Severe Muscular Rigidity at Birth: Malignant Hyperthermia Syndrome?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion Sickness: Definition

Clinical and physiological characteristics of cybersickness Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Human Physiology) School of Biomedical Sciences and Pharmacy Faculty of Health and Medicine University of Newcastle, Australia This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that the work embodied in the thesis is my own work, conducted under normal supervision. The thesis contains no material which has been accepted, or is being examined, for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 and any approved embargo. Alireza Mazloumi Gavgani 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF AUTHORSHIP I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis contains published paper/s/scholarly work of which I am a joint author. I have included as part of the thesis a written declaration endorsed in writing by my supervisor, attesting to my contribution to the joint publication/s/scholarly work. Alireza Mazloumi Gavgani 3 STATEMENT OF COLLABORATION I hereby certify that some parts of the work embodied in this thesis have been done in collaboration with other researchers. I have included as part of the thesis a statement clearly outlining the extent of collaboration, with whom and under what auspices. -

Hypocalcemia Associated with Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis of the Newborn: Case Report and Literature Review Alphonsus N

case report Oman Medical Journal [2017], Vol. 32, No. 6: Hypocalcemia Associated with Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis of the Newborn: Case Report and Literature Review Alphonsus N. Onyiriuka 1* and Theodora E. Utomi2 1Endocrine and Metabolic Unit, Department of Child Health, University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria 2Special Care Baby Unit, Department of Nursing Services, St Philomena Catholic Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn (SCFNN) is a rare benign inflammatory Received: 4 November 2015 disorder of the adipose tissue but may be complicated by hypercalcemia or less frequently, Accepted: 21 October 2016 hypocalcemia, resulting in morbidity and mortality. Here we report the case of a neonate Online: with subcutaneous fat necrosis who surprisingly developed hypocalcemia instead DOI 10.5001/omj.2017.99 of hypercalcemia. A full-term female neonate was delivered by emergency cesarean section for fetal distress and was subsequently admitted to the Special Care Baby Keywords: Hypocalcemia; Infant, Unit. The mother’s pregnancy was uncomplicated up to delivery. Her anthropometric Newborn; Subcutaneous Fat measurements were birth weight 4.1 kg (95th percentile), length 50 cm (50th percentile), Necrosis; Perinatal Stress. and head circumference 34.5 cm (50th percentile). The Apgar scores were 2, 3, and 8 at 1, 5, 10 minutes, respectively. There was no abnormal facies and she was fed with breast milk only. On the seventh day of life, the infant was found to have multiple nodules located in the neck, upper back, and right arm. The nodules were firm, well circumscribed with no evidence of tenderness. -

N35.12 Postinfective Urethral Stricture, NEC, Female N35.811 Other

N35.12 Postinfective urethral stricture, NEC, female N35.811 Other urethral stricture, male, meatal N35.812 Other urethral bulbous stricture, male N35.813 Other membranous urethral stricture, male N35.814 Other anterior urethral stricture, male, anterior N35.816 Other urethral stricture, male, overlapping sites N35.819 Other urethral stricture, male, unspecified site N35.82 Other urethral stricture, female N35.911 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, meatal N35.912 Unspecified bulbous urethral stricture, male N35.913 Unspecified membranous urethral stricture, male N35.914 Unspecified anterior urethral stricture, male N35.916 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, overlapping sites N35.919 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, unspecified site N35.92 Unspecified urethral stricture, female N36.0 Urethral fistula N36.1 Urethral diverticulum N36.2 Urethral caruncle N36.41 Hypermobility of urethra N36.42 Intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) N36.43 Combined hypermobility of urethra and intrns sphincter defic N36.44 Muscular disorders of urethra N36.5 Urethral false passage N36.8 Other specified disorders of urethra N36.9 Urethral disorder, unspecified N37 Urethral disorders in diseases classified elsewhere N39.0 Urinary tract infection, site not specified N39.3 Stress incontinence (female) (male) N39.41 Urge incontinence N39.42 Incontinence without sensory awareness N39.43 Post-void dribbling N39.44 Nocturnal enuresis N39.45 Continuous leakage N39.46 Mixed incontinence N39.490 Overflow incontinence N39.491 Coital incontinence N39.492 Postural -

