The Kidneys in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PATHOLOGY of the RENAL SYSTEM”, I Hope You Guys Like It

ﺑﺴﻢ اﷲ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﻦ اﻟﺮﺣﯿﻢ ھﺬه اﻟﻤﺬﻛﺮة ﻋﺒﺎرة ﻋﻦ إﻋﺎدة ﺗﻨﺴﯿﻖ وإﺿﺎﻓﺔ ﻧﻮﺗﺎت وﻣﻮاﺿﯿﻊ ﻟﻤﺬﻛﺮة زﻣﻼﺋﻨﺎ ﻣﻦ اﻟﺪﻓﻌﺔ اﻟﺴﺎﺑﻘﺔ ٤٢٧ اﻷﻋﺰاء.. ﻟﺘﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻣﻊ اﻟﻤﻨﮭﺞ اﻟﻤﻘﺮر ﻣﻦ اﻟﻘﺴﻢ ﺣﺮﺻﻨﺎ ﻓﯿﮭﺎ ﻋﻠﻰ إﻋﺎدة ﺻﯿﺎﻏﺔ ﻛﺜﯿﺮ ﻣﻦ اﻟﺠﻤﻞ ﻟﺘﻜﻮن ﺳﮭﻠﺔ اﻟﻔﮭﻢ وﺳﻠﺴﺔ إن ﺷﺎء اﷲ.. وﺿﻔﻨﺎ ﺑﻌﺾ اﻟﻨﻮﺗﺎت اﻟﻤﮭﻤﺔ وأﺿﻔﻨﺎ ﻣﻮاﺿﯿﻊ ﻣﻮﺟﻮدة ﺑﺎﻟـ curriculum ﺗﻌﺪﯾﻞ ٤٢٨ ﻋﻠﻰ اﻟﻤﺬﻛﺮة ﺑﻮاﺳﻄﺔ اﺧﻮاﻧﻜﻢ: ﻓﺎرس اﻟﻌﺒﺪي ﺑﻼل ﻣﺮوة ﻣﺤﻤﺪ اﻟﺼﻮﯾﺎن أﺣﻤﺪ اﻟﺴﯿﺪ ﺣﺴﻦ اﻟﻌﻨﺰي ﻧﺘﻤﻨﻰ ﻣﻨﮭﺎ اﻟﻔﺎﺋﺪة ﻗﺪر اﻟﻤﺴﺘﻄﺎع، وﻻ ﺗﻨﺴﻮﻧﺎ ﻣﻦ دﻋﻮاﺗﻜﻢ ! 2 After hours, or maybe days, of working hard, WE “THE PATHOLOGY TEAM” are proud to present “PATHOLOGY OF THE RENAL SYSTEM”, I hope you guys like it . Plz give us your prayers. Credits: 1st part = written by Assem “ THe AWesOme” KAlAnTAn revised by A.Z.K 2nd part = written by TMA revised by A.Z.K د.ﺧﺎﻟﺪ اﻟﻘﺮﻧﻲ 3rd part = written by Abo Malik revised by 4th part = written by A.Z.K revised by Assem “ THe AWesOme” KAlAnTAn 5th part = written by The Dude revised by TMA figures were provided by A.Z.K Page styling and figure embedding by: If u find any error, or u want to share any idea then plz, feel free to msg me [email protected] 3 Table of Contents Topic page THE NEPHROTIC SYNDROME 4 Minimal Change Disease 5 MEMBRANOUS GLOMERULONEPHRITIS 7 FOCAL SEGMENTAL GLOMERULOSCLEROSIS 9 MEMBRANOPROLIFERATIVE GLOMERULONEPHRITIS 11 DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY (new) 14 NEPHRITIC SYNDROME 18 Acute Post-infectious GN 19 IgA Nephropathy (Berger Disease) 20 Crescentic GN 22 Chronic GN 24 SLE Nephropathy (new) 26 Allograft rejection of the transplanted kidney (new) 27 Urinary Tract OBSTRUCTION, 28 RENAL STONES 23 HYDRONEPHROSIS -

