Historia Monachorum in Ægypto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

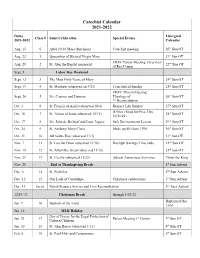

Catechist Calendar 2021-2022

Catechist Calendar 2021-2022 Dates Liturgical Class # Saint Celebration Special Events 2021-2022 Calendar Aug. 15 0 After 10:30 Mass (luncheon) Catechist meeting 20th Sun OT Aug. 22 1 Queenship of Blessed Virgin Mary 21st Sun OT FR/FC Parent Meeting: Overview Aug. 29 2 St. John the Baptist memorial 22nd Sun OT of Rec/Comm Sept. 5 Labor Day Weekend Sept. 12 3 The Most Holy Name of Mary 24th Sun OT Sept. 19 4 St. Matthew (observed on 9/21) Catechetical Sunday 25th Sun OT FR/FC \Parent Meeting: Sept. 26 5 Sts. Cosmas and Damian Theology of 26th Sun OT 1st Reconciliation Oct. 3 6 St. Francis of Assisi (observed 10/4) Respect Life Sunday 27th Sun OT (Office closed for Pres. Day Oct. 10 7 St. Teresa of Jesus (observed 10/15) 28th Sun OT 10/11/21) Oct. 17 8 Sts. John de Brébeuf and Isaac Jogues Safe Environments Lesson 29th Sun OT Oct. 24 9 St. Anthony Mary Claret Make up SE class 1 PM 30th Sun OT Oct. 31 10 All Saints Day (observed 11/1) 31st Sun OT Nov. 7 11 St. Leo the Great (observed 11/10) Daylight Savings Time ends 32nd Sun OT Nov. 14 12 St. Albert the Great (observed 11/15) 33rd Sun OT Nov. 21 13 St. Cecilia (observed 11/22) Advent Awareness Activities Christ the King Nov. 28 End of Thanksgiving Break 1st Sun Advent Dec. 5 14 St. Nicholas 2nd Sun Advent Dec. 12 15 Our Lady of Guadalupe Christmas celebrations 3rd Sun Advent Dec. -

Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of the Syriac Orthodox

Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of The Syriac Orthodox Church Volume I Fr. K. Mani Rajan, M.Sc., M.Ed., Ph.D. The Travancore Syriac Orthodox Publishers Kottayam - 686 004 Kerala, India. 2007 1 Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of The Syriac Orthodox Church (Volume I) By Fr. K. Mani Rajan, M.Sc., M.Ed., Ph.D. First Edition 2007 Copyright Reserved All rights reserved. No reproduction or translation in whole or part is allowed without written permission from the author. Price Rs. 100.00 U.S. $ 10.00 Typesetting and Cover Design by: M/s Vijaya Book House, M.G.University, Athirampuzha Printed at: Dona Colour Graphs, Kottayam Published By: The Travancore Syriac Orthodox Publishers Kottayam - 686 004 Kerala, India. Phone: +91 481 3100179, +91 94473 15914 E-mail: [email protected] Copies: 1000 2 Contents Preface Apostolic Bull of H. H. Patriarch Abbreviations used 1. St. John, the Baptist .................................................. 2. S t . S t e p h e n , t h e Martyr ................................................................................ 3. St. James, the Disciple ............................................... 4. St. James, the First Archbishop of Jerusalem ............ 5. King Abgar V of Urhoy ................................................ 6. St. Mary, the Mother of God ....................................... 7. St. Peter, the Disciple ................................................. 8. St. Paul, the Disciple .............................................................................. 9. St. Mark, the Evangelist ............................................ -

St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church: Mckinney, Texas RECTORY : (972) 529-2754 708 S

