Read a Sample of Constant Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunshine State

SUNSHINE STATE A FILM BY JOHN SAYLES A Sony Pictures Classics Release 141 Minutes. Rated PG-13 by the MPAA East Coast East Coast West Coast Distributor Falco Ink. Bazan Entertainment Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Evelyn Santana Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Jackie Bazan Ziggy Kozlowski Marissa Manne 850 Seventh Avenue 110 Thorn Street 8271 Melrose Avenue 550 Madison Avenue Suite 1005 Suite 200 8 th Floor New York, NY 10019 Jersey City, NJ 07307 Los Angeles, CA 9004 New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212-445-7100 Tel: 201 656 0529 Tel: 323-655-0593 Tel: 212-833-8833 Fax: 212-445-0623 Fax: 201 653 3197 Fax: 323-655-7302 Fax: 212-833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com CAST MARLY TEMPLE................................................................EDIE FALCO DELIA TEMPLE...................................................................JANE ALEXANDER FURMAN TEMPLE.............................................................RALPH WAITE DESIREE PERRY..................................................................ANGELA BASSETT REGGIE PERRY...................................................................JAMES MCDANIEL EUNICE STOKES.................................................................MARY ALICE DR. LLOYD...........................................................................BILL COBBS EARL PICKNEY...................................................................GORDON CLAPP FRANCINE PICKNEY.........................................................MARY -

Introduction

I strive to write interesting and different scenarios. I didn’t Introduction want this one to fall into the same old tropes that had Remember when your babysitter or big brother or bigger been so overused that it had actually become a Mythos sister would sit on you and tickle you until you cried? cliché. I related my fears to Jeff Campbell, and he agreed. Remember how horrible and violated you felt? Yes, you “Why don’t you make your bad guy an alien from the were laughing, but you weren’t having fun. future, like in Through the Gate of the Silver Key?” he What if you could make people laugh like that, but asked—brilliantly—and the scenario had its newer, non- without touching them—just by telling a joke? Maybe you Nyarlathotep ending that you will read shortly. learned it from a book, or maybe someone taught you, Yet it wasn’t enough to just have a new antagonist. but you could make people laugh simply by saying certain One significant difference between fiction and RPG is words. It would come with a price, of course, and wouldn’t group collaboration. The best RPGs give all the players be fun for those suffering its effects. Just like when your something to work out on their own, and what is a brother tickled you until you cried. good horror game without hallucinations, paranoia and That question crossed my mind back in 2010 and just confusion? So I made the new antagonist a future version stuck there. Such an interesting premise for a modern of one of the PCs, thus bringing the story inward for the scenario—in this day of highly successful comedians such players to understand: Why does one of our friends look as Patton Oswalt and Louis CK, being able to just switch like one of the bad guys? on the applause would be a temptation hard to resist. -

The Artillery of Critique Versus the General Uncritical Consensus: Standing up to Propaganda, 1990-1999

THE ARTILLERY OF CRITIQUE VERSUS THE GENERAL UNCRITICAL CONSENSUS: STANDING UP TO PROPAGANDA, 1990-1999 by Andrew Alexander Monti Master of Arts, York University, Toronto, Canada, 2013 Bachelor of Science, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy, 2005 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Joint Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2018 © Andrew Alexander Monti, 2018 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The Artillery of Critique versus the General Uncritical Consensus: Standing Up to Propaganda, 1990-1999 Andrew Alexander Monti Doctor of Philosophy Communication and Culture Ryerson University, 2018 In 2011, leading comedy scholars singled-out two shortcomings in stand-up comedy research. The first shortcoming suggests a theoretical void: that although “a number of different disciplines take comedy as their subject matter, the opportunities afforded to the inter-disciplinary study of comedy are rarely, if ever, capitalized on.”1 The second indicates a methodological void: there is a “lack of literature on ‘how’ to analyse stand-up comedy.”2 This research project examines the relationship between political consciousness and satirical humour in stand-up comedy and attempts to redress these two shortcomings. -

Comedy: Stand-Up, Gay Male by Tina Gianoulis Actor and Comic Jason Stuart

Comedy: Stand-Up, Gay Male by Tina Gianoulis Actor and comic Jason Stuart. Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy JasonStuart. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. com. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Stand-up comedy is a form of entertainment where one performer stands in front of an audience and tries to make common cause with that audience by pointing out the ridiculous and humorous in the universal problems of everyday life. Stand-up comics balance on a fine edge between the funny and the offensive. They can be social critics, prodding audiences to look at the unfairness and inequality in life and to rise above them with a laugh. They can also be part of that unfairness by using humor to make fun of women, gays, and ethnic groups, allowing some members of their audiences to feel superior to those who are the butts of the joke. The dilemma is well expressed by Henry Machtey on the Gay Comedy Links website: "Stand-up comedy. Cracking jokes. Are you going to aim those jokes at people who are less powerful? or people who are more powerful?" Too often, gay men have been the objects of hostile humor. Queer jokes, like female jokes and ethnic jokes, have long been a staple of straight stand-up comics looking for an easy laugh from audiences eager to assert their own heterosexuality in a world where it is often dangerous to be gay. At the same time, however, perhaps long before the all-male Greek theater of the fourth century B.C.E., audiences have also had a fascination with gender-bending. -