Inherited Renal Tubulopathies—Challenges and Controversies

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Inherited Renal Tubulopathies—Challenges and Controversies Daniela Iancu 1,* and Emma Ashton 2 1 UCL-Centre for Nephrology, Royal Free Campus, University College London, Rowland Hill Street, London NW3 2PF, UK 2 Rare & Inherited Disease Laboratory, London North Genomic Laboratory Hub, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children National Health Service Foundation Trust, Levels 4-6 Barclay House 37, Queen Square, London WC1N 3BH, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-2381204172; Fax: +44-020-74726476 Received: 11 February 2020; Accepted: 29 February 2020; Published: 5 March 2020 Abstract: Electrolyte homeostasis is maintained by the kidney through a complex transport function mostly performed by specialized proteins distributed along the renal tubules. Pathogenic variants in the genes encoding these proteins impair this function and have consequences on the whole organism. Establishing a genetic diagnosis in patients with renal tubular dysfunction is a challenging task given the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity, functional characteristics of the genes involved and the number of yet unknown causes. Part of these difficulties can be overcome by gathering large patient cohorts and applying high-throughput sequencing techniques combined with experimental work to prove functional impact. This approach has led to the identification of a number of genes but also generated controversies about proper interpretation of variants. In this article, we will highlight these challenges and controversies. Keywords: inherited tubulopathies; next generation sequencing; genetic heterogeneity; variant classification. 1. Introduction Mutations in genes that encode transporter proteins in the renal tubule alter kidney capacity to maintain homeostasis and cause diseases recognized under the generic name of inherited tubulopathies. -

RENAL BIOPSY and GLOMERULONEPHRITIS by J

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.35.409.604 on 1 November 1959. Downloaded from 604 RENAL BIOPSY AND GLOMERULONEPHRITIS By J. H. Ross, M.D., M.R.C.P. Senior Medical Registrar, The Connaught Hospital, and Assistant, The Mledical Unit, The London Hospital Introduction sufficient to establish a diagnosis in a few condi- Safe methods of percutaneous renal biopsy were tions such as amyloid disease and diabetic first described by Perez Ara (1950) and Iversen glomerulosclerosis, but cortex with at least io and Brun (I95I) who used aspiration techniques. glomeruli is necessary for an accurate assessment Many different methods have since been described; of the renal structure; occasionally, up to 40 the simplest is that of Kark and Muehrcke (1954) glomeruli may be present in a single specimen. who use the Franklin modification of the Vim- The revelation of gross structural changes in Silverman needle. the kidneys of patients who can be recognized Brun and Raaschou (1958) have recently re- clinically as having chronic glomerulonephritis is viewed the majority of publications concerned of little value and does not contribute to manage- with renal biopsy and have concluded that the risk ment or prognosis. In contrast, biopsy specimensProtected by copyright. to the patients is slight. They mentioned three from patients in the early stages of glomerulo- fatalities which have been reported but considered nephritis, particularly those who have developed that, in each case, death was probably due to the the nephrotic syndrome insidiously without disease process rather than the investigation. haematuria or renal failure or who showy no Retroperitoneal haematomata have been recorded evidence of disease other than proteinuria, may in patients with hypertension or uraemia but are provide useful information. -

Effects of Ramipril in Nondiabetic Nephropathy: Improved Parameters of Oxidatives Stress and Potential Modulation of Advanced Glycation End Products

