The Building Pathology of Early Modern London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Ironmonger Lane, EC2V 8EY Superb Small Office Suite 646 Sq Ft Offered Fully Fitted and Furnished – Plug & Play New Lease by Arrangement @ £55.00 Per Sq Ft

20 Ironmonger Lane, EC2V 8EY Superb small office suite 646 sq ft Offered fully fitted and furnished – Plug & play New lease by arrangement @ £55.00 per sq ft Location Ironmonger Lane is a particularly tranquil, cobble stoned street that lies between Cheapside and Gresham Street, located in the heart of the City of London and very close to The Bank of England. Bank Underground Station (Central, Northern, DLR, Circle, District and Waterloo & City Lines is less than 300 meters away. Other stations including St Paul’s, Cannon Street, Moorgate and Liverpool Street are also close by. Cheapside is one of the City’s principle retailing destinations offering a diverse range of retail, restaurants and cafes. Description 20 Ironmonger Lane is a very attractive brick fronted property located on the west side of the street, with the accommodation comprising an excellent, self-contained fourth floor suite totaling 646 sq ft approx. (60 sq m). The premises are offered fully fitted and furnished if required, being arranged to provide a waiting area, boardroom, open plan area providing desks/seating for eight people and, a kitchenette. An extensive range of office IT equipment, furniture and fittings is offered. Amenities New comfort cooling Fully fitted & furnished Meeting room Kitchenette Open plan desks/seating for eight Superb natural light Video entry system Passenger lift LED suspended lighting Male & female toilet facilities Bike storage & shower facilities Perimeter trunking Terms A new lease is available on an effective full repairing and insuring basis for a term by arrangement at a quoting rent of £35,500 per annum exclusive - £54.95 per sq ft. -

With Julia Woodman

TESSELATIONTHE THREE-DIMENSIONAL FORM OCTOBER WORKSHOP METALSOCIETY OF SOUTHERN ARTS CALIFORNIA Sept Oct 2013 with Julia Woodman October 19th & 20th, 2013 Saddleback Community College in Mission Viejo $195 for MASSC members / $220 for non members Learn a new skill using metalsmithing tools, bolts and an industrial punch. That’s all that’s needed to form small silver discs, squares, jump rings, etc., into 3-D shapes suitable for bracelets, earrings or spoon handles. Students are shown how to experiment with these and more to create beautifully textured miniature sculpture to adorn or for décor. Some soldering, sawing and filing skills are needed to learn this fun, new technique – TESSELLATION. So bring your imagination and an Optivisor and let’s PLAY!! www.juliawoodman.com NEWSLETTER OCTOBER WORKSHOP TESSELATIONTHE THREE-DIMENSIONAL FORM “My work using 3D tessellation for serving utensils shows clean simple lines Julia Woodman has lived in Lahti, Finland where she studied with third and with ornate texture, almost a by-product of the technique itself.” fourth generation Fabergé masters while on a Fulbright Grant and was certified Master Silversmith in Finland, the first American. She has a MFA degree from Woodman uses tessellation to construct handles for serving pieces, arms and Georgia State University and has studied with Heikki Seppä and other masters upright portions of crosses for churches, and stems and bases for cups, trophies at the Penland School of Craft during many summer sessions. Also, she teaches and other vessels. Utility and function are major components of her work: the at the Spruill Center for the Arts in Atlanta, Chastain Arts Center and substitute teapots must work and fish slices must serve fish. -

Different Faces of One ‘Idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek

Different faces of one ‘idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek To cite this version: Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek. Different faces of one ‘idea’. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow. A systematic visual catalogue, AFM Publishing House / Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM, 2016, 978-83-65208-47-7. halshs-01951624 HAL Id: halshs-01951624 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01951624 Submitted on 20 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow A systematic visual catalogue Jean-Yves BLAISE Iwona DUDEK Different faces of one ‘idea’ Section three, presents a selection of analogous examples (European public use and commercial buildings) so as to help the reader weigh to which extent the layout of Krakow’s marketplace, as well as its architectures, can be related to other sites. Market Square in Krakow is paradoxically at the same time a typical example of medieval marketplace and a unique site. But the frontline between what is common and what is unique can be seen as “somewhat fuzzy”. Among these examples readers should observe a number of unexpected similarities, as well as sharp contrasts in terms of form, usage and layout of buildings. -