Disseminated Eosinophilic Infiltration of a Newborn Infant, with Perforation of the Terminal Ileum and Bile Duct Obstruction

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.56.1.66 on 1 January 1981. Downloaded from 66 Shinozaki, Saito, and Shiraki infant who acquired hepatitis from her mother. Br Med J 6 Yoshida A, Tozawa M, Furukawa N, Oya N, Kusunoki T, 1970; iv: 719-21. Kiyosawa N. HBsAg-positive chronic active hepatitis in 3 Bancroft W H, Warkel R L, Talbert A A, Russell P K. a 1 and 1/2 year-old-child (in Japanese). Shonika Shinryo Family with hepatitis-associated antigen. JAMA 1971; 1977;40: 1246-50. 217:1817-20. McCarthy J W. Hepatitis B antigen (HBAg)-positive chronic aggressive hepatitis and cirrhosis in an 8-month- Correspondence to Dr T Shinozaki, Department of old infant. A case report. JPediatr 1973; 83: 638-9. Paediatrics, Teikyo University School of Medicine, 11-1 5 Fujiwara T, Abe M, Tachi N, Jo M, Shiroda M. Kaga, 2 Chome, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo 173, Japan. HBsAg-positive infantile hepatitis associated with chronic aggressive hepatitis (in Japanese). Shonika Rinsho 1975; 28:1303-6. Received 26 November 1979 Disseminated eosinophilic infiltration of a newborn infant, with perforation of the terminal ileum and bile duct obstruction S M MURRAY AND C J WOODS Department ofPathology and Department ofPaediatrics, Victoria Hospital, Blackpool Case report SUMMARY A preterm boy died 4 days after delivery from septicaemia which at necropsy was found to be A white boy, weighing 1490 g, was born by spon- due to perforation of an eosinophilic lesion of the taneous vertex delivery at 35 weeks' gestation to a copyright. terminal ileum. -

A STUDY of RICKETS; Incidence in London

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.61.10.939 on 1 October 1986. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1986, 61, 939-940 A STUDY OF RICKETS; Incidence in London. BY DONALD PATERSON, M.B. (Edin.), M.R.C.P. (London), AND RUTH DARBY, M.B., Ch.B. (Birm.). (From the Infants' Hospital, Westminster.) In order to ascertain the incidence of rickets in London a study was attempted during the months of February, MIarch and April of 1925. It was thought that these being the darkest months of the year, following on a long, sunless period, the incidence of rickets would be at its height. Our fir-st difficulty was to define the basis upon which rickets could be diagnosed. We had over and over again diagnosed rickets clinically . Commentary copyright. J 0 FORFAR The Archives of Disease in Childhood, although it radiologically and 110 (32%) showed evidence of became the official journal of the British Paediatric previous rickets clinically, although radiologically Association (BPA), was first published two years the rickets was shown to have healed. No evidence before the founding of the BPA. Appropriately, the of rickets either clinically or radiologically was senior author of this paper on rickets, Dr Donald found in 225 (67%). Interestingly from a social point Paterson, played a leading part in the founding of of view, another paper in the same issue of the the BPA and was its first Secretary. He was a Archives (by Drs W P T Atkinson, Helen Mackay, http://adc.bmj.com/ Canadian who came to Edinburgh University to W L Kinnear, and H L Shaw) showed that children study medicine. -

