Delhi Sultanate Waterworks by Tanvi Gupta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile of Delhi: National Capital Territory

Draft- State Profile Chapter II NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY - DELHI 2.1 General Characteristics Delhi is located in northern India BASIC STATISTICS ABOUT DELHI between the latitudes of 28°-24’-17” • Area: 1,483 sq.Km and 28°-53’-00” North and longitudes • Number of districts: 9 of 76°-50’-24” and 77°-20’-37” East. • Number of Urban villages: Delhi shares bordering with the States • Per Capita income: Rs. 38,864 of Uttar Pradeshand Haryana. Delhi (As per Census2000-01) has an area of 1,483 sq. kms. Its maximum length is 51.90 kms and greatest widthis 48.48 kms. Delhi is situated on the right bank of the river Yamuna at the periphery of the Gangetic plains. It lies a little north of 28 n latitude and a little to the west of 78 longitude. To the west and south-west is the great Indian Thar desert of Rajasthan state, formerly known as Rajputana and, to the east lies the river Yamuna across which has spread the greater Delhi of today. The ridges of the Aravelli range extend right into Delhi proper, towards the western side of the city, and this has given an undulating character to some parts of Delhi. The meandering course of the river Yamuna meets the ridge of Wazirabad to the north; while to the south, the ridge branches off from Mehrauli. The main city is situated on the west bank of the river. 2.2 Physical Features 2.2.1 Geography Delhi is bounded by the Indo-Gangetic alluvial plains in the North and East, by Thar desert in the West and by Aravalli hill ranges in the South. -

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

9-Ravi-Agarwal-Ridge.Pdf

Fight for a forest RAVI AGARWAL From where comes this greenery and flowers? 15% of the city’s land, though much What makes the clouds and the air? of it has been flattened. The decidu- – Mirza Ghalib ous arid scrub forest of the ridge still provides an unique ecosystem, which THE battle for protecting Delhi’s today lies in the heart of the modern green lungs, its prehistoric urban for- city, and is critical for its ecological est, has never been more intense than health. Though citizen’s action has now. The newly global city, located in managed to legally protect1 about a cusp formed by the tail end of the 1.5 7800 ha of the forest scattered in four billion year old, 800 km long Aravalli mountain range as it culminates at the * Ravi Agarwal is member of Srishti and river Yamuna, is the aspirational capi- founding Director of Toxics Link, both envi- 48 tal of over 15 million people. ronmental NGOs. He has been involved in the ridge campaign since 1992, and was inducted The hilly spur known as the into the Ridge Management Board in 2005. Delhi Ridge once occupied almost He is an engineer by training. SEMINAR 613 – September 2010 distinct patches, the fight for the ridge besides protecting the city from desert Dynasty in the 13th and 14th centuries forest has been long and is ongoing. sands blowing in from Rajasthan and marked by the towering Qutab Land is scarce, with competing uses (south of Delhi). Most importantly, for Minar. in the densely populated city, sur- an increasingly water scarce city, the rounded by increasingly urbanized ridge forest and the river Yamuna once peripheral townships of Gurgaon, formed a network of water channels, Even though the Delhi Ridge forest Faridabad and Noida. -

Seismic Hazard Mapping of Delhi City

13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering Vancouver, B.C., Canada August 1-6, 2004 Paper No. 180 SEISMIC HAZARD MAPPING OF DELHI CITY R.N.Iyengar1 and S.Ghosh 2 SUMMARY Delhi the capital of India is a burgeoning metropolis having a population of some twelve million people. The city has experienced earthquakes in the past and is vulnerable for earthquake related damages in the future. There are nearby diffuse seismic sources known for their sporadic activity. In addition, the threat perception is highlighted by the proximity of the active Himalayan plate boundary region. Thus, seismic hazard at Delhi is controlled broadly by two different tectonic regimes namely, the Himalayan region (HR) and the Delhi region (DR). The present study aims at mapping the peak ground acceleration (PGA) values for Delhi city, using probabilistic seismic hazard analysis (PSHA) methods. Twenty potential faults, in a region of 300 km radius around Delhi, are identified. Recurrence relationships for the two controlling regions are established with the help of past (1720-2001A.D.) data. Regional attenuation relationship is developed using strong motion data recorded on rock sites. PSHA is performed for a 40km x 30km region encompassing Delhi and a microzonation map is prepared for PGA value, at a probability exceedance level of 2 percent in a period of 50 years, computed at 1200 grid points at 1km x 1km interval. Disaggregation of hazard in terms of magnitude and source to site distance has also been carried out. This shows that moderate local earthquakes contribute significantly, rather than the long distance Himalayan events, to the hazard in the city. -

