The Mohican Connection1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mashantucket Pequot Tribe V. Town of Ledyard: the Preemption of State Taxes Under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2014 Mashantucket Pequot Tribe v. Town of Ledyard: The Preemption of State Taxes under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment Edward A. Lowe Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Recommended Citation Lowe, Edward A., "Mashantucket Pequot Tribe v. Town of Ledyard: The Preemption of State Taxes under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment" (2014). Connecticut Law Review. 267. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/267 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 47 NOVEMBER 2014 NUMBER 1 Comment MASHANTUCKET PEQUOT TRIBE V. TOWN OF LEDYARD: THE PREEMPTION OF STATE TAXES UNDER BRACKER, THE INDIAN TRADER STATUTES, AND THE INDIAN GAMING REGULATORY ACT EDWARD A. LOWE The Indian Tribes of the United States occupy an often ambiguous place in our legal system, and nowhere is that ambiguity more pronounced than in the realm of state taxation. States are, for the most part, preempted from taxing the Indian Tribes, but something unique happens when the state attempts to levy a tax on non-Indian vendors employed by a Tribe for work on a reservation. The state certainly has a significant justification for imposing its tax on non-Indians, but at what point does the non-Indian vendor’s relationship with the Tribe impede the state’s right to tax? What happens when the taxed activity is a sale to the Tribe? And what does it mean when the taxed activity has connections to Indian Gaming? This Comment explores three preemption standards as they were interpreted by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in a case between the State of Connecticut and the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe. -

The Decline of Algonquian Tongues and the Challenge of Indian Identity in Southern New England

Losing the Language: The Decline of Algonquian Tongues and the Challenge of Indian Identity in Southern New England DA YID J. SIL VERMAN Princeton University In the late nineteenth century, a botanist named Edward S. Burgess visited the Indian community of Gay Head, Martha's Vineyard to interview native elders about their memories and thus "to preserve such traditions in relation to their locality." Among many colorful stories he recorded, several were about august Indians who on rare, long -since passed occasions would whisper to one another in the Massachusett language, a tongue that younger people could not interpret. Most poignant were accounts about the last minister to use Massachusett in the Gay Head Baptist Church. "While he went on preaching in Indian," Burgess was told, "there were but few of them could know what he meant. Sometimes he would preach in English. Then if he wanted to say something that was not for all to hear, he would talk to them very solemnly in the Indian tongue, and they would cry and he would cry." That so few understood what the minister said was reason enough for the tears. "He was asked why he preached in the Indian language, and he replied: 'Why to keep up my nation.' " 1 Clearly New England natives felt the decline of their ancestral lan guages intensely, and yet Burgess never asked how they became solely English speakers. Nor have modem scholars addressed this problem at any length. Nevertheless, investigating the process and impact of Algonquian language loss is essential for a fuller understanding Indian life during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and even beyond. -

Hudson Valley Community College

A.VII.4 Articulation Agreement: Hudson Valley Community College (HVCC) to College of Staten Island (CSI) Associate in Science in Business Administration (HVCC) to Bachelor of Science: International Business Concentration (CSI) THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ARTICULATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND A. SENDING AND RECEIVING INSTITUTIONS Sending Institution: Hudson Valley Community College Department: Program: School of Business and Liberal Arts Business Administration Degree: Associate in Science (AS) Receiving Institution: College of Staten Island Department: Program: Lucille and Jay Chazanoff School of Business Business: International Business Concentration Degree: Bachelor of Science (BS) B. ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS FOR SENIOR COLLEGE PROGRAM Minimum GPA- 2.5 To gain admission to the College of Staten Island, students must be skill certified, meaning: • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in a credit-bearing mathematics course of at least 3 credits • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in freshmen composition, its equivalent, or a higher-level English course Total transfer credits granted toward the baccalaureate degree: 63-64 credits Total additional credits required at the senior college to complete baccalaureate degree: 56-57 credits 1 C. COURSE-TO-COURSE EQUIVALENCIES AND TRANSFER CREDIT AWARDED HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND Credits Course Number & Title Credits Course Number & Title Credits Awarded CORE RE9 UIREM EN TS: ACTG 110 Financial Accounting 4 -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Harvest Ceremony

