Yan Li, Protype for a New Generation a Tribute to a Friend Who Changed My Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 7/24/2020 10A through 7/24/2020 2PM s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 10:00:00a 00:00 Friday, July 24, 2020 10A 10:00:00a 03:09 BAD CASE OF LOVING YOU / ROBERT PALMER 10:03:09a 03:30 OH GIRL / CHI-LITES 10:06:39a 02:34 DON'T DO ME LIKE THAT / TOM PETTY & THE HEARTBREAKERS 10:09:13a 04:11 YOU'RE SO VAIN / CARLY SIMON 10:13:24a 03:22 NIGHT FEVER / BEE GEES 10:16:46a 03:11 THAT LADY (PART 1) / ISLEY BROTHERS 10:19:57a 04:51 PLAY THAT FUNKY MUSIC (ALBUM) / WILD CHERRY 10:24:48a 03:05 HI HI HI / PAUL MC CARTNEY & WINGS 10:27:57a 03:30 STOP-SET 10:34:43a 05:02 LOWDOWN / BOZ SCAGGS 10:39:45a 02:30 TEMPTATION EYES / GRASS ROOTS 10:42:15a 04:32 LIFE'S BEEN GOOD (SINGLE) / JOE WALSH 10:46:47a 03:30 GREEN-EYED LADY (EDIT) / SUGARLOAF 10:50:17a 02:27 YOUR SMILING FACE / JAMES TAYLOR 10:52:44a 03:30 STOP-SET 11:00:00a 00:00 Friday, July 24, 2020 11A 11:00:00a 03:43 FOOTLOOSE / KENNY LOGGINS 11:03:43a 04:31 YOU CAN CALL ME AL / PAUL SIMON 11:08:14a 04:03 ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL (ALBUM) / PINK FLOYD 11:12:17a 03:51 ROCK STEADY / WHISPERS 11:16:08a 02:33 CRAZY LITTLE THING CALLED LOVE / QUEEN 11:18:41a 03:51 MONY MONY (LIVE) / BILLY IDOL 11:22:32a 03:52 SEXUAL HEALING / MARVIN GAYE 11:26:28a 03:30 STOP-SET 11:33:12a 03:14 PRIVATE EYES / HALL & OATES 11:36:26a 03:46 HERE I GO AGAIN (SINGLE) / WHITESNAKE 11:40:12a 05:02 HARD TO SAY I'M SORRY / GET AWAY / CHICAGO 11:45:14a 03:22 RASPBERRY BERET / PRINCE 11:48:36a 04:09 URGENT / FOREIGNER 11:52:45a 03:30 STOP-SET 12:00:00p 00:00 Friday, July 24, 2020 12P 12:00:00p 03:28 -

Entire Dissertation Noviachen Aug2021.Pages

Documentary as Alternative Practice: Situating Contemporary Female Filmmakers in Sinophone Cinemas by Novia Shih-Shan Chen M.F.A., Ohio University, 2008 B.F.A., National Taiwan University, 2003 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Novia Shih-Shan Chen 2021 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY SUMMER 2021 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Novia Shih-Shan Chen Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Thesis title: Documentary as Alternative Practice: Situating Contemporary Female Filmmakers in Sinophone Cinemas Committee: Chair: Jen Marchbank Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Helen Hok-Sze Leung Supervisor Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Zoë Druick Committee Member Professor, School of Communication Lara Campbell Committee Member Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Christine Kim Examiner Associate Professor, Department of English The University of British Columbia Gina Marchetti External Examiner Professor, Department of Comparative Literature The University of Hong Kong ii Abstract Women’s documentary filmmaking in Sinophone cinemas has been marginalized in the film industry and understudied in film studies scholarship. The convergence of neoliberalism, institutionalization of pan-Chinese documentary films and the historical marginalization of women’s filmmaking in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), respectively, have further perpetuated the marginalization of documentary films by local female filmmakers. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Billboard All-Time Adult Contemporary 1000 (Ms-Database Ver.) # C.I

