Amnesia, Memory, and the Implicit/Explicit Learning Distinction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

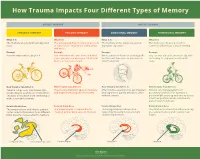

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

DO AMNESICS EXHIBIT COGNITIVE DISSONANCE REDUCTION? the Role of Explicit Memory and Attention in Attitude Change Matthew D

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Article DO AMNESICS EXHIBIT COGNITIVE DISSONANCE REDUCTION? The Role of Explicit Memory and Attention in Attitude Change Matthew D. Lieberman, Kevin N. Ochsner, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Daniel L. Schacter Harvard University Abstract—In two studies, we investigated the roles of explicit mem- CONSCIOUS CONTENT: THE ROLE OF ory and attentional resources in the process of behavior-induced atti- EXPLICIT MEMORY tude change. Although most theories of attitude change (cognitive Explicit memory refers to one’s ability to consciously recollect dissonance and self-perception theories) assume an important role for past events, behaviors, and experiences (Schacter, Chiu, & Ochsner, both mechanisms, we propose that behavior-induced attitude change 1993) and thus is a central component of most social abilities. Indeed, can be a relatively automatic process that does not require explicit people’s memory for the identities and actions of other people and memory for, or consciously controlled processing of, the discrepancy themselves forms the adhesive that gives them a continuing sense of between attitude and behavior. Using a free-choice paradigm, we place in their social world. Revising personal attitudes and beliefs in found that both amnesics and normal participants under cognitive response to a counterattitudinal behavior naturally seems to depend on load showed as much attitude change as did control participants. retrospective capacities. If Aesop’s forlorn lover of grapes could not remember that the grapes were out of reach, he would have no reason A fox saw some ripe black grapes hanging from a trellised vine. He resorted to to persuade himself of their reduced quality. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33). -

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W. D. Stevens, G. S. Wig, and D. L. Schacter, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ª 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 2.33.1 Introduction 623 2.33.2 Influences of Explicit Versus Implicit Memory 624 2.33.3 Top-Down Attentional Effects on Priming 626 2.33.3.1 Priming: Automatic/Independent of Attention? 626 2.33.3.2 Priming: Modulated by Attention 627 2.33.3.3 Neural Mechanisms of Top-Down Attentional Modulation 629 2.33.4 Specificity of Priming 630 2.33.4.1 Stimulus Specificity 630 2.33.4.2 Associative Specificity 632 2.33.4.3 Response Specificity 632 2.33.5 Priming-Related Increases in Neural Activation 634 2.33.5.1 Negative Priming 634 2.33.5.2 Familiar Versus Unfamiliar Stimuli 635 2.33.5.3 Sensitivity Versus Bias 636 2.33.6 Correlations between Behavioral and Neural Priming 637 2.33.7 Summary and Conclusions 640 References 641 2.33.1 Introduction stimulus that result from a previous encounter with the same or a related stimulus. Priming refers to an improvement or change in the When considering the link between behavioral identification, production, or classification of a stim- and neural priming, it is important to acknowledge ulus as a result of a prior encounter with the same or that functional neuroimaging relies on a number of a related stimulus (Tulving and Schacter, 1990). underlying assumptions. First, changes in informa- Cognitive and neuropsychological evidence indi- tion processing result in changes in neural activity cates that priming reflects the operation of implicit within brain regions subserving these processing or nonconscious processes that can be dissociated operations. -

Introduction to "Implicit Memory: Multiple Perspectives"

Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 1990. 28 (4). 338-340 Introduction to "Implicit memory: Multiple perspectives" DANIEL L. SCHACTER University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona Psychological studies of memory have traditionally assessed retention of recently acquired in formation with recall and recognition tests that require intentional recollection or explicit memory for a study episode. During the past decade, there has been a growing interest in the experimen tal study of implicit memory: unintentional retrieval of information on tests that do not require any conscious recollection of a specific previous experience. Dissociations between explicit and implicit memory have been established, but theoretical interpretation ofthem remains controver sial. The present set of papers examines implicit memory from multiple perspectives-cognitive, developmental, psychophysiological, and neuropsychological-and addresses key methodological, empirical, and theoretical issues in this rapidly growing sector of memory research. The papers that follow were presented at a symposium Delaney, 1990; Tulving & Schacter, 1990), it is also pos entitled "Implicit memory: Multiple perspectives," held sible to adopt a unitary or single-system view of memory at the annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society in At and still make use of the implicit/explicit distinction (e.g., lantaonNovember 17,1989. The symposium represents Roediger, Weldon, & Challis, 1989; Witherspoon & something of a milestone, in the sense that if someone Moscovitch, 1989). had suggested organizing an implicit memory symposium The distinction between implicit and explicit memory a decade ago, he or she probably would have been met is also closely related to the distinction between "direct" with a blank stare. That stare would have reflected two and "indirect" tests of memory (Johnson & Hasher, important facts: first, because the term "implicit 1987). -

