Julia Language Documentation Release 0.4.6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bit Shifts Bit Operations, Logical Shifts, Arithmetic Shifts, Rotate Shifts

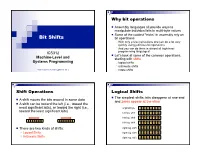

Why bit operations Assembly languages all provide ways to manipulate individual bits in multi-byte values Some of the coolest “tricks” in assembly rely on Bit Shifts bit operations With only a few instructions one can do a lot very quickly using judicious bit operations And you can do them in almost all high-level ICS312 programming languages! Let’s look at some of the common operations, Machine-Level and starting with shifts Systems Programming logical shifts arithmetic shifts Henri Casanova ([email protected]) rotate shifts Shift Operations Logical Shifts The simplest shifts: bits disappear at one end A shift moves the bits around in some data and zeros appear at the other A shift can be toward the left (i.e., toward the most significant bits), or toward the right (i.e., original byte 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 toward the least significant bits) left log. shift 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 left log. shift 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 left log. shift 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 There are two kinds of shifts: right log. shift 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 Logical Shifts right log. shift 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 Arithmetic Shifts right log. shift 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 Logical Shift Instructions Shifts and Numbers Two instructions: shl and shr The common use for shifts: quickly multiply and divide by powers of 2 One specifies by how many bits the data is shifted In decimal, for instance: multiplying 0013 by 10 amounts to doing one left shift to obtain 0130 Either by just passing a constant to the instruction multiplying by 100=102 amounts to doing two left shifts to obtain 1300 Or by using whatever -

UNIX and Computer Science Spreading UNIX Around the World: by Ronda Hauben an Interview with John Lions

Winter/Spring 1994 Celebrating 25 Years of UNIX Volume 6 No 1 "I believe all significant software movements start at the grassroots level. UNIX, after all, was not developed by the President of AT&T." Kouichi Kishida, UNIX Review, Feb., 1987 UNIX and Computer Science Spreading UNIX Around the World: by Ronda Hauben An Interview with John Lions [Editor's Note: This year, 1994, is the 25th anniversary of the [Editor's Note: Looking through some magazines in a local invention of UNIX in 1969 at Bell Labs. The following is university library, I came upon back issues of UNIX Review from a "Work In Progress" introduced at the USENIX from the mid 1980's. In these issues were articles by or inter- Summer 1993 Conference in Cincinnati, Ohio. This article is views with several of the pioneers who developed UNIX. As intended as a contribution to a discussion about the sig- part of my research for a paper about the history and devel- nificance of the UNIX breakthrough and the lessons to be opment of the early days of UNIX, I felt it would be helpful learned from it for making the next step forward.] to be able to ask some of these pioneers additional questions The Multics collaboration (1964-1968) had been created to based on the events and developments described in the UNIX "show that general-purpose, multiuser, timesharing systems Review Interviews. were viable." Based on the results of research gained at MIT Following is an interview conducted via E-mail with John using the MIT Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS), Lions, who wrote A Commentary on the UNIX Operating AT&T and GE agreed to work with MIT to build a "new System describing Version 6 UNIX to accompany the "UNIX hardware, a new operating system, a new file system, and a Operating System Source Code Level 6" for the students in new user interface." Though the project proceeded slowly his operating systems class at the University of New South and it took years to develop Multics, Doug Comer, a Profes- Wales in Australia. -

