Categorified Reeb Graphs Arxiv:1501.04147V1 [Cs.CG]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Topology and Reeb Graph

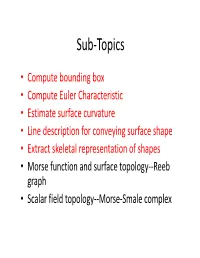

Sub-Topics • Compute bounding box • Compute Euler Characteristic • Estimate surface curvature • Line description for conveying surface shape • Extract skeletal representation of shapes • Morse function and surface topology--Reeb graph • Scalar field topology--Morse-Smale complex Surface Topology – Reeb Graph What is Topology? • Topology studies the connectedness of spaces • For us: how shapes/surfaces are connected What is Topology • The study of property of a shape that does not change under deformation – Rules of deformation • 1-1 and onto • Bicontinuous (continuous both ways) • Cannot tear, join, poke or seal holes – A is homeomorphic to B Why is Topology Important? • What is the boundary of an object? • Are there holes in the object? • Is the object hollow? • If the object is transformed in some way, are the changes continuous or abrupt? • Is the object bounded , or does it extend infinitely far? Why is Topology Important? • Inherent and basic properties of a shape • We want to accurately represent and preserve these properties in different applications – Surface reconstruction – Morphing – Texturing – Simplification – Compression Image source: http://www.utdallas.edu/~xxg06 1000/physicsmorphing.htm Topology-Basic Concepts • n-manifold – Set of points – Each point has a neighborhood homeomorphic to an open set of – An n-manifold is a topological space that “locally looks like” the Euclidian space Topology-Basic Concepts • Holes/genus – Genus of a surface is the maximal number of nonintersecting simple closed curves that can be cut on the surface without disconnecting it. • Boundaries Topology-Basic Concepts • Euler’s characteristic function – • #vertices, #edges, #faces – is independent of the polygonization – Specifically, 2 2 • What are c, g, and h? χ = 2 χ = 0 Topology-Basic Concepts • Orientability – Any surface has a triangulation – Orient all triangles CW or CCW – Orientability : any two triangles sharing an edge have opposite directions on that edge. -

Approximation of Metric Spaces by Reeb Graphs: Cycle Rank of A

Filomat xx (yyyy), zzz–zzz Published by Faculty of Sciences and Mathematics, DOI (will be added later) University of Niˇs, Serbia Available at: http://www.pmf.ni.ac.rs/filomat Approximation of Metric Spaces by Reeb Graphs: Cycle Rank of a Reeb Graph, the Co-rank of the Fundamental Group, and Large Components of Level Sets on Riemannian Manifolds Irina Gelbukh CIC, Instituto Polit´ecnico Nacional, 07738, Mexico City, Mexico Abstract. For a connected locally path-connected topological space X and a continuous function f on it such that its Reeb graph R f is a finite topological graph, we show that the cycle rank of R f , i.e., the first Betti number b1(R f ), in computational geometry called number of loops, is bounded from above by the co-rank of the fundamental group π1(X), the condition of local path-connectedness being important since generally b1(R f ) can even exceed b1(X). We give some practical methods for calculating the co-rank of π1(X) and a closely related value, the isotropy index. We apply our bound to improve upper bounds on the distortion of the Reeb quotient map, and thus on the Gromov-Hausdorff approximation of the space by Reeb graphs, for the distance function on a compact geodesic space and for a simple Morse function on a closed Riemannian manifold. This distortion is bounded from below by what we call the Reeb width b(M) of a metric space M, which guarantees that any real-valued continuous function on M has large enough contour (connected component of a level set). -

