Finally, We Have “The Tale of the Rose”, the “Beauty and the Beast” Variant Again

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Character of Zhalmauyz in the Folklore of Turkic Peoples

IJASOS- International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, Vol.II, Issue 5, August 2016 CHARACTER OF ZHALMAUYZ IN THE FOLKLORE OF TURKIC PEOPLES Pakizat Auyesbayeva1, Akbota Akhmetbekova2, Zhumashay Rakysh3* 1PhD in of philological sciences, M. O. Auezov Institute of Literature and Art, Kazakhstan, [email protected] 2PhD in of philological sciences, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Kazakhstan, [email protected] 3PhD in of philological sciences, M. O. Auezov Institute of Literature and Art, Kazakhstan, [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract Among the Turkic peoples Zhalmauyz Kempіr character, compared to other demonological characters, is widely used in genres. The transformation of this character from seven-headed villain - Zhalmauyz kempіr to mystan kempіr was seen. This very transformation is associated with the transition of society from matriarchy to patriarchy. Zhalmauyz is a syncretic person. She acts in the character of an evil old woman. This character is the main image of the evil inclination in the Kazakh mythology. She robs babies and eats them, floating on the water surface in the form of lungs, cleeks everybody who approached to the river and strangle until she will agree to give up her baby. In some tales she captures the young girls and sucks their blood through a finger deceiving or intimidating them. Two mythical characters in this fairy-tale image - mystan Kempіr and ugly villain - Zhalmauyz are closely intertwined. In the Turkic peoples Zhalmauyz generally acts as fairy-tale character. But as a specific demonological force Zhalmauyz refers to the character of hikaya genre. Because even though people do not believe in the seven-headed image of this character, but they believes that she eats people, harmful, she can pass from the human realm into the demons’ world and she is a connoisseur of all the features of both worlds. -

Knowing God 'Other-Wise': the Wise Old Woman

Knowing God “Other-wise”: The Wise Old Woman Archetype in George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin, The Princess and Curdie and “The Golden Key” Katharine Bubel “Old fables are not all a lie/That tell of wondrous birth, Of Titan children, father Sky,/And mighty mother Earth . To thee thy mother Earth is sweet,/Her face to thee is fair, But thou, a goddess incomplete,/Must climb the starry stair. Be then thy sacred womanhood/A sign upon thee set, A second baptism—understood--/For what thou must be yet.” —George MacDonald, To My Sister A consistent occurrence within the narrative archetypal pattern of The Journey is the appearance of the Wise Old Woman, a seer, encourager and advisor to those who have responded to the Call to Adventure. Such a figure is featured prominently in several of George MacDonald’s writings, though the focus of this paper is on his children’s fairy tales, The Princess and the Goblin, The Princess and Curdie, and“The Golden Key.” Since the Journey is a psychological one toward spiritual wholeness, for MacDonald, I borrow from Jungian theory to denote the Wise Old Woman as a form of anima, or female imago, who helps to develop the personality of the protagonist. But to leave things there would not encompass the sacramental particularity and universal intent of MacDonald’s fantasy: for the quest is ultimately a sacred journey that every person can make towards God. As Richard Reis writes, “If in one sense [MacDonald’s] muse was mythic- archetypal-symbolic, it was, in another way, deliberately didactic and thus ‘allegorical’ in purpose if not in achievement” (124). -

Terry Pratchett's Discworld.” Mythlore: a Journal of J.R.R

Háskóli Íslands School of Humanities Department of English Terry Pratchett’s Discworld The Evolution of Witches and the Use of Stereotypes and Parody in Wyrd Sisters and Witches Abroad B.A. Essay Claudia Schultz Kt.: 310395-3829 Supervisor: Valgerður Guðrún Bjarkadóttir May 2020 Abstract This thesis explores Terry Pratchett’s use of parody and stereotypes in his witches’ series of the Discworld novels. It elaborates on common clichés in literature regarding the figure of the witch. Furthermore, the recent shift in the stereotypical portrayal from a maleficent being to an independent, feminist woman is addressed. Thereby Pratchett’s witches are characterized as well as compared to the Triple Goddess, meaning Maiden, Mother and Crone. Additionally, it is examined in which way Pratchett adheres to stereotypes such as for instance of the Crone as well as the reasons for this adherence. The second part of this paper explores Pratchett’s utilization of different works to create both Wyrd Sisters and Witches Abroad. One of the assessed parodies are the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm as well as the effect of this parody. In Wyrd Sisters the presence of Grimm’s fairy tales is linked predominantly to Pratchett’s portrayal of his wicked witches. Whereas the parody of “Cinderella” and the fairy tale’s trope is central to Witches Abroad. Additionally, to the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales, Pratchett’s parody of Shakespeare’s plays is central to the paper. The focus is hereby on the tragedies of Hamlet and Macbeth, which are imitated by the witches’ novels. While Witches Abroad can solely be linked to Shakespeare due to the main protagonists, Wyrd Sisters incorporates both of the aforementioned Shakespeare plays. -

