Sharia in the City Negotiation and Construction of Moral Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print This Article

Journal of tourism – studies and research in tourism [Issue 29] DEVELOPMENT PROSPECT OF TOURISM INDUSTRY IN MURSHIDABAD – JIAGANJ CD BLOCK, MURSHIDABAD DISTRICT, WESTBENGAL Subham KUMAR ROY Faculty, Dept. of Geography, Prof. Syed Nurul Hasan College,Farakka, Murshidabad [email protected] Chumki MONDAL Khandra College, Paschim Barddhaman. Abstract: Temporary movement of people from their place of birth or workplace to place of destination what they want to visit. Tourism is a growing industry it can help to employment generation and help to strength economy of country. Human environment interaction and quality of the environment is primary key to attract the tourist. This can lead to considerable pressure on the environment and in that process can accelerate the rate of environmental degradation. The main objectives of this paper are to identify the tourist spots surrounding study area, to draw the perception of tourist about the infrastructure and regarding problems and provide some probable recommendation for sustainable tourism development. To prepare this paper simple field based methodology are applied. Geo-informatics has been used for collecting data and prepare necessary map making. Various books, journals, report, were used for preparing secondary data source. Tourism should be undertaken with equity in mind, not to do unfair activities which make access or pollution free environment and appropriate economic use of natural and human environment. Through this paper we will provide some recommendations which are associated with eco friendly, sustainability and dynamic in nature. Keywords: Tourism, Environmental degradation, Sustainability, Dynamic, Eco friendly. JEL Classification: L83 I. INTRODUCTION: potential of tourism and last of all impact of tourism in the economy of Most of the philosopher visited several places Murshidabad district. -

Slowly Down the Ganges March 6 – 19, 2018

Slowly Down the Ganges March 6 – 19, 2018 OVERVIEW The name Ganges conjures notions of India’s exoticism and mystery. Considered a living goddess in the Hindu religion, the Ganges is also the daily lifeblood that provides food, water, and transportation to millions who live along its banks. While small boats have plied the Ganges for millennia, new technologies and improvements to the river’s navigation mean it is now also possible to travel the length of this extraordinary river in considerable comfort. We have exclusively chartered the RV Bengal Ganga for this very special voyage. Based on a traditional 19th century British design, our ship blends beautifully with the timeless landscape. Over eight leisurely days and 650 kilometres, we will experience the vibrant, complex tapestry of diverse architectural expressions, historical narratives, religious beliefs, and fascinating cultural traditions that thrive along the banks of the Ganges. Daily presentations by our expert study leaders will add to our understanding of the soul of Indian civilization. We begin our journey in colourful Varanasi for a first look at the Ganges at one of its holiest places. And then by ship we explore the ancient Bengali temples, splendid garden-tombs, and vestiges of India’s rich colonial past and experience the enduring rituals of daily life along ‘Mother Ganga’. Our river journey concludes in Kolkatta (formerly Calcutta) to view the poignant reminders of past glories of the Raj. Conclude your trip with an immersion into the lush tropical landscapes of Tamil Nadu to visit grand temples, testaments to the great cultural opulence left behind by vanished ancient dynasties and take in the French colonial vibe of Pondicherry. -

Annual Report 2007-2008

MARKING A DECADE OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Annual Report 2007-2008 Contents Secretary General’s Address to the Annual General Meeting 4 Advocating Muslim Concerns 12 Committee Reports Business and Economics 13 Chaplaincy 14 Education 16 Europe and International Affairs 17 Food Standards 18 Health and Medical 19 Interfaith Relations 19 Legal Affairs 21 London Affairs 21 Media 22 Membership 23 Mosque and Community Affairs 24 Public Affairs 25 Research and Documentation 26 Social and Family Affairs 28 Youth and Sports 28 Project Reports Muslim Spiritual Care Provision in the NHS 28 Capacity Building of Mosques and Islamic Organisations (M100) 29 Books for Schools 30 Footsteps 31 Appendices (A) OBs, BoCs, Advisors, CWC and other Committees’ members 33 (B) Press Releases 37 (C) Consultations and Reports 38 (D) MCB affiliates 38 4 In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful Secretary General’s Address to the Annual General Meeting of the General Assembly Respected Chair, distinguished guests, brothers and sisters - Assalamu Alaikum wa Rahmatullah We are meeting in very challenging times for the Muslim communities in Britain, as well as across the rest of the world. In the UK, the media’s persistent focus on finding anything and everything problematic with Islam or Muslims has, to some extent, entered the subconscious of many parts of British society. Sober thinking parts of the academia and intelligentsia are now getting quite perturbed about it. This makes the on-going work of the MCB even more critical and relevant in today's climate and in the latter part of this address I will say a few words about this. -