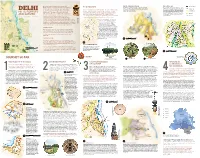

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Ground Water Year Book National Capital Territory, Delhi 2018-19

Ground Water Year Book National Capital Territory, Delhi 2018-19 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD STATE UNIT OFFICE, DELHI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI October - 2020 II FOREWORD Ground Water Year Book is based on the information generated through field studies. The data has been analyzed by Officers of Central Ground Water Board, State Unit Office, Delhi and presented in the report. The reports, annexure and maps have been generated using GEMS Software, Version-2.1, developed indigenously by Central Ground Water Board. Depiction of ground water conditions in Delhi provides information on availability of groundwater in terms of quantity and quality, development prospects and management options. I am happy to note that the scientific information in this report is presented in a simplified form. I sincerely hope this report will be of immense help not only to planners, administrators, researchers and policy makers in formulating development and management strategy but also to the common man in need of such information to make himself aware of the ground situation in NCT Delhi. The untiring efforts made by Sh. Faisal Abrar, Assistant Hydrogeologist, Sh. V Praveen Kumar, STA (Hydrogeology) & Sh. S Ashok Kumar, STA (Hydrogeology) for bringing out this report are highly appreciated. (S K Juneja) Officer in charge Central Ground Water Board State Unit Office, Delhi III IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK 2018-19: NCT DELHI National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi occupies an area of 1483 sq. km. and lies between 28° 24’ 15’’ to 28° 53’ 00’’ N latitudes and 76° 50’ 24” to 77° 20’ 30” E longitudes. -

Groundwater Management in NCT Delhi

Groundwater Management in NCT Delhi Shashank Shekhar1, Raja Ram Purohit2 & Y. B. Kaushik2 1 Asstt. Professor, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 2 Scientist, Central Ground Water Board, Jamnagar House, Mansingh Road, New Delhi – 110011, India. e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract National Capital Territory of Delhi occupies an area of 1483 sq.km. with the population density of 9344 persons/sq.km. The projected population for year 2009 works out to be 176 lakhs and total water requirement for drinking and domestic purposes, 927 million gallons per day (MGD). The Delhi Jal Board (DJB) supplies 815 MGD (including around 100 MGD from groundwater). The deficit in drinking water supply works out to be 112 MGD. This deficit in drinking water supply of Delhi can be partially augmented through exploitation of groundwater resources. The groundwater availability in Delhi area is controlled by the hydrogeological conditions characterized by different geological formations. The major aquifers contributing to the groundwater are fine to medium sand of Older alluvium, medium to coarse sand of Newer alluvium along the Yamuna Flood Plain and the hard rock formations occupied by quartzite, inter-bedded with mica schist belonging to Delhi Super Group. The depth to water in the Delhi state varies greatly from 1.2 meter (in the Yamuna flood plain) to more than 64 meters (in the southern part of the Delhi Ridge) below ground level. The groundwater is declining in majority of the areas of Delhi on account of overexploitation of the resources. The rate of decline is as high as 1.7 to 2 meters/year in some areas (South & South west Dist.). -

