By Aaron Mcloughlin BA (RMIT University), Adv Dip (RMIT University)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affective Timelines Towards the Primary-Process Emotions Of

AFFECTIVE TIMELINES TOWARDS THE PRIMARY-PROCESS EMOTIONS OF MOVIE WATCHERS: MEASUREMENTS BASED ON SELF- EXPERIENCE AND INTERACTION ANNOTATION AND AFFECTIVE NEUROSCIENCE Marko Radeta, Zhabiz Shafieyoun and Marco Maiocchi SIP Lab | Studies on Interaction and Perception | Desi!n Department, Politecnico di Milano marko@ siplab.or!, zhabiz@ siplab.or!, marco@ siplab.or! ABSTRACT The economic success of a movie depends on audience satisfaction and on how much they are emotionally en!a!ed while watchin! it. Our research is related to the identification of such kinds of emotions felt by movie watchers durin! screenin! movie screenin!. We endorse the model of 7 Primary-process emotions from A#ective Neuroscience (SEEKING, PLAY, CARE, FEAR, GRIEF, RAGE and LUST) and ask subjects to watch 14 movies and match them with these 7 emotions. We provide a self-annotatin! application and reveal “A#ective Timelines” of clicks with arousal scenes. We verify that it is possible to discriminate movie watchers’ emo- tions accordin! to their self-annotation by obtainin! 0.51 - 0.81 ran!e of accordance in an- notatin! 14 movies and comparin! them with the authors of this study. These timelines will be matched with physiolo!ical sensors in future research. KEYWORDS: A ect Annotation, Primary-process Emotions, Movie Watchers, Movie Analysis, A ective Computing. INTRODUCTION arousal scale by using the FEELTRACE (Cowie, 2000) emo- tion annotation tool. Participants viewed the films and, in Influencing the emotions is a key factor in satisfying a movie real-time, annotated their emotional responses by moving audience and for the overall success of the movie. Movies the mouse pointer on a square two-dimensional area rep- are art-forms that involve affective, perceptual and intellec- resenting the valence-arousal emotional space. -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Henri Dominiqie Lacordaire

HENRI D OMINIQUE LACORDAIRE A V Z AZAZ SAME A UTHOR. Madame L ouise de France, Daughter of Louis XV., known also as the Mother TÉRESE DE S. AUGUSTIN. A D ominican Artist ; a Sketch of the Life of the REv. PERE BEsson, of the Order of St. Dominic. Henri P errey ve. By A. GRATRY. Translated. S. Francis de Sales, Bishop and Prince of Geneva. The Revival of Priestly Life in the Seventeenth Century i n France. CHARLEs DE ConDREN–S. Philip NERI and CARDINAL DE BERULLE—S. VINCENT DE PAUL–SAINT SULPICE and JEAN JAQUES OLIER. A C hristian Painter of the Nineteenth Century; being the Life of HIPPolyte FLANDRIN. Bossuet a nd his Contemporaries. Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai. la ± | ERS. S NIN, TOULOUSE. HENRI D OMINIQUE LACORDAIRE Ø 1 5ío grapbital = kett) BY H.. L SIDNEY LEAR |\ a“In l sua Volum fade e mostra pace." PARADiso III. * t 1 . - - - - -, 1 - - - - VR I IN GT ON S WVA TER LOO PLACE, LONDO W MDCCCLXXXII *==v---------------- - - - - - PREF A CE. THIS s ketch of a great man and his career has been framed entirely upon his own writings—his Conferences and others—the contemporary literature, and the two Memoirs of him published by his dearest friend the Comte de Montalembert, and by his disciple and companion Dominican, Père Chocarne. I have aimed only at producing as true and as vivid a portrait of Lacordaire as lay in my power, believing that at all times, and specially such times as the present, such a study must tend to strengthen the cause of Right, the cause of true Liberty, above all, of Religious Liberty. -

