Chapter 3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

Ghfbooksouthasia.Pdf

1000 BC 500 BC AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500 AD 2000 TAXILA Pakistan SANCHI India AJANTA CAVES India PATAN DARBAR SQUARE Nepal SIGIRIYA Sri Lanka POLONNARUWA Sri Lanka NAKO TEMPLES India JAISALMER FORT India KONARAK SUN TEMPLE India HAMPI India THATTA Pakistan UCH MONUMENT COMPLEX Pakistan AGRA FORT India SOUTH ASIA INDIA AND THE OTHER COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA — PAKISTAN, SRI LANKA, BANGLADESH, NEPAL, BHUTAN —HAVE WITNESSED SOME OF THE LONGEST CONTINUOUS CIVILIZATIONS ON THE PLANET. BY THE END OF THE FOURTH CENTURY BC, THE FIRST MAJOR CONSOLIDATED CIVILIZA- TION EMERGED IN INDIA LED BY THE MAURYAN EMPIRE WHICH NEARLY ENCOMPASSED THE ENTIRE SUBCONTINENT. LATER KINGDOMS OF CHERAS, CHOLAS AND PANDYAS SAW THE RISE OF THE FIRST URBAN CENTERS. THE GUPTA KINGDOM BEGAN THE RICH DEVELOPMENT OF BUILT HERITAGE AND THE FIRST MAJOR TEMPLES INCLUDING THE SACRED STUPA AT SANCHI AND EARLY TEMPLES AT LADH KHAN. UNTIL COLONIAL TIMES, ROYAL PATRONAGE OF THE HINDU CULTURE CONSTRUCTED HUNDREDS OF MAJOR MONUMENTS INCLUDING THE IMPRESSIVE ELLORA CAVES, THE KONARAK SUN TEMPLE, AND THE MAGNIFICENT CITY AND TEMPLES OF THE GHF-SUPPORTED HAMPI WORLD HERITAGE SITE. PAKISTAN SHARES IN THE RICH HISTORY OF THE REGION WITH A WEALTH OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND ISLAM, INCLUDING ADVANCED MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE. GHF’S CONSER- VATION OF ASIF KHAN TOMB OF THE JAHANGIR COMPLEX IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN WILL HELP PRESERVE A STUNNING EXAMPLE OF THE GLORIOUS MOGHUL CIVILIZATION WHICH WAS ONCE CENTERED THERE. IN THE MORE REMOTE AREAS OF THE REGION, BHUTAN, SRI LANKA AND NEPAL EACH DEVELOPED A UNIQUE MONUMENTAL FORM OF WORSHIP FOR HINDUISM. THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECT OF CONSERVATION IS THE PLETHORA OF HERITAGE SITES AND THE LACK OF RESOURCES TO COVER THE COSTS OF CONSERVATION. -

Widening / Improvement of Main Road Leading to Uch Sharif District Bahawalpur

ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) Widening / Improvement of main road leading to Uch Sharif District Bahawalpur (December, 2020) Environment and Social Management Plan (ESMP) Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER-01 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 7 1.1 Project Description ..................................................................... 7 1.2 Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF). 78 1.2.1 Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) ................ 78 1.2.2 Objectives of Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) ................................................................................................... 78 1.3 Scope of Environmental and Social Management Plan ......... 89 1.4 ESMP Methodology .................................................................. 89 I. Literature Review ........................................................................ 89 II. Review of Legal and Policy Frameworks Requirements ............. 89 III. Baseline Data Collection- Environmental and Social Surveys ..... 89 IV. Identification and Assessment of Environmental and Social Impacts Mitigation Measures ........................................................ 9 V. Environmental and Social Impacts Mitigation and Monitoring Plan ................................................................................................. 910 VI. Institutional -

The Ancient Geography of India by Alexander Cunningham

THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY ov INDIA. A ".'i.inMngVwLn-j inl^ : — THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY INDIA. THE BUDDHIST PERIOD, INCLUDING THE CAMPAIGNS OP ALEXANDER, AND THE TRAVELS OF HWEN-THSANG. ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM, Ui.JOB-GBirBBALj BOYAL ENGINEEBS (BENGAL BETIBBD). " Venun et terrena demoDstratio intelligatar, Alezandri Magni vestigiiB insistamns." PHnii Hist. Nat. vi. 17. WITS TSIRTBBN MAPS. LONDON TEUBNER AND CO., 60, PATERNOSTER ROW. 1871. [All Sights reserved.'] {% A\^^ TATLOB AND CO., PEIKTEES, LITTLE QUEEN STKEET, LINCOLN'S INN EIELDS. MAJOR-Q-ENEEAL SIR H. C. RAWLINSON, K.G.B. ETC. ETC., WHO HAS HIMSELF DONE SO MUCH ^ TO THROW LIGHT ON THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY OP ASIA, THIS ATTEMPT TO ELUCIDATE A PARTIODLAR PORTION OF THE SUBJKcr IS DEDICATED BY HIS FRIEND, THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE. The Geography of India may be conveniently divided into a few distinct sections, each broadly named after the prevailing religious and political character of the period which it embraces, as the Brahnanical, the Buddhist^ and the Muhammadan. The Brahmanical period would trace the gradual extension of the Aryan race over Northern India, from their first occupation of the Panjab to the rise of Buddhism, and would comprise the whole of the Pre- historic, or earliest section of their history, duiing which time the religion of the Vedas was the pre- vailing belief of the country. The Buddhist period, or Ancient Geography of India, would embrace the rise, extension, and decline of the Buddhist faith, from the era of Buddha, to the conquests of Mahmud of Ghazni, during the greater part of which time Buddhism was the dominant reli- gion of the country. -