Regular Schedule PASTOR : FR. SERAPHIM HOLLAND TEMPLE ADDRESS: (see www.orthodox.net/calendar for updates and festal services) St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church: McKinney, Texas RECTORY : (972) 529-2754 708 S. CHESTNUT MCKINNEY , TEXAS Wed Vespers 7PM http://www.orthodox.net MOBILE : (972) 658-5433 75071 Thu Liturgy time varies SERAPHIM @ORTHODOX.NET Sat Confession 4PM ; Vigil 5 PM January 2009 MAILING ADDRESS : Sun Hours&Liturgy 9:40 AM, followed by a community meal open to all PO BOX 37, MCKINNEY , TX 75070 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Holy Nativity Troparion - Tone 4 Holy Theophany Troparion - Tone 1 Dec 19/Jan 1 29WAP Wine&Oil Dec 20/Jan 2 Wine&Oil Dec 21/Jan 3 Wine&Oil Holy Martyr Boniface (+ 290) HM Ignatius the God-bearer Saturday before Nativity Thy Nativity, O Christ our God,/hast shown upon the world the When Thou wast baptized in the Jordan, O Lord, /The worship of HEB 7:1-6; LK 21:28-33 HEB 7:18-25; LK 21:37-22:8 Martyr Juliana of Nicomodia light of knowledge./For, thereby they that worshipped the the Trinity wast made manifest,/for the voice of the Father bear EPH 2:11-13; LK 13:18-29; SAT BEFORE NAT :GAL 3:8-12; LK 13:18- stars/were taught by a star,/to worship Thee, the Son of witness to Thee/Calling Thee his beloved Son. /And the Spirit, in 29 Righteousness,/and to know Thee, the Day-spring from on high. the form of a dove, confirmed the certainty of the word. -

First Page Vol 4.Pmd

Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of The Syriac Orthodox Church Volume IV Cor-Episcopo K. Mani Rajan, M.Sc., M.Ed., Ph.D. J. S. C. Publications Patriarchal Centre Puthencruz 2016 Blank Dedicated to the blessed memory of Moran Mor Ignatius Zakka I Iwas (AD 1933 - 1914) Patriarch of Antioch & All the East Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of The Syriac Orthodox Church (Volume IV) Cor-Episcopo K. Mani Rajan, M.Sc., M.Ed., Ph.D. First Edition 2016 Copyright Reserved All rights reserved. No reproduction or translation in whole or part is allowed without written permission from the author. Price Rs. 90.00 U.S. $ 10.00 Typesetting and Cover Design by: Santhosh Joseph Printed at: Dona Colour Graphs, Kottayam Published By: J. S. C. Publications MD Church Centre, Patriarchal Centre Puthencruz, Kerala, India Phone: + 91 484 2255581, 3299030 Copies: 1000 iv Contents Apostolic Bull ................................................................ vii Preface ...........................................................................ix Acknowledgement ..........................................................xi Abbreviations used ........................................................ xiii 1. St. Simeon, the Aged & Morth Hannah .................. 01 2. St. Joseph of Arimathea ......................................... 03 3. St. Longinus, the Martyr......................................... 05 4. Sts.Shmuni, her seven children and Eliazar ........... 07 5. St. Evodius, The Patriarch of Antioch, Martyr .......... 11 6. St. Barnabas, the Apostle ..................................... -

Read a Sample

Our iņ ev Saints for Every Day Volume 1 January to June Written by the Daughters of St. Paul Edited by Sister Allison Gliot Illustrated by Tim Foley Boston 5521–9_interior_OFH_vol1.indd 3 12/22/20 4:45 PM Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943471 CIP data is available. ISBN 10: 0– 8198– 5521– 9 ISBN 13: 978– 0- 8198– 5521– 3 The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Re- vised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition, copyright © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover and interior design by Mary Joseph Peterson, FSP Cover art and illustrations by Tim Foley All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechan- ical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. “P” and PAULINE are registered trademarks of the Daughters of St. Paul. Copyright © 2021, Daughters of St. Paul Published by Pauline Books & Media, 50 Saint Pauls Avenue, Boston, MA 02130– 3491 Printed in the USA OFIH1 VSAUSAPEOILL11-1210169 5521-9 www.pauline.org Pauline Books & Media is the publishing house of the Daughters of St. Paul, an international congregation of women religious serving the Church with the communications media. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 25 24 23 22 21 5521–9_interior_OFH_vol1.indd 4 12/14/20 4:12 PM We would like to dedicate this book to our dear Sister Susan Helen Wallace, FSP (1940– 2013), author of the first edition of Saints for Young Readers for Every Day. -

Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of the Syriac Orthodox Church

Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of The Syriac Orthodox Church Volume VII Cor-Episcopo K. Mani Rajan, M.Sc., M.Ed., Ph.D. J. S. C. Publications Patriarchal Centre Puthencruz 2019 Dedicated to St. Osthatheos Sleeba (AD 1908 - 1930) Delegate of the Holy See of Antioch Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of The Syriac Orthodox Church (Volume VII) Cor-Episcopo K. Mani Rajan First Edition 2019 Copyright Reserved All rights reserved. No reproduction or translation in whole or part is allowed without written permission from the author. Price Rs. 95.00 U.S. $ 10.00 Typesetting and Cover Design by: Julius C. Abraham, megapixel Graphics, Kottayam Printed at: Mor Julius Press, Puthencruz Published By: J. S. C. Publications MD Church Centre, Patriarchal Centre Puthencruz, Kerala, India Phone: + 91 484 2255581, 9400306581 email:[email protected] Copies: 1000 Contents Foreword ................................................. vii Acknowledgement .................................... ix Abbreviations Used .................................. xi 1. Apostle Aquila ................................................1 2. Saint Christina ................................................2 3. Prophet Micah ................................................5 4. Saint Eutychius, Disciple of Apostle John .....6 5. Gregory of Nazianzus, the Elder ....................7 6. Mor Gregorius Paulos Behnam .....................8 7. Hananiah who baptised St. Paul ...................10 8. Lydia, who sold purple cloth ........................12 9. Nicodemus ...................................................14 -

Our Lady of Victories Church (Serving Harrington Park, River Vale and the Pascack/Northern Valley) 150 Harriot Avenue, Harrington Park, New Jersey

Our Lady of Victories Church (serving Harrington Park, River Vale and the Pascack/Northern Valley) 150 Harriot Avenue, Harrington Park, New Jersey www.olvhp.org S˞˗ˍˊˢ, March 22, 2020 A.D. WELCOME 4th SUNDAY OF LENT To the Parish Family of OUR LADY OF VICTORIES (THE LITTLE CHURCH WITH THE BIG HEART) COME WORSHIP WITH US Rev. Wojciech B. Jaskowiak Pastor Mr. Thomas Lagatol Mr. Albert McLaughlin Deacons PARISH OFFICE Maria Hellrigel - Parish Secretary 201-768-1706 Religious Education (CCD) Susan Evanella Denise Coulter (LSEC) 201-768-1400 Sr. Elizabeth Holler, SC Sr. Mary Corrigan, SC In Residence-Convent Selena Piazza Elizabeth Gulfo Lesa Rossmann Martin Coyne II Ministers of Music Parish Trustees Jorden Pedersen Esq. Jon Fischer CFA President Parish Council Chairman Finance Committee THE SACRAMENT OF PENANCE/CONFESSION: Monday - Friday 7:30am - 7:50am. First Friday at 6:00pm - 6:50pm Special Masses: Saturday at 11:00a.m.-Noon; 3:00pm –3:40pm First Friday: 6:00pmConfessionsfollowed byDevotions & Mass First Saturday: 8:00am Mass of Immaculate Heart of Mary THE SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM: To register for Baptismal preparation and Baptism, First Saturday: 12:00pm Mass for Souls in Purgatory call the rectory. THE SACRAMENT OF CONFIRMATION: Novenas prayed after 8:00 a.m. Mass: Call the Religious Ed Office for requirements/class schedule. Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal: Monday THE SACRAMENT OF MATRIMONY: St. Jude and St. Anthony: Wednesday Please call the rectory for an appointment. Infant of Prague: 25th of the month 2THE SACRAMENT OF THE SICK/LAST RITES: Sick calls at any time in emergency. -