ML Module Mania: a Type-Safe, Separately Compiled, Extensible Interpreter

ML Module Mania: A Type-Safe, Separately Compiled, Extensible Interpreter The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ramsey, Norman. 2005. ML Module Mania: A Type-Safe, Separately Compiled, Extensible Interpreter. Harvard Computer Science Group Technical Report TR-11-05. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:25104737 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ¡¢ £¥¤§¦©¨ © ¥ ! " $# %& !'( *)+ %¨,.-/£102©¨ 3¤4#576¥)+ %&8+9©¨ :1)+ 3';&'( )< %' =?>A@CBEDAFHG7DABJILKM GPORQQSOUT3V N W >BYXZ*[CK\@7]_^\`aKbF!^\K/c@C>ZdX eDf@hgiDf@kjmlnF!`ogpKb@CIh`q[UM W DABsr!@k`ajdtKAu!vwDAIhIkDi^Rx_Z!ILK[h[SI ML Module Mania: A Type-Safe, Separately Compiled, Extensible Interpreter Norman Ramsey Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences Harvard University Abstract An application that uses an embedded interpreter is writ- ten in two languages: Most code is written in the original, The new embedded interpreter Lua-ML combines extensi- host language (e.g., C, C++, or ML), but key parts can be bility and separate compilation without compromising type written in the embedded language. This organization has safety. The interpreter’s types are extended by applying a several benefits: sum constructor to built-in types and to extensions, then • Complex command-line arguments aren’t needed; the tying a recursive knot using a two-level type; the sum con- embedded language can be used on the command line. -

Tierless Web Programming in ML Gabriel Radanne

Tierless Web programming in ML Gabriel Radanne To cite this version: Gabriel Radanne. Tierless Web programming in ML. Programming Languages [cs.PL]. Université Paris Diderot (Paris 7), 2017. English. tel-01788885 HAL Id: tel-01788885 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01788885 Submitted on 9 May 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Thèse de doctorat de l’Université Sorbonne Paris Cité Préparée à l’Université Paris Diderot au Laboratoire IRIF Ecole Doctorale 386 — Science Mathématiques De Paris Centre Tierless Web programming in ML par Gabriel Radanne Thèse de Doctorat d’informatique Dirigée par Roberto Di Cosmo et Jérôme Vouillon Thèse soutenue publiquement le 14 Novembre 2017 devant le jury constitué de Manuel Serrano Président du Jury Roberto Di Cosmo Directeur de thèse Jérôme Vouillon Co-Directeur de thèse Koen Claessen Rapporteur Jacques Garrigue Rapporteur Coen De Roover Examinateur Xavier Leroy Examinateur Jeremy Yallop Examinateur This work is licensed under a Creative Commons “Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International” license. Abstract Eliom is a dialect of OCaml for Web programming in which server and client pieces of code can be mixed in the same file using syntactic annotations. -

Stan: a Probabilistic Programming Language

JSS Journal of Statistical Software MMMMMM YYYY, Volume VV, Issue II. http://www.jstatsoft.org/ Stan: A Probabilistic Programming Language Bob Carpenter Andrew Gelman Matt Hoffman Columbia University Columbia University Adobe Research Daniel Lee Ben Goodrich Michael Betancourt Columbia University Columbia University University of Warwick Marcus A. Brubaker Jiqiang Guo Peter Li University of Toronto, NPD Group Columbia University Scarborough Allen Riddell Dartmouth College Abstract Stan is a probabilistic programming language for specifying statistical models. A Stan program imperatively defines a log probability function over parameters conditioned on specified data and constants. As of version 2.2.0, Stan provides full Bayesian inference for continuous-variable models through Markov chain Monte Carlo methods such as the No-U-Turn sampler, an adaptive form of Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling. Penalized maximum likelihood estimates are calculated using optimization methods such as the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno algorithm. Stan is also a platform for computing log densities and their gradients and Hessians, which can be used in alternative algorithms such as variational Bayes, expectation propa- gation, and marginal inference using approximate integration. To this end, Stan is set up so that the densities, gradients, and Hessians, along with intermediate quantities of the algorithm such as acceptance probabilities, are easily accessible. Stan can be called from the command line, through R using the RStan package, or through Python using the PyStan package. All three interfaces support sampling and optimization-based inference. RStan and PyStan also provide access to log probabilities, gradients, Hessians, and data I/O. Keywords: probabilistic program, Bayesian inference, algorithmic differentiation, Stan. -

