Native Diaspora and New Communities: Algonkian and WÃ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference Native Land Acknowledgement

2021 Massachusetts & Rhode Island Land Conservation Conference Land Acknowledgement It is important that we as a land conservation community acknowledge and reflect on the fact that we endeavor to conserve and steward lands that were forcibly taken from Native people. Indigenous tribes, nations, and communities were responsible stewards of the area we now call Massachusetts and Rhode Island for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, and Native people continue to live here and engage in land and water stewardship as they have for generations. Many non-Native people are unaware of the indigenous peoples whose traditional lands we occupy due to centuries of systematic erasure. I am participating today from the lands of the Pawtucket and Massachusett people. On the screen I’m sharing a map and alphabetical list – courtesy of Native Land Digital – of the homelands of the tribes with territories overlapping Massachusetts and Rhode Island. We encourage you to visit their website to access this searchable map to learn more about the Indigenous peoples whose land you are on. Especially in a movement that is committed to protection, stewardship and restoration of natural resources, it is critical that our actions don’t stop with mere acknowledgement. White conservationists like myself are really only just beginning to come to terms with the dispossession and exclusion from land that Black, Indigenous, and other people of color have faced for centuries. Our desire to learn more and reflect on how we can do better is the reason we chose our conference theme this year: Building a Stronger Land Movement through Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. -

Mashantucket Pequot Tribe V. Town of Ledyard: the Preemption of State Taxes Under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2014 Mashantucket Pequot Tribe v. Town of Ledyard: The Preemption of State Taxes under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment Edward A. Lowe Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Recommended Citation Lowe, Edward A., "Mashantucket Pequot Tribe v. Town of Ledyard: The Preemption of State Taxes under Bracker, the Indian Trader Statutes, and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act Comment" (2014). Connecticut Law Review. 267. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/267 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 47 NOVEMBER 2014 NUMBER 1 Comment MASHANTUCKET PEQUOT TRIBE V. TOWN OF LEDYARD: THE PREEMPTION OF STATE TAXES UNDER BRACKER, THE INDIAN TRADER STATUTES, AND THE INDIAN GAMING REGULATORY ACT EDWARD A. LOWE The Indian Tribes of the United States occupy an often ambiguous place in our legal system, and nowhere is that ambiguity more pronounced than in the realm of state taxation. States are, for the most part, preempted from taxing the Indian Tribes, but something unique happens when the state attempts to levy a tax on non-Indian vendors employed by a Tribe for work on a reservation. The state certainly has a significant justification for imposing its tax on non-Indians, but at what point does the non-Indian vendor’s relationship with the Tribe impede the state’s right to tax? What happens when the taxed activity is a sale to the Tribe? And what does it mean when the taxed activity has connections to Indian Gaming? This Comment explores three preemption standards as they were interpreted by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in a case between the State of Connecticut and the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe. -

Hyde Park Historical Record (Vol

' ' HYDE PARK ' ' HISTORICAL RECORD ^ ^ VOLUME IV : 1904 ^ ^ ISe HYDE PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY j< * HYDE PARK, MASSACHUSETTS * * HYDE PARK HISTORICAL RECORD Volume IV— 1904 PUBLISHED BY THE HYDE PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY HYDE PARK, MASS. PRESS OF . THE HYDE PARK GAZETTE . 1904 . OFFICERS FOR J904 President Charles G. Chick Recording Secretary Fred L. Johnson Corresponding Secretary and Librarian Henry B. Carrington, 19 Summer Street, Hyde Park, Mass. Treasurer Henry B. Humphrey Editor William A. Mowry, 17 Riverside Square, Hyde Park, Mass. Curators Amos H. Brainard Frank B. Rich George L. Richardson J. Roland Corthell. George L. Stocking Alfred F. Bridgman Charles F. Jenney Henry B, Carrington {ex ofido) CONTENTS OF VOLUME IV. THEODORE DWIGHT WELD 5-32 IVi'lliam Lloyd Garrison, "J-r., Charles G. Chick, Henry B. Carrington, Mrs. Albert B. Bradley, Mrs. Cordelia A. Pay- son, Wilbur H. Po'vers, Francis W. Darling; Edtvard S. Hathazvay. JOHN ELIOT AND THE INDIAN VILLAGE AT NATICK . 33-48 Erastus Worthington. GOING WEST IN 1820. George L. Richardson .... 49-67 EDITORIAL. William A. Mowry 68 JACK FROST (Poem). William A. Mo-vry 69 A HYDE PARK MEMORIAL, 18SS (with Ode) .... 70-75 Henry B- Carrington. HENRY A. RICH 76, 77 William y. Stuart, Robert Bleakie, Henry S. Bunton. DEDICATION OF CAMP MEIGS (1903) 78-91 Henry B. Carrington, Augustus S. Lovett, BetiJ McKendry. PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY SINCE 1892 . 92-100 Fred L. 'Johnso7i. John B. Bachelder. Henry B- Carrington, Geo. M. Harding, yohn y. E7ineking ..... 94, 95 Gov. F. T. Greenhalge. C. Fred Allen, John H. ONeil . 96 Annual Meeting, 1897. Charles G. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Vol. 09 Mohegan-Pequot