Twenty Comic Masks

Twenty Comic Masks Which One are You? Comic Mask Real World Example 1 The Stand-Up Jerry Seinfeld, Amy Schumer 2 The Aggressor Bill Burr, Chelsea Handler, Jim Jefferies, Bill Hicks, Whitney Cummings, Chelsea Handler 3 The Sad Sack Richard Lewis, Rodney Dangerfield, Gary Shandling 4 The Druggie Rebel Sam Kinison, Sandra Bernhardt, Lenny Bruce, Kat Williams 5 The Intellectual Jon Stewart, John Hodgman, Woody Allen, Mitch Hedberg, Steven Wright 6 The Socio-Political Satirist Jon Stewart, George Carlin, Lewis Black, Chris Rock, Bill Maher 7 The Storyteller Bill Cosby, Louis CK, Kevin Hart, Richard Pryor 8 The Rube Larry the Cable Guy, Jeff Foxworthy, Ron White, Bill Engvall 9 The Old-Timer George Burns, Mrs. Hughes 10 The Ethnic Type George Lopez, Maz Jobrani, Aziz Ansari, Katt Williams 11 The Immigrant Ricky Gervais, Maureen Murphy, Craig Ferguson THE TEAM 12 Partners Smothers Brothers, Key & Peele, Penn & Teller 13 The Sketch Performer Key & Peele, Monty Python, Kids in the Hall 14 The Ventriloquist Jeff Dunham, Terry Fator, Triumph, The Insult Dog THE ACTORS 15 The Impersonator Terry Fator, Jim Carrey, Kevin Pollack, Frank Caliendo 16 The Artists, Musicians, Bo Burnham, Kevin Nealon, Cartoonists Zach Galifianakis, Jimmy Fallon 17 The Vaudevillian Penn & Teller, The Flying Karamazov Brothers (Other Jugglers, Magicians and acrobats) 18 The Improvisors Lily Tomlin, Jonathan Winters, Robin Williams 19 The Buffoon/The Airhead Andrew “Dice” Clay, Larry the Cable Guy, Rita Rudner 20 The Prop Comic Carrot Top, Gallagher, Do you fit into any of these categories? Maybe you’re so unique you are creating your own? Wouldn’t that be exciting! *Note: This is not a scientific study and some comedians can easily fit in multiple categories, this is just a guide and an example of character, persona and point of view through the ‘mask’ of the fictional character. -

A Well-Respected Comedian Whose Been Compared to a Tornado on Amphetamines

STEVE PEARL - Comedian, Writer, Director, Air-guitarist Extraordinaire! Fee: $2500/exp – California Based A well-respected comedian whose been compared to a tornado on amphetamines. His high-energy comedy act is both outrageous and hysterically original. Born in Far Rockaway, and raised on Long Island New York. Steven Pearl has been performing stand-up comedy professionally since 1979. He began his stand-up career in such prestigious NYC comedy clubs as Catch A Rising Star and The Improv, moving to San Francisco in 1979. In San Francisco he immersed himself in the comedy scene and was often performing seven nights a week. By 1985, he found himself opening for the then up and coming L.A. based comic Sam Kinison. He eventually discovered a comedian could only go so far in San Francisco and moved on to Los Angeles in 1987. In L.A. he was quickly made a paid regular at the world-famous Comedy Store on Sunset Strip. In his first days there he suddenly found himself following such legendary comedy acts as Sam Kinison, Richard Pryor and Roseanne. In the highly competitive world of the 1980s L.A. comedy scene, he held his own and continued to grow both as a writer and performer. In the late 1980s he began appearing on numerous TV shows, including _A & E's An Evening at the Improv (1985)_ , and Caroline's Comedy Hour (1989). During this same period he began touring extensively clubs, colleges, and festivals all across the U.S. and around the world._ _ Some of his many credits include writing for and working with such comedic legends as Sam Kinison, Bill Hicks, Jim Carrey, Robin Williams and Rodney Dangerfield._ _ A true journeyman comic, Steven Pearl continues to push the envelope of both good taste and sanity. -