No. of Questions: 40 Correct: ______Full Mark: 40 Wrong: ______

WEEKLY CURRENTAFFAIRS QUESTION DISCUSSION – 22.04.2019 TO 27.04.2019 No. of Questions: 40 Correct: ____________ Full Mark: 40 Wrong: _____________ Time: 20 min Mark Secured: _______ 1. Which country topped the Index of Cancer Preparedness for 2019 released by Economist Intelligence Unit? A) Romania B) Netherlands C) Germany D) Australia 2. Which entity has collaborated with India Post for digitizing 1.5 lakh post offices in India? A) TCS B) Microsoft C) IBM D) Intel 3. Which country has recently set up Coordinating Council for attracting foreign investments, mainly from India? A) Turkmenistan B) Uzbekistan C) Kyrgyzstan D) Kazakhstan 4. Which International organisation has issued recommendations on the usage of screen for kids under 5 years of age? A) United Nations B) UNESCO C) WHO D) UNICEF 5. Indian Army and National Hydroelectric Power Corporation Limited, has signed MoU to build four underground tunnels along the borders of which country? i. Bangladesh ii. China iii. Pakistan iv. Afghanistan A) Option i & ii B) Option ii & iv C) Option iii & ii D) Option iv & i 6. Where was the Asian Boxing Championship 2019 held? A) Beijing B) Bangkok C) Jakarta D) New Delhi 7. Who won the Corporate Excellence award in the Manufacturing Industry, from Enterprise Asia of Malaysia for 2019? A) Andreas Dulger B) Thomas Koetzing C) Prasanna Kumar Rao D) Rainer Dulger 8. What is the name of the world’s first floating nuclear power plant that is tested by Rosenergoatom of Russia? A) Bashkir B) Balakovo C) Akademik Lomonosov D) Beloyarsk 9. When was the first official International Day of Multilateralism and Diplomacy for Peace observed? A) 21st April B) 22nd April C) 24th April D) 23rd April 10. -

List of Newly Enrolled Hgos

Sr # Enr # Company Chief CNIC No. Address Phone/Cell # SECP Paidup NMD Authoriz Establis Experie Not Not FBR Audit Total Executive/Directors Reg Capital Cert. ed hed nce Convict black Certific Reports Marks Capital Office ed Listed ate 1 11000 Shandur Travel & Tours (Pvt) Ltd Naqeeb Ahmed 17301-9912747-9 4-A, Mandni Market Shoba 091-2562213-14 Chowk,Khyber Bazar,Peshawar. 8 10 3 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 26 Shamila Naqoob 34104-2236293-5 2 11001 Al Afghan Travels Pvt Ltd Khalid Sattar 12101-4300214-1 Office No. 10, Municipal Shopping 0966-715896 Center,East Circular Road, Dera Ismail Khan 8 10 3 5 2 0 0 5 0 15 48 Sharif Ullah 12101-0983211-9 Muhammad 12103-9656856-7 Mushtaq 3 11002 Nabawi Hajj & Umrah Services (Pvt) Muhammad Rashid 16102-3802681-9 Office B-11, Haji Nek Amal Khan 0937-552324 Limited. Khan Market, Takkar Road, Tehsil Takht 0333-9332469 Bhai 16 10 3 5 3 0 0 0 0 0 37 Touseef-un-Nihar 17301-0649296-6 Haji Muhammad 16102-5748133-9 Anwar Parwana 4 11003 Karwan-E-Buner Hajj & Umrah Tufail Akbar 16101-3524162-1 Near PSO Petrol Pump, Swabi Road 0937-561433 Services (Pvt) Ldt. Par Hoto Mardan 14 10 3 5 0 0 0 5 0 0 37 Syed Shahid Ali Shah 16101-0764643-9 5 11004 Tatara Hajj & Umrah Services (Pvt) Qasim Gull 21202-6421920-3 Office No. 2 & 3, Block-B, 2nd Floor, 091-5816636 Ltd Awami Market Karkhana, Peshawar 16 10 3 0 0 0 0 5 3 0 37 Bahi Khan 21202-4092515-7 Saida Gul Khan 21202-1614495-5 6 11005 Samawat Hajj And Umrah Services Pir Muhammad 11201-0378178-7 SHO,PNO 10- Shaikh Market, Near 0969-510816 Pvt Ltd Anwar City Police Station, Lukki Marwat 0300-8763109 14 10 3 5 0 0 0 0 0 15 47 H. -