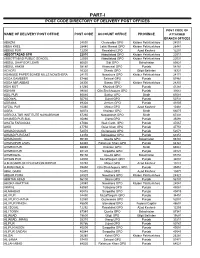

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research ABSTRACT This report documents the technical support provided by the Design Team, deployed by CDPR, and covers the recommendations for institutional and regulatory reforms as well as a proposed private sector participation framework for tourism sector in Punjab, in the context of religious tourism, to stimulate investment and economic growth. Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project ---------------------- (Back of the title page) ---------------------- This page is intentionally left blank. 2 Consortium for Development Policy Research Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS 56 LIST OF FIGURES 78 LIST OF TABLES 89 LIST OF BOXES 910 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1112 1 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 1819 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1819 1.2 PAKISTAN’S TOURISM SECTOR 1819 1.3 TRAVEL AND TOURISM COMPETITIVENESS 2324 1.4 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF TOURISM SECTOR 2526 1.4.1 INTERNATIONAL TOURISM 2526 1.4.2 DOMESTIC TOURISM 2627 1.5 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL HERITAGE / RELIGIOUS TOURISM 2728 1.5.1 SIKH TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 2930 1.5.2 BUDDHIST TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 3536 1.6 DEVELOPING TOURISM - KEY ISSUES & CHALLENGES 3738 1.6.1 CHALLENGES FACED BY TOURISM SECTOR IN PUNJAB 3738 1.6.2 CHALLENGES SPECIFIC TO HERITAGE TOURISM 3940 2 EXISTING INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM SECTOR 4344 2.1 CURRENT INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS 4344 2.1.1 YOUTH AFFAIRS, SPORTS, ARCHAEOLOGY AND TOURISM -

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

MIGRATION AND SMALL TOWNS IN PAKISTAN IIED Workshop, London, 18 – 19 November 2008 Arif Hasan Email: [email protected] PAKISTAN: POLITICAL STRUCTURE • Federation of four provinces • Provinces divided into districts • Districts (103) divided into union councils • Union council (6,022) population 5,000 to 70,000 • Larger cities: city districts divided into towns • Districts, sub-districts, union councils headed by elected nazims (mayors) and naib (deputy) nazims • 33 per cent of all seats reserved for women Pakistan: Population Size, Rural – Urban Ratio and Growth Rate, 1901-1998 Year Population (in ‘000) Proportion Annual Growth Rate Total Rural Urban Rural Urban Total Rural Urban 1901 16,577 14,958 1,619 90.2 9.8 - - - 1911 18,805 17,116 1,689 91.0 9.0 1.27 1.36 0.42 1921 20,243 18,184 2,058 89.8 10.2 0.74 0.61 2.00 1931 22,640 19,871 2,769 87.8 12.2 1.13 0.89 3.01 1941 28,244 24,229 4,015 85.8 14.2 2.24 2.00 3.79 1951 33,740 27,721 6,019 82.2 17.8 1.79 1.36 4.13 1961 42,880 33,240 9,640 77.5 22.5 2.43 1.80 4.84 1971 65,309 48,715 16,594 74.6 25.4 3.67 3.33 4.76 1981 84,253 61,270 23,583 71.7 28.3 3.10 2.58 4.38 1998 130,580 87,544 43,036 68.5 32.5 2.61 2.2 3.5 Source: Prepared from Population Census Reports, Government of Pakistan POVERTY • Human Development Index (UNDP 2006) : 134 out of 177 countries • National poverty line : 32.6 per cent • Poverty incidents has increased post-1992 • Gender related development rank (UNDP 2006) 105 out of 177 countries • Gender empowerment measures rank : 66 out of 177 countries • Impact of structural -

33422717.Pdf

1 Contents 1. PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2. OVERVIEW OF THE CULTURAL ASSETS OF THE COMMUNITIES OF DISTRICTS MULTAN AND BAHAWALPUR ................................................................... 9 3. THE CAPITAL CITY OF BAHAWALPUR AND ITS ARCHITECTURE ............................ 45 4. THE DECORATIVE BUILDING ARTS ....................................................................................... 95 5. THE ODES OF CHOLISTAN DESERT ....................................................................................... 145 6. THE VIBRANT HERITAGE OF THE TRADITIONAL TEXTILE CRAFTS ..................... 165 7. NARRATIVES ................................................................................................................................... 193 8. AnnEX .............................................................................................................................................. 206 9. GlossARY OF TERMS ................................................................................................................ 226 10. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................. 234 11. REPORTS .......................................................................................................................................... 237 12 CONTRibutoRS ............................................................................................................................ -