Billboard All-Time Adult Contemporary 1000 (ms-database Ver.) # C.I. 10 Peak wks Peak Date Title Artist 1 124 64 1 17 1999/12/25 I Knew I Loved You Savage Garden 2 123 58 1 11 1998/04/11 Truly Madly Deeply Savage Garden 3 91 74 1 28 2003/06/07 Drift Away Uncle Kracker featuring Dobie Gray 4 94 75 1 11 2001/03/17 I Hope You Dance Lee Ann Womack 5 89 58 1 19 1999/05/29 You'll Be In My Heart Phil Collins 6 88 63 1 15 2001/12/08 Hero Enrique Iglesias 7 95 74 1 2 2001/10/06 If You're Gone matchbox twenty 8 77 67 1 18 2004/10/02 Heaven Los Lonely Boys 9 104 52 2 1 2000/10/07 I Need You LeAnn Rimes 10 92 51 2 5 2000/05/13 Amazed Lonestar 11 70 57 1 18 2005/08/20 Lonely No More Rob Thomas 12 87 58 2 8 2002/05/25 Superman (It's Not Easy) Five For Fighting 13 81 42 1 13 1996/08/10 Change The World Eric Clapton 14 70 50 1 17 2000/04/22 Breathe Faith Hill 15 64 57 1 19 2006/05/13 Bad Day Daniel Powter 16 63 52 1 22 2010/07/03 Hey, Soul Sister Train 17 81 54 1 4 2001/06/16 Thankyou Dido 18 60 52 1 24 2017/05/06 Shape Of You Ed Sheeran 19 81 42 1 8 1998/06/27 You're Still The One Shania Twain 20 82 36 1 12 1999/03/06 Angel Sarah McLachlan 21 85 51 1 1 1999/12/18 That's The Way It Is Celine Dion 22 64 48 1 21 2005/03/12 Breakaway Kelly Clarkson 23 77 47 1 6 2003/11/15 Forever And For Always Shania Twain 24 73 57 1 6 2001/09/29 Only Time Enya 25 58 52 1 20 2011/02/05 Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars 26 72 55 1 9 2006/01/21 You And Me Lifehouse 27 74 50 1 7 2002/09/21 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton 28 57 54 1 18 2016/07/09 Can't Stop The Feeling! Justin -

© 2017 Star Party Karaoke 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 45 Shinedown 98.6 Keith 247 Artful Dodger Feat

Numbers Song Title © 2017 Star Party Karaoke 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 45 Shinedown 98.6 Keith 247 Artful Dodger Feat. Melanie Blatt 409 Beach Boys, The 911 Wyclef Jean & Mary J Blige 1969 Keith Stegall 1979 Smashing Pumpkins, The 1982 Randy Travis 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 1999 Wilkinsons, The 5678 Step #1 Crush Garbage 1, 2 Step Ciara Feat. Missy Elliott 1, 2, 3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys, The 100 Years Five For Fighting 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis & The News 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 18 & Life Skid Row 18 Till I Die Bryan Adams 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin 19-2000 Gorillaz 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 20th Century Fox Doors, The 21 Questions 50 Cent Feat Nate Dogg 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band, The 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 25 Miles Edwin Starr 25 Minutes Michael Learns To Rock 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 29 Nights Danni Leigh 29 Palms Robert Plant 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 30 Days In The Hole Humble Pie 30,000 Pounds Of Bananas Harry Chapin 32 Flavours Alana Davis 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 4 Seasons Of Loneiness Boyz 2 Men 4 To 1 In Atlanta Tracy Byrd 4+20 Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young 42nd Street Broadway Show “42nd Street” 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 4th Of July Shooter Jennings 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 50,000 Names George Jones 50/50 Lemar 500 Miles (Away From Home) Bobby Bare -

A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 2019 Unveiling Identities: A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films Patrick McGuire University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation McGuire, Patrick, "Unveiling Identities: A Cultural Study of the Portrayal of Leading Women in Zhang Yimou Films" (2019). Dissertations. 1736. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1736 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNVEILING IDENTITIES: A CULTURAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYAL OF LEADING WOMEN IN ZHANG YIMOU FILMS by Patrick Dean McGuire A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Communication at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Christopher Campbell, Committee Chair Dr. Phillip Gentile Dr. Cheryl Jenkins Dr. Vanessa Murphree Dr. Fei Xue ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Christopher Dr. John Meyer Dr. Karen S. Coats Campbell Director of School Dean of the Graduate School Committee Chair December.2019 COPYRIGHT BY Patrick Dean McGuire 2019 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT It is imperative to recognize the ongoing collaborations of filmmakers from different countries. -