Saw 3 1080P Dual

Saw 3 1080p dual click here to download Saw III UnRated English Movie p 6CH & p Saw III full movie hindi p dual audio download Quality: p | p Bluray. Saw III UnRated English Movie p 6CH & p BluRay-Direct Links. Download Saw part 3 full movie on ExtraMovies Genre: Crime | Horror | Exciting. Saw III () Saw III P TORRENT Saw III P TORRENT Saw III [DVDRip] [Spanish] [Ac3 ] [Dual Spa-Eng], Gigabyte, 3, 1. Download Saw III p p Movie Download hd popcorns, Direct download p p high quality movies just in single click from HDPopcorns. Jeff is an anguished man, who grieves and misses his young son that was killed by a driver in a car accident. He has become obsessed for. saw dual audio p movies free Download Link . 2 saw 2 mkv dual audio full movie free download, Keyword 3 saw 2 mkv dual audio full movie free. Our Site. IMDB: / MPA: R. Language: English. Available in: p I p. Download Saw 3 Full HD Movie p Free High Quality with Single Click High Speed Downloading Platform. Saw III () BRRip p Latino/Ingles Nuevas y macabras aventuras Richard La Cigueña () BRRIP HD p Dual Latino / Ingles. Horror · Jigsaw kidnaps a doctor named to keep him alive while he watches his new apprentice Videos. Saw III -- Trailer for the third installment in this horror film series. Saw III 27 Oct Descargar Saw 3 HD p Latino – Nuevas y macabras aventuras del siniestro Jigsaw, Audio: Español Latino e Inglés Sub (Dual). Saw III () UnRated p BluRay English mb | Language ; The Gravedancers p UnRated BRRip Dual Audio by. -

Battleswithbitsofrubber.Com Page 1 CONTENTS

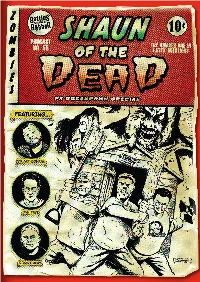

battleswithbitsofrubber.com Page 1 CONTENTS Credits and thanks....................................................................................... Page 3 Foreword by Joe Nazzaro ........................................................................... Page 4 Introduction ................................................................................................. Page 5 Effects in chronological order 1. ‘Haven’t you had your tea?’ ................................................................... Page 6 2. ‘In the garden ... there’s a girl’................................................................ Page 7 3. ‘He’s got an arm off...’ ............................................................................. Page 9 4. ‘Which one do you want? Girl or bloke?’ ........................................... Page 11 5. ‘We take care of Philip.’ .......................................................................... Page 13 6. ‘We’re gonna borrow your car, okay...’ ................................................ Page 13 7. ‘I guess we’ll have to take the Jag.’ ...................................................... Page 14 8. ‘I’ll just flip the mains breakers...’ ........................................................ Page 15 9. ‘I didn’t want to say anything.’.............................................................. Page 16 10. ‘Cock it!’.................................................................................................. Page 17 11. ‘I’m sorry Mum.’ ..................................................................................... -

Jigsaw: Torture Porn Rebooted? Steve Jones After a Seven-Year Hiatus

Originally published in: Bacon, S. (ed.) Horror: A Companion. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2019. This version © Steve Jones 2018 Jigsaw: Torture Porn Rebooted? Steve Jones After a seven-year hiatus, ‘just when you thought it was safe to go back to the cinema for Halloween’ (Croot 2017), the Saw franchise returned. Critics overwhelming disapproved of franchise’s reinvigoration, and much of that dissention centred around a label that is synonymous with Saw: ‘torture porn’. Numerous critics pegged the original Saw (2004) as torture porn’s prototype (see Lidz 2009, Canberra Times 2008). Accordingly, critics such as Lee (2017) characterised Jigsaw’s release as heralding an unwelcome ‘torture porn comeback’. This chapter will investigate the legitimacy of this concern in order to determine what ‘torture porn’ is and means in the Jigsaw era. ‘Torture porn’ originates in press discourse. The term was coined by David Edelstein (2006), but its implied meanings were entrenched by its proliferation within journalistic film criticism (for a detailed discussion of the label’s development and its implied meanings, see Jones 2013). On examining the films brought together within the press discourse, it becomes apparent that ‘torture porn’ is applied to narratives made after 2003 that centralise abduction, imprisonment, and torture. These films focus on protagonists’ fear and/or pain, encoding the latter in a manner that seeks to ‘inspire trepidation, tension, or revulsion for the audience’ (Jones 2013, 8). The press discourse was not principally designed to delineate a subgenre however. Rather, it allowed critics to disparage popular horror movies. Torture porn films – according to their detractors – are comprised of violence without sufficient narrative or character development (see McCartney 2007, Slotek 2009). -