Alternative Dispute Resolution in Islam: an Analysis

Summer Issue 2017 ILI Law Review Vol. I ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION IN ISLAM: AN ANALYSIS Dr. Vandana Singh* “O you who believe! Stand out firmly for Allah as witnesses to fair dealings and let not the hatred of others to you make you swerve to wrong and depart from justice. Be just, that is next to piety. Fear Allah, indeed Allah is well acquainted with all that you do.” Quran: Chapter 5 Verse 8 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to look at methods of dispute resolution in Islam which is nearly two thousand years old. It is commonly believed that the Alternative Dispute Resolution has emerged and originated from the west from past few decades. On the contrary, it is claimed by many Islamic Jurist that the ADR processes like Negotiation, Mediation, Med-Arb, and Arbitration are practiced in Islam from 1400 years and are mentioned in holy Quran. The present paper is an attempt to analyze practice and concept of Alternative Dispute Resolution from an Islamic theological perspective. In light of the clear foundation for these guiding principles to govern Islamic dispute resolution, this chapter will outline the foundations for Alternative Dispute Resolution in Islam and assess the theory and practice of sullh and taken in contemporary times. I Introduction ……………………………….................... 137-138 II Historical Background of ADR in Islam ...................... 138-142 III Process of ADR in Islam ……………………………… 142-146 I Introduction AS THE world is getting smaller due to continuous exchange of information and knowledge and boundaries between cultures, religion and civilisationsare gradually gettingcollapsed, the study of cross-cultural and multi-religious practice is of profound need. -

Short Communications Caring for Muslim Patients

Short Communications Caring for Muslim Patients - Some Religious Issues Iftikhar AKa and Parvez IPa aDepartment of Human Nutrition, NWFP Agriculture University Peshawar, Pakistan ABSTRACT Islam is a universal religion and a comprehensive way of life that cannot be separated from patients. Muslim patients are not just passive recipients of medical decisions, but have their own religious views and beliefs about how they would like to be cared for by the medical profession. With the increasing Muslim population in the west, problems arise when a Muslim patient is admitted to a hospital with non-Muslim health care- giver, particularly related to dietary and nutritional issues. The health team should be aware of the religious prohibitions in Islam such as wine or alcohol, flesh of swine, reptiles, birds with talons, canine animals or scavenging creatures, intoxicants etc. The guidelines presented in this paper would enable the health provider to serve their Muslim patients in the most appropriate manner. KEYWORDS: Muslim patients, Hospital diet, Forbidden foods INTRODUCTION Eating, like any other act of the Muslims, is a matter of water should be made available to them whenever of worship if done Islamically. Muslims begin and end they use a bed pan and at meal times. It is preferable eating with the name of Allah. Islam reminds Muslims that female patients are cared for by females and male of foods and drinks as a provision of Allah provided patients by males, particularly during confinement. to them for survival and for maintaining good health. The modesty of a woman must be respected and the Muslims will eat only those foods, which are allowed husband may wish to be present during childbirth. -

