A Grammar of the Nipmuck Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mashantucket Pequot Tribe V. Town of Ledyard: the Preemption of State Taxes Under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2014 Mashantucket Pequot Tribe v. Town of Ledyard: The Preemption of State Taxes under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment Edward A. Lowe Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Recommended Citation Lowe, Edward A., "Mashantucket Pequot Tribe v. Town of Ledyard: The Preemption of State Taxes under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment" (2014). Connecticut Law Review. 267. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/267 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 47 NOVEMBER 2014 NUMBER 1 Comment MASHANTUCKET PEQUOT TRIBE V. TOWN OF LEDYARD: THE PREEMPTION OF STATE TAXES UNDER BRACKER, THE INDIAN TRADER STATUTES, AND THE INDIAN GAMING REGULATORY ACT EDWARD A. LOWE The Indian Tribes of the United States occupy an often ambiguous place in our legal system, and nowhere is that ambiguity more pronounced than in the realm of state taxation. States are, for the most part, preempted from taxing the Indian Tribes, but something unique happens when the state attempts to levy a tax on non-Indian vendors employed by a Tribe for work on a reservation. The state certainly has a significant justification for imposing its tax on non-Indians, but at what point does the non-Indian vendor’s relationship with the Tribe impede the state’s right to tax? What happens when the taxed activity is a sale to the Tribe? And what does it mean when the taxed activity has connections to Indian Gaming? This Comment explores three preemption standards as they were interpreted by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in a case between the State of Connecticut and the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Vol. 09 Mohegan-Pequot

Ducksunne, he falls down (dû´ksûnî´), perhaps cogn. with N. nu´kshean it falls down. Cf. Abn. pagessin it falls, said of a thunderbolt. Duckwong, mortar (dûkwâ´ng) = N. togguhwonk; RW. tácunuk; Abn. tagwaôgan; D. tachquahoakan, all from AMERICAN LANGUAGE the stem seen in N. togkau he pounds. See REPRINTS teecommewaas. Dunker tei, what ails you? (dûn kêtîâ´î). Dûn = Abn. tôni what; ke is the 2d pers.; t is the infix before a stem beginning with a vowel, and îâ´î is the verb ‘to be.’ Cf. Abn. tôni k-dâyin? ‘how are you,’ or ‘where are you?’ VOL. 9 Dupkwoh, night, dark (dû´pkwû) = Abn. tebokw. Loc. of dû´pkwû is dû´pkwûg. Een, pl. eenug, man (în, î´nûg) = N. ninnu, seen also in Abn. -winno, only in endings. Cf. Ojibwe inini. Trumbull says, in ND. 292, that N. ninnu emphasizes the 3d pers., and through it the 1st pers. Thus, noh, neen, n’un ‘he is such as this one’ or ‘as I am.’ Ninnu was used only when speaking of men of the Indian race. Missinûwog meant men of other races. See skeedumbork. Ewo, ewash, he says, say it; imv. (î´wó, î´wâs&). This con- tains the same stem as Abn. i-dam he says it. Cf. also RW. teagua nteawem what shall I say? In Peq. nê-îwó = I say, without the infixed -t. Gawgwan, see chawgwan. Ge, ger, you (ge). This is a common Algonquian heritage. 22 Chunche, must (chû´nchî) = Abn. achowi. This is not in N., where mos = must (see mus). -

