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo www.santaanazoo.org children COLORADO 50% Off – 2 adults/2 Littleton Seaquest Littleton Littleton.visitseaquest.com children Pueblo Pueblo Zoo 50% off www.pueblozoo.org FLORIDA St. Augustine Alligator Farm St. Augustine 20% off www.alligatorfarm.com Zoological Park Tampa The Florida Aquarium 50% off www.flaquarium.org West Palm Beach Palm Beach Zoo 50% off www.palmbeachzoo.org IDAHO Idaho Falls Tautphaus Park Zoo 50% off www.idahofallsidaho.gov 2019 Reciprocal List (valid from 1.1.2019 – 12.31.2019) Free – 2 adults, 5 Pocatello Pocatello Zoo www.zoo.pocatello.us children ILLINOIS Free – 2 adults, 3 Springfield Henson Robinson Zoo children. -

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

Casa Del Prado in Balboa Park

Chapter 19 HISTORY OF THE CASA DEL PRADO IN BALBOA PARK Of buildings remaining from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, exhibit buildings north of El Prado in the agricultural section survived for many years. They were eventually absorbed by the San Diego Zoo. Buildings south of El Prado were gone by 1933, except for the New Mexico and Kansas Buildings. These survive today as the Balboa Park Club and the House of Italy. This left intact the Spanish-Colonial complex along El Prado, the main east-west avenue that separated north from south sections The Sacramento Valley Building, at the head of the Plaza de Panama in the approximate center of El Prado, was demolished in 1923 to make way for the Fine Arts Gallery. The Southern California Counties Building burned down in 1925. The San Joaquin Valley and the Kern-Tulare Counties Building, on the promenade south of the Plaza de Panama, were torn down in 1933. When the Science and Education and Home Economy buildings were razed in 1962, the only 1915 Exposition buildings on El Prado were the California Building and its annexes, the House of Charm, the House of Hospitality, the Botanical Building, the Electric Building, and the Food and Beverage Building. This paper will describe the ups and downs of the 1915 Varied Industries and Food Products Building (1935 Food and Beverage Building), today the Casa del Prado. When first conceived the Varied Industries and Food Products Building was called the Agriculture and Horticulture Building. The name was changed to conform to exhibits inside the building. -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS. -

APPLIED NUTRITIONAL STUDIES with ZOOLOGICAL REPTILES by KYLE SAMUEL THOMPSON Bachelor of Science in Animal Science California S

APPLIED NUTRITIONAL STUDIES WITH ZOOLOGICAL REPTILES By KYLE SAMUEL THOMPSON Bachelor of Science in Animal Science California State University Fresno Fresno, California 2006 Master of Science in Animal Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2016 APPLIED NUTRITIONAL STUDIED WITH ZOOLOGICAL REPTILES Dissertation Approved: Dr. Clint Krehbiel Dissertation Adviser Dr. Gerald Horn Dr. Scott Carter Dr. Lionel Dawson ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Until one has loved an animal, a part of one's soul remains unawakened." -Anatole France First and foremost, I would like to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. He has always provided a light for me during times of discouragement. Secondly I would like to give a very big thank you to my advisor and mentor Dr. Clint Krehbiel who has been very patient and caring all these years. Thank you for all the guidance and giving me the freedom to pursue my dreams. I also want to extend a thank you to Donna Perry, Diana Batson, and Debra Danley for always being there for me to comfort and laugh. I would like to send a special thank you to the San Diego Zoo Nutrition Services team, Dr. Mike Schlegel, Edith Galindo and Michele Gaffney. Thank you for your guidance and patience and continued friendship. Further thank you is needed to Dr. Schlegel for accepting me in 2009 and opening my eyes to the world of zoo and captive wildlife nutrition. -

