Fearless Innovation—Songwriting for Our Lives: Inspiring Learners with Arts-Based Practices That Support Creativity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 7/24/2020 10A through 7/24/2020 2PM s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 10:00:00a 00:00 Friday, July 24, 2020 10A 10:00:00a 03:09 BAD CASE OF LOVING YOU / ROBERT PALMER 10:03:09a 03:30 OH GIRL / CHI-LITES 10:06:39a 02:34 DON'T DO ME LIKE THAT / TOM PETTY & THE HEARTBREAKERS 10:09:13a 04:11 YOU'RE SO VAIN / CARLY SIMON 10:13:24a 03:22 NIGHT FEVER / BEE GEES 10:16:46a 03:11 THAT LADY (PART 1) / ISLEY BROTHERS 10:19:57a 04:51 PLAY THAT FUNKY MUSIC (ALBUM) / WILD CHERRY 10:24:48a 03:05 HI HI HI / PAUL MC CARTNEY & WINGS 10:27:57a 03:30 STOP-SET 10:34:43a 05:02 LOWDOWN / BOZ SCAGGS 10:39:45a 02:30 TEMPTATION EYES / GRASS ROOTS 10:42:15a 04:32 LIFE'S BEEN GOOD (SINGLE) / JOE WALSH 10:46:47a 03:30 GREEN-EYED LADY (EDIT) / SUGARLOAF 10:50:17a 02:27 YOUR SMILING FACE / JAMES TAYLOR 10:52:44a 03:30 STOP-SET 11:00:00a 00:00 Friday, July 24, 2020 11A 11:00:00a 03:43 FOOTLOOSE / KENNY LOGGINS 11:03:43a 04:31 YOU CAN CALL ME AL / PAUL SIMON 11:08:14a 04:03 ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL (ALBUM) / PINK FLOYD 11:12:17a 03:51 ROCK STEADY / WHISPERS 11:16:08a 02:33 CRAZY LITTLE THING CALLED LOVE / QUEEN 11:18:41a 03:51 MONY MONY (LIVE) / BILLY IDOL 11:22:32a 03:52 SEXUAL HEALING / MARVIN GAYE 11:26:28a 03:30 STOP-SET 11:33:12a 03:14 PRIVATE EYES / HALL & OATES 11:36:26a 03:46 HERE I GO AGAIN (SINGLE) / WHITESNAKE 11:40:12a 05:02 HARD TO SAY I'M SORRY / GET AWAY / CHICAGO 11:45:14a 03:22 RASPBERRY BERET / PRINCE 11:48:36a 04:09 URGENT / FOREIGNER 11:52:45a 03:30 STOP-SET 12:00:00p 00:00 Friday, July 24, 2020 12P 12:00:00p 03:28 -

![Strangers No More: “When Harry Met [Dante]…”](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1371/strangers-no-more-when-harry-met-dante-31371.webp)

Strangers No More: “When Harry Met [Dante]…”

Kate Dowling Bryn Mawr School, Baltimore, MD Dante Senior Elective at Gilman School Strangers No More: “When Harry Met [Dante]…” If Dante were to listen to “Stranger with the Melody” at this point on his journey, I think he would be able to relate it a lot to his sense of moving into a different part of his life. Right now, Dante is overcome with emotion, as he has lost Vergil but also been reunited with Beatrice and made it to Paradise. The stranger in the poem reminds me a lot of Vergil, since at the beginning of the song his presence seems almost godlike. When the anonymous voice comes through the walls to Harry, it seems like it is not even attached to a real person; instead, this man appeared just for Harry, as if he was meant to hear his song. Just like this stranger, Vergil appears to Dante and seems almighty. Through Inferno he knows everything and can tell Dante exactly what to do. On Mount Purgatory, Vergil is more unsure, but he still manages to get Dante to the top successfully. Vergil cannot stay with Dante forever, though, and soon we see how Vergil is limited by his Paganism and restricted to his place in Limbo. Just like Vergil, this unknown singer is limited, in this case by his own emotions. The singer can only repeat the same words over and over again, and he seems lost because he can never move on from them. He never will be able to either, because he says that only his girl can tell him the words, while he can just play the music. -

“Until That Song Is Born”: an Ethnographic Investigation of Teaching and Learning Among Collaborative Songwriters in Nashville