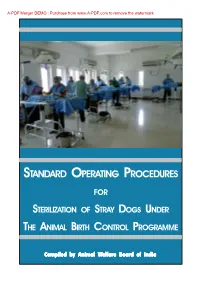

Standard Operating Procedures

A-PDF Merger DEMO : Purchase from www.A-PDF.com to remove the watermark STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES FOR STERILIZATION OF STRAY DOGS UNDER THE ANIMAL BIRTH CONTROL PROGRAMME Compiled by Animal Welfare Board of India Animal Birth Control (ABC) & Anti-Rabies Programme is being implemented in almost all major metros of India Over 1 lakh stray dogs are sterilized & vaccinated against rabies every year under the Animal Birth Control (2001) Dog Rules The Animal Birth Control Programme is currently being implemented in over 60 cities all over India, including major metros like Delhi, Jaipur, Chennai, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Jodhpur and Kalimpoong. In Tamil Nadu & Goa, since 2007, the Animal Birth Control and Anti-Rabies Vaccination Programme has been successfully implemented for the entire state. This has led to Tamil Nadu state pioneering a new concept of a Participatory Model of the ABC Programme in 50 Municipalities and 5 Municipal Corporations, with 50% cost sharing by local bodies on participatory basis. Similarly, the Union Territory of Delhi too has adopted the Participatory Model of the ABC Programme since 2008. Tamil Nadu has also been at the forefront of rabies control initiatives, having constituted the country’s first State level Coordination Committee on Rabies Control and Prevention in January, 2009, with the first meeting held on April 20th, 2009. The Animal Welfare Board of India is promoting such initiatives throughout the country. In all Metros, where the ABC Programme has been successfully implemented in India, a significant reduction in the number of human rabies cases has been noted. The Animal Birth Control Programme is the only scientifically proven method to reduce the stray dog population in a city or town. -

General Awareness–Current Affairs Month of March-2019

GENERAL AWARENESS–CURRENT AFFAIRS MONTH OF MARCH-2019 List of Important Days March 1 - Zero Discrimination Day (Theme – “Act to change laws that Discriminate”) March 4 - National Safety Day (Themes – “Cultivate and Sustain A Safety Culture for Building Nation”) Mar 4-10 - National Safety Week March 7 - Janaushadhi Diwas March 8 - International Women’s Day (Theme – “Think Equal, Build Smart, Innovate for Change”). March 12 - World Day against Cyber Censorship March 12 - 30th anniversary of the World Wide Web (WWW) March 14 - (2nd Thursday of March) World Kidney Day (Theme - “Kidney Health for Everyone Everywhere”) March 14 - Pi Day (Pi's value (3.14)) March 15 - World Consumer Rights Day (In India this day is celebrated as Viswa Upabhokta Adhikar Diwas). (Theme – “Trusted Smart Products”) March 20 - International Day of Happiness. (Theme – “Happier Together”) March 20 - World Day of Theatre for Children and Young People March 20 - World Sparrow Day. (Theme – “I LOVE Sparrows”) March 21 - International Day of Forests. (Theme “Forests and Education”) March 21 - World Poetry Day March 21 - World Down Syndrome Day March 21 - International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (Theme – “Mitigating and countering rising nationalist populism and extreme supremacist ideologies”) March 21 - World Puppetry Day March 22 - World Water Day (Theme – “Leaving no one behind”) March 23 - World Meteorological Day (Theme – “The Sun, the Earth and the Weather”) March 23 - 88th Shaheed Diwas (Martyr’s Day) March 24 - World Tuberculosis (TB) Day (Theme – “It’s time”) March 25 - International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and Transatlantic Slave Trade. (Theme – “Remember Slavery: The Power of the Arts for Justice”) March 26 - Independence Day of Bangladesh March 27 - World Theatre Day (WTD) March 30 - Rajasthan Diwas Reserve Bank of India • The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has fined Yes Bank ₹1 crore for not complying with its directions about SWIFT, a financial messaging software. -

Legend Magazine (June

LEGEND MAGAZINE (JUNE - 2019) June Current Affairs and Quiz, English, Banking Awareness, Simplification Exclusively prepared for RACE students Issue: 19 | Page : 48 | Topic : Legend of June | Price: Not for Sale JUNE MONTH CA • The Indian government has Govt. Plans To Raise USD 84 Billion From demanded Whatsapp, the Facebook-owned Airwaves Auction In 2019: NATIONAL messaging application, to digitally fingerprint Govt. Set To Roll Out IMEI Database To Help • Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led NDA messages that are sent on its platform without People Track Stolen Mobile Phones: Government hopes to increase around $83.8 breaking the encryption. billion (Rs 5.83 trillion rupees) from its latest • The Telecom Ministry is set to roll out • AudienceNet, an UK-based social and round of airwaves auction in 2019. a Central Equipment Identity consumer research agency, reported that the Register (CEIR), a database of International • The Central government is planning to majority of the respondents in India selected Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) to help sell 8,600 megahertz of telecom airwaves WhatsApp as the preferred choice of social media people track their stolen mobile phones. across multiple frequency bands. Rs 65,789 crore network and a messaging platform. was raised in the airwaves auction held by the • People can inform the Department of Telecom • It also highlighted that about 78% of the government in 2016-17. (DoT) on losing their phones, which will, in turn, respondents trust WhatsApp to keep their blacklist their IMEI numbers. DoT had declared its • Recently, Telecom Minister Ravi Shankar personal details private and secure. plan to implement this project in July 2017 and a Prasad announced the debut auction of fifth- pilot was conducted in Maharashtra. -