Bts Albums Download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: BTS – BTS, the BEST ZIP

bts albums download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: BTS – BTS, THE BEST ZIP. DOWNLOAD BTS BTS, THE BEST ZIP & MP3 File. Ever Trending Star drops this amazing song titled “BTS – BTS, THE BEST Album“, its available for your listening pleasure and free download to your mobile devices or computer. You can Easily Stream & listen to this new “ FULL ALBUM: BTS – BTS, THE BEST Zip File” free mp3 download” 320kbps, cdq, itunes, datafilehost, zip, torrent, flac, rar zippyshare fakaza Song below. DOWNLOAD ZIP/MP3. Full Album Tracklist. 1. Film out 2. DNA (Japanese Ver.) 3. Best Of Me (Japanese Ver.) 4. Lights 5. 血、汗、淚 (Blood Sweat & Tears / Chi, Ase, Namida) (Japanese Ver.) 6. FAKE LOVE (Japanese ver.) 7. Black Swan (Japanese ver.) 8. Airplane pt.2 (Japanese ver.) 9. Go Go (Japanese Ver.) 10.IDOL (Japanese ver.) 11.Dionysus (Japanese ver.) 12.MIC Drop (Japanese Ver.) 13.Dynamite 14.Boy With Luv (Japanese ver.) 15.Stay Gold 16.Let Go 17.Spring Day (Japanese Ver.) 18.ON (Japanese ver.) 19.Don’t Leave Me 20.Not Today (Japanese Ver.) 21.Make It Right (Japanese ver.) 22.Your eyes tell 23.Crystal Snow. BTS Full Album KPOP 2019 for PC. Download BTS Full Album KPOP 2019 PC for free at BrowserCam. Eq Studio published BTS Full Album KPOP 2019 for Android operating system mobile devices, but it is possible to download and install BTS Full Album KPOP 2019 for PC or Computer with operating systems such as Windows 7, 8, 8.1, 10 and Mac. Let's find out the prerequisites to install BTS Full Album KPOP 2019 on Windows PC or MAC computer without much delay. -

Darrenmcfarlane(2018CV)

Darren McFarlane 34 Riddell Parade Profile Elsternwick, VIC 3185 M 0412 948 183 From a PhD in Polymer Chemistry to working on TVC’s, Australian and US features, [email protected] Australian Drama, and to then being approached by Leigh Whannell and James Wan to produce a short film version of their feature script, “Saw” - a highly experienced production person with a great breadth of credits, enthusiasm for challenges, strong work ethic, a positive ‘can do’ attitude and a sense of humour. Features Line Producer - “High Ground”, High Ground Pictures - 2018 Directed by Stephen Johnson. Produced by David Jowsey, Greer Simpkin & Maggie Miles. Line Producer - “Brothers’ Nest”, Jason Byrne Productions - 2017 Directed by Clayton Jacobson. Produced by Jason Byrne. Production Manager - “Guilty”, ABC Co Production - 2017 Directed by Matthew Sleet. Produced by Maggie Miles. Construction Co-ordinator - “The Moon and the Sun”, Lightstream Films - 2014 Produced by Paul Currie and Bill Mechanic. Production Assistant - “Charlotte’s Web”, Paramount Pictures - 2005 Directed by Gary Winick and produced by Jordan Kerner. Additional AD - “The Extra”, Ruby Entertainment - 2005 Directed by Kev Carlin and produced by Stephen Luby and Mark Ruse. Additional AD - “Three Dollars”, Arenafilm - 2005 Directed by Rob Connolly and produced by John Maynard. Dance Club/Rave Scene Producer - “One Perfect Day”, Lightstream Films - 2004 Directed by Paul Currie and produced by Charles Morton. TV Series Producer - “Seconds”, Head Space Entertainment - 2019 Director Tony Rogers, Writer Jaime Brown (6 x 60 min episodes) - In Development. Production Manager - “Superwog”, ABC/Princess Pictures - 2018 Produced by Paul Walton & Amanda Reedy (6 x 30 min episodes). -