THE CRONE: EMERGING VOICE in a FEMININE SYMBOLIC DISCOURSE LYNNE S. MASLAND B.A., University of California, Riverside, 1970 M.A

THE CRONE: EMERGING VOICE IN A FEMININE SYMBOLIC DISCOURSE LYNNE S. MASLAND B.A., University of California, Riverside, 1970 M.A., University of California, Riverside, 1971 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTL\L FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Program in Comparative Literature) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNJ^E^ffrOFBRtTISH COLUMBIA October, 1994 ©Lynne S. Masland, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) of( Jrw^baxntiJS-^ fdkxdJruA-^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE.6 (2/88) 11 ABSTRACT The Crone: Emerging Voice in a Feminine Symbolic Discourse This dissertation explores portrayals of old women in samples drawn predominantly from French and American literature, using myth, folklore, psychological and feminist theories to examine, compare and contrast depictions of this figure through close textual analysis. I have examined treatments of old women in literary texts by Boethius, Jean de Meung, and Perrault as well as those in texts by women writers, including Sand, Colette, de Beauvoir, Jewett, Gather, Porter, Wharton, Flagg, Meigs and Silko. -

The Society for Animation Studies Newsletter

Volume 19, Issue 1 Summer 2006 The Society for Animation Studies Newsletter ISSN: 1930-191X In this Issue: Letter from the Editor Perspectives on Animation Studies Greetings! 2 ● To Animate in a Different Key As a new SAS member, I have found the Jean Detheux Society to be an active, welcoming, and 5 ● Simple Pivot Hinges for Cut-Out stimulating place where experienced and Animations young scholars alike can share their Mareca Guthrie passion for Animation Studies. 9 ● Czech Animation in 2005, An Artist's The SAS Newsletter represents a Journey supportive and convenient forum for our Brian Wells community to contribute to this growing News and Publications academic field and to get to know each other better. It offers an opportunity for 19 • Introductory Issue of Animation: an members to voice our ideas (Perspectives Interdisciplinary Journal on Animation Studies), to promote our Suzanne Buchan recent accomplishments (News and 22 • The Illusion of Life II and New Essays Publications), to learn what the SAS is Alan Cholodenko working to achieve (SAS Announcements), 24 • Between Looking and Gesturing: and to stay in touch with other members Elements Towards a Poetics of the (Membership Information). Animated Image Having no prior editorial experience, I am Marina Estela Graça deeply grateful to SAS president Maureen 25 • Frames of Imagination: Aesthetics of Furniss, webmaster Timo Linsenmaier, Animation Techniques each of this issue’s contributors, and many Nadezhda Marinchevska others for their indispensable help as I SAS Announcements navigated this exciting learning curve. As the Newsletter is only distributed to SAS 27 ● Animation at the Crossroads: 18th members, it can and ought to be tailored to SAS Conference, 7-10 July 2006 fit the needs of its select readership: you. -

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight As a Loathly Lady Tale

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as a Loathly Lady Tale By Lauren Chochinov A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2010 by Lauren Chochinov i Abstract At the end of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, when Bertilak de Hautdesert reveals Morgan le Fay’s involvement in Gawain’s quest, the Pearl Poet introduces a difficult problem for scholars and students of the text. Morgan appears out of nowhere, and it is difficult to understand the poet’s intentions for including her so late in his narrative. The premise for this thesis is that the loathly lady motif helps explain Morgan’s appearance and Gawain’s symbolic importance in the poem. Through a study of the loathly lady motif, I argue it is possible that the Pearl Poet was using certain aspects of the motif to inform his story. Chapter one of this thesis will focus on the origins of the loathly lady motif and the literary origins of Morgan le Fay. In order to understand the connotations of the loathly lady stories, it is important to study both the Irish tales and the later English versions of the motif. My study of Morgan will trace her beginnings as a pagan healer goddess to her later variations in French and Middle English literature. The second chapter will discuss the influential women in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and their specific importance to the text. -