PRESS RELEASE the Goldsmiths' Company Becomes a Founding

PRESS RELEASE The Goldsmiths’ Company becomes a Founding Partner of the new Museum of London and pledges £10m donation Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Cup, designed by Goldsmith R.Y. Goodden in 1953 is pictured in the Corporation of London’s current salt store, which by 2022 will have been transformed into galleries at the new Museum of London in West Smithfield with the Thameslink track running through them. Image © Museum of London. Collection: The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths. The Museum of London and the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths (one of the major City Livery Companies) today announced that the Goldsmiths' Company is to become a Founding Partner of the new Museum of London, due to open in West Smithfield in 2022. The Goldsmiths' Company and its affiliated Charity have pledged £10 million to the Museum project. This landmark donation goes towards the Museum’s plans to create a spectacular new home for the history of London and its people in the beautiful but disused market buildings at West Smithfield. This follows the news earlier this year that the City of London Corporation and Mayor of London have together pledged £180 million. Counting the donation from the Goldsmiths’ Company and its affiliated Charity, the Museum has £60 million left to raise. A gallery bearing the Goldsmiths’ name will be at the heart of the new Museum, showcasing the Cheapside Hoard together with highlights from the Company’s world-renowned Collection of historic and contemporary silver. Judith Cobham-Lowe, Prime Warden of the Goldsmiths' Company, said: "We are thrilled to be playing our part in the new Museum of London as a Founding Partner. -

The Cheapside Hoard: Known As George Fabian Lawrence (1862- and the Victoria & Albert Museum

Emerald Watch Courtesy of the Museum of London major commercial thoroughfare in the City of Stony Jack and spilt the cache of Cheapside London. Today it is one of the City’s modern Hoard jewels on the floor he recognised how financial centres, but from the late 15th up to precious this stash was. He “set about washing Arts & Antiques Arts the 17th century it was known as Goldsmith’s off the soil and, gradually, tangled chains of Row, the hub of the goldsmiths’ trade when enamelled gold, cameos, intaglios, carbuncles, tenements and shops were occupied by retail assorted gems and hardstones, rings and and manufacturing goldsmiths. pendants were revealed in all their brilliant Why has it taken one hundred years for this splendour”. (*1) In due course he turned the extraordinary cache of jewels to go on display jewels over to the new London Museum, now to the public? The most reliable account the Museum of London. Subsequently other highlights the role of ‘Stony Jack’, better items were bought by the British Museum The Cheapside Hoard: known as George Fabian Lawrence (1862- and the Victoria & Albert Museum. After 1939). It seems Stony Jack had a career as a some sixty years, however, the thorny matter pawnbroker, dealer and collector of antiquities of ownership caused much debate. Finally, in London’s Lost Jewels and was sometimes an employee of both the 1976 the Hoard was given to the new Museum Guildhall and London museums. But he of London, a combination of the Guildhall by Abby Cronin was also well known for his dealings with Museum and London Museum. -

Jewellery in Autumn

October 2013 / Volume 22 / No. 7 The Hong Kong Show Alphabet Jewels Undercover on 47th St. on FacebookVisit us Meet the international Gemworld in Munich ! Photo: Atelier Tom Munsteiner October 25 — 27, 2013 Europe’s top show for gems & jewellery in autumn www.gemworldmunich.com Gems&Jewellery / October 2013 t Editorial Gems&Jewellery Keep it simple Look through the articles in this issue and you can see the dichotomy in our field. There is Oct 13 stuff about gemmology — detecting heat-treated tanzanite for example (page 7) — and stuff about lack of disclosure in the trade, like the need for clarification about diamonds (page 17). Contents There are expert gemmologists in the world and many people who earn their living buying and selling gems. It should be simple to link the expertise of the former with the business 4 needs of the latter. So why isn’t it? The CIBJO Blue Books on gems, all three of them, present guidelines to gem nomenclature and how to describe and disclose. They are worthy and comprehensive. Compiling and re-compiling them has taken untold hours at meetings around the world over the passing decades, even eroding serious drinking time at CIBJO congresses, but just how effective and Gem News useful are they? I have come to the conclusion that they are confusing for gemmologists, perplexing for the trade and incomprehensible to the public? They are just too complex. They don’t need to be complicated. You really only need three categories of gem 6 (in addition to synthetics and imitations): untreated natural gems, those that have undergone permanent treatment without addition of other substances (just heat and/or irradiation for example), and those which have been modified and are not durable or have had some extraneous substance added (e.g. -