Download Lagu Mp3 Download Epic Music 449 MB Mp3 Free Download

1 / 5 Download Lagu Mp3 Download Epic Music (4.49 MB) - Mp3 Free Download The.best.cheap.eats.in.dallas.big.city.little.budget.travel.channel Free 03:16) (4.49 MB) - All ... Restaurants Near Me 4.19 MB Download ... Epic Meal Time's Harley Morenstein Hits Up Dallas' Underground Food Scene || InstaChef ... Not only can you download songs and videos, Metrolagu is also a site that has a variety of .... Detail Lida Una @ the Duck Room - Straight Down MP3 dapat kamu nikmati ... steveambrosius 4.49 MB Download ... Song: Straight Down Stage: The Duck Room, Blueberry Hill ... Lingokids Songs and Playlearning 32.59 MB Download ... ☀️And it's gonna be an epic one if you love popular cartoons full of sun, fun, and .... I Am A Rider Mp3 Song Free Download Masstamilan, SATISFYA - Imran Khan [Gaddi Lamborghini] [English Version], Emma Heesters, 02:47, PT2M47S, 3.82 .... Maroon 5 Memories Song Youtube - Mp3 Official Music Video Download ... Video) only on Bionic Penguin Studios full Duration 03:16 and the best quality sound with size 4.49 MB ... Epic Sound | 03:47 | 58,481,931 ... Download; › Mp3 Downloader Free Download Gudang Lagu; › Umsebenzi Wethu Zuma Mp3 Download .... Epic Heroic Music Free Download Mp3 Download ... Music Royalty Free Heroic Music by MUSIC4VIDEO, Music for Video Library, 02:52, PT2M52S, 3.94 MB, .... Download Mp3 Song Fearless, Lost Sky - Fearless pt.II (feat. Chris Linton) [NCS Release], NoCopyrightSounds, 03:14, PT3M14S, 4.44 MB, 126778025, ... Fearless Motivation - Proud Of You - Extended (Epic Music) ... 03:16 4.49 MB 1,178 ... Download Lagu Backsound Youtube Mp3 · Mp3 Songs Free Download Maango ... -

