Renowned Ascetics: Their Lives & Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church Houston, Texas

A Glimpse Into The Coptic World Presented by: St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church Houston, Texas www.stmaryhouston.org © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX Slide 1 A Glimpse Into The Coptic World © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX Slide 2 HI KA PTAH © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX The word COPT is derived from the ancient Egyptian word HI KA PTAH meaning house of spirit of PTAH. According to ancient Egyptians, PTAH was the god who molded people out of clay and gave them the breath of life; This believe relates to the original creation of man. The Greeks changed the name of “HI KA PTAH “ to Ai-gypt-ios. © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX Slide 3 © St. Mary & ArchangelAncient Michael Coptic Egypt Orthodox Church, Houston, TX The Arabs called Egypt DAR EL GYPT which means house of GYPT; changing the letter g to q in writing. Originally all Egyptians were called GYPT or QYPT, but after Islam entered Egypt in the seventh century, the word became synonymous with Christian Egyptians. According to tradition, the word MISR is derived from MIZRA-IM who was the son of HAM son of NOAH It was MIZRA-IM and his descendants who populated the land of Egypt. © St. Mary & Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church, Houston, TX Slide 4 © St. Mary The& Archangel Coptic Michael Coptic language Orthodox Church, Houston, TX The Coptic language and writing is the last form of the ancient Egyptian language, the first being Hieroglyphics, Heratic and lastly Demotic. -

Nil Sorsky: the Authentic Writings Early 18Th Century Miniature of Nil Sorsky and His Skete (State Historical Museum Moscow, Uvarov Collection, No

CISTER C IAN STUDIES SERIES : N UMBER T WO HUNDRED T WENTY -ONE David M. Goldfrank Nil Sorsky: The Authentic Writings Early 18th century miniature of Nil Sorsky and his skete (State Historical Museum Moscow, Uvarov Collection, No. 107. B 1?). CISTER C IAN STUDIES SERIES : N UMBER T WO H UNDRED TWENTY -ONE Nil Sorsky: The Authentic Writings translated, edited, and introduced by David M. Goldfrank Cistercian Publications Kalamazoo, Michigan © Translation and Introduction, David M. Goldfrank, 2008 The work of Cistercian Publications is made possible in part by support from Western Michigan University to The Institute of Cistercian Studies Nil Sorsky, 1433/1434-1508 Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Nil, Sorskii, Saint, ca. 1433–1508. [Works. English. 2008] Nil Sorsky : the authentic writings / translated, edited, and introduced by David M. Goldfrank. p. cm.—(Cistercian studies series ; no. 221) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 978-0-87907-321-3 (pbk.) 1. Spiritual life—Russkaia pravoslavnaia tserkov‚. 2. Monasticism and religious orders, Orthodox Eastern—Russia—Rules. 3. Nil, Sorskii, Saint, ca. 1433–1508—Correspondence. I. Goldfrank, David M. II. Title. III. Title: Authentic writings. BX597.N52A2 2008 248.4'819—dc22 2008008410 Printed in the United States of America ∆ Estivn ejn hJmi'n nohto;~ povlemo~ tou' aijsqhtou' calepwvtero~. ¿st; mysla rat;, vnas= samäx, h[v;stv÷nyã l[täi¡wi. — Philotheus the Sinaite — Within our very selves is a war of the mind fiercer than of the senses. Fk 2: 274; Eparkh. 344: 343v Table of Contents Author’s Preface xi Table of Bibliographic Abbreviations xvii Transliteration from Cyrillic Letters xx Technical Abbreviations in the Footnotes xxi Part I: Toward a Study of Nil Sorsky I. -

GLIMPSES INTO the KNOWLEDGE, ROLE, and USE of CHURCH FATHERS in RUS' and RUSSIAN MONASTICISM, LATE 11T H to EARLY 16 T H CENTURIES

