Erev Rosh Hashanah 5779: Lost and Found

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B'nai Moshe Israel Adventure

B’nai Moshe Israel Adventure October 27-November 7, 2019 Led by Rabbi Shalom Kantor updated August 21 Sunday, October 27: DEPARTURE . Depart from Detroit Monday, October 28: BRUCHIM HABA’IM – WELCOME! . Arrival in Israel; meet and greet service at the airport . Meet your guide and travel to Tel Aviv; check into your hotel and freshen up . Welcome to Israel ceremony overlooking the Tel Aviv shoreline . Welcome dinner at a local restaurant Overnight: David InterContinental Hotel, Tel Aviv Tuesday, October 29: ISRAEL AT 70 . Explore just how far Israel has come since its inception with a look at the Startup Nation at the Taglit Innovation Center . Site visit to Save A Child's Heart whose mission is to improve the quality of pediatric cardiac care for children from developing countries who suffer from heart disease and who cannot get adequate medical care in their home countries. Run Activities and play with children that are waiting for or recovering from surgery . Delve into modern Hebrew culture and learn Hebrew on the way on a graffiti tour of Southern Tel Aviv . Enjoy the crafts and the street performers at the renowned Nahalat Binyamin Arts and Crafts Fair and the adjacent Carmel Market . Dinner at trendy Deca Restaurant Overnight: David InterContinental Hotel, Tel Aviv Wednesday, October 30: GOING DOWN . In Sderot – the town (in)famous for being the target of Hamas rockets, tour the town, see the collection of katyusha rockets which landed in the area and see how they protect their residents; understand why it is so difficult to find an apartment available for rent or purchase . -

Masorti in Jerusalem Can the Movement Maintain a Stronghold in the Holy City?

JANUARY 10, 2019 Masorti in Jerusalem Can the movement maintain a stronghold in the Holy City? Bs”d s ervice sealing Bereshit • Roof sealing and coatings Buying and selling • Sealing exterior walls בראשִ ית home upholstering איטום ושיקום renovation and styling • Waterproofng of basements Call now מורשה מכון התקנים Abseiling services • Tel. 052-3936376 ∙ 14 Yad Harutzim, SEE ON PAGE 16 at the Dafna and & Vera passageway 052-434-5299 COVER DR. YIZHAR HESS, CEO of the Masorti Movement in Israel, at a Masorti protest. The front sign reads, ‘Judaism without coercion,’ while the back Jerusalem's Masorti Movement: quotes the Torah principle to ‘Love your fellow as yourself.’ Fading future? • ALAN ROSENBAUM he Masorti Movement in Israel,” says Rabbi Peretz Rodman, Jerusalem-based author and ‘Thead of the Masorti rabbinic court of Israel, “was established by the wave of North American im- migrants – many of whom were rabbis and Jewish ed- ucators – who came in the wake of the Six Day War. They came in 1969, 1970 and 1971, and wanted to cre- ate their own institutions.” More than 50 years later, as the generation of Con- servative Jews that arrived full of post-1967 Zionist ardor passes from the scene, some of Jerusalem’s Masorti synagogues are shrinking. Is a new genera- tion of Masorti Jews ready to take their place, or is Conservative Judaism in Jerusalem destined to fall to the growing haredi influence in the city? Dr. Yizhar Hess, CEO of the Masorti Movement in Israel, is convinced that Masorti Judaism has a future in Israel’s capital, despite its image as a growing bas- tion of ultra-Orthodoxy. -

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem

Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) P.O Box 860, Caritas Street – Bethlehem, Phone: (+972) 2 2741889, Fax: (+972) 2 2776966. [email protected] | http://www.arij.org Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Report on the Israeli Colonization Activities in the West Bank & the Gaza Strip Volume 183, October 2013 Issue http://www.arij.org Bethlehem • Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) stormed and searched several Palestinian houses in At-Tal area in Al-Khader village, west of Bethlehem city. Clashes erupted between Palestinians and the IOA, the IOA fired teargas and stun grenades at Palestinians, causing dozens of suffocation cases. (Maannews 2 October 2013) • Due to the high demand for residential around the Gush Etzion settlement bloc, headed by David Pearl held last week a community event marketing character Orthodox community located east of Gush Etzion and overlooking the breathtaking views of the Judean Desert and Sea - Dead Sea. Event marketing, hundreds of interested and family traveled Regional Council organized rides and departing Jerusalem, Beit Shemesh and Beitar Illit, in addition to the many guests who independently. Guests were impressed by the houses planned program and many of them were continuing process of reception and purchase, while their children enjoyed Fanning particularly experienced and workshops that included inflatable baking clay and makeup design. Shunt community now numbers 55 religious families and community will soon begin construction of private homes. In the first stage, which should start in the coming weeks will be built 60 units, when the entire final project will include 300 residential units. Gush Etzion Council noted that the past year has been a leader in the Regional Council population growth stood at 4.1%, and the regional council expect to double this number in the coming years. -