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits List created by © birdsandbats on www.zoochat.com. Last Updated: 19/08/2019 African Clawless Otter (2 holders) Metro Richmond Zoo San Diego Zoo American Badger (34 holders) Alameda Park Zoo Amarillo Zoo America's Teaching Zoo Bear Den Zoo Big Bear Alpine Zoo Boulder Ridge Wild Animal Park British Columbia Wildlife Park California Living Museum DeYoung Family Zoo GarLyn Zoo Great Vancouver Zoo Henry Vilas Zoo High Desert Museum Hutchinson Zoo 1 Los Angeles Zoo & Botanical Gardens Northeastern Wisconsin Zoo & Adventure Park MacKensie Center Maryland Zoo in Baltimore Milwaukee County Zoo Niabi Zoo Northwest Trek Wildlife Park Pocatello Zoo Safari Niagara Saskatoon Forestry Farm and Zoo Shalom Wildlife Zoo Space Farms Zoo & Museum Special Memories Zoo The Living Desert Zoo & Gardens Timbavati Wildlife Park Turtle Bay Exploration Park Wildlife World Zoo & Aquarium Zollman Zoo American Marten (3 holders) Ecomuseum Zoo Salomonier Nature Park (atrata) ZooAmerica (2.1) 2 American Mink (10 holders) Bay Beach Wildlife Sanctuary Bear Den Zoo Georgia Sea Turtle Center Parc Safari San Antonio Zoo Sanders County Wildlife Conservation Center Shalom Wildlife Zoo Wild Wonders Wildlife Park Zoo in Forest Park and Education Center Zoo Montana Asian Small-clawed Otter (38 holders) Audubon Zoo Bright's Zoo Bronx Zoo Brookfield Zoo Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Dallas Zoo Denver Zoo Disney's Animal Kingdom Greensboro Science Center Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens 3 Kansas City Zoo Houston Zoo Indianapolis -

Aza Board & Staff

The Perfect Package. Quality, Value and Convenience! Order online! Discover what tens of thousands of customers — including commercial reptile breeding facilities, veterinarians, and some of our country’s most respected zoos www.RodentPro.com and aquariums — have already learned: with Rodentpro.com®, you get quality It’s quick, convenient AND value! Guaranteed. and guaranteed! RodentPro.com® offers only the highest quality frozen mice, rats, rabbits, P. O . Box 118 guinea pigs, chickens and quail at prices that are MORE than competitive. Inglefield, IN 47618-9998 We set the industry standards by offering unsurpassed quality, breeder Tel: 812.867.7598 direct pricing and year-round availability. Fax: 812.867.6058 ® With RodentPro.com , you’ll know you’re getting exactly what you order: E-mail: [email protected] clean nutritious feeders with exact sizing and superior quality. And with our exclusive shipping methods, your order arrives frozen, not thawed. We guarantee it. ©2013 Rodentpro.com,llc. PRESORTED STANDARD U.S. POSTAGE American Association of PAID Zoological Parks And Aquariums Rockville, Maryland PERMIT #4297 8403 Colesville Road, Suite 710 Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 (301) 562-0777 www.aza.org FORWARDING SERVICE REQUESTED MOVING? SEND OLD LABEL AND NEW ADDRESS DATED MATERIAL MUST BE RECEIVED BY THE 10TH CONNECT This Is Your Last Issue… Renew your AZA membership TODAY (see back panel for details) Connect with these valuable resources for Benefits Professional Associate, Professional Affiliate Available and Professional Fellow -