The Reeb Graph Edit Distance Is Universal

The Reeb Graph Edit Distance Is Universal Ulrich Bauer Department of Mathematics, Technical University of Munich (TUM), Germany [email protected] Claudia Landi Dipartimento di Scienze e Metodi dell’Ingegneria, Università degli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy [email protected] Facundo Mémoli Department of Mathematics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA [email protected] Abstract We consider the setting of Reeb graphs of piecewise linear functions and study distances between them that are stable, meaning that functions which are similar in the supremum norm ought to have similar Reeb graphs. We define an edit distance for Reeb graphs and prove that it is stable and universal, meaning that it provides an upper bound to any other stable distance. In contrast, via a specific construction, we show that the interleaving distance and the functional distortion distance on Reeb graphs are not universal. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Theory of computation → Computational geometry; Mathematics of computing → Algebraic topology Keywords and phrases Reeb graphs, topological descriptors, edit distance, interleaving distance Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/LIPIcs.SoCG.2020.15 Funding This research has been partially supported by FAR 2014 (UniMORE), ARCES (University of Bologna), and the DFG Collaborative Research Center SFB/TRR 109 “Discretization in Geometry and Dynamics”. Acknowledgements We thank Barbara Di Fabio and Yusu Wang for valuable discussions. 1 Introduction The concept of a Reeb graph of a Morse function first appeared in [13] and has subsequently been applied to problems in shape analysis in [14, 10]. The literature on Reeb graphs in the computational geometry and computational topology is ever growing (see, e.g., [2, 3] for a discussion and references). -

Realizable Piecewise Linear Paths of Persistence Diagrams with Reeb Graphs

Realizable piecewise linear paths of persistence diagrams with Reeb graphs Rehab Alharbi1, Erin Wolf Chambers2, and Elizabeth Munch2 1Dept of Mathematics & Statistics, Saint Louis University 2Dept of Computer Science, Saint Louis University 3Dept of Computational Mathematics, Science & Engineering, Dept of Mathematics, Michigan State University Abstract Reeb graphs are widely used in a range of fields for the purposes of analyzing and com- paring complex spaces via a simpler combinatorial object. Further, they are closely related to extended persistence diagrams, which largely but not completely encode the information of the Reeb graph. In this paper, we investigate the effect on the persistence diagram of a particular continuous operation on Reeb graphs; namely the (truncated) smoothing operation. This con- struction arises in the context of the Reeb graph interleaving distance, but separately from that viewpoint provides a simplification of the Reeb graph which continuously shrinks small loops. We then use this characterization to initiate the study of inverse problems for Reeb graphs using smoothing by showing which paths in persistence diagram space (commonly known as vineyards) can be realized by a path in the space of Reeb graphs via these simple operations. This allows us to solve the inverse problem on a certain family of piecewise linear vineyards when fixing an initial Reeb graph. 1 Introduction Reeb graphs have become an important tool in topological data analysis for the purpose of visualiz- ing continuous functions on complex spaces, as they yield a simplified discrete structure. Originally developed in relation to Morse theory [29], these objects are used extensively for shape comparison, constructing skeletons of data sets, surface simplification, and visualization; for more details on arXiv:2107.04654v1 [cs.CG] 9 Jul 2021 these and more applications, we refer to recent surveys on the topic [5, 31]. -

Thermodynamic Tree: the Space of Admissible Paths † Alexander N

SIAM J. APPLIED DYNAMICAL SYSTEMS c 2013 Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 246–278 ∗ Thermodynamic Tree: The Space of Admissible Paths † Alexander N. Gorban Abstract. Is a spontaneous transition from a state x to a state y allowed by thermodynamics? Such a question arises often in chemical thermodynamics and kinetics. We ask the following more formal question: Is there a continuous path between these states, along which the conservation laws hold, the concentra- tions remain nonnegative, and the relevant thermodynamic potential G (Gibbs energy, for example) monotonically decreases? The obvious necessary condition, G(x) ≥ G(y), is not sufficient, and we construct the necessary and sufficient conditions. For example, it is impossible to overstep the equi- − librium in 1-dimensional (1D) systems (with n components and n 1 conservation laws). The system cannot come from a state x to a state y if they are on the opposite sides of the equilibrium even if G(x) >G(y). We find the general multidimensional analogue of this 1D rule and constructively solve the problem of the thermodynamically admissible transitions. We study dynamical systems, which are given in a positively invariant convex polyhedron D and have a convex Lyapunov function G. An admissible path is a continuous curve in D along which G does not increase. For x, y ∈ D, x y (x precedes y) if there exists an admissible path from x to y and x ∼ y if x y and y x. ThetreeofG in D is a quotient space D/ ∼ . We provide an algorithm for the construction of this tree. -