Dreams and the Coming of Age

Dreams and The Coming of Age Harry R. Moody AARP, Academic Affairs Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, (43:2), July, 2011. It has been said that “In our dreams we are always young.” But this is true only as long as we fail to look beneath the surface of our dreams. Our dream life can offer us compelling clues about what "conscious aging" might promise for the second half of life. Psychology for the most part has focused chiefly on the first half of life , while gerontology has largely focused on decline instead of positive images of age (Biggs, 1999). Among dream researchers later life has not been a focus of attention, although the small empirical literature on this subject does offer hints for what to look for (Kramer, 2006). Here we consider dreams about aging, offering suggestions for how our dream life can give directions for a more positive vision of the second half of life. Elder Ego and Elder Ideal Our wider culture offers contrasting versions of the self in later life, what I will call here the "Elder Ego." On the one hand, we have images of vulnerable, decrepit elders—the “ill-derly,” images all too prevalent in media dominated by youth culture. On the other hand, we have an image of so-called Successful Aging, which often seems to be nothing more than an extension of youth or midlife: the “well-derly.” These opposing images-- the 'ill-derly" and the "well-derly" populate our dream life as they do our waking world. Yet these are not the only images of the Elder Ego. -

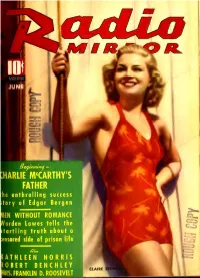

He Enthralling Success Startling Truth About A

A MACfADDEN PUBLICATION HARLIE MCCARTHY'S FATHER he enthralling success tory of Edgar Bergen EN WITHOUT ROMANCE arden Lawes tells the startling truth about a ensored side of prison life KATHLEEN NORRIS ZOBERT BENCHLEY CLAIRE RS. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT XLAN ..the "Undies*Test proves how MAVIS guards your daintiness You lure... you thrill ... when you are divinely dainty! For exquisite sweetness is the one thing a mail can't resist. And here's how you can play safe ... Every morning, shower your whole body with Mavis Talcum. It forms a fragrant, soothing film of protection that guards your daintiness. For, this amazing talcum N has a special protective quality - it prevents excess perspiration. And here's a startling test that proves it. Tomorrow morning, cover your body with Mavis Talcum ... then, make the "undies" test at night. When you undress, examine your undies carefully. You'll be amazed to find that they are practically as sweet and fresh as when you put them on in the morning. Think what this means to your peace of mind - the freshness of your undies proves that all day long you've been safe from giving offense. And once you get the daily Mavis habit, you won't have to spend that tedious time washing out your undies every night. Instead - by using Mavis Talcum every morning - you can keep your undies immacu- late for an extra day, at least. In the evening, too, use protective Mavis Talcum ... and be sure that you are exquisite always. Know that you have the bewitching, dainty fragrance that wins love .. -

Mason Flaterials Feed N0TLEY COAL & SUPPLY CO. L0WRIE DEXTER A

LEGAL PAPER OF THE TOWN OF NUTLEY . /oh XIV. No. 23. NUTLEY, N. J., SATURDAY, APRIL 17, 1909. THRUE CENTS PER COPY./ Betting of Board of Health To Talk About the Plant Wizard. street, east ftorn Franklin avenue to Pas A LATER CAR saic aveuoe, was referred to the Water The Board of Health held its regular A talk “A Viait With Luther Burbank, :re and there Committee. y ■. : - monthly meeting on Wednesday night. the Plant Wizard,’’ will be given by Mr. A Little Talk On FOR LATE RIDERS The Milton avenue petition was again Several cases of measles were reported to William J- Kinsley, at the residence of read by the (.leik. Town Attorney Reed! t Items of Genual Interest to Local exist throughout town, but not an unusual Mr. and Mrs. Kiosley on Monday after Subject fT.i " . ' examined it and decided it wasnot yet: The of (i‘ : v"’ Readers, number for this season of the year. An noon, May 3, Mr. Kinsley has had special Ask For All Night Service and Get Hour in proper ■ form. The signatures on the ordinance to establish a bureau of vital opportunities for observing the work of fy- E. J. Mitchell, of Philadelphia, Pa., Mr. Burkbank, having met the "Plant Concession. document are largely made by an X. An. ICE CREAM statistics in connection with tbe Board, jpt the Easter holidays with friends in Wizard” at the San Frandsco Flower Councilman Halsey reported to the , affidavit is required from the person who! was passed to its second reading. Final Show and upon invitation visited him at action on the proposed ordinance will be Town Coundl on Wednesday night that ^as witness to the mark made; .j A. -