ATLANTIC OCEAN PA\\' fl.. Xf I I' I \ f 0 H I PI \ \. I \I ION •,, .._ "', Ll ; ~· • 4 .. O\\'\\1S s-'' f1r~~' ~, -~J.!!!I • .. .I . _f' .~h\ ,. \ l.J rth..i'i., \ inc-v •.u d .. .. .... Harvest Ceremony BEYOND THE THANK~GIVING MYTH - a study guide Harvest Ceremony BEYOND THE THANKSGIVING MYTH Summary: Native American people who first encountered the “pilgrims” at what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts play a major role in the imagination of American people today. Contemporary celebrations of the Thanksgiving holiday focus on the idea that the “first Thanksgiving” was a friendly gathering of two disparate groups—or even neighbors—who shared a meal and lived harmoniously. In actuality, the assembly of these people had much more to do with political alliances, diplomacy, and an effort at rarely achieved, temporary peaceful coexistence. Although Native American people have always given thanks for the world around them, the Thanksgiving celebrated today is more a combination of Puritan religious practices and the European festival called Harvest Home, which then grew to encompass Native foods. The First People families, but a woman could inherit the position if there was no male heir. A sachem could be usurped by In 1620, the area from Narragansett Bay someone belonging to a sachem family who was able in eastern Rhode Island to the Atlantic Ocean in to garner the allegiance of enough people. An unjust or southeastern Massachusetts, including Cape Cod, unwise sachem could find himself with no one to lead, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, was the home as sachems had no authority to force the people to do of the Wampanoag. -

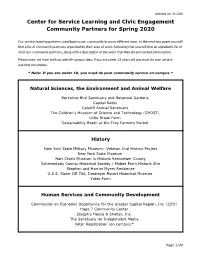

Center for Service Learning and Civic Engagement Community Partners for Spring 2020

Updated Jan 16 2020 Center for Service Learning and Civic Engagement Community Partners for Spring 2020 Our service learning partners contribute to our community in many different ways. In the next two pages you will find a list of community partners organized by their area of work. Following that you will find an alphabetic list of all of our community partners, along with a description of the work that they do and contact information. Please note, we have both on and off-campus sites. If you are under 18 years old you must do your service learning on campus. * Note: If you are under 18, you must do your community service on-campus * Natural Sciences, the Environment and Animal Welfare Berkshire Bird Sanctuary and Botanical Gardens Capital Roots Catskill Animal Sanctuary The Children’s Museum of Science and Technology (CMOST) Little Brook Farm Sustainability Booth at the Troy Farmers Market History New York State Military Museum– Veteran Oral History Project New York State Museum Hart Cluett Museum in Historic Rensselaer County Schenectady County Historical Society / Mabee Farm Historic Site Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence U.S.S. Slater DE 766, Destroyer Escort Historical Museum Yates Farm Human Services and Community Development Commission on Economic Opportunity for the Greater Capital Region, Inc. (CEO) Hope 7 Community Center Joseph’s House & Shelter, Inc. The Sanctuary for Independent Media Voter Registration (on campus)* Page 1/20 Updated Jan 16 2020 Literacy and adult education English Conversation Partners Program (on campus)* Learning Assistance Center (on campus)* Literacy Volunteers of Rensselaer County The RED Bookshelf Daycare, school and after-school programs, children’s activities Albany Free School Albany Police Athletic League (PAL), Inc. -

The Tribal Warriors; and the Powwows, Who Were Wise Men and Shamans

63 A TRIPARTITE POLITICAL SYSTEM AMONG CHRISTIAN INDIANS OF EARLY MASSACHUSETTS Susan L. MacCulloch University of California, Berkeley In seventeenth century colonial Massachusetts there existed for a brief but memorable period about twenty towns of various size and success inhabited entirely by Christian Indians. These towns of converts were islands in a sea of opposing currents, for unconverted Indians scorned them, and un- trusting English opposed them. The towns and their inception is a story in itself (see Harvey [MacCulloch] 1965:M.A. thesis); but it will suffice here to note that in the established Indian towns the inhabitants dressed in English clothes, were learning or already practicing their "callings" or trades, and were earnest Puritan churchgoers. They were able to read and write in Indian (and some in English), took logic and theology courses from Rev. John Eliot in the summer, and sent their promising young men to the Indian College at Harvard. Furthermore, they had extensive farmed land, live- stock, and orchards, and participated in a market economy with the somewhat incredulous colonists. The picture, in short, was not the one usually de- scribed in grammar school history books of the red savage faced by the colonists. One of the most interesting aspects of the Praying Towns, as they were called, was their unique political system, made up of the English colonial and the traditional tribal systems; and superimposed on both of these was a biblical arrangement straight out of Moses. In order to fully appreciate this tripartite political system some background information about the native and colonial systems is helpful. -