Hyperthermia & Heat Stroke: Heat-Related Conditions

Hyperthermia & Heat Stroke: Heat-Related Conditions Joseph Rampulla, MS, APRN,BC eat-related conditions occur when excess heat taxes or overwhelms the body’s thermoregulatory mechanisms. Heat illness is preventable and occurs more Hcommonly than most clinicians realize. Heat illness most seriously affects the poor, urban-dwellers, young children, those with chronic physical and mental illnesses, substance abusers, the elderly, and people who engage in excessive physical The exposure to activity under harsh conditions. While considerable overlap occurs, the important the heat and the concrete during the syndromes are: heat stroke, heat exhaustion, and heat cramps. Heat stroke is a life- hot summer months places many rough threatening emergency and occurs when the loss of thermoregulatory control results sleepers at great risk in hyperpyrexia (very high fever) and severe damage to many internal organs. for heat stroke and hyperthermia. Photo by Epidemiology Sharon Morrison RN Heat illness is generally underreported, and the deaths than all other natural disasters combined in true incidence is unknown. Death rates from other the USA. The elderly, the very poor, and socially causes (e.g. cardiovascular, respiratory) increase isolated individuals are disproportionately affected during heat waves but are generally not reflected in by heat waves. For example, death records during the morbidity and mortality statistics related to heat heat waves invariably include many elders who died illness. Nonetheless, heat waves account for more alone in hot apartments. Age 65 years, chronic The Health Care of Homeless Persons - Part II - Hyperthermia and Heat Stroke 199 illness, and residence in a poor neighborhood are greater than 65. -

Sclerema Neonatorum Treated with Intravenous Immunoglobulin: a Case Report and Review of Treatments

Sclerema Neonatorum Treated With Intravenous Immunoglobulin: A Case Report and Review of Treatments Kesha J. Buster, MD; Holly N. Burford, MD; Faith A. Stewart, MD; Klaus Sellheyer, MD; Lauren C. Hughey, MD Practice Points Sclerema neonatorum is a rare neonatal panniculitis with a high mortality rate. Exchange transfusion improves survival, but its use in neonates has declined. Intravenous immunoglobulin represents a novel treatment option that may lead to increased survival in pre- term newborns with sclerema neonatorum. Sclerema neonatorum (SN)CUTIS is a rare neonatal improvement. Sclerema neonatorum remains a panniculitis that typically develops in severely poorly understood and difficult to treat neona- ill, preterm newborns within the first week of tal disorder. Although IVIG did not prevent our life and often is fatal. It usually occurs in pre- patient’s death, further studies are needed to term newborns with delivery complications such determine its clinical utility in the treatment of this as respiratory distress or maternal complica- rare disorder. tions such as eclampsia. Few clinical trials have Cutis. 2013;92:83-87. beenDo performed to address Notpotential treatments. Copy Successful treatment has been achieved via exchange transfusion (ET), but its use in neonates clerema neonatorum (SN) is a rare neonatal is declining. Similar to ET, intravenous immuno- panniculitis that typically develops in severely globulin (IVIG) enhances both humoral and Sill, preterm newborns within the first week cellular immunity and thus may decrease mor- of life. It is characterized by rapidly progressive tality associated with SN. We report a case of induration of subcutaneous fat. Treatments include SN in a term newborn who subsequently devel- supportive care, emollients, warming/maintaining oped septicemia. -

Hypothermia Hyperthermia Normothemic

Means normal body temperature. Normal body core temperature ranges from 99.7ºF to 99.5ºF. A fever is a Normothemic body temperature of 99.5 to 100.9ºF and above. Humans are warm-blooded mammals who maintain a constant body temperature (euthermia). Temperature regulation is controlled by the hypothalamus in the base of the brain. The hypothalamus functions as a thermostat for the body. Temperature receptors (thermoreceptors) are located in the skin, certain mucous membranes, and in the deeper tissues of the body. When an increase in body temperature is detected, the hypothalamus shuts off body mechanisms that generate heat (for example, shivering). When a decrease in body temperature is detected, the hypothalamus shuts off body mechanisms designed to cool the body (for example, sweating). The body continuously adjusts the metabolic rate in order to maintain a constant CORE Hypothermia Core body temperatures of 95ºF and lower is considered hypothermic can cause the heart and nervous system to begin to malfunction and can, in many instances, lead to severe heart, respiratory and other problems that can result in organ damage and death.Hannibal lost nearly half of his troops while crossing the Pyrenees Alps in 218 B.C. from hypothermia; and only 4,000 of Napoleon Bonaparte’s 100,000 men survived the march back from Russia in the winter of 1812 - most dying of starvation and hypothermia. During the sinking of the Titanic most people who entered the 28°F water died within 15–30 minutes. Symptoms: First Aid : Mild hypothermia: As the body temperature drops below 97°F there is Call 911 or emergency medical assistance. -