To Type Or Not to Type: Quantifying Detectable Bugs in Javascript

To Type or Not to Type: Quantifying Detectable Bugs in JavaScript Zheng Gao Christian Bird Earl T. Barr University College London Microsoft Research University College London London, UK Redmond, USA London, UK [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—JavaScript is growing explosively and is now used in to invest in static type systems for JavaScript: first Google large mature projects even outside the web domain. JavaScript is released Closure1, then Microsoft published TypeScript2, and also a dynamically typed language for which static type systems, most recently Facebook announced Flow3. What impact do notably Facebook’s Flow and Microsoft’s TypeScript, have been written. What benefits do these static type systems provide? these static type systems have on code quality? More concretely, Leveraging JavaScript project histories, we select a fixed bug how many bugs could they have reported to developers? and check out the code just prior to the fix. We manually add The fact that long-running JavaScript projects have extensive type annotations to the buggy code and test whether Flow and version histories, coupled with the existence of static type TypeScript report an error on the buggy code, thereby possibly systems that support gradual typing and can be applied to prompting a developer to fix the bug before its public release. We then report the proportion of bugs on which these type systems JavaScript programs with few modifications, enables us to reported an error. under-approximately quantify the beneficial impact of static Evaluating static type systems against public bugs, which type systems on code quality. -

Introduction Rats Version 9.0

RATS VERSION 9.0 INTRODUCTION RATS VERSION 9.0 INTRODUCTION Estima 1560 Sherman Ave., Suite 510 Evanston, IL 60201 Orders, Sales Inquiries 800–822–8038 Web: www.estima.com General Information 847–864–8772 Sales: [email protected] Technical Support 847–864–1910 Technical Support: [email protected] Fax: 847–864–6221 © 2014 by Estima. All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means with- out the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Estima 1560 Sherman Ave., Suite 510 Evanston, IL 60201 Published in the United States of America Preface Welcome to Version 9 of rats. We went to a three-book manual set with Version 8 (this Introduction, the User’s Guide and the Reference Manual; and we’ve continued that into Version 9. However, we’ve made some changes in emphasis to reflect the fact that most of our users now use electronic versions of the manuals. And, with well over a thousand example programs, the most common way for people to use rats is to pick an existing program and modify it. With each new major version, we need to decide what’s new and needs to be ex- plained, what’s important and needs greater emphasis, and what’s no longer topical and can be moved out of the main documentation. For Version 9, the chapters in the User’s Guide that received the most attention were “arch/garch and related mod- els” (Chapter 9), “Threshold, Breaks and Switching” (Chapter 11), and “Cross Section and Panel Data” (Chapter 12). -

The Evolution of Econometric Software Design: a Developer's View

Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 29 (2004) 205–259 205 IOS Press The evolution of econometric software design: A developer’s view Houston H. Stokes Department of Economics, College of Business Administration, University of Illinois at Chicago, 601 South Morgan Street, Room 2103, Chicago, IL 60607-7121, USA E-mail: [email protected] In the last 30 years, changes in operating systems, computer hardware, compiler technology and the needs of research in applied econometrics have all influenced econometric software development and the environment of statistical computing. The evolution of various representative software systems, including B34S developed by the author, are used to illustrate differences in software design and the interrelation of a number of factors that influenced these choices. A list of desired econometric software features, software design goals and econometric programming language characteristics are suggested. It is stressed that there is no one “ideal” software system that will work effectively in all situations. System integration of statistical software provides a means by which capability can be leveraged. 1. Introduction 1.1. Overview The development of modern econometric software has been influenced by the changing needs of applied econometric research, the expanding capability of com- puter hardware (CPU speed, disk storage and memory), changes in the design and capability of compilers, and the availability of high-quality subroutine libraries. Soft- ware design in turn has itself impacted applied econometric research, which has seen its horizons expand rapidly in the last 30 years as new techniques of analysis became computationally possible. How some of these interrelationships have evolved over time is illustrated by a discussion of the evolution of the design and capability of the B34S Software system [55] which is contrasted to a selection of other software systems. -