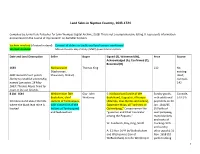

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. -

NATIVE AMERICANS in MASSACHUSETTS: NEW HOMECOMINGS and ONGOING DISPLACEMENTS by J

NATIVE AMERICANS IN MASSACHUSETTS: NEW HOMECOMINGS AND ONGOING DISPLACEMENTS By J. Cedric Woods, Director, Institute for New England Native American Studies, UMass Boston hat is now the Commonwealth of For these people, catastrophic population loss followed Massachusetts, was, is and always will sustained contact with Europeans due to disease, Wbe Indian Country. The names used enslavement and warfare, but nevertheless Native for the inhabitants and settlements of this land have Peoples are still very much present in Massachusetts. changed over the last 10,000 years, but thousands of The trends of loss and survival would continue, Indigenous Peoples from the Massachusett, Nipmuc although punctuated by periods of stabilization, and Wampanoag tribes historically resided in the areas throughout much of the 17th century. The 18th century on which this section focuses: the town of Aquinnah brought new challenges as the ongoing entanglement on Martha’s Vineyard (what Natives call Noepe) and of Natives in European, and later American, military the Greater Boston region (Figure 4.1). conflicts and physically dangerous employment (like FIGURE 4.1 Several distinct Native Peoples inhabited what is now Massachusetts and points south. Tribal territories of Southern New England. Around 1600. Author: Nikater, adapted to English by Hydrargyrum. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tribal_Territories_Southern_New_England.png#/media/File:Tribal_Territories_ Southern_New_England.png 41 NATIVE AMERICANS IN MASSACHUSETTS whaling) led to chronically disproportionate loss For those unfamiliar with ongoing trends in Indian of life, particularly of Native men (Figure 4.2). The Country demographics, a look at the most commonly 19th century saw efforts by the Commonwealth to used Census data for the Massachusetts Native politically dismantle Native communities (whether population may be deceiving. -

The Easton Family of Southeast Massachusetts: the Dynamics Surrounding Five Generations of Human Rights Activism 1753--1935

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935 George R. Price The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Price, George R., "The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9598. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: Date: 7 — 2 ~ (p ~ O b Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

The Mohegan Tribal Government the Mohegan Tribe Is a Sovereign

The Mohegan Tribal Government The Mohegan Tribe is a sovereign, federally recognized Indian nation. Its reservation is located on the Thames River near Uncasville, Connecticut. The Mohegan Nation exercises full civil jurisdiction and concurrent criminal jurisdiction over its lands. The Tribe is governed by a Tribal Constitution, which empowers a nine-member Tribal Council to serve as both the legislative and executive branch, and a seven-member Council of Elders which is responsible for judicial oversight and cultural integrity. The Chairman of the Tribal Council, currently Kevin Brown “Red Eagle,” serves as Chief Executive of the Tribe. The Tribal Council and Council of Elders serve four year, staggered terms. A Tribal Court system exists to adjudicate constitutional as well as civil issues. Other Tribal leaders include Chief Lynn “Mutáwi Mutáhash” (Many Hearts) Malerba, Medicine Woman and Tribal Historian Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel, Pipe Carriers Bruce “Two Dogs” Bozsum and Christopher Harris “Painted Turtle,” Firekeeper Jay Ihloff “Two Trees,” and Lodgekeeper Charlie Strickland “Two Bears.” The Tribal Government has numerous administrative departments, including Cultural and Community Programs, Education, Library and Archives, Gaming Commission, Health and Human Services, Housing Authority, Public Safety, Utility Authority, Land Preservation and Planning and Environmental Protection. Current enrollment of the Tribe stands at approximately 2,100 individuals, most of whom reside in Connecticut near ancestral Tribal lands. Tribal Government 2017 Page 1 of 2 Current Tribal Council Members: Kevin Brown "Red Eagle," Chairman James Gessner Jr., Vice Chairman Cheryl A. Todd, Recording Secretary Kathy Regan-Pyne, Corresponding Secretary Thayne D. Hutchins Jr., Treasurer Mark F. Brown, Ambassador William Quidgeon, Jr., Councilor Joseph William Smith, Councilor Sarah E. -