Journal of Human Hypertension (2003) 17, 265–270 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9240/03 $25.00 www.nature.com/jhh ORIGINAL ARITICLE Effects of ramipril in nondiabetic nephropathy: improved parameters of oxidatives stress and potential modulation of advanced glycation end products KSˇ ebekova´1, K Gazdı´kova´1, D Syrova´2, P Blazˇı´cˇek2, R Schinzel3, A Heidland3, V Spustova´1 and R Dzu´ rik 1Institute of Preventive and Clinical Medicine, Bratislava, Slovakia; 2Military Hospital, Bratislava, Slovakia; 3University Wuerzburg, Germany Enhanced oxidative stress is involved in the progres- patients on conventional therapy did not differ signifi- sion of renal disease. Since angiotensin converting cantly from the ramipril group, except for higher Hcy enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) have been shown to improve levels in the latter. Administration of ramipril resulted in the antioxidative defence, we investigated, in patients a drop in blood pressure and proteinuria, while creati- with nondiabetic nephropathy, the short-term effect of nine clearance remained the same. The fluorescent the ACEI ramipril on parameters of oxidative stress, AGEs exhibited a mild but significant decline, yet CML such as advanced glycation end products (AGEs), concentration was unchanged. The AOPP and malon- advanced oxidation protein products (AOPPs), homo- dialdehyde concentrations decreased, while a small rise cysteine (Hcy), and lipid peroxidation products. Ramipril in neopterin levels was evident after treatment. The (2.5–5.0 mg/day) was administered to 12 newly diag- mentioned parameters were not affected significantly in nosed patients for 2 months and data compared with a the conventionally treated patients. Evidence that rami- patient group under conventional therapy (diuretic/ pril administration results in a mild decline of fluores- b-blockers) and with age- and sex-matched healthy cent AGEs is herein presented for the first time. -

Guidelines on Urolithiasis

Guidelines on Urolithiasis C. Türk (chair), T. Knoll (vice-chair), A. Petrik, K. Sarica, A. Skolarikos, M. Straub, C. Seitz © European Association of Urology 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. METHODOLOGY 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Data identification 7 1.3 Evidence sources 7 1.4 Level of evidence and grade of recommendation 7 1.5 Publication history 8 1.5.2 Potential conflict of interest statement 8 1.6 References 8 2. CLASSIFICATION OF STONES 9 2.1 Stone size 9 2.2 Stone location 9 2.3 X-ray characteristics 9 2.4 Aetiology of stone formation 9 2.5 Stone composition 9 2.6 Risk groups for stone formation 10 2.7 References 11 3. DIAGNOSIS 12 3.1 Diagnostic imaging 12 3.1.1 Evaluation of patients with acute flank pain 12 3.1.2 Evaluation of patients for whom further treatment of renal stones is planned 13 3.1.3 References 13 3.2 Diagnostics - metabolism-related 14 3.2.1 Basic laboratory analysis - non-emergency urolithiasis patients 15 3.2.2 Analysis of stone composition 15 3.3 References 16 4. TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH RENAL COLIC 16 4.1 Renal colic 16 4.1.1 Pain relief 16 4.1.2 Prevention of recurrent renal colic 16 4.1.3 Recommendations for analgesia during renal colic 17 4.1.4 References 17 4.2 Management of sepsis in obstructed kidney 18 4.2.1 Decompression 18 4.2.2 Further measures 18 4.2.3 References 18 5. STONE RELIEF 19 5.1 Observation of ureteral stones 19 5.1.1 Stone-passage rates 19 5.2 Observation of kidney stones 19 5.3 Medical expulsive therapy (MET) 20 5.3.1 Medical agents 20 5.3.2 Factors affecting success of medical expulsive -

