Powered by Water, Mmolvray 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Until That Song Is Born”: an Ethnographic Investigation of Teaching and Learning Among Collaborative Songwriters in Nashville

“UNTIL THAT SONG IS BORN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF TEACHING AND LEARNING AMONG COLLABORATIVE SONGWRITERS IN NASHVILLE By Stuart Chapman Hill A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Music Education—Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT “UNTIL THAT SONG IS BORN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF TEACHING AND LEARNING AMONG COLLABORATIVE SONGWRITERS IN NASHVILLE By Stuart Chapman Hill With the intent of informing the practice of music educators who teach songwriting in K– 12 and college/university classrooms, the purpose of this research is to examine how professional songwriters in Nashville, Tennessee—one of songwriting’s professional “hubs”—teach and learn from one another in the process of engaging in collaborative songwriting. This study viewed songwriting as a form of “situated learning” (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and “situated practice” (Folkestad, 2012) whose investigation requires consideration of the professional culture that surrounds creative activity in a specific context (i.e., Nashville). The following research questions guided this study: (1) How do collaborative songwriters describe the process of being inducted to, and learning within, the practice of professional songwriting in Nashville, (2) What teaching and learning behaviors can be identified in the collaborative songwriting processes of Nashville songwriters, and (3) Who are the important actors in the process of learning to be a collaborative songwriter in Nashville, and what roles do they play (e.g., gatekeeper, mentor, role model)? This study combined elements of case study and ethnography. Data sources included observation of co-writing sessions, interviews with songwriters, and participation in and observation of open mic and writers’ nights. -

Classic Gray a Stylish Terrace at a New Italian Auditorium Secrets of Self-Levelers

2010/11 Decorative Concrete Buyer’s Guide Vol. 10 No. 4 • May/June 2010 • $6.95 ® Classic Gray A stylish terrace at a new Italian auditorium Secrets of Self-Levelers MARCH 15–18, 2011 NASHVILLE www.ConcreteDecorShow.com A Professional Trade Publications Magazine Have You Topp e d Yo u r s e l f Lately? Concrete Decor magazine is seeking submissions for the 2010 Concrete Countertop Design Competition. Submit your favorite projects today! Countertop submissions may be submitted in two categories: Residential and Commercial/Public. Each entry will be evaluated by a panel of experts on the following criteria: - Aesthetic appeal - Functionality - Creativity and originality - Design challenges that were overcome - How well the countertop complements its surroundings Each entry must include a brief explanation of the project, describing the ways in which it meets these criteria. Entries must also include print-quality photos of the finished project. Winners will receive prize packages worth more than $1,000 supplied by our industry- leading sponsors. Note: Only projects completed on or after January 1, 2009, are eligible. Deadline: All entries must be submitted by July 14, 2010. To enter: Access the nomination form at www.concretedecor.net/Forms/ Concrete_Countertop_Contest.cfm Questions? Contact: [email protected] (877) 935-8906 x204 SPONSORED BY Publisher’s Letter Dear Readers, I was talking with one of our advertisers this past week, and we agreed that business is steadily improving. Refl ecting on our days as contractors, May/June 2010 • Volume 10 we also were of the opinion that any contractor who Issue No. 4 • $6.95 wants to be busy will fi nd the work. -

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

An Advanced Songwriting System for Crafting Songs That People Want to Hear

How to Write Songs That Sell _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ An Advanced Songwriting System for Crafting Songs That People Want to Hear By Anthony Ceseri This is NOT a free e-book! You have been given one copy to keep on your computer. You may print out one copy only for your use. Printing out more than one copy, or distributing it electronically is prohibited by international and U.S.A. copyright laws and treaties, and would subject the purchaser to expensive penalties. It is illegal to copy, distribute, or create derivative works from this book in whole or in part, or to contribute to the copying, distribution, or creating of derivative works of this book. Furthermore, by reading this book you understand that the information contained within this book is a series of opinions and this book should be used for personal entertainment purposes only. None of what’s presented in this book is to be considered legal or personal advice. Published by: Success For Your Songs Visit us on the web at: http://www.SuccessForYourSongs.com Copyright © 2012 by Success For Your Songs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. How to Write Songs That Sell 3 Table of Contents Introduction 6 The Methods 8 Special Report 9 Module 1: The Big -