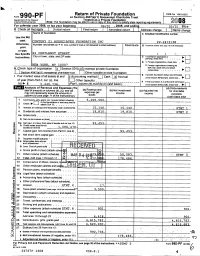

Return of Private Foundation

hilis, Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form• 990-PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust I 008 Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2008, or tax year beg inning 06 / 01 r 2008 , and ending 05 / 31 , 2009 G Check all that apply initial return Final return Amended return T_Address chance I Nama rh..,.,o Name of foundation A Employer Identification number Use the IRS label. CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 Otherwise , Number and street ( or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ( see page 10 of to vebucbore) print or type. See Specific 22 CORTLANDT STREET _ Instructions . City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here • • . D 1. Foreign organizations , check here , NEW YORK , NY 10007 2. Foreign organizations meeting the co ones . here and attach H Check type of organization. X Section 501 ( c 3 lucom exempt private foundation cam p utation Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method : Cash X] Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A) , check here . 0. El of year (from Part ll, col. (c), line Other (specify) _ _ _ _ __________________ F If the foundation Is in afi0-monthtermination 16) ' $ 5 , 440 , 73 6. -

Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2013

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2013 Maya Choshen Michal Korach Inbal Doron Yael Israeli Yair Assaf-Shapira 2013 Publication Number 427 Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2013 Maya Choshen, Michal Korach, Inbal Doron, Yael Israeli, Yair Assaf-Shapira © 2013, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem http://www.jiis.org Table of Contents About the authors .......................................................................................................... 5 Preface ............................................................................................................................. 6 Area ................................................................................................................................. 7 Population ....................................................................................................................... 7 Population size .................................................................................................................. 7 Geographic distribution of the population ........................................................................ 9 Population growth ............................................................................................................. 9 Age of the population ...................................................................................................... 10 Sources of Population Growth ................................................................................... -

Tel Aviv, Known As the “City That Never Sleeps,” with Its Centres of Culture, Recreation and National History, and Great Beaches

ITINERARY D a y O n e : Saturday, December 22, 2018 DEPARTURE ▪ Group flights: ▪ 9:00 p.m. Depart from Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) on El Al flight #026 arriving to Ben Gurion International Airport at 2:20pm on December 23. ▪ 11:50 p.m. Depart from John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) on El Al flight #008 arriving to Ben Gurion International Airport at 5:10pm on December 23. Overnight: Flight D a y T w o : Sunday, December 23, 2018 WELCOME TO ISRAEL ▪ Arrive at Ben Gurion International Airport. ▪ Welcome by our representative and assistance with arrival formalities. ▪ Group transfers to the city of Tel Aviv, known as the “city that never sleeps,” with its centres of culture, recreation and national history, and great beaches. ▪ Check into the hotel. ▪ 7:45 p.m. Meet next to the da’at hospitality desk at the hotel. ▪ 8:00 p.m. Depart the hotel. ▪ Welcome dinner at Meatos, known for its excellent meat dishes, including an orientation with PAS staff, track chairs and your tour educators. Overnight: Hilton, Tel Aviv D a y T h r e e : Monday, December 24, 2018 FOUNDATIONS OF A CITY AND A STATE ▪ Optional Minyan. ▪ Morning moment. PAS EVENT WELCOME TO ISRAEL @ 70! Begin the trip together as a community with a special ISRAELI BREAKFAST EVENT with opening remarks and greetings from your Rabbis and trip leaders. ▪ 10:00 a.m. Israel at 70 – Reviving the Hebrew Language: dialogue with Gil Hovav, a leading culinary journalists and television personality and the great-grandson of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the reviver of the Hebrew language. -

12,065. O. 0. Total Operating and Administrative Expenses Add Lines 13 Through 23 I 25 12 451