April 2020 Radar Diagnoses and Cohorts the Following Table Shows

RaDaR Diagnoses and Cohorts The following table shows which cohort to enter each patient into on RaDaR Diagnosis RaDaR Cohort Adenine Phosphoribosyltransferase Deficiency (APRT-D) APRT Deficiency AH amyloidosis MGRS AHL amyloidosis MGRS AL amyloidosis MGRS Alport Syndrome Carrier - Female heterozygote for X-linked Alport Alport Syndrome (COL4A5) Alport Syndrome Carrier - Heterozygote for autosomal Alport Alport Syndrome (COL4A3, COL4A4) Alport Syndrome Alport Anti-Glomerular Basement Membrane Disease (Goodpastures) Vasculitis Atypical Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome (aHUS) aHUS Autoimmune distal renal tubular acidosis Tubulopathy Autosomal recessive distal renal tubular acidosis Tubulopathy Autosomal recessive proximal renal tubular acidosis Tubulopathy Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD) ADPKD Autosomal Dominant Tubulointerstitial Kidney Disease (ADTKD) ADTKD Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD) ARPKD/NPHP Bartters Syndrome Tubulopathy BK Nephropathy BK Nephropathy C3 Glomerulopathy MPGN C3 glomerulonephritis with monoclonal gammopathy MGRS Calciphylaxis Calciphylaxis Crystalglobulinaemia MGRS Crystal-storing histiocytosis MGRS Cystinosis Cystinosis Cystinuria Cystinuria Dense Deposit Disease (DDD) MPGN Dent Disease Dent & Lowe Denys-Drash Syndrome INS Dominant hypophosphatemia with nephrolithiasis or osteoporosis Tubulopathy Drug induced Fanconi syndrome Tubulopathy Drug induced hypomagnesemia Tubulopathy Drug induced Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus Tubulopathy Epilepsy, Ataxia, Sensorineural deafness, Tubulopathy -

Guidelines on Urolithiasis

GUIDELINES ON UROLITHIASIS (Text update April 2010) Ch. Türk (chairman), T. Knoll (vice-chairman), A. Petrik, K. Sarica, C. Seitz, M. Straub, O. Traxer Eur Urol 2001 Oct;40(4):362-71 Eur Urol 2007 Dec;52(6):1610-31 J Urol 2007 Dec;178(6):2418-34 Methodology This update is based on the 2008 version of the Urolithiasis guidelines produced by the former guidelines panel. Literature searches were carried out in Medline and Embase for ran- domised control trials and systematic reviews published between January 1st, 2008, and November 30, 2009, and sig- nificant differences in diagnosis and treatment or in evidence level were considered. Introduction Urinary stone disease continues to occupy an important place in everyday urological practice. The average lifetime risk of stone formation has been reported in the range of 5-10%. Recurrent stone formation is a common problem with all types of stones and therefore an important part of the medical care of patients with stone disease. Classification and Risk Factors Different categories of stone formers can be identified based Urolithiasis 251 on the chemical composition of the stone and the severity of the disease (Table 1). Special attention must be given to those patients who are at high risk of recurrent stone formation (Table 2). Table 1: Categories of stone formers Stone composition Category Non-calcium Infection stones: INF stones Magnesium ammonium phosphate Ammonium urate Uric acid UR Sodium urate Cystine CY Calcium First time stone former, without residual So stones stone or stone fragments. First time stone former, with residual Sres stone or stone fragments. -