Music List by Year

Song Title Artist Dance Step Year Approved 1,000 Lights Javier Colon Beach Shag/Swing 2012 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber Foxtrot Boxstep 2019 10,000 Hours Dan and Shay with Justin Bieber Fox Trot 2020 100% Real Love Crystal Waters Cha Cha 1994 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 50 Ways to Say Goodbye Train Background 2012 7 Years Luke Graham Refreshments 2016 80's Mercedes Maren Morris Foxtrot Boxstep 2017 A Holly Jolly Christmas Alan Jackson Shag/Swing 2005 A Public Affair Jessica Simpson Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2006 A Sky Full of Stars Coldplay Foxtrot 2015 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton Slow Foxtrot/Cha Cha 2002 A Year Without Rain Selena Gomez Swing/Shag 2011 Aaron’s Party Aaron Carter Slow Foxtrot 2000 Ace In The Hole George Strait Line Dance 1994 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Foxtrot/Line Dance 1992 Ain’t Never Gonna Give You Up Paula Abdul Cha Cha 1996 Alibis Tracy Lawrence Waltz 1995 Alien Clones Brothers Band Cha Cha 2008 All 4 Love Color Me Badd Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1991 All About Soul Billy Joel Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1993 All for Love Byran Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting Slow/Listening 1993 All For One High School Musical 2 Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2007 All For You Sister Hazel Foxtrot 1991 All I Know Drake and Josh Listening 2008 All I Want Toad the Wet Sprocket Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 All I Want (Country) Tim McGraw Shag/Swing Line Dance 1995 All I Want For Christmas Mariah Carey Fast Swing 2010 All I Want for Christmas is You Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Justin Bieber/Mariah Carey Beach Shag/Swing 2012 -

Chinese Cinema and Transnational Cultural Politics : Reflections on Film Estivf Als, Film Productions, and Film Studies

Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 Volume 2 Issue 1 Vol. 2.1 二卷一期 (1998) Article 6 7-1-1998 Chinese cinema and transnational cultural politics : reflections on film estivf als, film productions, and film studies Yingjin ZHANG Indiana University, Bloomington Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/jmlc Recommended Citation Zhang, Y. (1998). Chinese cinema and transnational cultural politics: Reflections on filmestiv f als, film productions, and film studies. Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese, 2(1), 105-132. This Forum is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Humanities Research 人文學科研究中心 at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報 by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Chinese Cinema and Transnational Cultural Politics: Reflections on Film Festivals, Film Productions, and Film Studies Yingjin Zhang This study situates Chinese cinema among three interconnected concerns that all pertain to transnational cultural politics: (1) the impact of international film festivals on the productions of Chinese films and their reception in the West; (2) the inadequacy of the “Fifth Generation” as a critical term for Chinese film studies; and (3) the need to address the current methodological confinement in Western studies of Chinese cinema. By “transnational cultural politics” here I mean the complicated——and at times complicit— ways Chinese films, including those produced in or coproduced with Hong Kong and Taiwan, are enmeshed in tla larger process in which popular- cultural technologies, genres, and works are increasingly moving and interacting across national and cultural borders” (During 1997: 808). -

CET Syllabus of Record

CET Syllabus of Record Program: CET Chinese Studies and Internship in Shanghai Course Title: Shanghai: Key to Modern China? Course Code: SH/HIST 250 Total Hours: 45 Recommended Credits: 3 Primary Discipline / Suggested Cross Listings: History / East Asian Studies Language of Instruction: English Prerequisites/Requirements: Open to all program students Description The city of Shanghai has had multiple and changing reputations and representations. It has been simultaneously blamed as the source of all that was and is wrong in China and praised as the beacon of an advanced national future. Historically, the city has been China's cotton capital, leading colonial port, the location of its urban modernity, a national center of things from finance to fashion, and the home of radical politics. The objective of this course is to use the social, political, cultural, and economic history of Shanghai to analyze if and how the history of Shanghai provides a key to understanding the making of modern China. After a critical examination of the concepts of tradition and modernity and approaches for studying Shanghai history, we will explore the late imperial, Republican, and People’s Republic periods. The course will end with the Reform and Opening period of the 1980s and the subsequent return of Shanghai to preeminence. Themes will include modernity, commercialism, the role of city's colonial past in shaping its history, and whether Shanghai is somehow unique or representative of what we know as “modern China.” As part of this course, we will take advantage -