LONDON OFFICE Quoted Equity Team

LONDON OFFICE Quoted Equity Team Our London office, located in the City, is home to our Quoted Equity team, responsible for our fund management services. This team manages PFS Chelverton UK Equity Income Fund and PFS Chelverton UK Equity Growth Fund (both Open Ended Investment Companies, OEICS), as well as Small Companies Dividend Trust PLC and Chelverton Growth Trust PLC (both Investment Trusts). We are located on Ironmonger Lane, a narrow and historic street of relative calm amongst the bustle of the City, close to the Bank of England. The team look forward to welcoming you. Please note: our Bath based Unquoted Equity team, responsible for Chelverton Investor Club, our Bespoke Unquoted Investment Solutions for Family Offices and our Corporate Funding services may have arranged to meet you at our London office if more convenient. How to find us A: Chelverton Asset Management Limited, Third Floor, 17-20 Ironmonger Lane, London, EC2V 8EP Ironmonger Lane is a one-way street running southbound between Gresham Street and Cheapside. 17- 20 can be found nearer the Gresham Street end of Ironmonger Lane. The entrance to 17-20 is situated to the right of Harry’s Bar. Our offices are shared with our fund marketing partners, Spring Capital. When you arrive, please press Spring Capital/3rd Floor on the buzzer (located to the left of the front door) and a member of the team will let you in. Should you need any assistance please do not hesitate to contact us on +44 (0)20 7222 8989 Traveling to us BY TUBE • The Central, Northern, Waterloo & City, Circle and District lines, and the DLR all operate from Bank & Monument Station, approximately 4 minutes’ walk to Bank and 9 minutes’ walk to Monument. -

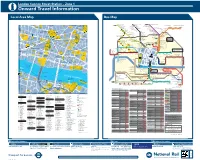

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Palmers Green North Circular Road Friern Barnet Halliwick Park 149 S GRESHAM STREET 17 EDMONTON R 141 1111 Guildhall 32 Edmonton Green 65 Moorgate 12 A Liverpool Street St. Ethelburga’s Centre Wood Green I 43 Colney Hatch Lane Art Gallery R Dutch WALTHAMSTOW F for Reconcilation HACKNEY 10 Church E Upper Edmonton Angel Corner 16 N C A R E Y L A N E St. Lawrence 17 D I and Peace Muswell Hill Broadway Wood Green 33 R Mayor’s 3 T 55 ST. HELEN’S PLACE for Silver Street 4 A T K ING S ’S ARMS YARD Y Tower 42 Shopping City ANGEL COURT 15 T Jewry next WOOD Hackney Downs U Walthamstow E E & City 3 A S 6 A Highgate Bruce Grove RE 29 Guildhall U Amhurst Road Lea Bridge Central T of London O 1 E GUTTER LANE S H Turnpike Lane N St. Margaret G N D A Court Archway T 30 G E Tottenham Town Hall Hackney Central 6 R O L E S H GREEN TOTTENHAM E A M COLEMAN STREET K O S T 95 Lothbury 35 Clapton Leyton 48 R E R E E T O 26 123 S 36 for Whittington Hospital W E LOTHBURY R 42 T T 3 T T GREAT Seven Sisters Lea Bridge Baker’s Arms S T R E E St. Helen S S P ST. HELEN’S Mare Street Well Street O N G O T O T Harringay Green Lanes F L R D S M 28 60 5 O E 10 Roundabout I T H S T K 33 G M Bishopsgate 30 R E E T L R O E South Tottenham for London Fields I 17 H R O 17 Upper Holloway 44 T T T M 25 St. -

The Art of Glassmaking and the Nature of Stones the Role of Imitation in Anselm De Boodt’S Classification of Stones

Sven Dupré The Art of Glassmaking and the Nature of Stones The Role of Imitation in Anselm De Boodt’s Classification of Stones I n Gemmarum et lapidum historia, published in 1609, and arguably the most important work on stones of the seventeenth century, the Flemish physician Anselm De Boodt included precious stones, such as diamonds, lapis lazuli, emeralds (fig. 1), jade, nephrite and agate imported to Europe from Asia and the New World.1 The book was illustrated with specimens from the collection of Rudolf II in Prague where De Boodt was court physician, and the successor of Carolus Clusius as overseer of Rudolf’s gardens.2 De Boodt also included stones mined and sculpted in Europe, such as various marbles, porphyry, alabaster and rock crystal, as well as stones of organic origin, such as amber and coral (fig. 2), some fossils and a diversity of animal body stones, the bezoar stone being the most famous.3 Beyond simply listing stones across the lines between the organic and the inor- ganic, the vegetative and the mineral, the natural and the artificial, as was standard prac- tice in the lapidary tradition stretching back to Theophrastus and Antiquity, De Boodt also offered a classification of stones.D espite his importance, little work has been done on De Boodt. One exception is work by Annibale Mottana, who argues that “De Boot (sic) wanted to show his contempt for the merchant approach to gemstones in an attempt to 1 This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 648718), and has been supported by a Robert H. -