Scribble As Preprocessor

Scribble as Preprocessor Version 8.2.0.8 Matthew Flatt and Eli Barzilay September 25, 2021 The scribble/text and scribble/html languages act as “preprocessor” languages for generating text or HTML. These preprocessor languages use the same @ syntax as the main Scribble tool (see Scribble: The Racket Documentation Tool), but instead of working in terms of a document abstraction that can be rendered to text and HTML (and other formats), the preprocessor languages work in a way that is more specific to the target formats. 1 Contents 1 Text Generation 3 1.1 Writing Text Files . .3 1.2 Defining Functions and More . .7 1.3 Using Printouts . .9 1.4 Indentation in Preprocessed output . 11 1.5 Using External Files . 16 1.6 Text Generation Functions . 19 2 HTML Generation 23 2.1 Generating HTML Strings . 23 2.1.1 Other HTML elements . 30 2.2 Generating XML Strings . 32 2.3 HTML Resources . 36 Index 39 Index 39 2 1 Text Generation #lang scribble/text package: scribble-text-lib The scribble/text language provides everything from racket/base, racket/promise, racket/list, and racket/string, but with additions and a changed treatment of the module top level to make it suitable as for text generation or a preprocessor language: • The language uses read-syntax-inside to read the body of the module, similar to §6.7 “Document Reader”. This means that by default, all text is read in as Racket strings; and @-forms can be used to use Racket functions and expression escapes. • Values of expressions are printed with a custom output function. -

C Constants and Literals Integer Literals Floating-Point Literals

C Constants and Literals The constants refer to fixed values that the program may not alter during its execution. These fixed values are also called literals. Constants can be of any of the basic data types like an integer constant, a floating constant, a character constant, or a string literal. There are also enumeration constants as well. The constants are treated just like regular variables except that their values cannot be modified after their definition. Integer literals An integer literal can be a decimal, octal, or hexadecimal constant. A prefix specifies the base or radix: 0x or 0X for hexadecimal, 0 for octal, and nothing for decimal. An integer literal can also have a suffix that is a combination of U and L, for unsigned and long, respectively. The suffix can be uppercase or lowercase and can be in any order. Here are some examples of integer literals: Floating-point literals A floating-point literal has an integer part, a decimal point, a fractional part, and an exponent part. You can represent floating point literals either in decimal form or exponential form. While representing using decimal form, you must include the decimal point, the exponent, or both and while representing using exponential form, you must include the integer part, the fractional part, or both. The signed exponent is introduced by e or E. Here are some examples of floating-point literals: 1 | P a g e Character constants Character literals are enclosed in single quotes, e.g., 'x' and can be stored in a simple variable of char type. A character literal can be a plain character (e.g., 'x'), an escape sequence (e.g., '\t'), or a universal character (e.g., '\u02C0'). -

Section “Common Predefined Macros” in the C Preprocessor

The C Preprocessor For gcc version 12.0.0 (pre-release) (GCC) Richard M. Stallman, Zachary Weinberg Copyright c 1987-2021 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". This manual contains no Invariant Sections. The Front-Cover Texts are (a) (see below), and the Back-Cover Texts are (b) (see below). (a) The FSF's Front-Cover Text is: A GNU Manual (b) The FSF's Back-Cover Text is: You have freedom to copy and modify this GNU Manual, like GNU software. Copies published by the Free Software Foundation raise funds for GNU development. i Table of Contents 1 Overview :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.1 Character sets:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.2 Initial processing ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.3 Tokenization ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 4 1.4 The preprocessing language :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 2 Header Files::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.1 Include Syntax ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.2 Include Operation :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.3 Search Path :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.4 Once-Only Headers::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.5 Alternatives to Wrapper #ifndef :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Safejava: a Unified Type System for Safe Programming

SafeJava: A Unified Type System for Safe Programming by Chandrasekhar Boyapati B.Tech. Indian Institute of Technology, Madras (1996) S.M. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1998) Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2004 °c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2004. All rights reserved. Author............................................................................ Chandrasekhar Boyapati Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science February 2, 2004 Certified by........................................................................ Martin C. Rinard Associate Professor, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Thesis Supervisor Accepted by....................................................................... Arthur C. Smith Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students SafeJava: A Unified Type System for Safe Programming by Chandrasekhar Boyapati Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on February 2, 2004, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Making software reliable is one of the most important technological challenges facing our society today. This thesis presents a new type system that addresses this problem by statically preventing several important classes of programming errors. If a program type checks, we guarantee at compile time that the program