Vol. 09 Mohegan-Pequot

Ducksunne, he falls down (dû´ksûnî´), perhaps cogn. with N. nu´kshean it falls down. Cf. Abn. pagessin it falls, said of a thunderbolt. Duckwong, mortar (dûkwâ´ng) = N. togguhwonk; RW. tácunuk; Abn. tagwaôgan; D. tachquahoakan, all from AMERICAN LANGUAGE the stem seen in N. togkau he pounds. See REPRINTS teecommewaas. Dunker tei, what ails you? (dûn kêtîâ´î). Dûn = Abn. tôni what; ke is the 2d pers.; t is the infix before a stem beginning with a vowel, and îâ´î is the verb ‘to be.’ Cf. Abn. tôni k-dâyin? ‘how are you,’ or ‘where are you?’ VOL. 9 Dupkwoh, night, dark (dû´pkwû) = Abn. tebokw. Loc. of dû´pkwû is dû´pkwûg. Een, pl. eenug, man (în, î´nûg) = N. ninnu, seen also in Abn. -winno, only in endings. Cf. Ojibwe inini. Trumbull says, in ND. 292, that N. ninnu emphasizes the 3d pers., and through it the 1st pers. Thus, noh, neen, n’un ‘he is such as this one’ or ‘as I am.’ Ninnu was used only when speaking of men of the Indian race. Missinûwog meant men of other races. See skeedumbork. Ewo, ewash, he says, say it; imv. (î´wó, î´wâs&). This con- tains the same stem as Abn. i-dam he says it. Cf. also RW. teagua nteawem what shall I say? In Peq. nê-îwó = I say, without the infixed -t. Gawgwan, see chawgwan. Ge, ger, you (ge). This is a common Algonquian heritage. 22 Chunche, must (chû´nchî) = Abn. achowi. This is not in N., where mos = must (see mus). -

Upper Hudson Basin

UPPER HUDSON BASIN Description of the Basin The Upper Hudson Basin is the largest in New York State (NYS) in terms of size, covering all or part of 20 counties and about 7.5 million acres (11,700 square miles) from central Essex County in the northeastern part of the State, southwest to central Oneida County in north central NYS, southeast down the Hudson River corridor to the State’s eastern border, and finally terminating in Orange and Putnam Counties. The Basin includes four major hydrologic units: the Upper Hudson, the Mohawk Valley, the Lower Hudson, and the Housatonic. There are about 23,000 miles of mapped rivers and streams in this Basin (USGS Watershed Index). Major water bodies include Ashokan Reservoir, Esopus Creek, Rondout Creek, and Wallkill River (Ulster and Orange Counties) in the southern part of the Basin, Schoharie Creek (Montgomery, Greene, and Schoharie Counties) and the Mohawk River (from Oneida County to the Hudson River) in the central part of the Basin, and Great Sacandaga Lake (Fulton and Saratoga Counties), Saratoga Lake (Saratoga County), and Schroon Lake (Warren and Essex Counties) in the northern part of the Basin. This region also contains many smaller lakes, ponds, creeks, and streams encompassing thousands of acres of lentic and lotic habitat. And, of course, the landscape is dominated by one of the most culturally, economically, and ecologically important water bodies in the State of New York - the Hudson River. For hundreds of years the Hudson River has helped bolster New York State’s economy by sustaining a robust commercial fishery, by providing high value residential and commercial development, and by acting as a critical transportation link between upstate New York/New England and the ports of New York City. -

Episodes from a Hudson River Town Peak of the Catskills, Ulster County’S 4,200-Foot Slide Mountain, May Have Poked up out of the Frozen Terrain