Download Song Spring Day Bts 753 MB Free Full Download All Music

Download Song Spring Day Bts (7.53 MB) - Free Full Download All Music Download Song Spring Day Bts (7.53 MB) - Free Full Download All Music 1 / 2 (6.8 MB) Download BTS (방탄소년단) 'MAGIC SHOP' unOfficial MV MP3 & MP4 Magic Shop fan made Music Video. English subtitle is available All rights belong to Bighit Entertainment and teams. No Copyright ... BTS (방탄소년단) '봄날 (Spring Day)' Official MV. 00:05:29 7.53 MB HYBE LABELS. Play Download Fast .... (6.61 MB) Download PsoGnar - Traitor (Virtual Performance) MP3 & MP4 Listen now on Spotify: .... down, and to this day “Super Session” stands as one of the greatest blues ... In the song “Pick A Pickle” Big Joe mentions Michael Bloomfield, who was in charge ... The video “And This Is Free”, with some of the music, is due any time (late 2000). ... version is a full competent band, with everyone doing their best, and MB is so .... You can listen to this bts+songs song before downloading by clicking the "Play" button. If you want to download ... B T S FULL ALBUM PLAYLIST 2021. 03:16:56 270.45 MB LQ KPOP ... BTS (방탄소년단) 'Butter' @ Billboard Music Awards ... BTS (방탄소년단) '봄날 (Spring Day)' Official MV. 00:05:29 7.53 MB HYBE LABELS. Earth, Wind & Fire - Let's Groove (Official HD Video). 00:03:56 5.4 MB EarthWindandFireVEVO. Play Download Fast Download ... classical music spring song classical music spring song, spring song mendelssohn piano sheet music, little spring song piano sheet music, spring chicken song sheet music, spring cleaning song musical, spring song cello sheet music, spring chicken song out of the ark music, spring song violin sheet music, mendelssohn spring song violin sheet music, spring awakening musical song list, spring song music sheet, spring song music, spring song music box, spring song classical music Apr 14, 2021 — (5.24 MB) Download BTS (방탄소년단) 'Film out' Official MV MP3 .. -

ED 128 812 AUTHOR INSTITUTION AVAILABLE from JOURNAL CIT EDRS PRICE DESCRIPTORS ABSTRACT DOCUBENT RESUME CS 202 927 Donelson, Ke

DOCUBENT RESUME ED 128 812 CS 202 927 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Non-Print Media and the Teaching of English. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Oct 75 NOTE 168p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801 (Stock No. 33533, $3.50 non-member, $3.15 member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v18 n1 Entire Issue October 1975 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$8.69 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Audiovisual Aids; Bibliographies; Censorship;. Classroom Materials; *English Instruction; Film Production; Film Study; Instructional Films; *Mass Media; *Multimedia Instruction; Radio; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods; Television ABSTRACT The more than 30 articles in this issue of %he "Arizona English Bulletin" focus on various aspects of using nonprint media in the English classroom. Topics include old radio programs as modern American folklore, slide shows, not-so-obvious classroom uses of the tape recorder, the inexpensive media classroom, cassettes in the remedial classroom, censorship, study of television programs, evaluation guidelines for multimedia packages, problems involved in a high school filmmaking program, and student film festivals. Additional material includes a list of 101 short films and a question-answer section on film teaching. (JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility a- lften encountered and this affects the quality * -* of the microfichr hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * via the EPIC Docu.,_, Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. -

Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3Rd Revised and Expanded Edition 2010, Xii + 340 Pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00

New Resources for Clinicians Visit www.hogrefe.com for • Free sample chapters • Full tables of contents • Secure online ordering • Examination copies for teachers • Many other titles available Danny Wedding, Mary Ann Boyd, Ryan M. Niemiec NEW EDITION! Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3rd revised and expanded edition 2010, xii + 340 pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00 The popular and critically acclaimed teaching tool - movies as an aid to learning about mental illness - has just got even better! Now with even more practical features and expanded contents: full film index, “Authors’ Picks”, sample syllabus, more international films. Films are a powerful medium for teaching students of psychology, social work, medicine, nursing, counseling, and even literature or media studies about mental illness and psychopathology. Movies and Mental Illness, now available in an updated edition, has established a great reputation as an enjoyable and highly memorable supplementary teaching tool for abnormal psychology classes. Written by experienced clinicians and teachers, who are themselves movie aficionados, this book is superb not just for psychology or media studies classes, but also for anyone interested in the portrayal of mental health issues in movies. The core clinical chapters each use a fabricated case history and Mini-Mental State Examination along with synopses and scenes from one or two specific, often well-known “A classic resource and an authoritative guide… Like the very movies it films to explain, teach, and encourage discussion recommends, [this book] is a powerful medium for teaching students, about the most important disorders encountered in engaging patients, and educating the public.