INTERVIEWS from the 90'S

INTERVIEWS FROM THE 90’s 1 INTERVIEWS FROM THE 90’S p4. THE SONG TALK INTERVIEW, 1991 p27. THE AGE, APRIL 3, 1992 (MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA) p30. TIMES THEY ARE A CHANGIN'.... DYLAN SPEAKS, APRIL 7, 1994 p33. NEWSWEEK, MARCH 20, 1995 p36. EDNA GUNDERSEN INTERVIEW, USA TODAY, MAY 5, 1995 p40. SUN-SENTINEL TODAY, FORT LAUDERDALE, SEPT. 29, 1995 p45. NEW YORK TIMES, SEPT. 27, 1997 p52. USA TODAY, SEPT. 28, 1997 p57. DER SPIEGEL, OCT. 16, 1997 p66. GUITAR WORLD MAGAZINE, MARCH 1999 Source: http://www.interferenza.com/bcs/interv.htm 2 3 THE SONG TALK INTERVIEW, 1991 Bob Dylan: The Song Talk Interview. By: Paul Zollo Date: 1991 Transcribed from GBS #3 booklet "I've made shoes for everyone, even you, while I still go barefoot" from "I and I" By Bob Dylan Songwriting? What do I know about songwriting? Bob Dylan asked, and then broke into laughter. He was wearing blue jeans and a white tank-top T-shirt, and drinking coffee out of a glass. "It tastes better out of a glass," he said grinning. His blonde acoustic guitar was leaning on a couch near where we sat. Bob Dylan's guitar . His influence is so vast that everything that surrounds takes on enlarged significance: Bob Dylan's moccasins. Bob Dylan's coat . "And the ghost of 'lectricity howls in the bones of her face Where these visions of Johanna have now taken my place. The harmonicas play the skeleton keys and the rain And these visions of Johanna are now all that remain" from "Visions of Johanna" Pete Seeger said, "All songwriters are links in a chain," yet there are few artists in this evolutionary arc whose influence is as profound as that of Bob Dylan. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Lage, Analyse und Perspektive österreichischer Musiker im Forschungsfeld der FM4 Charts 2011 unter Berücksichtigung deutscher und/oder englischer Texte. Verfasser Roland Maurer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 316 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Musikwissenschaft Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Regine Allgayer-Kaufmann 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ……………………........…...……………………………...... 4 2. Problemstellung und Erkenntnisinteresse …....…………………….... 7 2.1. Forschungsfragen ….......…………………………………………...... 9 2.2. Forschungshypothesen …………………………………………….... 9 2.3. Erhebungsgegenstand ……………………………………….………. 10 2.4. Stand der Forschung …………………………………………………. 11 THEORETISCHE VERANKERUNG 3. IFPI Austria Musikbericht 2011 …............................……………….... 13 4. Forschungsfeld Radio FM4 ………………………………………….... 17 4.1 Musikauswahl, Marktsituation, FM4 Charts ………………………... 19 4.2. Position, Sprache, Formate …………………………………............. 21 4.3. Auftrag, HörerInnen, Radio FM4 Off Air ………………................... 22 4.4. FM4 Radio Sessions, FM4 Überraschungskonzerte, FM4 Soundpark 23 Exkurs 1: Jugendkultur ……………………………………………………....... 25 Exkurs 2: Independent vs. Popularmusik ………………………………........ 26 5. Sprache in der Musik ………………………………………………...... 33 6. Bandscout ……………………………………………………................ 35 6.1. Rahmenbedingungen, die sich von Bandscout ableiten …........... 36 6.1.1. Anzahl der Live-Konzerte ! Booking ……………………… 36 6.1.2. Größe -

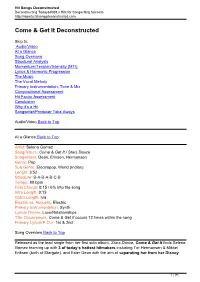

Come & Get It<Span Class="Orangetitle"> Deconstructed

Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com Come & Get It Deconstructed Skip to: Audio/Video At a Glance Song Overview Structural Analysis Momentum/Tension/Intensity (MTI) Lyrics & Harmonic Progression The Music The Vocal Melody Primary Instrumentation, Tone & Mix Compositional Assessment Hit Factor Assessment Conclusion Why it’s a Hit Songwriter/Producer Take Aways Audio/Video Back to Top At a Glance Back to Top Artist: Selena Gomez Song/Album: Come & Get It / Stars Dance Songwriters: Dean, Eriksen, Hermansen Genre: Pop Sub Genre: Electropop, World (Indian) Length: 3:52 Structure: B-A-B-A-B-C-B Tempo: 80 bpm First Chorus: 0:15 / 6% into the song Intro Length: 0:15 Outro Length: n/a Electric vs. Acoustic: Electric Primary Instrumentation: Synth Lyrical Theme: Love/Relationships Title Occurrences: Come & Get It occurs 12 times within the song Primary Lyrical P.O.V: 1st & 2nd Song Overview Back to Top Released as the lead single from her first solo album, Stars Dance, Come & Get It finds Selena Gomez teaming up with 3 of today’s hottest hitmakers including Tor Hermansen & Mikkel Eriksen (both of Stargate), and Ester Dean with the aim of separating her from her Disney 1 / 71 Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com past and to establish her as a major force within the mainstream Pop scene alongside contemporaries including Rihanna, Katy and Britney. As you’ll see within the report, Come & Get It possesses many of the “hit qualities” that are indicative of today’s chart-topping songs, but it also falls short in some key areas that preclude it from realizing its fullest potential. -

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

Two New Orleans Stories

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-16-2003 My Kind of Music: Two New Orleans Stories Mary-Louise Ruth University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Ruth, Mary-Louise, "My Kind of Music: Two New Orleans Stories" (2003). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 16. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/16 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MY KIND OF MUSIC: TWO NEW ORLEANS STORIES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing by Mary-Louise Ruth B.A., University of New Orleans, 1970 Education Credential, St. Mary’s College, 1987 May 2003 Copyright 2003, Mary-Louise Ruth ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank all of my teachers and fellow students for their perceptive comments, criticisms and support which will inspire me for the rest of my life. -