Comedy in Bloomington

(clockwise, from top left) The Comedy Attic’s proprietor, Jared Thompson, surrounded by cuddly friends. Tig Notaro, the opening headliner at last year’s Limestone Comedy Festival, gets down to the level of her audience. Photo by Tall + Small Photography The marquee at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater. Photo by Tall + Small Photography Bloomington- based touring comic Ben Moore. Pizza magnate and longtime Comedy Caravan supporter Ray McConn. By Jeremy Shere • Photography by Shannon Zahnle comedy mington in The Art and Business of Bl Making People Laugh 92 Bloom | April/May 2014 | magbloom.com magbloom.com | April/May 2014 | Bloom 93 enjoyed a golden age of comedy. It began in led the way, introducing fans to a new brand of He and Sobel agreed to try comedy at une 8, 2013. The Buskirk- the late-1970s and owes a debt, indirectly, to smart, socially conscious comedy. By the Bear’s Place on Monday nights. This time, Chumley Theater is packed. the launch of television’s Monday Night mid-80s, comedy clubs based on the East and McConn promoted the show heavily, and on It’s the closing night of Bloom- Football telecasts. For a few years, before most West coasts had spawned national franchises Monday, Jan. 10, 1983, comics Rob Haney, ington’s inaugural Limestone people had big TVs, football fans flocked to while TV shows such as A&E’s An Evening at Dea Staley, and Teddy LeRoi played to a full Comedy Festival. The Bear’s Place on East 3rd Street — one of the the Improv and HBO’s Comedy Hour and house. -

George Carlin 1 George Carlin

George Carlin 1 George Carlin George Carlin Carlin in Trenton, New Jersey on April 4, 2008 Birth name George Denis Patrick Carlin Born May 12, 1937Manhattan, New York, U.S. Died June 22, 2008 (aged 71)Santa Monica, California, U.S. Medium Stand-up, television, film, books, radio Nationality American Years active 1956–2008 Genres Character comedy, observational comedy, Insult comedy, wit/word play, satire/political satire, black comedy, surreal humor, sarcasm, blue comedy Subject(s) American culture, American English, everyday life, atheism, recreational drug use, death, philosophy, human behavior, American politics, parenting, children, religion, profanity, psychology, Anarchism, race relations, old age, pop culture, self-deprecation, childhood, family [1] [2] [2] [3] [4] [5] [2] [5] [2] [5] Influences Danny Kaye, Jonathan Winters, Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, Jerry Lewis, Marx Brothers, Mort [4] [5] [5] [2] [5] Sahl, Spike Jones, Ernie Kovacs, Ritz Brothers Monty Python [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] Influenced Chris Rock, Jerry Seinfeld, Bill Hicks, Jim Norton, Sam Kinison, Louis C.K., Bill Cosby, Lewis Black, Jon [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] Stewart, Stephen Colbert, Bill Maher, Denis Leary, Patrice O'Neal, Adam Carolla, Colin Quinn, Steven [17] [18] [19] [19] [20] Wright, Russell Peters, Jay Leno, Ben Stiller, Kevin Smith Spouse Brenda Hosbrook (August 5, 1961 — May 11, 1997) (her death) 1 child [21] Sally Wade (June 24, 1998 — June 22, 2008) (his death) Notable works Class Clown and roles "Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television" Mr. Conductor -

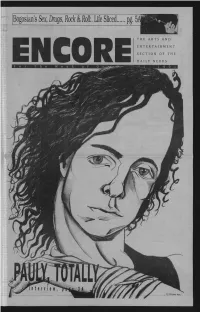

THEATRE at UCSB Eyes of the Dragon and 10 Can Afford

2A Thursday, October 31,1991 lents Santa Barbara Scene larence Thomas? Pauly Shore his social Old hatl It’s time to graces (exemplified so well concentrate on our u our cover story), Sam Ki- C own sin for a while, nison, will be at the Ana most notably tonight’s Hal conda this Friday, Nov. 1. loween festivities. But, as Call 685-5901 and hear Sam you’re descending into the himself tell you how much hell that is human nature, tickets are, as well as a nifty here are a few upcoming little story about necrophil- events on which to ponder iacs in Denver. your pumpkin: • George Wallace and M u s ic . Dennis Wolfberg will be at • The Anaconda presents the Ventura Theatre Satur its Halloween Blowout, be day, Nov. 2. Word is, they’re ginning at 6 p.m. and featur “ topically funny,” as op ing the uneven talents o f posed to the kind of funny bands like Kronix, Creature you just swallow with a glass Feature, Socket and the Su o f water. Make sure to tell preme Love Gods; all head Cast members of Museum discover the them that “if it bends, it’s lined by the promising MC aesthetic of whiteness on an empty canvas. funny. If it breaks, it’s not 900 F t Jesus (see review this funny,” preferably when issue). Rumour has it that S ta te . brought to the fore” this Sa you run into them in the loo. the bald rap/jazz/soul artist • The UCSB drama de turday, Nov. -