Malignant Hyperthermia.Pdf

Malignant Hyperthermia Matthew Alcusky PharmD, MS Student University of Rhode Island July, 2013 Financial Disclosure I have no financial obligations to disclose. Outline • Introduce malignant hyperthermia including its causes and implications • Describe the underlying pathophysiology • Detail the clinical presentation of MH • Summarize the necessary pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of MH • Highlight necessary considerations with the use of dantrolene • Discuss recrudescence Malignant Hyperthermia • A life threatening reaction that is most often triggered by the use of inhalational anesthetics • Estimated incidence of 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 100,000 anesthesia inductions • Early recognition and treatment is essential in reducing morbidity and mortality • Screening patients for past anesthesia history and family history, as well as conducting testing on at risk individuals is necessary to reduce MH occurrence Rosenberg H, Davis M, James D, Pollock N, Stowell K. Malignant hyperthermia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007 Apr 24;2:21. Review. Drugs Triggering Malignant Hyperthermia • Desflurane • Succinylcholine- • Enflurane only non-inhalational • Halothane anesthetic that triggers MH • Isoflurane • Nitrous Oxide- only • Methoxyflurane inhalational anesthetic • Sevoflurane that does not cause MH Hopkins PM. Malignant hyperthermia: pharmacology of triggering. Br J Anaesth. 2011 Jul;107(1):48-56. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer132. Epub 2011 May 30. Review. Pathophysiology • MH partially attributed to a dominant mutation in the ryanodine receptror 1 (RYR1) – Ryanodine receptors are activated by elevated Ca2+ levels, known as store overload induced calcium release (SOICR) – Mutant receptors are activated by lower Ca2+ levels – Volatile anesthetics further lower the SOICR threshold MacLennan DH, Chen SR. Store overload-induced Ca2mutations + release as a triggering mechanism for CPVT and MH episodes caused by in RYR and CASQ genes. -

Guidelines for Management of a Malignant Hyperthermia (MH) Crisis

Guidelines for the management of a Malignant Hyperthermia Crisis Successful treatment of a Malignant Hyperthermia (MH) crisis depends on early diagnosis and aggressive treatment. The onset of a reaction can be within minutes of induction or may be more insidious. Previous uneventful anaesthesia does not exclude MH. The steps below are intended as an aide memoire. Presentation may vary and treatment should be modified accordingly. Know where the dantrolene is stored in your theatre. Treatment can be optimised by teamwork. Call for help Diagnosis - consider MH if: 1 1. Unexplained, unexpected increase in end-tidal CO2 together with 2. Unexplained, unexpected tachycardia together with 3. Unexplained, unexpected increased in oxygen consumption Masseter muscle spasm, and especially more generalised muscle rigidity after suxamethonium, indicate a high risk of MH susceptibility but are usually self-limiting. Take measures to halt the MH process: 2 1. Remove trigger drugs, turn off vaporisers, use high fresh gas flows (oxygen), use a new, clean non-rebreathing circuit, hyperventilate. Maintain anaesthesia with intravenous agents such as propofol until surgery completed. 2. Dantrolene; give 2-3 mg.kg-1 i.v. initially and then 1 mg.kg-1 PRN. 3. Use active body cooling but avoid vasoconstriction. Convert active warming devices to active cooling, give cold 3 intravenous infusions, cold peritoneal lavage, extracorporeal heat exchange. Monitor: 4 ECG, SpO2, end-tidal CO2, invasive arterial BP, CVP, core and peripheral temperature, urine output and pH, arterial blood gases, potassium, haematocrit, platelets, clotting indices, creatine kinase (peaks at 12-24h). Treat the effects of MH: 5 1. Hypoxaemia and acidosis: 100% O2, hyperventilate, sodium bicarbonate. -