King Philip's Ghost: Race War and Remembrance in the Nashoba Regional School

King Philip’s Ghost: Race War and Remembrance in the Nashoba Regional School District By Timothy H. Castner 1 The gruesome image still has the power to shock. A grim reminder of what Thoreau termed the Dark Age of New England. The human head was impaled upon a pole and raised high above Plymouth. The townspeople had been meeting for a solemn Thanksgiving filled with prayers and sermons, celebrating the end of the most brutal and genocidal war in American history. The arrival and raising of the skull marked a symbolic high point of the festivities. Many years later the great Puritan minister, Cotton Mather, visited the site and removed the jaw bone from the then exposed skull, symbolically silencing the voice of a person long dead and dismembered. There the skull remained for decades, perhaps as long as forty years as suggested by historian Jill Lepore. Yet while his mortal remains went the way of all flesh, Metacom or King Philip, refused to be silenced. He haunts our landscape, our memories and our self-conception. How might we choose to live or remember differently if we paused to learn and listen? For Missing Image go to http://www.telegram.com/apps/pbcsi.dll/bilde?NewTbl=1&Site=WT&Date=20130623&Category=COULTER02&Art No=623009999&Ref=PH&Item=75&Maxw=590&Maxh=450 In June of 2013 residents of Bolton and members of the Nashoba Regional School District had two opportunities to ponder the question of the Native American heritage of the area. On June 9th at the Nashoba Regional Graduation Ceremony, Bolton resident and Nashoba Valedictorian, Alex Ablavsky questioned the continued use of the Chieftain and associated imagery, claiming that it was a disrespectful appropriation of another groups iconography which tarnished his experience at Nashoba. -

Shekomeko: the Mohican Village That Shaped the Moravian Missionary World

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2019 Shekomeko: The Mohican Village that Shaped the Moravian Missionary World Samuel J. Dickson Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2019 Part of the History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Dickson, Samuel J., "Shekomeko: The Mohican Village that Shaped the Moravian Missionary World" (2019). Senior Projects Spring 2019. 205. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2019/205 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shekomeko: The Mohican Village that Shaped the Moravian Missionary World Senior Project submitted to The Division of Social Studies Of Bard College By Samuel Joseph Dickson Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Senior Project Advisor, Christian Crouch for helping to encapsulate and solidify the threads that would eventually become my senior project, as well as all the 4:30 meetings every Monday after work. Without Chris Lindner's Archeology class, and reading Otterness’s Becoming German: the 1709 Palatine Migration to New York, this project would have never happened. -

To Download a PDF of an Interview with Ray

The Resort Entertainment Business An Interview with Ray Pineault, President and General Manager, Mohegan Sun Mohegan Sun Casino entrance (left); Earth Tower and Sky Tower (above) EDITORS’ NOTE Ray Pineault We’ve always known that the a short time; New York has expanded with Resorts has been with the Mohegan Tribe resort entertainment business we’re in and a few others recently; and Twin Rivers is and Mohegan Sun since March is highly competitive and highly capi- looking to add a casino in Rhode Island. 2001. He served as a Senior Staff tal intensive. We have many repeat What we’re still offering is that high-level Attorney for the Tribe. In addition, guests, so it’s always important to be guest experience. We help guests understand Pineault has provided legal services providing them with the newest and why they should choose us and drive from to several of the Mohegan Tribe’s best entertainment options, and Massachusetts or New York because they will departments and entities, as well we have to stay ahead of the game. have a special feeling and experience. We know as Little People, LLC and Crow Hill The council and management here that guests are willing to make that time for a Properties. Pineault also served as have always been forward-thinking brand they’re loyal to. a management board member of and forward-looking in providing Is there a profile for the Mohegan Sun Mohegan Information Technology new and upgraded opportunities, and guest? Group, LLC. He holds a Bachelor of Ray Pineault better entertainment for our guests. -

Glossary of the Mohegan-Pequot Language Author(S): J

Glossary of the Mohegan-Pequot Language Author(s): J. Dyneley Prince and Frank G. Speck Source: American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1904), pp. 18-45 Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/659295 . Accessed: 20/02/2014 04:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Anthropologist. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 194.94.96.194 on Thu, 20 Feb 2014 04:14:47 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions GLOSSARY OF THE MOHEGAN-PEQUOT LANGUAGE BY J. DYNELEY PRINCE ANDFRANK G. SPECK There is always something strangely pathetic about a dying language, especially when, like the Mohegan-Pequot idiom, the dialect exists in the memory of but a single living person. Mr Speck has obtained two connected texts and most of the following words and forms from Mrs Fidelia A. H. Fielding, an aged Indian woman resident at Mohegan, near Norwich, Conn., who has kept up her scanty knowledge of her early speech chiefly by talking to herself.