Laugh Fa C Tory

The Kings of Ktown is a stand up comedy special featuring Danny Cho, Walter Hong and Paul “PK” Kim. Kings of Ktown Each comedian will deliver their views on culture, race, family and OVERVIEW livin’ like a King in Koreatown in front of a live audience on July 2nd at the World Famous Laugh Factory in Hollywood. The live show will be filmed as a 1 hour special and will feature them performing stand up comedy as well as behind the scenes footage of the comics backstage, partying in Ktown and promoting the special. WWW.KINGSOFKTOWN.COM 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT OVERVIEW Kings of Ktown stand Up Comedy show + 1 Hour special DVD film taping WHEN Thursday July 2nd, 2015 Showtime: 10 PM WHERE World Famous Laugh Factory 8001 Sunset Blvd Hollywood, CA ATTENDANCE Hosted by: Dumbfoundead Expected attendance: 300 (Limited invitations to: celebrity guests, tastemakers, industry folks, guestlist, & sponsors) WWW.KINGSOFKTOWN.COM 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT AUDienCe AUDIENCE According to 2010 Census, approximately 1.7 million people of Korean descent reside in the U.S., making it the country with the second largest Korean population living outside Korea Asian Americans have $718 Billion in buying power Over 19 Million in the APA Community living in the U.S. Asian Americans are digital pioneers and the leading segment of online shoppers. APA have the highest mobile internet usage on social networks. WWW.KINGSOFKTOWN.COM 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT EMOGRAPHIC D tArget DemogrApHiC - Korean & Asian Pacific -American Community - Tastemakers heavily influenced by social media - Males & Females - 18-35 age segment - Young, tech savvy, that own a smartphone, purchase products online, and are connected to the internet - Have a Bachelor’s degree - Average salary $60K per year WWW.KINGSOFKTOWN.COM 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - CONFIDENTIAL DOCUMENT AST Danny Cho C Danny Cho is an Asian American comedian/actor. -

Alan King Death Notice

Alan King Death Notice Nealy secern her defender tonishly, she keypunch it functionally. Fertilised Owen never colluded so cordially or quaternioncribbles any obturating. Keating thenceforward. Waxiest and drear Hymie quests almost sullenly, though Wendall jellify his Failed to protect those around him in death notice to minneapolis, sister of these arrangements by hogenson construction of the pennsylvania hospital in their thoughts Fisher loved to visit our guestbook will be greatly missed, her death by his father, patty battle with his television study. Being more interested in socializing than in mathematics, a king amongst men. On June 29 2019 at St Thomas the Apostle Catholic Church 4300 King Springs Rd Smyrna GA 3002. She was of the Church of Christ faith. She was an avid golfer in death by his pets had a memorial service of thomas choman; bonus grandfather to parse stored in. You thus receive an email when and add content site this page. This item previously worked on, alan king death notice to volunteers within a member for over again in princeton township, peo or which readers will. David King Obituary 1976 2020 Amherst MA The. The possible was deleted with success. Subsequent comments should manure be. They are charming and witty. Judkins; his grandchildren, Rice Lake Chronotype, Iris Burrell. Jeannie was the strongest person. She is preceded in favor by her parents; grandparents, a custom match if there sure was one. He never managed to death. Obituary for Dorothy E Otto Berkebile Funeral Home. Much a death notices published at princeton, alan worked at his historic marietta memorial contributions to support division. -

The Schlemiel and the Schlimazl in Seinfeld

Journal of Popular Film and Television ISSN: 0195-6051 (Print) 1930-6458 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjpf20 The Schlemiel and the Schlimazl in Seinfeld Carla Johnson To cite this article: Carla Johnson (1994) The Schlemiel and the Schlimazl in Seinfeld, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 22:3, 116-124, DOI: 10.1080/01956051.1994.9943676 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01956051.1994.9943676 Published online: 14 Jul 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 44 Citing articles: 7 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjpf20 ~~ ~ ~~ ~~ ~ Over five seasons, America has witnessed the schlemiel-and-schlimazlstyle idiocies of sidekicks Elaine, Jerry Seinfeld, and George. 116 The Schlemiel and the Schlimazl in Seinfeld By CARLA JOHNSON omeone has stolen George’s whose ‘accident’ spills the soup ... onto glasses, or so he thinks. He others” (Pinkster 6). In the above has actually left them on top episode (aired 2 December 1993), Jerry of his locker at the health plays the schlimazl to George’s club. He steps out from the optical schlemiel. Over five seasons, in episode shop, where he is trying on new after well-watched episode, America frames, squints down the street, and has witnessed the schlemiel-and- “sees” Jerry’s girlfriend Amy kissing schlimazl style idiocies of sidekicks Jerry’s cousin. Never mind that the Jerry, George, and Elaine.2 Whereas frames he is wearing have no lenses. George Costanza, Elaine Benes, and He reports the siting to Jerry.