,Lim 99g,pF Return of Private Foundation OMB N51545-0052 1 or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Tremury i11i.111ai Revenue service Note The foundation may be ableTreated to use a copy of this returnas to asatisfy Private state reporting requirements. Foundation Forcalendaryear2009, or tax year beginning ,and ending G Check all that apply: LJ Initial return M Initial return ofa former public charity M Final return lj Amended return E Address change 1:1 Name change Use the IRS Name of foundation A Employer identification number label. Othenrrise, HEHEBAR FAMILY FOUNDATION INC. 13-3178015 prim Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Ftoom/suite B Telephone number "IWW 1000 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE (718) 485-3000 SeeInstructions. Specmc CITY Of IOWII, S1316, and ZIP C006 C If exemption application is pending, check here Foreign organizations, check here PQ H Check typeROOKLYN, of organization: l.X-I Section NY 501(c)(3) 11207-8417 exempt private foundation pl " Foreigncheck organizations here and meeting attach the 85% computation test, lj Section 4947(a)( 1) nonexempt charitable trust Z Othertaxable private foundation E H private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value ofall assets at end of year J Accounting method: M Cash DLI Accrual u nder section 507(b)(1)(A), check here P13 (from Parr//, co/ (C), /me 16) D Other (specify) F 11 the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 9 U 9 2 3 I 5 6 7 , (Part I, column (d) must be on cash bas/s ) Under section 507(b)(1)(B),d checkD b here t plz Paf-1 I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net mvestmem rciediustedne 1.1 .I.:f..c:e:23. -

Affinity Excursions …Enlightened Travel

Affinity Excursions...enlightened travel Somerset, Hunterdon and Warren County Jewish Federations Fall Trip to Israel Oct 29-Nov 7, 2016 Day 1, Sat Oct 29, 2016 – Departure for Tel Aviv Depart Newark Airport on flight LY026 at 11.30pm to Tel Aviv. Dinner and overnight en route Day 2, Sun Oct 30, 2016 Arrive to Israel 4.05pm: Arrival in Israel – Bruchim Haba’im. After completing arrival proceedings meet your guide and driver and proceed to Tel Aviv 6.00pm: Shehecheyanu + welcome cocktail from Jaffa/Tel Aviv vantage point 7.00pm: Check-in hotel 8. 00pm: Dinner + Speaker: Beyond the Headlines: Context and Perspectives on Israel Overnight: Royal Beach Hotel, Tel Aviv Day 3, Mon Oct 31, 2016 Vibrant Tel Aviv Enjoy a sumptuous buffet breakfast to begin your day. 9.00am: Depart the hotel for a walking tour of Tel Aviv’s development. Explore the first neighborhoods built beyond Jaffa that highlight Tel Aviv’s reputation for innovation and creativity. We will also walk in the Florentine neighborhood with an installation artist to learn what makes one an Israeli. 12.00pm: Depart for Beit Halochem where we enjoy lunch and activities with FIDV. 3.00pm: Rabin Museum: See Israel’s development through the life and times of Yitzchak Rabin. His daughter, Dalia Rabin, has been invited to meet with the group. 5.00pm: Return to hotel. Dinner together Overnight: Royal Beach Hotel, Tel Aviv Day 4, Tues Nov 1, 2016 Negba - Building the Land and the People of the Negev Enjoy a sumptuous buffet breakfast to begin your day. -

Torah and Do More Mitzvahs Suffering from His Marriage

The Jewish National Edition Post &Opinion Presenting a broad spectrum of Jewish News and Opinions since 1935. Volume 81, Number 1 • November 19, 2014 • 26 Chesvan 5775 www.jewishpostopinion.com • www.ulib.iupui.edu/digitalscholarship/collections/JPO HappyHappy ChanukahChanukah Cover art by Eduard Gurevich. © Eduard Gurevich 2003 See About the Cover, p.2. (see full painting on p. 20) 2 The Jewish Post & Opinion – NAT November 19, 2014 Editorial About the Cover Inside this Issue Hanukkiah in old synagogue, Mea Shearim The following excerpts are from my By Eduard Gurevich Editorial.....................................................2 editorials from our past two Indiana About the Cover ......................................2 editions. In this issue, we also have two This artwork is oil on canvas and was Rabbi Benzion Cohen columns each from those editions by my done in memory of his parents, Lucy (Chassidic Rabbi).....................................3 brother, Rabbi Benzion Cohen, and Yiddish Givertsman and Mikhael Gurevich and Kidney still needed for Drew...............3 columnist Henya Chaiet. his uncle and teacher Henya Chaiet Max Malovitsky. They (Yiddish for Everyday) ............................4 In my brother’s column on page 3, he fought against the Nazis Ted Roberts writes that love is one of the ways to bring in the Red Army, but his (Spoonful of Humor) ...............................5 peace to the world. I agree and add that other relatives were killed Rabbi Sandy E. Sasso .............................5 music is also a powerful method. by the Nazis. Rabbi Irwin Wiener, D.D. When The Yuval Ron Ensemble was in Eduard Gurevich was (Wiener’s Wisdom)..................................6 Indianapolis for International Peace Day born in Dnepropetrovsk, E. -