Ducksunne, he falls down (dû´ksûnî´), perhaps cogn. with N. nu´kshean it falls down. Cf. Abn. pagessin it falls, said of a thunderbolt. Duckwong, mortar (dûkwâ´ng) = N. togguhwonk; RW. tácunuk; Abn. tagwaôgan; D. tachquahoakan, all from AMERICAN LANGUAGE the stem seen in N. togkau he pounds. See REPRINTS teecommewaas. Dunker tei, what ails you? (dûn kêtîâ´î). Dûn = Abn. tôni what; ke is the 2d pers.; t is the infix before a stem beginning with a vowel, and îâ´î is the verb ‘to be.’ Cf. Abn. tôni k-dâyin? ‘how are you,’ or ‘where are you?’ VOL. 9 Dupkwoh, night, dark (dû´pkwû) = Abn. tebokw. Loc. of dû´pkwû is dû´pkwûg. Een, pl. eenug, man (în, î´nûg) = N. ninnu, seen also in Abn. -winno, only in endings. Cf. Ojibwe inini. Trumbull says, in ND. 292, that N. ninnu emphasizes the 3d pers., and through it the 1st pers. Thus, noh, neen, n’un ‘he is such as this one’ or ‘as I am.’ Ninnu was used only when speaking of men of the Indian race. Missinûwog meant men of other races. See skeedumbork. Ewo, ewash, he says, say it; imv. (î´wó, î´wâs&). This con- tains the same stem as Abn. i-dam he says it. Cf. also RW. teagua nteawem what shall I say? In Peq. nê-îwó = I say, without the infixed -t. Gawgwan, see chawgwan. Ge, ger, you (ge). This is a common Algonquian heritage. 22 Chunche, must (chû´nchî) = Abn. achowi. This is not in N., where mos = must (see mus). -

The Beginning of Winchester on Massachusett Land

Posted at www.winchester.us/480/Winchester-History-Online THE BEGINNING OF WINCHESTER ON MASSACHUSETT LAND By Ellen Knight1 ENGLISH SETTLEMENT BEGINS The land on which the town of Winchester was built was once SECTIONS populated by members of the Massachusett tribe. The first Europeans to interact with the indigenous people in the New Settlement Begins England area were some traders, trappers, fishermen, and Terminology explorers. But once the English merchant companies decided to The Sachem Nanepashemet establish permanent settlements in the early 17th century, Sagamore John - English Puritans who believed the land belonged to their king Wonohaquaham and held a charter from that king empowering them to colonize The Squaw Sachem began arriving to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Local Tradition Sagamore George - For a short time, natives and colonists shared the land. The two Wenepoykin peoples were allies, perhaps uneasy and suspicious, but they Visits to Winchester were people who learned from and helped each other. There Memorials & Relics were kindnesses on both sides, but there were also animosities and acts of violence. Ultimately, since the English leaders wanted to take over the land, co- existence failed. Many sachems (the native leaders), including the chief of what became Winchester, deeded land to the Europeans and their people were forced to leave. Whether they understood the impact of their deeds or not, it is to the sachems of the Massachusetts Bay that Winchester owes its beginning as a colonized community and subsequent town. What follows is a review of written documentation KEY EVENTS IN EARLY pertinent to the cultural interaction and the land ENGLISH COLONIZATION transfers as they pertain to Winchester, with a particular focus on the native leaders, the sachems, and how they 1620 Pilgrims land at Plymouth have been remembered in local history. -