1 Prehistoric Times Our Landscape and First People The countryside along the Hudson River and throughout Greene County always has been a lure for settlers and speculators. Newcomers and longtime residents find the waterway, its tributaries, the Catskills, and our hills and valleys a primary reason for living and enjoying life here. New Baltimore and its surroundings were formed and massaged by the dynamic forces of nature, the result of ongoing geologic events over millions of years.1 The most prominent geographic features in the region came into being during what geologists called the Paleozoic era, nearly 550 million years ago. It was a time when continents collided and parted, causing upheavals that pushed vast land masses into hills and mountains and complementing lowlands. The Kalkberg, the spiny ridge running through New Baltimore, is named for one of the rock layers formed in ancient times. Immense seas covered much of New York and served as collect- ing pools for sediments that consolidated into today’s rock formations. The only animals around were simple forms of jellyfish, sponges, and arthropods with their characteristic jointed legs and exoskeletons, like grasshoppers and beetles. The next integral formation event happened 1.6 million years ago during the Pleistocene epoch when the Laurentide ice mass developed in Canada. This continental glacier grew unyieldingly, expanding south- ward and retreating several times, radically altering the landscape time and again as it traveled. Greene County was buried. Only the highest 5 © 2011 State University of New York Press, Albany 6 / Episodes from a Hudson River Town peak of the Catskills, Ulster County’s 4,200-foot Slide Mountain, may have poked up out of the frozen terrain. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

CERTIFIED HOME HEALTH AGENCY DIRECTORY (Excluding Special Needs Populations Chhas) AGENCY NAME and ADDRESS COUNTIES SERVED

CERTIFIED HOME HEALTH AGENCY DIRECTORY (excluding Special Needs Populations CHHAs) AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS COUNTIES SERVED ALBANY AT HOME CARE INC DELAWARE HERKIMER OTSEGO 25 ELM STREET CHENANGO SCHOHARIE ONEONTA, NEW YORK 13820 3824601 (607) 432-7924 F: (607) 432-5836 337233 www.ahcnys.org COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTER OF ST MARY'S FULTON WARREN HEALTHCARE & NATHAN LITTAUER HOSPITAL, MONTGOMERY HAMILTON 2-8 WEST MAIN ST HERKIMER SARATOGA JOHNSTOWN, NY 12095-2308 1758601 SCHOHARIE (518) 762-8215 F: (518) 762-4109 337205 www.chchomecare.org EDDY VISITING NURSE ASSOCIATION ALBANY COLUMBIA GREENE 433 RIVER ST STE 3000 RENSSELAER SARATOGA TROY, NY 12180-2260 4102601 SCHENECTADY (518) 274-6200 F: (518) 274-2908 337203 wwww.sphp.com ESSEX COUNTY NURSING SERVICE ESSEX 132 WATER ST, PO BOX 217 ELIZABETHTOWN, NY 12932-0217 1521600 (518) 873-3500 F: (518) 873-3539 337118 www.co.essex.ny.us FORT HUDSON CERTIFIED HOME HEALTH WARREN AGENCY, INC. WASHINGTON 319 BROADWAY FORT EDWARD, NEW YORK 12828 5724600 -1221 (518) 747-9019 F: (518) 681-3071 337445 FRANKLIN COUNTY PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES FRANKLIN 355 WEST MAIN STREET, SUITE 425 MALONE, NEW YORK 12953 1624600 (518) 481-1710 F: (518) 483-9378 337086 franklincony.org/content HAMILTON COUNTY PUBLIC HEALTH NURSING HAMILTON SERVICE HOME HEALTH AGENCY PO BOX 250 139 WHITE BIRCH LANE INDIAN LAKE, NY 12842-0250 2055601 (518) 648-6141 F: (518) 648-6143 337173 www.hamiltoncountypublichealth.org 01/19/2017 Page 1 of 19 AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS COUNTIES SERVED HCR / HCR HOME CARE DELAWARE 5 1/2 MAIN STREET, SUITE 4 DELHI, NY 13753 1257602 (607) 464-4010 F: (607) 464-4041 337174 www.hcrhealth.com HCR / HCR HOME CARE WASHINGTON 124 MAIN STREET, SUITE 201 HUDSON FALLS, NY 12839-1829 5726601 (518) 636-5726 F: (518) 636-5727 337023 www.hcrhealth.com HCR / HCR HOME CARE SCHOHARIE OTSEGO 297 MAIN STREET ONEONTA, NEW YORK 13820 4724601 (518) 254-7092 F: (518) 823-4006 337083 www.hcrhealth.com.