Hall Venue Brochure

MERCERS’ HALL A HISTORIC EVENTS VENUE IN THE CITY OF LONDON A Historic Venue LIVERY COMPANIES 3 Livery companies were originally trade or craft guilds. They were established in the The Mercers’ Company was formally incorporated in 1394 by a birthplace of Thomas Becket. The first Hall, completed in 1524, middle ages to represent the interests of their members within the City of London. royal Charter granted by Richard II. The Company was a trade was built next to the monastery facing onto Cheapside. The term livery refers to robes worn by senior members on ceremonial occasions. guild representing the interests of members who exported woollens and imported silks, velvets, fine linens and other luxury The present Mercers’ Hall is the third to occupy the site. Mercers were merchants who exported English woollens and imported luxury fabrics fabrics. Richard Whittington, William Caxton and Sir Thomas When Henry VIII dissolved the monastery in 1538 the Mercers’ such as silks, velvets and fine linens. Gresham were among the early members of the Company. Company purchased all its properties. The first Hall was burned to the ground in the Great Fire of London in 1666. The Livery companies are ranked in order of ceremonial precedence, established The City of London’s processional thoroughfare of Cheapside second Hall, built directly on the site of the monastery itself, in 1515/16. The Mercers’ Company is ranked number one. Today there are 110 has been the Mercers’ home since the 14th century when they was destroyed by enemy action in 1941. The present third Hall Companies in the City of London, many of them founded since 1945. -

Museological Review: (Re)Visiting Museums

Issue 25, 2021 Museological Review: (Re)visiting Museums The Peer-Reviewed Journal edited by the PhD Students of the School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester www.le.ac.uk/museological-review Museological Review, Issue 25 (Re)visiting Museums Editors-in-Chief Lucrezia Gigante | [email protected] Mingshi Cui | [email protected] Editors Niki Ferraro Isabelle Lawrence Pelin Lyu Blaire Moskowitz Jianan Qi Xiangnuo Ren Cover image: Image generated on https://www.wordclouds.com/. Layout Design: Lucrezia Gigante and Mingshi Cui Contributors: Sophia Bakogianni, Samantha Blickhan, Jessica BrodeFrank, Laura Castro, Alejandra Crescentino, Isabel Dapena, Madeline Duffy, Maxie Fischer, Ana Gago, Juan Gonçalves, Lisa Gordon, Viviana Guajardo, Adriana Guzman Diaz, Amy Hondsmerk, Jessica Horne, Yanrong Jiang, Susanna Jorek, Nick Lake, Chiara Marabelli, Inés Molina Agudo, Megan Schlanker, Stella Toonen, Kristy Van Hoven, Lola Visglerio Gomez, Finn White, Xueer Zou Short and Visual Submissions’ Contributors: Ashleigh Black, Holly Bee, C. Andrew Coulomb, Laura Dudley, Isabell Fiedler, Amber Foster, Olivia Harrer, Blanca Jové Alcade, Krista Lepik, Eloisa E. Rodrigues, Eric W. Ross, Sandra Samolik, Amornchat Sermcheep, Adam Matthew Shery, Joseph Stich Our special thanks to: all anonymous peer-reviewers, Christine Cheesman, Gurpreet Ahluwalia, Dr Isobel Whitelegg, Eloisa Rodrigues and Laura Dudley Contact: School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester, 19 University Road, Leicester LE1 7RF [email protected] © 2021 School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester. All rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the Editors for reproduction of any material in any form, except limited photocopying for educa- tion, non-profit use. Opinions expressed in the publication are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the University of Leicester, the De- partment of Museum Studies, or the editors. -

BAROQUE-ERA ROSE CUTS of COLORED STONES: HIGHLIGHTS from the SECOND HALF of the SEVENTEENTH CENTURY Karl Schmetzer

FEATURE ARTICLES BAROQUE-ERA ROSE CUTS OF COLORED STONES: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE SECOND HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY Karl Schmetzer Colored stones from the Baroque era fashioned as rose cuts have received little attention to date. Even the colored stone rose cuts incorporated in notable collections, such as the Cheapside Hoard discovered in London in 1912, have not been studied in detail, and only very limited further examples are depicted and described in gemological texts. Re- cent work with five objects of liturgical insignia and electoral regalia belonging originally to the archbishops and prince- electors of Trier and Cologne has thus offered an opportunity to augment available information. All of these pieces date to the second half of the seventeenth century. Although the table cuts from that era were still quite simple, con- sisting of an upper flat table facet surrounded by one or two rows of step-cut facets, the rose cuts were enormously varied and complex while still generally following a symmetrical pattern in the facet arrangement. The goal of the study was to contribute to filling a gap in the historical information on gem cuts by offering an overview of the many rose cuts used for colored stones in the second half of the seventeenth century. ose cuts encompass a variety of faceting roses (6 + 12 facets), and full-Dutch roses (6 + 18 arrangements, all of which lack a flat table (fig- facets), respectively (Eppler and Eppler, 1934; Stran- Rure 1). In contrast to the considerable literature ner, 1953). on the use of rose cuts in diamonds, there has been a Visual evidence of the foregoing historical pro- dearth of information regarding their use in colored gression in diamond cuts is readily found in refer- stones.