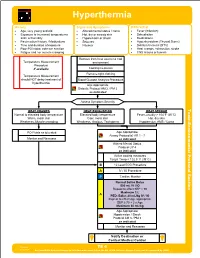

TE 04 Hyperthermia Protocol Final 2017 Editable.Pdf

Hyperthermia History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Age, very young and old • Altered mental status / coma • Fever (Infection) • Exposure to increased temperatures • Hot, dry or sweaty skin • Dehydration and / or humidity • Hypotension or shock • Medications • Past medical history / Medications • Seizures • Hyperthyroidism (Thyroid Storm) • Time and duration of exposure • Nausea • Delirium tremens (DT's) • Poor PO intake, extreme exertion • Heat cramps, exhaustion, stroke • Fatigue and / or muscle cramping • CNS lesions or tumors Remove from heat source to cool Temperature Measurement environment Procedure if available Cooling measures Remove tight clothing Temperature Measurement should NOT delay treatment of Blood Glucose Analysis Procedure hyperthermia Age Appropriate Diabetic Protocol AM 2 / PM 2 as indicated Assess Symptom Severity Toxic HEAT CRAMPS HEAT EXHAUSTION HEAT STROKE Normal to elevated body temperature Elevated body temperature Fever, usually > 104°F (40°C) Warm, moist skin Cool, moist skin Hot, dry skin - Weakness, Muscle cramping Weakness, Anxious, Tachypnea Hypotension, AMS / Coma Section Environmental Protocol PO Fluids as tolerated Age Appropriate Airway Protocol(s) AR 1 - 7 Monitor and Reassess as indicated Altered Mental Status Protocol UP 4 as indicated Active cooling measures Target Temp < 102.5° F (39°C) B 12 Lead ECG Procedure A IV / IO Procedure P Cardiac Monitor A Age Appropriate Hypotension / Shock Protocol AM 5 / PM 3 as indicated Monitor and Reassess Notify Destination or Contact Medical Control Revised TE 4 09/29/2017 Any local EMS System changes to this document must follow the NC OEMS Protocol Change Policy and be approved by OEMS Hyperthermia Toxic - Environmental Protocol Environmental Section Protocol Pearls • Recommended Exam: Mental Status, Skin, HEENT, Heart, Lungs, Neuro • Extremes of age are more prone to heat emergencies (i.e. -

How to Improve the Antioxidant Defense in Asphyxiated Newborns—Lessons from Animal Models

antioxidants Review How to Improve the Antioxidant Defense in Asphyxiated Newborns—Lessons from Animal Models Hanna Kletkiewicz 1 , Maciej Klimiuk 1, Alina Wo´zniak 2, Celestyna Mila-Kierzenkowska 2 , Karol Dokladny 3 and Justyna Rogalska 1,* 1 Department of Animal Physiology and Neurobiology, Faculty of Biological and Veterinary Sciences, Nicolaus Copernicus University, 87-100 Torun, Poland; [email protected] (H.K.); [email protected] (M.K.) 2 Department of Medical Biology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University, 87-100 Torun, Poland; [email protected] (A.W.); [email protected] (C.M.-K.) 3 Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-56-611-26-31 Received: 24 August 2020; Accepted: 15 September 2020; Published: 21 September 2020 Abstract: Oxygen free radicals have been implicated in brain damage after neonatal asphyxia. In the early phase of asphyxia/reoxygenation, changes in antioxidant enzyme activity play a pivotal role in switching on and off the cascade of events that can kill the neurons. Hypoxia/ischemia (H/I) forces the brain to activate endogenous mechanisms (e.g., antioxidant enzymes) to compensate for the lost or broken neural circuits. It is important to evaluate therapies to enhance the self-protective capacity of the brain. In animal models, decreased body temperature during neonatal asphyxia has been shown to increase cerebral antioxidant capacity. However, in preterm or severely asphyxiated newborns this therapy, rather than beneficial seems to be harmful. Thus, seeking new therapeutic approaches to prevent anoxia-induced complications is crucial.