Bird's Nest: Herzog & De Meuron in China

61 Documentary Films & DVDs from & about Including 8 NewAsia Releases and 20 Films on DVD for the first time! Bird’s Nest: Herzog & de Meuron in China A Film by Christoph Schaub & Michael Schindhelm Many events of the Beijing 2008 Chinese architects Ai Wei Wei and Olympic Games took place in the Yu Qiu Rong, plus additional commen - brand new, 100,000-seat National tary by cultural advisor Dr. Uli Sigg, the Stadium. Plans for this massive structure former Swiss Ambassador to China. began in 2003, when Swiss architects “Not only exciting architectural Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron were insights, but also a view of the Chinese selected by the Chinese government to mood in times of rapid transition.” design the new stadium, which because of —NZZ its curved steel-net walls was soon dubbed 2008 SilverDocs by locals as the “bird’s nest.” Documentary Festival BIRD’S NEST chronicles this five-year effort, 2008 Cinema de as well as Herzog and de Meuron’s design Paris Festival for a new city district in Jinhua, involving 2008 Solothurner Filmtage, hotels, office and residential buildings. Switzerland Both projects involved complex and often 88 minutes | color | 2008 | Order #AS08-01 difficult negotiations and communications Sale/DVD: $440 between two cultures, two architectural Chapters: traditions and two political systems. 1. Researching Chinese Tradition 2. Conceiving the Design In addition to following the progress of 3. East-West Communication both projects, from initial design and 4. Crisis of Confidence groundbreaking, BIRD’S NEST features 5. Architectural Boom in China 6. Stadium as Public Sculpture interviews with Herzog and de Meuron, 7. -

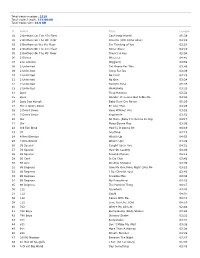

Total Tracks Number: 2218 Total Tracks Length: 151:00:00 Total Tracks Size: 16.0 GB

Total tracks number: 2218 Total tracks length: 151:00:00 Total tracks size: 16.0 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Can't Help Myself 05:39 02 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor Dreams (Will Come Alive) 04:19 03 2 Brothers on the 4th Floor I'm Thinking of You 03:24 04 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Never Alone 04:10 05 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor There's A Key 03:54 06 2 Eivissa Oh La La 04:41 07 2 In a Room Wiggle It 03:59 08 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 03:40 09 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 03:39 10 2 Unlimited No Limit 03:28 11 2 Unlimited No One 03:24 12 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 05:36 13 2 Unlimited Workaholic 03:33 14 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 15 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:34 16 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 17 Three Doors Down Be Like That 04:25 18 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:53 19 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:52 20 3lw No More (Baby I'm Gonna Do Rig 04:17 21 3lw Playa Gonna Play 03:06 22 3rd Eye Blind How Is It Gonna Be 04:10 23 3T Anything 04:15 24 4 Non Blondes What's Up 04:55 25 4 Non Blonds What's Up? 04:09 26 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:25 27 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:40 28 38 Special Second Chance 04:12 29 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 30 50 cent Window Shopper 03:09 31 98 Degrees Give Me One More Night (Una No 03:23 32 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 03:43 33 98 Degrees Invisible Man 04:38 34 98 Degrees My Everything 04:28 35 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 04:27 36 112 Anywhere 04:03 37 112 Cupid 04:07 38 112 Dance With Me 03:41 39 112 Love You Like I Did 04:16 40 702 Where My Girls At 02:44