The Three Amnesias

The Three Amnesias Russell M. Bauer, Ph.D. Department of Clinical and Health Psychology College of Public Health and Health Professions Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute University of Florida PO Box 100165 HSC Gainesville, FL 32610-0165 USA Bauer, R.M. (in press). The Three Amnesias. In J. Morgan and J.E. Ricker (Eds.), Textbook of Clinical Neuropsychology. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis/Psychology Press. The Three Amnesias - 2 During the past five decades, our understanding of memory and its disorders has increased dramatically. In 1950, very little was known about the localization of brain lesions causing amnesia. Despite a few clues in earlier literature, it came as a complete surprise in the early 1950’s that bilateral medial temporal resection caused amnesia. The importance of the thalamus in memory was hardly suspected until the 1970’s and the basal forebrain was an area virtually unknown to clinicians before the 1980’s. An animal model of the amnesic syndrome was not developed until the 1970’s. The famous case of Henry M. (H.M.), published by Scoville and Milner (1957), marked the beginning of what has been called the “golden age of memory”. Since that time, experimental analyses of amnesic patients, coupled with meticulous clinical description, pathological analysis, and, more recently, structural and functional imaging, has led to a clearer understanding of the nature and characteristics of the human amnesic syndrome. The amnesic syndrome does not affect all kinds of memory, and, conversely, memory disordered patients without full-blown amnesia (e.g., patients with frontal lesions) may have impairment in those cognitive processes that normally support remembering. -

Implicit Memory: How It Works and Why We Need It

Implicit Memory: How It Works and Why We Need It David W. L. Wu1 1University of British Columbia Correspondence to: [email protected] ABSTRACT Since the discovery that amnesiacs retained certain forms of unconscious learning and memory, implicit memory research has grown immensely over the past several decades. This review discusses two of the most intriguing questions in implicit memory research: how we think it works and why it is important to human behaviour. Using priming as an example, this paper surveys how historic behavioural studies have revealed how implicit memory differs from explicit memory. More recent neuroimaging studies are also discussed. These studies explore the neural correlate of priming and have led to the formation of the sharpening, fatigue, and facilitation neural models of priming. The latter part of this review discusses why humans have evolved with highly flexible explicit memory systems while still retaining inflexible implicit memory systems. Traditionally, researchers have regarded the competitive interaction between implicit and explicit memory systems to be fundamental for essential behaviours like habit learning. However, recently documented collaborative interactions suggest that both implicit and explicit processes are potentially necessary for optimal memory and learning performance. The literature reviewed in this paper reveals how implicit memory research has and continues to challenge our understanding of learning, memory, and the brain systems that underlie them. Keywords: implicit memory, priming, neural priming, habit learning INTRODUCTION several days despite having no recollection of the learning trials. For a time it was Not until Scoville and Milner believed that the acquisition of motor studied the amnesic patient H.M. -

Memory & Cognition

/ Memory & Cognition Volume 47 · Number 4 · May 2019 Special Issue: Recognizing Five Decades of Cumulative The role of control processes in temporal Progress in Understanding Human Memory and semantic contiguity and its Control Processes Inspired by Atkinson M.K. Healey · M.G. Uitvlugt 719 and Shiffrin (1968) Auditory distraction does more than disrupt rehearsal Guest Editors: Kenneth J. Malmberg· processes in children's serial recall Jeroen G. W. Raaijmakers ·Richard M. Shiffrin A.M. AuBuchon · C.l. McGill · E.M. Elliott 738 50 years of research sparked by Atkinson The effect of working memory maintenance and Shiffrin (1968) on long-term memory K.J. Malmberg · J.G.W. Raaijmakers · R.M. Shiffrin 561 J.K. Hartshorne· T. Makovski 749 · From ·short-term store to multicomponent working List-strength effects in older adults in recognition memory: The role of the modal model and free recall A.D. Baddeley · G.J. Hitch · R.J. Allen 575 L. Sahakyan 764 Central tendency representation and exemplar Verbal and spatial acquisition as a function of distributed matching in visual short-term memory practice and code-specific interference C. Dube 589 A.P. Young· A.F. Healy· M. Jones· L.E. Bourne Jr. 779 Item repetition and retrieval processes in cued recall: Dissociating visuo-spatial and verbal working memory: Analysis of recall-latency distributions It's all in the features Y. Jang · H. Lee 792 ~1 . Poirier· J.M. Yearsley · J. Saint-Aubin· C. Fortin· G. Gallant · D. Guitard 603 Testing the primary and convergent retrieval model of recall: Recall practice produces faster recall Interpolated retrieval effects on list isolation: success but also faster recall failure IndiYiduaLdifferences in working memory capacity W.J. -