ROUND UP THE USUALS AND A FEW OTHERS: GLIMPSES INTO THE KNOWLEDGE, ROLE, AND USE OF CHURCH FATHERS IN RUS' AND RUSSIAN MONASTICISM, LATE 11t h TO EARLY 16 t h CENTURIES David M. Goldfrank This essay originated at the time that ASEC was in its early stages and in response to a requestthat I write something aboutthe church Fathers in medieval Rus'. I already knew finding the patrology concerning just the original Greek and Syriac texts is nothing short of a researcher’s black hole. Given all the complexities in volved in the manuscript traditions associated with such superstar names as Basil of Caesarea, Ephrem the Syrian, John Chrysostom, and Macarius of wherever (no kidding), to name a few1 and all of The author would like to thank the staffs of the Hilandar Research Library at The Ohio State University and, of course, the monks of Hilandar Monastery for encouraging the microfilming of the Hilandar Slavic manuscripts by Ohio State. I thank the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection; and Georgetown University’s Woodstock Theological Library as well as its Lauinger Library Reference Room for their kind help. Georgetown University’s Office of the Provost and Center for Eurasian, East European and Russian Studies provided summer research support. Thanks also to Jennifer Spock and Donald Ostrowski for their wise suggestions. 1 An excellent example of this is Plested, Macarian Legacy. For the spe cific problem of Pseudo-Macarius/Pseudo-Pseudo-Macarius as it relates to this essay, see NSAW, 78-79. Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture. -

Abraham (Hermit) 142F. Aristode 160 Acacius (Bishop Atarbius (Bishop Of

INDEX Abraham (hermit) 142f. Aristode 160 Acacius (bishop Atarbius (bishop of Caesarea) 80f., 86f., of Neocaesarea) 109f., 127 91 Athanasius 63, 67ff., 75 Acacius (bishop Athanasius of Balad 156, 162 of Beroea) 142ff. Athenodorus (brother Aelianus 109 of Gregory al-Farabi 156 Thaumaturgus) 103, 105, Alexander (bishop 133 of Comana) I 26f., 129, Athens 120 132 Augustine 9-21, 70 Alexander (of the Cassiciacum Dialogues 9, 15ff. "Non-Sleepers" Corifessions 9-13, 15, monastery) 203, 211 18, 20f. Alexander (patriarch De beata vita 16ff. of Antioch) 144 De ordine 16ff. Alexander of Retractions 19 Abonoteichos 41 Soliloquies 19f. Alexander Severus Aurelian (emperor (emperor 222-235) 47 270-275) 121 Alexandria 37, 39f., 64, Auxentios 205 82, 101, 104, 120, Babai 172 n. II, 126f., 129 173ff. n. 92, 143, Babylas 70 156, 215 Baghdad 156 Alexandrian Christology 68 Bardesanism/Bardesanites 147 Amaseia 128 Barhadbeshabba 'Arbaya 145 Ambrose 70, 91 Barnabas 203 n. 39 Basil of Caeserea 109f., 117, Anastasios (monk) 207 121ff., 126f., Anastasius (= Magundat) 171 131, 157, Ancyra 113 166 Andrew Kalybites 207 Basilides 32, 37ff. Andrew the Fool 203 Beroea 141, 142 Annisa 112f. Berytus 101, 103f., Antioch 82, 105, 120 I I If., 155, 160, 215 Caesarea (Cappadocia) 129 Antiochene theology 72f., 143 Caesarea (Palestine) 80ff., 87, Antiochos the African 205 91, 92, 100, Antony 63,69f., 101, 103ff., 75f. 120 Antony / Antoninus Cappadocia 46ff., 53, (pupil of Lucian) 65 122 Apelles 51 Carpocrates 32, 39, 41 Arius/ Arianism/ Arians 65ff., 80ff., Carthage 47,49, 51, 92, 148 53ff., 57f. 224 INDEX Cataphrygian(s) 50ff., 56, 59 David of Thessalonike 205 Chaereas (comes) 140 Dcmosthenes (vicarius Chalcedon 75 of Pontica) III Chosroes II 17Iff., 175, Diogenes (bishop 177, I 79f., of Edessa) 144 182, 184, Dionysius (pope 259~269) 106 188 Doctrina Addai 91 n. -

St Athanasius Bulletin 15.12.13 30Th SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST