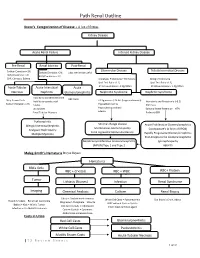

Path Renal Outline

Path Renal Outline Krane’s Categorization of Disease + A lot of Extras Kidney Disease Acute Renal Failure Intrinsic Kidney Disease Pre‐Renal Renal Intrinsic Post‐Renal Sodium Excretion <1% Glomerular Disease Tubulointerstitial Disease Sodium Excretion < 1% Sodium Excretion >2% Labs aren’t that useful BUN/Creatinine > 20 BUN/Creatinine < 10 CHF, Cirrhosis, Edema Urinalysis: Proteinuria + Hematuria Benign Proteinuria Spot Test Ratio >1.5, Spot Test Ratio <1.5, Acute Tubular Acute Interstitial Acute 24 Urine contains > 2.0g/24hrs 24 Urine contains < 1.0g/24hrs Necrosis Nephritis Glomerulonephritis Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritic Syndrome Inability to concentrate Urine RBC Casts Dirty Brown Casts Inability to secrete acid >3.5g protein / 24 hrs (huge proteinuria) Hematuria and Proteinuria (<3.5) Sodium Excretion >2% Edema Hypoalbuminemia RBC Casts Hypercholesterolemia Leukocytes Salt and Water Retention = HTN Focal Tubular Necrosis Edema Reduced GFR Pyelonephritis Minimal change disease Allergic Interstitial Nephritis Acute Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Membranous Glomerulopathy Analgesic Nephropathy Goodpasture’s (a form of RPGN) Focal segmental Glomerulosclerosis Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis Multiple Myeloma Post‐Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis IgA nephropathy (MPGN) Type 1 and Type 2 Alport’s Meleg‐Smith’s Hematuria Break Down Hematuria RBCs Only RBC + Crystals RBC + WBC RBC+ Protein Tumor Lithiasis (Stones) Infection Renal Syndrome Imaging Chemical Analysis Culture Renal Biopsy Calcium -

Prime Mover and Key Therapeutic Target in Diabetic Kidney Disease

Diabetes Volume 66, April 2017 791 Richard E. Gilbert Proximal Tubulopathy: Prime Mover and Key Therapeutic Target in Diabetic Kidney Disease Diabetes 2017;66:791–800 | DOI: 10.2337/db16-0796 The current view of diabetic kidney disease, based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline (2). In meticulously acquired ultrastructural morphometry and recognition of these findings, the term diabetic kidney the utility of measuring plasma creatinine and urinary al- disease rather than diabetic nephropathy is now commonly bumin, has been almost entirely focused on the glomer- used. On the background of recent advances in the role of ulus. While clearly of great importance, changes in the the proximal tubule as a prime mover in diabetic kidney PERSPECTIVES IN DIABETES glomerulus are not the major determinant of renal prog- pathology, this review highlights key recent developments. nosis in diabetes and may not be the primary event in the Published mostly in the general scientific and kidney- development of diabetic kidney disease either. Indeed, specific literature, these advances highlight the pivotal advances in biomarker discovery and a greater appreci- role this part of the nephron plays in the initiation, pro- ation of tubulointerstitial histopathology and the role of gression, staging, and therapeutic intervention in diabetic tubular hypoxia in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney kidney disease. From a pathogenetic perspective, as illus- disease have given us pause to reconsider the current trated in Fig. 1 and as elaborated on further in this review, “glomerulocentric” paradigm and focus attention on the proximal tubule that by virtue of the high energy require- tubular hypoxia as a consequence of increased energy de- ments and reliance on aerobic metabolism render it par- mands and reduced perfusion combine with nonhypoxia- ticularly susceptible to the derangements of the diabetic related forces to drive the development of tubular atrophy fi state. -

Factors in the Cause of Death in Carcinoma of the Cervix

FACTORS IN THE CAUSE OF DEATH IN CARCINOMA OF THE CERVIX A STUDY OF FIFTy-SEVEN CASES COMING TO NECROPSY B]ARNE PEARSON, M.D. (Prom the Cancer Institute and De;artment 01 Pathology, University of Minnesota Medkal School, Minneapolis ) This study is based upon 57 consecutive cases of carcinoma Qf the cervix in which autopsy examinations were performed. Thirty-one of these were studied at the University Hospitals. The remaining 26 were taken from the autopsy records in the Department of Pathology at the University of Minne sota. Microscopic sections were studied except in a few instances in which they could not be obtained. An attempt has been made to determine the im mediate lethal factors and the frequency with which they occur. No attempt is made to determine the efficacy of the treatment. URETERAL STRICTURE Stricture of the ureters with consequent hydronephrosis and hydroureters was the most striking and constant autopsy finding in this series of cases, being present in 42 cases, or 75 per cent. This is in accord with the observations of others. Ernst Holzbach in 4& carcinomas of the cervix coming to autopsy found 31 bilateral and 10 unilateral strictures. Sampson found that the fac tors responsible for strictures were external pressure of a mass of carcinoma around the ureters as a result of parametrial extension and lymphatic metasta sis, and added infection and edema. Carson states that metastasis may occur to the lymphatics of the ureters. Constriction by metastatic processes was not, however, very common in our series. It occurred only three times and was located in the midportion of the ureter. -