Models of Memory

To be published in H. Pashler & D. Medin (Eds.), Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology, Third Edition, Volume 2: Memory and Cognitive Processes. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. MODELS OF MEMORY Jeroen G.W. Raaijmakers Richard M. Shiffrin University of Amsterdam Indiana University Introduction Sciences tend to evolve in a direction that introduces greater emphasis on formal theorizing. Psychology generally, and the study of memory in particular, have followed this prescription: The memory field has seen a continuing introduction of mathematical and formal computer simulation models, today reaching the point where modeling is an integral part of the field rather than an esoteric newcomer. Thus anything resembling a comprehensive treatment of memory models would in effect turn into a review of the field of memory research, and considerably exceed the scope of this chapter. We shall deal with this problem by covering selected approaches that introduce some of the main themes that have characterized model development. This selective coverage will emphasize our own work perhaps somewhat more than would have been the case for other authors, but we are far more familiar with our models than some of the alternatives, and we believe they provide good examples of the themes that we wish to highlight. The earliest attempts to apply mathematical modeling to memory probably date back to the late 19th century when pioneers such as Ebbinghaus and Thorndike started to collect empirical data on learning and memory. Given the obvious regularities of learning and forgetting curves, it is not surprising that the question was asked whether these regularities could be captured by mathematical functions. -

COGNITIVE REHABILITATION in a Severely Brain-Injured PATIENT with Amnesia, TETRAPLEGIA and ANARTHRIA

J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 393–396 CASE REPORT COMMUNICATING USING THE EYES WITHOUT REMEMBERING IT: COGNITIVE REHABILITATION IN A severely BRAIN-INJURED PATIENT WITH AMNESIA, TETRAPLEGIA AND ANARTHRIA Luigi Trojano, MD1,2, Pasquale Moretta, PsyD2 and Anna Estraneo, MD2 From the 1Neuropsychology Laboratory, Department of Psychology, Second University of Naples, Caserta and 2Salvatore Maugeri Foundation, IRCCS, Scientific Institute of Telese Terme (BN), Telese Terme, Italy We describe here a case of cognitive rehabilitation in a young LIS (4), but they nonetheless experience extreme difficulties patient with closed head injury, who had dense anterograde in communicating. For this reason patients with LIS can ac- amnesia and such disabling neurological defects (tetraplegia tively interact with the environment only by means of complex and anarthria) that the condition evoked some features of communicative systems, based for instance on brain-computer an incomplete locked-in syndrome. After a prolonged period interface devices (6). of no communicative possibility, the patient underwent a Patients with TBI with extremely severe motor disturbances specific training, based on principles of errorless learning, (tetraplegia and anarthria) face the same difficulties as patients with the aim of using a computerized eye-tracker system. with complete or incomplete LIS, but, in contrast to patients Although, due to memory disturbances, the patient always with LIS, they show the typical cognitive defects observed after denied ever having used the eye-tracker system, learned to a TBI. Therefore, any rehabilitative treatment in such patients use the computerized device and improved interaction with will be difficult and discouraging, even when it is aimed only the environment. -

Long Term Memory & Amnesia

Previous theories of Amnesia: encoding faliure (consolidation) rapid forgetting and Amnesic Patients typically retain old procedural retrieval failure (retroactive/proactive information and are reasonably good at learning interference, Underwood; McGeoch) new procedural skills (H.M and mirror writing) Important Current Theory: Contextual Amnesia & the Brain Linked to Conditioning: eyeblink with puf of air leads to Memory Theory (Ryan et al. 2000) medial temporal lobe and diencephalic conditioned response. Patients with amnesia impairment in integrating of binding region, including mamillary bodies and typically acquire this. contextual/relational features of memory. thalamus. Priming: Improvement or bias in performance The medial temporal lobe and hippocampus resulting from prior, supraliminal presentation of Procedural Memory are proposed to bind events to the contexts stimuli. Tulving et al. (1982) primed participants Often relatively automatic processes in which they occur. This bypasses the with a list of words and then showed them letters (requiring little attention) allowing for declarative vs procedural distinction. And (cued-recall). Recall was better for words behavioural responses to there is reasonable support for this theory presented earlier. Amnesic patients are relatively environmental cues. (Channon, Shanks et al 2006.) normal on these tasks. Long-Term Memory & Amnesia Temporary storage of information with rapid Short-Term Memory decay and sensitivity to interference. Supported by studies of recency efect (Murdock, Postman), which is taken as evidence of short Long-Term Memory Mediates declarative Double Dissociation?! but not non-declarative (procedural) memory. term memory store. Also by studies supporting subvocal speech (Baddeley, 1966) However, studies have provided evidence of Declarative Memory This is knowledge STM link with LTM retrieved by explicit, deliberate recollection.