Thomas Crowley

THOMAS CROWLEY Institutional Contact Information Address B245, Department of Geography, Lucy Stone Hall, 54 Joyce Kilmer Avenue Piscataway, NJ 08854-8045 Email [email protected] Phone +1 848.445.4103 Education 2017-Present Ph.D. Candidate in Geography, Rutgers University Adviser: Dr. Asher Ghertner 2020 M.A. in Geography, Rutgers University 2007 B.A. in Philosophy, Yale University GPA: 3.87 (Magna Cum Laude, Distinction in Major) Academic Publications Books 2020 Crowley, Thomas. Fractured Forest, Quartzite City: A History of Delhi and its Ridge. New Delhi: Yoda Press/SAGE Select. Peer-reviewed Articles 2020 Crowley, Thomas. “Leisure, Festival, Revolution: Ambedkarite Productions of Space.” CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion 1 (2): 31–50. 2011 Crowley, Thomas. “Climbing Mountains, Hugging Trees: A Cross-cultural Examination of Love for Nature.” Emotion, Space and Ecology 6: 44-53. 2010 Crowley, Thomas. “From ‘Natural’ to ‘Ecosocial Flourishing’: Evaluating Evaluative Frameworks.” Ethics and the Environment 15 (1): 69-100. 2009 Crowley, Thomas. “Mine as metaphor: visions of industry in Tagore and Hamsun.” Indian Journal of Ecocriticism 2. Invited Book Chapters 2011 Crowley, Thomas. “The Poetry of Inclusion: Tukaram, Animals, and the Cosmic One.” In Being for the Other: Ethics and Animal Rights in Literature and Religion, edited by Manish Vyas, 362-375. New Delhi: Daya Publishing House. Book Reviews 2020 Review of Sai Balakrishnan’s Shareholder Cities: Land Transformations Along Urban Corridors in India. Metropolitics. External Grants and Fellowships 2020-2021 American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS) Fellowship for Academic-Year Marathi Language Program 2019 Foreign Language & Area Studies (FLAS) Fellowship U.S. -

The Delhi Ridge

C hattur,excited. theTodaytwowasyearhis firstold jackal,day in school.was veryHis twin-sister Chalaki, too, was going with him. Chattur and Chalaki lived with their parents, and their den was surrounded by lush green forest comprising mostly Kikkar trees. Their school was a clearing under the banyan tree located near the Bistadari Monument, a hunting lodge during the Mughul times. Their teacher Spotty, a wise spotted owl, lived in a hole in the banyan tree. Soon Chalaki and Chattur reached the school and found their seats. Other students of their class also joined them. They all lived in the forest along the Delhi Ridge. Suddenly there was a flutter of wings and their teacher came down from his hole and sat on a high pedestal in front of them. "Good morning, children! I am spotty, your teacher," he introduced himself to the students. "Well, children, let's have a quick round of introduction, one by one." Nila was the fIrst one to start, "I am Nila, the nilgai" .... "I am Kowha, the crow" ... "I am Chalaki, the jackal" .... "I am Totaram, the rose ringed parakeet" ... "I am Pricky, the porcupine" ... "I am Tooktok, the barbet" ... "I am Chattur, the jackal" "I am Sana, the golden oriole" ... "I am Koel" "I am Chintu, the rhesus macaque" "I am Momi, the peahen" .. '. "I am Gilheriy, the squirrel" "I am Slimy, the rat snake" ... ''I am Nevla, Koel. "Let's wait and hear what this old man has to say. the mongoose". If it is good for nothing, then we'll slowly slip away." 'Thank you, children. -