Swiss Consensus Recommendations on Urinary Tract Infections in Children

European Journal of Pediatrics https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03714-4 REVIEW Swiss consensus recommendations on urinary tract infections in children Michael Buettcher1 & Johannes Trueck2 & Anita Niederer-Loher3 & Ulrich Heininger4 & Philipp Agyeman5 & Sandra Asner6 & Christoph Berger2 & Julia Bielicki4 & Christian Kahlert3 & Lisa Kottanattu7 & Patrick M. Meyer Sauteur2 & Paolo Paioni2 & Klara Posfay-Barbe8 & Christa Relly2 & Nicole Ritz4 & Petra Zimmermann9 & Franziska Zucol10 & Rita Gobet11 & Sandra Shavit12 & Christoph Rudin 13 & Guido Laube14 & Rodo von Vigier15 & Thomas J. Neuhaus16 Received: 28 July 2019 /Revised: 10 May 2020 /Accepted: 2 June 2020 # The Author(s) 2020, corrected publication 2020 Abstract The kidneys and the urinary tract are a common source of infection in children of all ages, especially infants and young children. The main risk factors for sequelae after urinary tract infections (UTI) are congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) and bladder-bowel dysfunction. UTI should be considered in every child with fever without a source. The differentiation between upper and lower UTI is crucial for appropriate management. Method of urine collection should be based on age and risk factors. The diagnosis of UTI requires urine analysis and significant growth of a pathogen in culture. Treatment of UTI should be based on practical considerations regarding age and presentation with adjustment of the initial antimicrobial treatment according to antimicrobial sensitivity testing. All children, regard- lessofage,shouldhaveanultrasoundoftheurinarytractperformed -

Silent Hydronephrosis/Pyonephrosis Due to Upper Urinary Tract Calculi in Spinal Cord Injury Patients

Spinal Cord (2000) 38, 661 ± 668 ã 2000 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/sc Silent hydronephrosis/pyonephrosis due to upper urinary tract calculi in spinal cord injury patients S Vaidyanathan*,1, G Singh1, BM Soni1, P Hughes2, JWH Watt1, S Dundas3, P Sett1 and KF Parsons4 1Regional Spinal Injuries Centre, District General Hospital, Southport, Merseyside, UK; 2Department of Radiology, District General Hospital, Southport, Merseyside, UK; 3Department of Cellular Pathology, District General Hospital, Southport, Merseyside, UK; 4Department of Urology, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool, UK Study design: A study of four patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) in whom a diagnosis of hydronephrosis or pyonephrosis was delayed since these patients did not manifest the traditional signs and symptoms. Objectives: To learn from these cases as to what steps should be taken to prevent any delay in the diagnosis and treatment of hydronephrosis/pyonephrosis in SCI patients. Setting: Regional Spinal Injuries Centre, Southport, UK. Methods: A retrospective review of cases of hydronephrosis or pyonephrosis due to renal/ ureteric calculus in SCI patients between 1994 and 1999, in whom there was a delay in diagnosis. Results: A T-5 paraplegic patient had two episodes of urinary tract infection (UTI) which were successfully treated with antibiotics. When he developed UTI again, an intravenous urography (IVU) was performed. The IVU revealed a non-visualised kidney and a renal pelvic calculus. In a T-6 paraplegic patient, the classical symptom of ¯ank pain was absent, and the symptoms of sweating and increased spasms were attributed to a syrinx.