Political and Religious Consequences

Archaeological Activity in the Old City: Political and Religious Consequences 2015 December 2015 Written by: Yonathan Mizrachi Research: Gideon Suleimani Translation: Dana Hercbergs, Jessica Bonn Proof-editing: Talya Ezrahi Graphic Design and Maps: Lior Cohen Photographs: Yael Ilan and Emek Shaveh Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an organization of archaeologists and heritage professionals focusing on the role of tangible cultural heritage in Israeli society and in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We view archaeology as a resource for strengthening understanding between different peoples and cultures. This publication was produced by Emek Shaveh (A public benefit corporation) with the support of the Norwegian Embassy in Israel, the Federal Department for Foreign Affairs Switzerland (FDFA), Irish Foreign Ministry, CCFD and Cordaid. Responsibility for the information contained in this report belongs exclusively to Emek Shaveh. This information does not represent the opinions of the abovementioned donors. Table of contents Introduction 5 Major Influential Bodies 6 The Western Wall Heritage Foundation at the Western Wall plaza and tunnels 8 Davidson Center – Divided Between Women of the Wall and the Elad Foundation 12 Elad Foundation and the Nature and Parks Authority in Silwan Village 16 The Nature and Parks Authority in the Bab al-Rahma Cemetery 20 Israeli Activity and Influence on the Temple Mount / Haram al-Sharif 22 Palestinian Activity in Jerusalem 23 The International Community 25 Summary and Conclusions: Antiquities Caught between Political and Religious Struggles in the Old City 27 Map 1 Introduction In recent years ancient sites in Jerusalem have become part of the general political and religious struggle around holy sites, particularly in the areas surrounding the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif. -

Let My People Know Limmud FSU: the Story of Its First Decade

Let My People Know Limmud FSU: The Story of its First Decade LET MY PEOPLE KNOW Limmud FSU: The Story of its First Decade Mordechai Haimovitch Translated and Edited by Asher Weill Limmud FSU New York/Jerusalem Copyright@Limmud FSU International Foundation, New York, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form without the prior permission of the copyright holder Editor’s Notes. Many place names in this book are interchangeable because of the various stages of historical or political control. We have usually chosen to use the spellings associated with Jewish history: eg. Kiev not Kviv; Lvov not Lviv; Kishinev not Chișinău; Vilna not Vilnius, etc. Every attempt had been made to trace the source of the photographs in the book. Any corrections received will be made in future editions. Limmud FSU International Foundation 80, Central Park West New York, NY 10023 www.Limmudfsu.org This book has been published and produced by Weill Publishers, Jerusalem, on behalf of Limmud FSU International Foundation. ISBN 978-965-7405-03-1 Designed and printed by Yuval Tal, Ltd., Jerusalem Printed in Israel, 2019 CONTENTS Foreword - Natan Sharansky 9 Introduction 13 PART ONE: BACK IN THE USSR 1. A Spark is Kindled 21 2. Moscow: Eight Years On 43 3. The Volunteering Spirit 48 4. The Russians Jews Take Off 56 5. Keeping Faith in the Gulag 62 6. Cosmonauts Over the Skies of Beersheba 66 7. The Tsarina of a Cosmetics Empire 70 PART TWO: PART ONE: BACK IN THE USSR 8. -

Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation and Temple Beth El Trip to Israel

Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation and Temple Beth El Trip to Israel Led by Rabbi Brett Krichiver and Mark Miller December 23, 2018- January 2, 2019 Proposed by Makor Educational Journeys Sunday, December 23, 2018 Depart USA Overnight: In Flight Day 1: Monday, December 24, 2018 Note: The first day’s itinerary will be subject to change depending on when the flight arrives BRUCHIM HABAIM - WELCOME! Arrive at Ben Gurion International Airport, with assistance by a Makor Educational Journeys representative Meal en route TBA Check in to the hotel Dinner at the hotel Overnight: Kibbutz HaGoshrim Guesthouse, Galilee Day 2: Tuesday, December 25, 2018 OF MYSTICISM AND MOTHER NATURE Breakfast at the hotel Travel to the restored Agamon Hula Nature Reserve and ride golf carts or bicycles through the Hula Wetlands, an important resting place for migrating birds, which fly over Israel on their way to/from Europe and Africa Drive to Tzfat to explore the synagogues of the mystics, set along the alleyways with shops selling Judaica and art galleries Glassblowing demonstration with Sheva Chaya, an artist inspired by Kabbalah Visit the Safed Candle Factory and make Shabbat or Havdallah candles Street lunch on own in the Old City of Tzfat Activity with Livnot u’Lehibanot, one of the veteran Israeli programs established to strengthen Jewish identity Dinner at the hotel Overnight: Kibbutz HaGoshrim Guesthouse, Galilee Day 3: Wednesday, December 26, 2018 NORTHERN EXPOSURES Breakfast at the hotel Option: Proceed to the Western Galilee Partnership