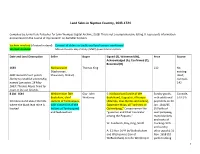

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. -

A Grammar of the Nipmuck Language

A GRAMMAR OF THE NIPMUCK LANGUAGE BY HOLLY SUZANNE GUSTAFSON ATbesis Submitted to the Faceof Graduate Studies In Partial Fulnlment of the Requirements For tbe Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Deparament of Linguistics University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba O Copyright by HoUy Gustafson 200 National Library Bibliothéque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingîm Ottawa ON KlAûN4 O(tawaON K1AW canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fih, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copy~@tin this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts f?om it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES +te*+ COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE A Grammlr of the Nipmach Languagc BY HoUy Suzanne Gartrfson A ThesiJ/Prricticarn sabmitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of &Manitobain partiai fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of HOLLY SUZANNE GUSTAFSON O 2000 Permission has ben grrnted to the Libnry of The University of Manitoba to Iend or seii copies of this thesidpncticum, to the National Librrry of Caoadi ta microfilm this thesidpracticum and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to Dissertations Abstracts International ta publish an abstract of this thesis/pmcticum. -

The Life and Times of Kateri Tekakwitha

[10][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][11][1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] [Pg vi]vii]viii]ix]xiv]2]3]4]5]6]7]8]9]10]11]12]13]14]15]16]17]18]19]20]21]22]23]24]25]26]27]28]29]30]31]32]33]34]35]36]37]38]39]40]41]42]43]44]45]46]47]48]49]50]51]52]53]54]55]56]57]58]59]60]61]62]63]64]65]66]67]68]69]70]71]72]73]74]75]76]77]78]79]80]81]82]83]84]85]86]87]88]89]90]91]92]93]94]95]96]97]98]99]100]101]102]103]104]105]106]107]108]109]110]111]112]113]114]115]116]117]118]119]120]121]122]123]124]125]126]127]128]129]130]131]132]133]134]135]136]137]138]139]140]141]142]143]144]145]146]147]148]149]150]151]152]153]154]155]156]157]158]159]160]161]162]163]164]165]166]167]168]169]170]171]172]173]174]175]176]177]178]179]180]181]182]184]185]186]187]188]189]190]191]192]193]194]195]196]197]198]199]200]201]202]203]204]205]206]207]208]209]210]211]212]213]214]215]216]217]218]219]220]221]222]223]224]225]226]227]228]229]230]231]232]233]234]235]236]237]238]239]240]241]242]243]244]245]246]247]248]249]250]251]252]253]254]255]256]257]258]259]260]261]262]263]264]265]266]267]268]269]270]271]272]273]274]275]276]277]278]279]280]281]282]283]284]285]286]287]288]289]290]291]292]293]294]295]296]297]298]299]302]303]304]305]306]307]308]309]310]311]312]313]314] THE LIFE AND TIMES [Pg 183] OF KATERI TEKAKWITHA, 1656-1680. -

NATIVE AMERICANS in MASSACHUSETTS: NEW HOMECOMINGS and ONGOING DISPLACEMENTS by J

NATIVE AMERICANS IN MASSACHUSETTS: NEW HOMECOMINGS AND ONGOING DISPLACEMENTS By J. Cedric Woods, Director, Institute for New England Native American Studies, UMass Boston hat is now the Commonwealth of For these people, catastrophic population loss followed Massachusetts, was, is and always will sustained contact with Europeans due to disease, Wbe Indian Country. The names used enslavement and warfare, but nevertheless Native for the inhabitants and settlements of this land have Peoples are still very much present in Massachusetts. changed over the last 10,000 years, but thousands of The trends of loss and survival would continue, Indigenous Peoples from the Massachusett, Nipmuc although punctuated by periods of stabilization, and Wampanoag tribes historically resided in the areas throughout much of the 17th century. The 18th century on which this section focuses: the town of Aquinnah brought new challenges as the ongoing entanglement on Martha’s Vineyard (what Natives call Noepe) and of Natives in European, and later American, military the Greater Boston region (Figure 4.1). conflicts and physically dangerous employment (like FIGURE 4.1 Several distinct Native Peoples inhabited what is now Massachusetts and points south. Tribal territories of Southern New England. Around 1600. Author: Nikater, adapted to English by Hydrargyrum. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tribal_Territories_Southern_New_England.png#/media/File:Tribal_Territories_ Southern_New_England.png 41 NATIVE AMERICANS IN MASSACHUSETTS whaling) led to chronically disproportionate loss For those unfamiliar with ongoing trends in Indian of life, particularly of Native men (Figure 4.2). The Country demographics, a look at the most commonly 19th century saw efforts by the Commonwealth to used Census data for the Massachusetts Native politically dismantle Native communities (whether population may be deceiving. -

The Easton Family of Southeast Massachusetts: the Dynamics Surrounding Five Generations of Human Rights Activism 1753--1935

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935 George R. Price The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Price, George R., "The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9598. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: Date: 7 — 2 ~ (p ~ O b Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.