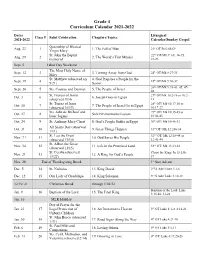

Grade 4 Curriculum Calendar 2021-2022

Grade 4 Curriculum Calendar 2021-2022 Dates Liturgical Class # Saint Celebration Chapters/Topics 2021-2022 Calendar/Sunday Gospel Queenship of Blessed Aug. 22 1 1. The Fall of Man 21st OT/Jn 6:60-69 Virgin Mary St. John the Baptist 22nd OT/Mk 7:1-8, 14-15, Aug. 29 2 2. The World’s First Murder memorial 21-23 Sept. 5 Labor Day Weekend The Most Holy Name of Sept. 12 3 3. Turning Away from God 24th OT/Mk 8:27-35 Mary St. Matthew (observed on 4. God Prepares a People for the Sept. 19 4 25th OT/Mk 9:30-37 9/21) Savior 26th OT/Mk 9:38-43, 45, 47- Sept. 26 5 Sts. Cosmas and Damian 5. The People of Israel 48 St. Francis of Assisi 27th OT/Mk 10:2-16 or 10:2- Oct. 3 6 6. Joseph Goes to Egypt (observed 10/4) 12 St. Teresa of Jesus 28th OT/ Mk 10:17-30 or Oct. 10 7 7. The People of Israel Go to Egypt (observed 10/15) 10:17-27 Sts. John de Brébeuf and 29th OT/ Mk 10:35-45 or Oct. 17 8 Safe Environments Lesson Isaac Jogues 10:42-45 Oct. 24 9 St. Anthony Mary Claret 8. God’s People Suffer in Egypt 30th OT/ Mk 10:46-52 All Saints Day (observed Oct. 31 10 9. Great Things Happen 31st OT/ Mk 12:28b-34 11/1) St. Leo the Great 32nd OT/ Mk 12:38-44 or Nov. 7 * 11 10. -

Renowned Ascetics: Their Lives & Practices

Renowned Ascetics: Their Lives & Practices Cor-Episcopo K. Mani Rajan, M.Sc., M.Ed., Ph.D. J. S. C. Publications Patriarchal Centre Puthencruz 2017 Renowned Ascetics: Their Lives & Practices Cor-Episcopo K. Mani Rajan First Edition 2017 Copyright Reserved All rights reserved. No reproduction or translation in whole or part is allowed without written permission from the author. Price Rs. 95.00 U.S. $ 5.00 Typesetting and Cover Design by: Julius C. Abraham, megapixel Graphics, Kottayam Printed at: Mor Julius Press, Puthencruz Published By: J. S. C. Publications MD Church Centre, Patriarchal Centre Puthencruz, Kerala, India Phone: + 91 484 2255581, 3299030 Copies: 1000 Contents Author’s Preface ............................................v Acknowledgement ........................................xv Abbreviations Used ....................................xvii 1. St. Cyprian, the Martyr ................................. 1 2. St. Malke ...................................................... 3 3. St. Paul of Thebaid ........................................ 5 4. St. Antony of Egypt ...................................... 8 5. St. Aphrahat, the Ascetic ..............................11 6. St. Ammon (Amus) of Nitria ..................... 14 7. St. Pachomius, the hermit ........................... 17 8. St. Hilarion, the Abbot ................................ 20 9. Abraham Kidunay ....................................... 23 10. St. Dimet of Persia ...................................... 25 11. St. Macarius of Egypt ................................. 27 -