![3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1496/3-smack-that-eminem-feat-eminem-akon-shady-convict-2571496.webp)

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM thing on Get a little drink on (feat. Eminem) They gonna flip for this Akon shit You can bank on it! [Akon:] Pedicure, manicure kitty-cat claws Shady The way she climbs up and down them poles Convict Looking like one of them putty-cat dolls Upfront Trying to hold my woodie back through my Akon draws Slim Shady Steps upstage didn't think I saw Creeps up behind me and she's like "You're!" I see the one, because she be that lady! Hey! I'm like ya I know lets cut to the chase I feel you creeping, I can see it from my No time to waste back to my place shadow Plus from the club to the crib it's like a mile Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini away Gallardo Or more like a palace, shall I say Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Plus I got pal if your gal is game TaeBo In fact he's the one singing the song that's And possibly bend you over look back and playing watch me "Akon!" [Chorus (2X):] [Akon:] Smack that all on the floor I feel you creeping, I can see it from my Smack that give me some more shadow Smack that 'till you get sore Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini Smack that oh-oh! Gallardo Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Upfront style ready to attack now TaeBo Pull in the parking lot slow with the lac down And possibly bend you over look back and Convicts got the whole thing packed now watch me Step in the club now and wardrobe intact now! I feel it down and cracked now (ooh) [Chorus] I see it dull and backed now I'm gonna call her, than I pull the mack down Eminem is rollin', d and em rollin' bo Money -

Interview with Brian Robison by Forrest Larson for the Music at MIT

Music at MIT Oral History Project Herb Pomeroy Interviewed by Forrest Larson with Frederick Harris, Jr. April 5, 2000 Interview no. 2 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lewis Music Library Transcribed by: University of Connecticut, Center for Oral History, Tapescribe, from the audio recording Transcript Proof Readers: Lois Beattie, Jennifer Peterson Transcript Editor: Forrest Larson ©2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lewis Music Library, Cambridge, MA ii Table of Contents 1. Coming to MIT (00:00–CD1 00:00) ...........................................................................1 Klaus Liepman—decision to direct Techtonians—Bill Evans—Chuck Israels—Scott LaFaro— John LaPorta—Richie Orr—Jamshied Sharifi—Jim O'Dell—John Corley 2. The Jazz Bands at MIT (10:58–CD1 10:58) .................................................................4 MIT students as musicians—formation of a second band and hiring Everett Longstreth— audition process—musical experience and development of MIT students—Eliot Jekowsky— Richie Orr—Bill Hurd—Ray Santisi 3. Sound, arrangements, and repertoire (35:38–CD1 35:38) ..........................................12 musical styles—vocalists –instrumentation—Berklee faculty and students—commissions for MIT Jazz Bands—Ellington Principle—solo adaptation —jazz repertoire philosophy—Dave Chapman—Paul Fontaine—Bill Grossman—Alf Clausen—Harvey (Howard?) Boles—Stu (Stuart) Schulman —Clarke Terry—Bob Mintzer—Glenn Reyer -Bob Lawrence—Seb (Sebastian) Bonaiuto—Hal Crook—Stan Kenton—Woody Herman, Maynard Ferguson— Tiger -

Homosociality and Black Masculinity in Gangsta Rap Music

J Afr Am St (2011) 15:22–39 DOI 10.1007/s12111-010-9123-4 ARTICLES Brotherly Love: Homosociality and Black Masculinity in Gangsta Rap Music Matthew Oware Published online: 20 March 2010 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 Abstract Hip hop, specifically gangsta rap music, reflects a stereotypical black masculine aesthetic. The notion of a strong black male—irreverent, angry, defiant and many times violent—is pervasive in gangsta rap music. This badman trope, as characterized by Robin Kelley (1996), oftentimes encompasses hypermasculinity, misogyny, and homophobia. It should come as no surprise that this genre of rap music is rife with sexist themes and lyrics. Yet, what has not been fully explored are the progressive ways that male rappers express themselves towards others considered comrades or “homies.” Homosociality (Bird 1996; Sedgwick 1995), non-sexual positive social bonds, exists in gangsta rap music between men. This study explores the notion of homosociality in this genre of music, analyzing the lyrics of male rap artists who have sold one million or more of their compact discs, for a total of 478 songs. I attempt to further unpack the idea of hegemonic black masculinity, presenting an alternative understanding of its deployment and manifestation in this music. Keywords Black masculinity . Hip hop . Rap . Homosociality Gangsta rap music, the most popular selling subgenre of rap music, is predicated on an essentialized and limited construction of black masculinity. Various scholars have discussed the notion of black male authenticity within rap music (Kitwana 2002; Ogbar 2007; Rose 2008). Many rappers construct a black male subjectivity that incorporates the notion that masculinity means exhibiting extreme toughness, invulnerability, violence and domination (Anderson 1990, 1999; Collins 2005; Majors and Billson 1992; Neal 2006).