Indian Embassies/Consulates in Gulf

INDIAN EMBASSIES/CONSULATES IN GULF EMBASSY OF INDIA – BAHRAIN EMBASSY OF INDIA – JORDAN BUILDING 182, ROAD 2608 POST BOX 2168, 1ST CIRCLE AREA 326, GHUDAIBIYA AMMAN 11181, JORDAN P.O.BOX NO. 26106, ADLIYA, BAHRAIN TEL: 00-962-6-4622098/4637262 TEL: 00-973-17712683/17712785/17712649 FAX: 00-962-6-4659540 FAX: 00-973-17715527 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] SHRI. H.C.S. DHODY – AMBASSADOR Internet: www.indianembassy-bah.com SHRI. KRISHAN KUMAR – COUNSELLOR MR. BALKRISHNA SHETTY - AMBASSADOR MR. H. R. MOHEY – COUNSELLOR MR. O.P.WADHWA - FIRST SECRETARY (COM) EMBASSY OF INDIA – EGYPT EMBASSY OF INDIA – KUWAIT 5, AZIZ ABAZA STREET, ZAMALEK DIPLOMATIC ENCLAVE P.O.BOX NO. 718, CAIRO 11511 ARABIAN GULF STREET EGYPT P.O.BOX NO. 1450, SAFAT 13015, KUWAIT TEL: 00-20-2-7360052/7363051/7356053 TEL: 00-965-2530600/612/614/2510891/2530600 FAX: 00-20-2-7364038 FAX: 00-965-2525811/2571192/2573910 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected]/ [email protected] SHRI. SHIV SHANKAR MUKHERJEE AMBASSADOR SHRI. PRABHU DAYAL – AMBASSADOR SHRI. ASHOK WARRIER – ATTACHE COMM. MR. SATISH SAKLESHPUR, ATTACHE (COMMERCIAL) SHRI. K.J.S.SODHI – COUNSELLOR (E & P) EMBASSY OF INDIA – IRAN EMBASSY OF INDIA – OMAN 46, MIR-EMAD, CORNER OF 9TH STREET P.O.BOX 1727, RUWI 112 DR. BEHESHTI AVENUE MUSCAT, SULTANATE OF OMAN P.O.BOX 15875-4118, TEHRAN, TEL: 00-968-7714120/7714274/7714239 ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN FAX: 00-968-7717503/7716209 TEL: 0098-21-8753474/8782992 (O) E-mail: [email protected] FAX: 0098-21-8745557 SHRI. -

Saudi Publications on Hate Ideology Invade American Mosques

SAUDI PUBLICATIONS ON HATE IDEOLOGY INVADE AMERICAN MOSQUES _______________________________________________________________________ Center for Religious Freedom Freedom House 2 Copyright © 2005 by Freedom House Published by the Center for Religious Freedom Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of Freedom House, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Center for Religious Freedom Freedom House 1319 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20036 Phone: 202-296-5101 Fax: 202-296-5078 Website: www.freedomhouse.org/religion ABOUT THE CENTER FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM The CENTER FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM is a division of Freedom House. Founded more than sixty years ago by Eleanor Roosevelt, Wendell Willkie, and other Americans concerned with the mounting threats to peace and democracy, Freedom House has been a vigorous proponent of democratic values and a steadfast opponent of dictatorship of the far left and the far right. Its Center for Religious Freedom defends against religious persecution of all groups throughout the world. It insists that U.S foreign policy defend those persecuted for their religion or beliefs around the world, and advocates the right to religious freedom for every individual. Since its inception in 1986, the Center, under the leadership of human rights lawyer Nina Shea, has reported on the religious persecution of individuals and groups abroad and undertaken advocacy on their behalf in the media, Congress, State Department, and the White House. It also sponsors investigative field missions. Freedom House is a 501(c)3 organization, headquartered in New York City.