P.Oxy. 33.2673 Malcolm Choat and Rachel Yuen-Collingridge

THE BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PapYROLOGIsts Volume 46 2009 Editorial Committee: Peter van Minnen Timothy Renner, John Whitehorne Advisory Board: Antti Arjava, Paola Davoli, Gladys Frantz-Murphy, Andrea Jördens, David Martinez, Kathleen McNamee, John Tait, David Thomas, Dorothy Thompson, Terry Wilfong Copyright © The American Society of Papyrologists 2009 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Contents Alan Edouard Samuel (1932-2008) .......................................................................7 A Fragment of Homer, Iliad 21 in the Newberry Library, Chicago Sofía Torallas Tovar and Klaas A. Worp ......................................................11 A Latin Manumission Tax Tablet in Los Angeles Peter van Minnen and Klaas A. Worp .........................................................15 Report of Proceedings in Red Ink from Late Second Century AD Oxyrhynchus Lincoln H. Blumell ..........................................................................................23 Two Papyri in Lund Todd M. Hickey ..............................................................................................31 Two Michigan Papyri Jennifer Sheridan Moss ..................................................................................37 Letter from Simades to Pynas Athanassios Vergados .....................................................................................59 Annotazioni sui Fragmenta Cairensia delle Elleniche di Ossirinco Gianluca Cuniberti .........................................................................................69 -

Why Do Catholics Call Good Friday

Discovering hope and joy in the Catholic faith. March 2020 ST. THOMAS THE APOSTLE PARISH StThomasWestSpringfield.org Dealing with difcult people Jesus’ way People who argue, ght, or refuse are able or willing to give, yet we give to cooperate can make our lives in out of guilt or fear of displeasure. St. Toribio de Mogrovejo downright miserable. Yet, Jesus was Two of his best friends, James Born in Mayorga, masterful at dealing with difcult and John, said to Jesus, “we Spain, St. Toribio was people. Following his example want you to do whatever we ask educated in law can save our sanity and of you” (Mark 10:35). In and became our relationships. response to this stunning the Professor Know when to breach of boundaries, Jesus of Law at ignore. When Jesus was calm and rm. He said Salamanca made his Nazareth “no” and didn’t University. His friends and second-guess himself work and his holiness earned neighbors so mad when he didn’t make his him the notice of the king, that they wanted to loved ones happy. who named him to be the throw him off a cliff, Know when to stay next Archbishop of Lima. he knew there was no calm. When Jesus took a Despite his arguments, Toribio reasoning with them. Sabbath stroll with his was ordained a priest, “Passing through the friends (Matthew 12), consecrated, and sent to Peru. midst of them he went Pharisees barged in and He spent his ofce reforming away” (Luke 4:30). When people accused him of breaking the the then-corrupt diocese, speak harshly or offensively, the best Sabbath. -

March 21, 2021 A.D

Our Lady of Victories Church (serving Harrington Park, River Vale and the Pascack/Northern Valley) Harrington Park, New Jersey www.olvhp.org Sunday, March 21, 2021 A.D. Fifth Sunday of Lent WELCOME In the Year of Saint Joseph To the Parish Family of OUR LADY OF VICTORIES (THE LITTLE CHURCH WITH THE BIG HEART) Parish Office 201-768-1706 COME WORSHIP WITH US Rev. Wojciech B. Jaskowiak Pastor Rev. Edmond P. Ilg Parochial Vicar Mr. Thomas Lagatol Mr. Albert McLaughlin Deacons Lenten Confession Schedule (in lower church) Mon-Fri March 22 - 26 7:30AM - 7:50AM Saturday March 27 – All Day 7:30AM - 6:00PM Palm Sunday March 28 – All Day Novenas prayed after 8:00 a.m. Mass: 6:30AM - 7:00PM Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal: Monday St. Jude and St. Anthony: Wednesday THE SACRAMENT OF CONFESSION: Infant of Prague: 25th of the month Mon.-Sat.: 7:30-7:50am. Saturday: 11:00-11:50am; 3:00-3:45pm St. Peregrine: First Friday of the Month THE SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM: To register for Baptismal preparation and Baptism, call the rectory. Rosary: Recited M - Sat after 8:00am & after 12:00Noon Mass THE SACRAMENT OF CONFIRMATION: Call the Religious Ed Office for requirements/class schedule. THE SACRAMENT OF MATRIMONY: Please call the rectory for an appointment. STATIONS OF THE CROSS THE SACRAMENT OF THE SICK/LAST RITES: Sick calls at any time in emergency. during Lent THE SACRAMENT OF HOLY ORDERS AND VOCATIONS: EVERY FRIDAY: 11:30AM & 7:00PM –in Church Anyone contemplating a vocation to the Priesthood or Religious Life should contact the Vocations Office at 973.497.4365.