Introduction to Topological Data Analysis Julien Tierny

Introduction to Topological Data Analysis Julien Tierny To cite this version: Julien Tierny. Introduction to Topological Data Analysis. Doctoral. France. 2017. cel-01581941 HAL Id: cel-01581941 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/cel-01581941 Submitted on 5 Sep 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06 Laboratoire d’Informatique de Paris 6 Julien Tierny Introduction to Topological Data Analysis Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06 Laboratoire d’Informatique de Paris 6 UMR UPMC/CNRS 7606 – Tour 26 4 Place Jussieu – 75252 Paris Cedex 05 – France Notations X Topological space ¶X Boundary of a topological space M Manifold Rd Euclidean space of dimension d s, t d-simplex, face of a d-simplex v, e, t, T Vertex, edge, triangle and tetrahedron Lk(s), St(s) Link and star of a simplex Lkd(s), Std(s) d-simplices of the link and the star of a simplex K Simplicial complex T Triangulation M Piecewise linear manifold bi i-th Betti number c Euler characteristic th ai i barycentric coordinates of a point p relatively -

Time-Varying Reeb Graphs: a Topological Framework Supporting the Analysis of Continuous Time-Varying Data

Time-varying Reeb Graphs: A Topological Framework Supporting the Analysis of Continuous Time-varying Data by Ajith Arthur Mascarenhas A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Computer Science. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: Jack Snoeyink, Advisor Herbert Edelsbrunner, Reader Valerio Pascucci, Reader Dinesh Manocha, Committee Member Leonard McMillan, Committee Member ii iii c 2006 Ajith Arthur Mascarenhas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iv v ABSTRACT AJITH ARTHUR MASCARENHAS: Time-varying Reeb Graphs: A Topological Framework Supporting the Analysis of Continuous Time-varying Data. (Under the direction of Jack Snoeyink.) I present time-varying Reeb graphs as a topological framework to support the anal- ysis of continuous time-varying data. Such data is captured in many studies, including computational uid dynamics, oceanography, medical imaging, and climate modeling, by measuring physical processes over time, or by modeling and simulating them on a computer. Analysis tools are applied to these data sets by scientists and engineers who seek to understand the underlying physical processes. A popular tool for analyzing scienti¯c datasets is level sets, which are the points in space with a ¯xed data value s. Displaying level sets allows the user to study their geometry, their topological features such as connected components, handles, and voids, and to study the evolution of these features for varying s. For static data, the Reeb graph encodes the evolution of topological features and compactly represents topological information of all level sets. -

Introduction to Reeb Graphs and Contour Trees

Introduction to Reeb Graphs and Contour Trees Lecture 15 Scribed by: ABHISEK KUNDU Sometimes we are interested in the topology of smooth functions as a means to analyze and visualize intrinsic properties of geometric models and scientific data. Creation and destruction of components of the level set could be an important visual technique for this purpose. Reeb graphs are obtained by contracting the connected components of the level sets to points. They could be useful visual analytical tool because they express the connectivity of level sets. DEFINITION: ( Level Set ) A level set of a real-valued function f of n variables is a set of the form: { (X1,...,Xn) | f (X1,...,Xn) = c} where c is a constant. In other words, it is the set where the function takes on a given constant value. When the number of variables is two, this is a level curve or contour line, if it is three a level surface, and for higher values of n the level set is a level hypersurface. Sublevel set: of f is a set of the form { (X1,...,Xn) | f (X1,...,Xn) ≤ c} Contour: at a given value c, contour is the connected component of level set Xc [Figure 1] Equivalence of points: two points x and y are equivalent if they belong to the same contour of Xc for some given constant c. [Figure 1] Quotient topology and space: Let us denote ~ to be an equivalence relation defined on a topological space X. e be the set of equivalence classes and let ψ : map each point x to its equivalence class DEFINITION: Quotient topology of consists of all subsets U belonging t whose preimages, ψ -1 (U), are open in X. -

Reeb Graphs: Approximation and Persistence

Reeb Graphs: Approximation and Persistence Tamal K. Dey∗ Yusu Wang∗ Abstract Given a continuous function f : X → IR on a topological space X, its level set f −1(a) changes continuously as the real value a changes. Consequently, the connected components in the level sets appear, disappear, split and merge. The Reeb graph of f summarizes this information into a graph structure. Previous work on Reeb graph mainly focused on its efficient computation. In this paper, we initiate the study of two important aspects of the Reeb graph which can facilitate its broader applications in shape and data analysis. The first one is the approximation of the Reeb graph of a function on a smooth compact manifold M without boundary. The approximation is computed from a set of points P sampled from M. By leveraging a relation between the Reeb graph and the so-called vertical homology group, as well as between cycles in M and in a Rips complex constructed from P , we compute the H1-homology of the Reeb graph from P . It takes O(n log n) expected time, where n is the size of the 2-skeleton of the Rips complex. As a by-product, when M is an orientable 2-manifold, we also obtain an efficient near-linear time (expected) algorithm for computing the rank of H1(M) from point data. The best known previous algorithm for this problem takes O(n3) time for point data. The second aspect concerns the definition and computation of the persistent Reeb graph homology for a sequence of Reeb graphs defined on a filtered space. -