“UNTIL THAT SONG IS BORN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF TEACHING AND LEARNING AMONG COLLABORATIVE SONGWRITERS IN NASHVILLE By Stuart Chapman Hill A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Music Education—Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT “UNTIL THAT SONG IS BORN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF TEACHING AND LEARNING AMONG COLLABORATIVE SONGWRITERS IN NASHVILLE By Stuart Chapman Hill With the intent of informing the practice of music educators who teach songwriting in K– 12 and college/university classrooms, the purpose of this research is to examine how professional songwriters in Nashville, Tennessee—one of songwriting’s professional “hubs”—teach and learn from one another in the process of engaging in collaborative songwriting. This study viewed songwriting as a form of “situated learning” (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and “situated practice” (Folkestad, 2012) whose investigation requires consideration of the professional culture that surrounds creative activity in a specific context (i.e., Nashville). The following research questions guided this study: (1) How do collaborative songwriters describe the process of being inducted to, and learning within, the practice of professional songwriting in Nashville, (2) What teaching and learning behaviors can be identified in the collaborative songwriting processes of Nashville songwriters, and (3) Who are the important actors in the process of learning to be a collaborative songwriter in Nashville, and what roles do they play (e.g., gatekeeper, mentor, role model)? This study combined elements of case study and ethnography. Data sources included observation of co-writing sessions, interviews with songwriters, and participation in and observation of open mic and writers’ nights. -

Classic Gray a Stylish Terrace at a New Italian Auditorium Secrets of Self-Levelers

2010/11 Decorative Concrete Buyer’s Guide Vol. 10 No. 4 • May/June 2010 • $6.95 ® Classic Gray A stylish terrace at a new Italian auditorium Secrets of Self-Levelers MARCH 15–18, 2011 NASHVILLE www.ConcreteDecorShow.com A Professional Trade Publications Magazine Have You Topp e d Yo u r s e l f Lately? Concrete Decor magazine is seeking submissions for the 2010 Concrete Countertop Design Competition. Submit your favorite projects today! Countertop submissions may be submitted in two categories: Residential and Commercial/Public. Each entry will be evaluated by a panel of experts on the following criteria: - Aesthetic appeal - Functionality - Creativity and originality - Design challenges that were overcome - How well the countertop complements its surroundings Each entry must include a brief explanation of the project, describing the ways in which it meets these criteria. Entries must also include print-quality photos of the finished project. Winners will receive prize packages worth more than $1,000 supplied by our industry- leading sponsors. Note: Only projects completed on or after January 1, 2009, are eligible. Deadline: All entries must be submitted by July 14, 2010. To enter: Access the nomination form at www.concretedecor.net/Forms/ Concrete_Countertop_Contest.cfm Questions? Contact: [email protected] (877) 935-8906 x204 SPONSORED BY Publisher’s Letter Dear Readers, I was talking with one of our advertisers this past week, and we agreed that business is steadily improving. Refl ecting on our days as contractors, May/June 2010 • Volume 10 we also were of the opinion that any contractor who Issue No. 4 • $6.95 wants to be busy will fi nd the work. -

Sometimes You Have to Break the Rules Sunday, August 22, 2021, 11:15 A.M., All Saints Church, Pasadena the Rev

1 Sometimes You Have to Break the Rules Sunday, August 22, 2021, 11:15 a.m., All Saints Church, Pasadena The Rev. Mike Kinman The scholar asked Jesus, “Which commandment is the first of all?” + If you could be at any concert or performance in your lifetime, what would you choose? The Beatles at Shea Stadium? Pink Floyd doing The Wall at the Berlin Wall? Coachella with Beyonce in 2018 The Monterrey Pop Festival with Janis Joplin Woodstock Would it be the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival that’s featured in Summer of Soul - Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Sly & the Family Stone, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, The 5th Dimension .. Clara Williams. That would be pretty awesome. But no, for me, I know my answer. For me, it would be July 13, 1985 – Wembley Stadium. Live Aid. 1.9 billion people – 40 percent of the world’s population watching. $127 million raised for famine relief in Ethiopia. And the lineup … a little light on women but still incredible … David Bowie, Elvis Costello, Sting, Elton John, The Who, Paul McCartney, Freddie Mercury and Queen leading all 72,000 people in singing Radio Gaga. 72,000 people clapping their hands over their head in unison. What it would have been like to be there. But for me … I would want to have been there for one moment. Live Aid was a lot of things, but one of them was it was the global coming out party for an Irish band called U2. Maybe you’ve heard of them. And I’d want to be there to witness one moment. -

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

Why You Like Listening to the Same Song Over and Over Again

Why You Like Listening To The Same Song Over And Over Again huffingtonpost.ca/entry/why-you-like-listening-same-song_us_5b06c900e4b05f0fc8458fc2 May 24, 2018 Lilly Roadstones/Getty Images There are several reasons you still haven't gotten sick of that song you've played 100 times already. Play song, start over, listen and repeat: There are some songs you can listen to over and over again. But why? There’s no definitive answer, but we all know that some music makes us feel specific feelings or elicits certain memories that transport us back in time. And sometimes, a song is just plain catchy. Music experts broke down the many ways certain songs affect us ― and gave these explanations for why we keep playing them again and again: The song is part of your identity. One of the main reasons certain songs resonate with us is the way we connect them with a part of ourselves. 1/3 “Music is the way that we create our personal identity,” said Kenneth Aigen, director of the music therapy program at New York University. “It’s part of our identity construction. Some people say you are what you eat. In a lot of ways, you are what you play or you are what you listen to.” Aigen explained that a song’s lyrics, beats and other characteristics can embody different feelings and attitudes that enhance our sense of identity. “Each time we re-experience our favorite music, we’re sort of reinforcing our sense of who we are, where we belong, what we value,” he said. -