Mythological Or Archetypical Theory

Mythological or Archetypical Theory This theory is all about symbols. Remember that there are three main points of study: Archetypal Characters, Archetypal Images, and Archetypal Situations. Below you will find more detailed information on these points of study. Archetypal Characters The Hero • a figure, often larger than life, whose search for identity and/or fulfillment results in his or her destruction (often accompanied by the destruction of society in general). • The aftermath of the death of the hero, however, results in progress toward some ideal. • While this applies to modern superheroes such as Superman (Clark Kent, searching for the balance between his super self and his mortal identity), it also applies figures in many religions. • Christianity’s Jesus, who must come to terms with his destiny as the Messiah, Judaism’s Moses, reluctant to fulfill his assigned destiny as the leader of the Israelites, and thousands of other literary and religious figures throughout history are examples of the archetype. • Variations of the HERO figure include the “orphaned” prince or the lost chieftain’s son raised ignorant of his heritage until he is rediscovered (King Arthur, Theseus). The Scapegoat • an innocent character on whom a situation is blamed —or who assumes the blame for a situation—and is punished in place of the truly guilty party, thus removing the guilt from the culprit and from society. The Loner or • a character who is separated fro m (or separates him or herself from) society due to either an Outcast impairment or an advantage that sets this character apart from others. Often, the Hero is an outcast at some point in his or her story. -

A Classification Scheme for Literary Characters

Psychological Thought psyct.psychopen.eu | 2193-7281 Research Articles A Classification Scheme for Literary Characters Matthew Berry a, Steven Brown* a [a] Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Abstract There is no established classification scheme for literary characters in narrative theory short of generic categories like protagonist vs. antagonist or round vs. flat. This is so despite the ubiquity of stock characters that recur across media, cultures, and historical time periods. We present here a proposal of a systematic psychological scheme for classifying characters from the literary and dramatic fields based on a modification of the Thomas-Kilmann (TK) Conflict Mode Instrument used in applied studies of personality. The TK scheme classifies personality along the two orthogonal dimensions of assertiveness and cooperativeness. To examine the validity of a modified version of this scheme, we had 142 participants provide personality ratings for 40 characters using two of the Big Five personality traits as well as assertiveness and cooperativeness from the TK scheme. The results showed that assertiveness and cooperativeness were orthogonal dimensions, thereby supporting the validity of using a modified version of TK’s two-dimensional scheme for classifying characters. Keywords: literary characters, archetypes, classification, personality, Thomas-Kilmann, assertiveness, cooperativeness Psychological Thought, 2017, Vol. 10(2), 288–302, doi:10.5964/psyct.v10i2.237 Received: 2017-06-28. Accepted: 2017-08-23. Published (VoR): 2017-10-20. Handling Editors: Marius Drugas, University of Oradea, Oradea, Romania; Stanislava Stoyanova, South-West University "Neofit Rilski", Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria *Corresponding author at: Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University, 1280 Main St. -

Dog Be with You, and Other Blessings Ryan Masters Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-10-2018 Dog Be with You, and Other Blessings Ryan Masters Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Recommended Citation Masters, Ryan, "Dog Be with You, and Other Blessings" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1288. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1288 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Creative Non-Fiction Writing Dog Be with You, and Other Blessings by Ryan Masters A thesis presented to The Graduate School of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts May 2018 St. Louis, Missouri Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………iii In Case of Apocalypse, Break Glass……………………………………………………………1 Dog Be with You……………………………………………………………………………...16 Your Body is Not Your Own………………………………………………………………….27 The Prayer of Faith Will Make You Well…………………………………………………….40 The Time of Decision…………………………………………………………………………48 Drugs are My Love Language………………………………………………………………...56 Spinning on a Wheel of Fortune………………………………………………………………65 ii Acknowledgments A special thanks to my committee, Edward McPherson, my chair, and Kathleen Finneran, co- chair. iii In Case of Apocalypse, Break Glass I had been living at the Finn House for a few years by the time Kaleb accidentally killed the dairy goat.