Analyzing Data with 1D Non-Linear Shapes Using Topological Methods

Analyzing data with 1D non-linear shapes using topological methods Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Suyi Wang, M.S. Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Yusu Wang, Advisor Rephael Wenger Tamal K. Dey c Copyright by Suyi Wang 2018 Abstract Shape analysis has been applied in many applications across a broad range of domains. Among various different families of \complex" shapes, the ones with 1D non- linear topological structures (skeletons) are particularly interesting. These shapes are simple, as they can be decomposed into 1-d pieces, but still informative in representing the connectivity and other important information behind data. In this thesis, I focus on two objects from computational topology that have been useful for modeling the skeleton of data: the Reeb graph (and its variants) and the 1-(un)stable manifold from discrete Morse theory, and study their properties as well as applications to shape analysis. The two specific topological objects that I focus on have both already been widely used in practical applications. Further theoretical understanding and applications of these two objects in modeling and studying the skeleton of data will be provided. The first part of the dissertation work concerns the so-called Reeb graph and its loop-free variant, the contour tree, which can be used to provide a 1D tree summary of an input scalar field. It has been commonly used in computer graphics and visual- ization. I have investigated one problem regarding to the theoretical understanding of the contour tree, as well as developing a variant of the Reeb graph to address the issue of noise. -

Time-Varying Reeb Graphs: a Topological Framework Supporting the Analysis of Continuous Time-Varying Data

UCRL-TH-226559 Time-varying Reeb Graphs: A Topological Framework Supporting the Analysis of Continuous Time-varying Data A. Mascarenhas December 6, 2006 Disclaimer This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor the University of California nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or the University of California, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by University of California, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract W-7405-Eng-48. UCRL-TH-226559 Time-varying Reeb Graphs: A Topological Framework Supporting the Analysis of Continuous Time-varying Data by Ajith Arthur Mascarenhas A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial ful¯llment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Computer Science. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: Jack Snoeyink, Advisor Herbert Edelsbrunner, Reader Valerio Pascucci, Reader Dinesh Manocha, Committee Member Leonard McMillan, Committee Member ii iii c 2006 Ajith Arthur Mascarenhas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iv v ABSTRACT AJITH ARTHUR MASCARENHAS: Time-varying Reeb Graphs: A Topological Framework Supporting the Analysis of Continuous Time-varying Data. -

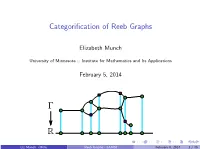

Categorification of Reeb Graphs

Categorification of Reeb Graphs Elizabeth Munch University of Minnesota :: Institute for Mathematics and Its Applications February 5, 2014 Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 1 / 46 What's the plan? Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 2 / 46 What's the plan? Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 2 / 46 What's the plan? Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 2 / 46 Original Reeb Graph construction Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 3 / 46 Original Reeb Graph construction Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 3 / 46 Original Reeb Graph Definition Definition Given topological space X with a function f : X ! R, say x ∼ y if x and y are in the same connected component of f −1(a). The Reeb graph of the function f is the space X= ∼ with the quotient topology. Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 4 / 46 Morse Function Setting Let f be Morse with distinct critical values. critical values , Nodes Index of critical values , Type of node I Min/max , Deg 1 vertex I Saddle , Deg 3 vertex Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 5 / 46 Applications Handle removal, from Wood 3D shape matching, from et al, 2002 Hilaga et.al, 2001 Basis for homology groups, Shape skeletonization, from Dey et. al, 2013 from Biasotti et.al, 2008 Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 6 / 46 Smoothing Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 7 / 46 Smoothing Liz Munch (IMA) Reeb Graphs - SAMSI February 5, 2014 7 / 46 Other work Functional distortion distance [Bauer Ge Wang 2013] Topological simplification [Doraiswamy Natarajan 2012], [Ge et at 2011], [Pascucci et al 2007] Smoothing Goals Give a metric to compare Reeb graphs.