USS Midway Museum Historic Gaslamp Quarter Balboa Park

Approx. 22 Miles Approx. 28 Miles San Diego Zoo Del Mar Legoland Fairgrounds Safari Park Del Mar Beaches DOG FRIENDLY 56 North Beach 5 Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve Hiking Torrey Pines Golf Course 805 Torrey Pines Gliderport University of California San Diego Birch Aquarium at Scripps Westfield UTC Mall La Jolla Shores La Jolla Cove 52 Village of La Jolla SeaWorld USS Midway Historic Gaslamp Balboa Park & Museum Quarter San Diego Zoo Approx. 12 Miles Approx. 15 Miles Approx. 16 Miles Approx. 16 Miles Fun Things To Do Within Walking Distance Torrey Pines Golf Course (0.5 mi) – Perfect your swing at the world renowned Torrey Pines Golf Course, home to two 18-hole championship courses. This public course has a driving range and is open every day until 30 minutes before dusk. Call our Golf Team at 1-800-991-GOLF (4653) to book your tee time. Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve (0.8 mi) – Hike a trail in this beautiful 2,000-acre coastal state park overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Some trails lead directly to Torrey Pines State Beach. Trail maps available at our Concierge Desk. Torrey Pines Gliderport (1.5 mi) – Visit North America's top paragliding and hang gliding location and try an instructional tandem flight. Please call ahead since all flights are dependent on the wind conditions - (858) 452-9858. Fun Things To Do Just a Short Drive Away La Jolla Playhouse (2 mi) – A not-for-profit, professional theatre at the University of California San Diego. See Concierge for current showings. Birch Aquarium (3 mi) – Experience stunning sea life at Birch Aquarium at Scripps Institute of Oceanography. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contacts: Jennifer Zacharias, JZPR (805) 886-9078 or [email protected] SANTA BARBARA ZOO’S GIRAFFE & AMUR LEOPARD PREPARE TO DEPART AS PART OF CRITICAL SPECIES SURVIVAL PLAN Zoo will also welcome new Amur leopard and baby giraffes this spring (March 6, 2020) Santa Barbara, CA - T he Santa Barbara Zoo will soon bid farewell to Amirah, their almost two-year-old female Masai giraffe, and Wyatt, their seven-year-old male Amur leopard, as part of their ongoing work to support two of the A ssociation of Zoos and Aquariums ’s (AZA) Species Survival Plans. The Species Survival Plan (SSP) was developed in 1981 by the AZA to help ensure the survival of selected species in zoos and aquariums, many of which are threatened or endangered in the wild. Amirah, born at the Santa Barbara Zoo on March 14, 2018 to Audrey and Michael, will depart on March 10, 2020 (just shy of her second birthday) for the Sacramento Zoo . Giraffes typically become independent of their mothers around two years old and become mature enough to breed at three or four years old. "Over the last few months as we’ve prepared for her departure, we’ve really noticed her personality come alive, and she has become more independent and brave, trying new things without her mom nearby,” shared Cassie Moews, Senior Keeper. While she is still too young to breed right now, Amirah will have a breeding recommendation in the future. Amirah’s father Michael is the most genetically valuable Masai giraffe in the AZA North America population. -

Additional Member Benefits Reciprocity

Additional Member Benefits Columbus Member Advantage Offer Ends: December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted As a Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Member, you can now enjoy you can now enjoy Buy One, Get One Free admission to select Columbus museums and attractions through the Columbus Member Advantage program. No coupon is necessary. Simply show your valid Columbus Zoo Membership card each time you visit! Columbus Member Advantage partners for 2016 include: Columbus Museum of Art COSI Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens (Valid August 1 - October 31, 2016) King Arts Complex Ohio History Center & Ohio Village Wexner Center for the Arts Important Terms & Restrictions: Receive up to two free general admissions of equal or lesser value per visit when purchasing two regular-priced general admission tickets. Tickets must be purchased from the admissions area of the facility you are visiting. Cannot be combined with other discounts or offers. Not valid on prior purchases. No rain checks or refunds. Some restrictions may apply. Offer expires December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted. Nationwide Insurance As a Zoo member, you can save on your auto insurance with a special member-only discount from Nationwide. Find out how much you can save today by clicking here. Reciprocity Columbus Zoo Members Columbus Zoo members receive discounted admission to the AZA accredited Zoos in the list below. Columbus Zoo members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains their own discount policies, and the Columbus Zoo strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. -

The San Diego Zoo Safari Park

Welcome to the San Diego Zoo Safari Park Please note the Africa Tram is not included with school admission tickets. You must have purchased a separate Africa Tram ticket to experience this attraction. Here are a couple of tips to help you make the most of your day. Chaperones, please share these insider tips with your students. 1. Chaperones, please stay with your students at all times. The Safari Park is a large and exciting place and it is easy to get separated. Lost chaperones are brought to Ranger Base (indicated on reverse) to meet up with your students. 2. For best viewing of our animals, please use low voices, do not bang on the glass and try not to run. The animals will move away or hide from loud noise and fast movements. 3. If you want to feed our animals, please visit Lorikeet Landing (from 10:00 A.M. to 3:45 P.M. Lorikeet food is available for purchase, 10 students at a time), The other animals are on special diets and people food might make them sick. 4. If you want to pet our animals, please visit our Petting Kraal. Your teacher must schedule a visit time if you are visiting October 1st- 31st and May 11th - April 23rd. 5. Have a good time, take lots of pictures and ask questions. Safari Park staff are happy to assist. To further enhance your visit, you may want to see one of our shows or meet one of our animal ambassadors up close by seeing an Animal Encounter.