THE Light of the East St. Athanasius the Great Byzantine Catholic Church 1117 South Blaine Ave. Indianapolis, IN 46221 Website: www.saindy.com Email: [email protected] Served by: Pastor: Very Rev. Protopresbyter Bryan R. Eyman. D. Min. D. Phil. Cantors: Marcus Loidolt, John Danovich Business Manager: John Danovich Phones: Rectory: 317-632-4157; Pastor’s Cell Phone: 216-780-2555 FAX: 317-632-2988 WEEKEND DIVINE SERVICES Sat: 5 PM [Vespers with Liturgy] Sun: 9:45 AM [Third Hour] 10 AM [Divine Liturgy] Mystery of Holy Repentance [Confessions]: AFTER Saturday Evening Prayer or ANYTIME by appointment SERVICES FOR THE WEEK OF DECEMBER 15, 2013 THIRTIETH SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST. SUNDAY OF THE FOREFATHERS. The Holy Martyr Eleutherius. Our Ven. Fr. Paul of Latra. Our Holy Father Stephen, Archbishop of Surozh. PLEASE COME FORWARD AFTER THE DIVINE LITURGY; KISS THE HOLY ICONS, KISS THE HAND CROSS [OR RECEIVE THE HOLY ANOINTING], & PARTAKE OF THE ANTIDORAN [BLESSED BREAD]. SAT. DEC. 14 5 PM VESPER LITURGY Int. of Nichole Richards SUN. DEC. 15 9:45 AM THE THIRD HOUR 10 AM FOR THE PEOPLE 11:15 AM COFFEE SOCIAL [IN ST. MARY’S HALL] 11: 30 AM EPARCHICAL ASSEMBLY PRESENTATION #3 MON. DEC. 16 The Holy Prophet Haggai. NO DIVINE SERVICES~FATHER’S DAY OFF TUE. DEC. 17 The Holy Prophet Daniel and the Three Holy Children Hananiah, Azariah and Mishael. 9 AM Intention of Captain Brian Hewko WED. DEC. 18 The Holy Martyr Sebastian & His Companions. 7 PM EMANUEL MOLEBEN & MYSTERY OF HOLY ANOINTING [ANCIENT HEALING SERVICE] THU. DEC. 19 The Holy Martyr Boniface. -

The Forerunner

The Forerunner weekly bulletin of St. John the Baptist Orthodox Church Orthodox Church in America (OCA) – Archdiocese of Pittsburgh 601 Boone Avenue, Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-8216 – www.frunner.org – www.facebook.com/frunneroca/ Preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Canonsburg, the Chartiers Valley, Washington, and Beyond! January 17th, AD 2021 32nd Sunday after Pentecost (Tone 7)/12th Sunday of Luke St. Anthony the Great Home Parish of the Ever-Memorable Met. Theodosius, (+10/19) May his memory be eternal! Вѣчная память! Rector, Fr. John Joseph Kotalik 425-503-2891 – [email protected] Attached Clergy: Protodeacon John Oleynik, 724-366-0678 Deacon Theodosius Onest, 724-809-3491 Parish President & Warden, Mr. Kiprian Yarosh, 724-743-0231 Interim Choir Director, Mrs. Diane Yarosh; Cantor, Lara Galis The Orthodox Church humbly claims to be the One Church of Jesus Christ, founded on the Apostolic Witness to our Lord, born on the day of Pentecost, and for 2,000 years making known to men, women, and children the path to salvation through repentance and faith in Christ. All Services are Live-Streamed Online on our YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/c/StJohntheBaptistOrthodoxChurchCanonsburg/live Upcoming Schedule January 19, Tuesday: -7:00 PM, All-OCA Online Church School for Middle and High School Students: Every Tuesday, go to https://www.oca.org/ocs and click your age group! January 21, Thursday: FR. JOHN & MAT. JANINE RETURNING January 23, Saturday: -5:15 PM, General Pannikhida -6:00 PM, Vespers & Confession January 24, Sunday (New Martyrs & Confessors of Russia; Xenia of Petersburg; Sanctity of Life Sunday): -8:45 – 9:15 AM, Confession -9:30 AM, Divine Liturgy Church Open Until Noon -6:00 PM, Moleben to St. -