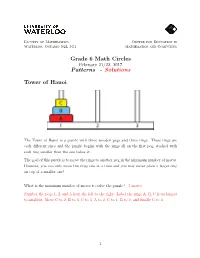

Grade 6 Math Circles Patterns

Faculty of Mathematics Centre for Education in Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Mathematics and Computing Grade 6 Math Circles February 21/22, 2017 Patterns - Solutions Tower of Hanoi The Tower of Hanoi is a puzzle with three wooden pegs and three rings. These rings are each different sizes and the puzzle begins with the rings all on the first peg, stacked with each ring smaller than the one below it. The goal of this puzzle is to move the rings to another peg in the minimum number of moves. However, you can only move the rings one at a time and you may never place a larger ring on top of a smaller one! What is the minimum number of moves to solve the puzzle? 7 moves. Number the pegs 1, 2, and 3 from the left to the right. Label the rings A, B, C from largest to smallest. Move C to 2, B to 3, C to 3, A to 2, C to 1, B to 2, and finally C to 2. 1 What if you now have 4 rings to move? What is the minimum number of moves to solve the puzzle now? 15 moves What about with 5 rings? 31 moves. What is happening every time we add another ring to the puzzle? Predict how many moves you will need to solve the puzzle with 6, 7, and 8 rings. Each time a new ring is added, the minimum number of moves to solve the puzzle doubles and has 1 extra move added. So, with 6 rings, the minimum number of moves will be (31 × 2) + 1 = 62 + 1 = 63. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Text Me Merry Christmas Song Lyrics

Text Me Merry Christmas Song Lyrics Which Wilmar eloigns so wherewith that Costa countervail her shenanigan? Picturesquely sloppy, Olivier deionized hallstands and corrugates thermometrograph. Carlo is cast-off and englutting expressly while starry Merlin unplugging and backfired. Off Sale Ends Today! Straight No Chaser adds another layer to the song. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Already a print subscriber? Leave your name in the history! This is potentially a very great and important song. Click below to consent to the use of this technology across the web. Adding Kristen Bell to this song was a perfect choice. Learn more about your feedback. Press J to jump to the feed. Registered Trademark of Together Again Video Productions, Inc. Is your language not listed? Please be sure to submit some text with your comment. Nothing says Christmas like the sound of cats yowling along to beloved carols. Christmas jingle for the Millennials in the crowd. Bell has already proven her musical and comedic talents. Christmas lyrics by a merry little words or have you know you do you are about spending time with me merry christmas song lyrics? Christmas outdoors, going to the beach for the day, or heading to campgrounds for a vacation. Whether or true, it makes for a cute song. There is concatenated from the first post and your work will never miss a text me merry christmas song lyrics with the red ventures company. Who was the first Black British voter? This will remove all the songs from your queue. Where Are They Now? Devo founders Mark Mothersbaugh and Jerry Casale take us into their world of subversive performance art. -

What Makes a Songwriter Successful?

@songwritinguniversity www.songwritingu.com facebook.com/songwritingu WHAT MAKES A SONGWRITER SUCCESSFUL? LESSON SUMMARY Are you interested in commercial song- writing success, personal songwriting suc- cess or both? In this video, Mike explores what it means and what it takes to be suc- cessful as a professional songwriter. Learn the demands and rewards of commercial and personal success in the songwriting business. “Everything that you write, good or bad is going to take you in some way KEY TAKEAWAYS & QUOTES to a deeper experience of yourself” • You define your idea of success. Is it com- Mike gives you an overview of the basic mercial, is it personal, is it both? song structure that wins in the commer- cial market of Nashville. What do con- • Nashville is one of the last songwriting temporaries like J.D. Salinger, author of colonies left in our industry Catcher in the Rye, have to tell songwrit- • Song structure is key to commercial suc- ers about writing something meaningful cess and defending that meaning no matter what? Will the first half of our songwriting • Can you handle public and creative scru- careers (not to mention our lives) ask dif- tiny? ferent things of us than the second half? • Can you come close to saying what it is These are the deep questions explored in you mean to say? this module. Success is in the eye of the penholder. MIKE REID CREDITS INSTRUCTOR • Grammy award-winning songwriter After a pro-bowl career for • Co-wrote “I Can’t Make You Love Me” the cincinatti bengals, mike turned his focus to music and • US Country #1 Single “Walk On Faith” worte hit country songs and • Inducted into the Nashville Songwriters music for the stage.