Conservation & Heritage Management

Chapter – 7 : Conservation & Heritage Management IL&FS ECOSMART Chapter – 7 Conservation & Heritage Management CHAPTER - 7 CONSERVATION & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 7.1 INTRODUCTION Heritage Resource Conservation and Management imperatives for Delhi The distinctive historical pattern of development of Delhi, with sixteen identified capital cities1 located in different parts of the triangular area between the Aravalli ridge and the Yamuna river, has resulted in the distribution of a large number of highly significant heritage resources, mainly dating from the 13th century onwards, as an integral component within the contemporary city environment. (Map-1) In addition, as many of these heritage resources (Ashokan rock edict, two World Heritage Sites, most ASI protected monuments) are closely associated with the ridge, existing water systems, forests and open space networks, they exemplify the traditional link between natural and cultural resources which needs to be enhanced and strengthened in order to improve Delhi’s environment. (Map -2) 7.1.1 Heritage Typologies – Location and Significance These heritage resources continue to be of great significance and relevance to any sustainable development planning vision for Delhi, encompassing a vast range of heritage typologies2, including: 1. Archaeological sites, 2. Fortifications, citadels, different types of palace buildings and administrative complexes, 3. Religious structures and complexes, including Dargah complexes 4. Memorials, funerary structures, tombs 5. Historic gardens, 6. Traditional networks associated with systems of water harvesting and management 1 Indraprastha ( c. 1st millennium BCE), Dilli, Surajpal’s Surajkund, Anangpal’s Lal Kot, Prithviraj Chauhan’s Qila Rai Pithora, Kaiquabad’s Khilokhri, Alauddin Khilji’s Siri, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq’s Tughlaqabad, Muhammad Bin Tughlaq’s Jahanpanah, Firoz Shah Tughlaq’s Firozabad, Khizr Khan’s Khizrabad, Mubarak Shah’s Mubarakabad, Humayun’s Dinpanah, Sher Shah Suri’s Dilli Sher Shahi, Shah Jehan’s Shahjehanabad, and Lutyen’s New Delhi. -

Narayani.Pdf

OUR CITY, DELHI Narayani Gupta Illustrated by Mira Deshprabhu Introduction This book is intended to do two things. It seeks to make the child living in Delhi aware of the pleasures of living in a modern city, while at the same time understanding that it is a historic one. It also hopes to make him realize that a citizen has many responsibilities in helping to keep a city beautiful, and these are particularly important in a large crowded city. Most of the chapters include suggestions for activities and it is important that the child should do these as well as read the text. The book is divided into sixteen chapters, so that two chapters can be covered each month, and the course finished easily in a year. It is essential that the whole book should be read, because the chapters are interconnected. They aim to make the child familiar with map-reading, to learn some history without making it mechanical, make him aware of the need to keep the environment clean, and help him to know and love birds, flowers and trees. Our City, Delhi Narayani Gupta Contents Introduction Where Do You Live? The Ten Cities of Delhi All Roads Lead to Delhi Delhi’s River—the Yamuna The Oldest Hills—the Ridge Delhi’s Green Spaces We Also Live in Delhi Our Houses Our Shops Who Governs Delhi? Festivals A Holiday Excursion Delhi in 1385 Delhi in 1835 Delhi in 1955 Before We Say Goodbye 1. Where Do You Live? This is a book about eight children and the town they live in. -

Ashish Kothari Project Director

JPAM UPDATE News on Action Towards Joint Protected Area Management No’s 1 -17 September 1994 - July 1998 ...\ak\jtmng\update\final\onefile.doc Notes: • This file version does not follow page numbering, page layout, fonts, etc. as they appear in hard copies of the Update • The entire file has been reduced to GeoSlab703 Lt BT font in 10 point. (This will appear as Times New Roman in systems where GeoSlab is not installed) 1 Ashish Kothari Project Director 23 November,1994 Dear Friend, As was decided in our September meeting on Exploring Joint Protected Area Management, we shall be starting with a regular Update to inform you of all the activities being undertaken within the purview of joint or participatory management of protected areas. Enclosed please find the first of these Updates. This Update is based on the information received or gathered by us since the workshop in September. It is possible that we have missed out on other follow-up being carried out by some of you; please inform us immediately so that we can include it in the next Update. Your comments on the Update are also eagerly awaited. Most important, however, PLEASE DO KEEP INFORMING US OF RELATED ACTIVITIES AND ANY OTHER INFORMATION WHICH YOU THINK WOULD BE OF USE TO OTHERS AND WHICH SHOULD BE INCLUDED IN FUTURE ISSUES. Mean while, I hope you have received the notice and invitation to the Protect Forests Protect Forest Dwellers Yatra that some of us are proposing to hold in January-February. If you have not already responded, Please do so immediately, as planning time is very short.