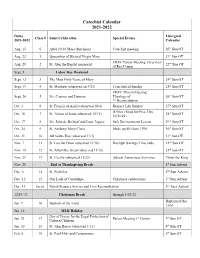

Catechist Calendar 2021-2022

Catechist Calendar 2021-2022 Dates Liturgical Class # Saint Celebration Special Events 2021-2022 Calendar Aug. 15 0 After 10:30 Mass (luncheon) Catechist meeting 20th Sun OT Aug. 22 1 Queenship of Blessed Virgin Mary 21st Sun OT FR/FC Parent Meeting: Overview Aug. 29 2 St. John the Baptist memorial 22nd Sun OT of Rec/Comm Sept. 5 Labor Day Weekend Sept. 12 3 The Most Holy Name of Mary 24th Sun OT Sept. 19 4 St. Matthew (observed on 9/21) Catechetical Sunday 25th Sun OT FR/FC \Parent Meeting: Sept. 26 5 Sts. Cosmas and Damian Theology of 26th Sun OT 1st Reconciliation Oct. 3 6 St. Francis of Assisi (observed 10/4) Respect Life Sunday 27th Sun OT (Office closed for Pres. Day Oct. 10 7 St. Teresa of Jesus (observed 10/15) 28th Sun OT 10/11/21) Oct. 17 8 Sts. John de Brébeuf and Isaac Jogues Safe Environments Lesson 29th Sun OT Oct. 24 9 St. Anthony Mary Claret Make up SE class 1 PM 30th Sun OT Oct. 31 10 All Saints Day (observed 11/1) 31st Sun OT Nov. 7 11 St. Leo the Great (observed 11/10) Daylight Savings Time ends 32nd Sun OT Nov. 14 12 St. Albert the Great (observed 11/15) 33rd Sun OT Nov. 21 13 St. Cecilia (observed 11/22) Advent Awareness Activities Christ the King Nov. 28 End of Thanksgiving Break 1st Sun Advent Dec. 5 14 St. Nicholas 2nd Sun Advent Dec. 12 15 Our Lady of Guadalupe Christmas celebrations 3rd Sun Advent Dec. -

Bulgakov Handbook

December 11 E. Our Venerable Father Daniel the Stylite Born in Samosata, Mesopotamia, he left for a certain monastery to practice asceticism at 13 years of age where he soon surprised the strict ascetics by his zealousness for prayer and diligence. Then he visited the Ven. Simeon the Stylite (see Sept. 1) and with his blessing left for a hermitage in Thrace where he climbed on a pillar about the year 459. Here he “underwent all ferocity”, “both bitterly cold winters and the heat of the sun, and the rottenness of flesh, and from it were worms of animosity”. His holy way of life frequently led the Emperors Leo and Zeno to him for the reception of his blessing and the hearing of his prophecy, always with justified events. Glorified by the gift of wonderworking and insight, St. Daniel died in the year 480. Kontakion, tone 8 Having ascended the pillar like a radiant star, O blessed One, You illumined the world with your venerable deeds, And dispelled the darkness of deception, O Father, Therefore we beseech you: Shine forth even now the never setting light of understanding Into the hearts of your servants Ven. Luke, the new Stylite A warrior, miraculously saved from death in battle with the Bulgars, he left the vain world and accepted monasticism. Ordained a presbyter, he practiced asceticism on a pillar for 45 years in the city of Chalcedon. In order to observe the vow of silence Ven. Luke carried a stone in his mouth. He died in about the year 970-980. Ven. -

Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of the Syriac Orthodox

Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of The Syriac Orthodox Church Volume I Fr. K. Mani Rajan, M.Sc., M.Ed., Ph.D. The Travancore Syriac Orthodox Publishers Kottayam - 686 004 Kerala, India. 2007 1 Martyrs, Saints & Prelates of The Syriac Orthodox Church (Volume I) By Fr. K. Mani Rajan, M.Sc., M.Ed., Ph.D. First Edition 2007 Copyright Reserved All rights reserved. No reproduction or translation in whole or part is allowed without written permission from the author. Price Rs. 100.00 U.S. $ 10.00 Typesetting and Cover Design by: M/s Vijaya Book House, M.G.University, Athirampuzha Printed at: Dona Colour Graphs, Kottayam Published By: The Travancore Syriac Orthodox Publishers Kottayam - 686 004 Kerala, India. Phone: +91 481 3100179, +91 94473 15914 E-mail: [email protected] Copies: 1000 2 Contents Preface Apostolic Bull of H. H. Patriarch Abbreviations used 1. St. John, the Baptist .................................................. 2. S t . S t e p h e n , t h e Martyr ................................................................................ 3. St. James, the Disciple ............................................... 4. St. James, the First Archbishop of Jerusalem ............ 5. King Abgar V of Urhoy ................................................ 6. St. Mary, the Mother of God ....................................... 7. St. Peter, the Disciple ................................................. 8. St. Paul, the Disciple .............................................................................. 9. St. Mark, the Evangelist ............................................ -

Sunday of the Myrrbearing Women Third Sunday of Pascha

Sunday of the Myrrbearing Women Third Sunday of Pascha 2 / 15 May 2016 Resurrection Tropar, Tone 2: When Thou didst descend to death, O Life Immortal, Thou didst slay hell with the splendour of Thy Godhead! And when from the depths Thou didst raise the dead, all the powers of Heaven cried out: O Giver of Life, Christ our God, Glory to Thee. Tropar of the Sunday Of The Myrrh-bearing Women, Tone 2: The noble Joseph took Thine immaculate Body down from the Tree, / havinG wrapped It in pure linen and spices, laid in a new tomB. / But on the third day Thou didst rise, O Lord, // GrantinG to the world Great mercy. Kondak of the Sunday Of The Myrrh-bearing Women, Tone 2: When Thou didst cry, Rejoice, unto the myrrh-bearers,/ Thou didst make the lamentation of Eve the first mother to cease / By Thy Resurrection, O Christ God. / And Thou didst Bid Thine apostles to preach: // The Saviour is risen from the Grave. Kondak of Pascha, Tone 8: Though Thou didst descend into the Grave, O Immortal One, yet didst Thou destroy the power of Hades, and didst arise as victor, O Christ God, calling to the myrrh-bearing women, Rejoice, and givinG peace unto Thine Apostles, O Thou Who dost grant resurrection to the fallen. Matins Gospel III Epistle: St. Acts of the Apostles 6: 1-7 Now in those days, when the numBer of the disciples was multiplyinG, there arose a complaint aGainst the HeBrews By the Hellenists, Because their widows were neGlected in the daily distriBution. -

Confirmation

CONFIRMATION December 1, 2020 Dear Parents and Students, You have elected to register your son/daughter for the St. Agnes Christian Formation program this year. When registering your son/daughter it is stated that our Confirmation program is a two-year program. This program challenges him or her to grow in his or her understanding of the Catholic faith and his or her personal relationship with God. There are several points to make you aware of in preparation for Confirmation (which starts in 8th grade with the student receiving the Sacrament with the completion of 9th grade studies) (due to pandemic this school year completion of 10th grade)). Successful completion of the curriculum includes once a month catechesis, service to others, and spending time with God in prayer. The greatest form of prayer is the celebration of the Mass. As Catholics, we are encouraged to attend weekly Mass in order to recognize God’s love more fully in the Word and Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. While the pandemic poses a particular challenge at this time, students and their families are highly encouraged to either attend weekly Mass in person (Precautions are in place to ensure everyone’s safety) or to seek out an online Mass to encourage growth in love for Christ in preparation for Confirmation. Below is a list of other expectations. Remember, these “assignments” are designed to support our students in their desire to know, love, and serve our wonderful God while helping to prepare them for the reception of the Sacrament. This process for being Confirmed in the Spirit is a commitment from the parish, support from parents, and a commitment from the student that wishes to be Confirmed.