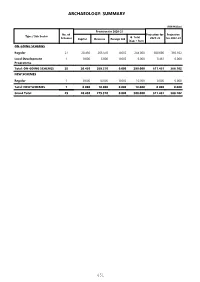

Archaeology: Summary

ARCHAEOLOGY: SUMMARY (PKR Million) Provision for 2020-21 No. of Projection for Projection Type / Sub Sector G. Total Schemes Capital Revenue Foreign Aid 2021-22 for 2022-23 (Cap + Rev) ON-GOING SCHEMES Regular 27 20.430 263.570 0.000 284.000 608.000 366.102 Local Development 1 0.000 6.000 0.000 6.000 3.461 0.000 Programme Total: ON-GOING SCHEMES 28 20.430 269.570 0.000 290.000 611.461 366.102 NEW SCHEMES Regular 1 0.000 10.000 0.000 10.000 0.000 0.000 Total: NEW SCHEMES 1 0.000 10.000 0.000 10.000 0.000 0.000 Grand Total 29 20.430 279.570 0.000 300.000 611.461 366.102 451 Archaeology (PKR Million) Accum. Provision for 2020-21 MTDF Projections Throw fwd GS Scheme Information Est. Cost Exp. G.Total Beyond No Scheme ID / Approval Date / Location Cap. Rev. 2021-22 2022-23 June, 20 (Cap.+Rev.) June, 2023 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ON-GOING SCHEMES Regular 3859 Development and Restoration of 150.299 142.984 0.000 7.315 7.315 0.000 0.000 0.000 Archaeological Sites from Taxila to Swat (Taxila Section), Rawalpindi 01291200016 / 01-07-2012 / Rawalpindi 3860 Improvement and Up-gradation of Taxila 15.607 13.357 0.000 2.250 2.250 0.000 0.000 0.000 Museum 01291604472 / 29-08-2016 / Rawalpindi 3861 Conservation and Restoration of Losar 21.000 1.910 0.000 5.000 5.000 14.090 0.000 0.000 Boali, Wah Cantt, 01291901438 / 21-08-2019 / Rawalpindi 3862 Master Plan for Preservation and 218.094 154.419 0.000 10.000 10.000 27.000 26.675 0.000 Restoration of Rohtas Fort, Jhelum, 01281200011 / 01-07-2012 / Jhelum 3863 Development of Rothas Fort Distt 38.572 19.282 0.000 -

Union Catalogue of Persian Manuscripts in Private Libraries of Pakistan

Dr.Arif Naushahi Professor, Head of Persian Department Gordon College, Rawalpindi, Pakistan [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Cell #+0092 3009753968 Landline #+0092 51 4490224 Union Catalogue of Persian Manuscripts in Private libraries of Pakistan (Vol. 1: Islamic literature) Final Report 1 1. Subcontinent : The hub of manuscripts Presence of Persian language and literature in the subcontinent (Bangladesh, India &Pakistan) since last 1000 years made it a hub of Persian manuscripts. In almost all parts of subcontinent there are centers which have very rich collection of manuscripts known all over the world. Some of these centers are: . Dacca University Library (Dhaka) . Asiatic Society of Bengal (Kolkata) . Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public library (Patna) . Raza Rampur State Library (Rampur) . Andhra Pradesh State Library (formally Asifiya), Hyderabad . Salarjang Museum and Library (Hyderabad) . Azad Library Aligarh Muslim University (Aligarh) 2 nearby Multan) are اوچ As far as Pakistan is concerned, cities like Lahore and Multan (also Uch the Old Persian language and literature centers in Pakistan. The Kashfalmahjub by ‘Ali B.Usman Hujveri, the first Persian book of Islamic mystics was written in Lahore. Nooruddin Muhammad Oufi Bukhari completed his Lubabal albab the Persian tazkara of poets. The most important libraries in Pakistan holding huge number of manuscripts are: . Punjab Public Library (Lahore) . University of the Punjab Central Library (Lahore) . National Museum of Pakistan (Karachi) . Ganjbakhsh Library of Iran-Pakistan Institute of Persian Studies (Islamabad) 2. Background of Compiling of the Union Catalogue of Persian Manuscripts in Pakistan فھرست مشترک نسخہ ھای خطی فارسی The union catalogue of Persian manuscripts of Pakistan compiled by Ahmed Monzavi, Islamabad, 1982-1997, 14 volumes is the only existing example ofپاکستان 3 this kind of catalogue. -

Sufism in South Punjab, Pakistan: from Kingdom to Democracy

132 Journal of Peace, Development and Communication Volume 05, Issue 2, April-June 2021 pISSN: 2663-7898, eISSN: 2663-7901 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.36968/JPDC-V05-I02-12 Homepage: https://pdfpk.net/pdf/ Email: [email protected] Article: Sufism in South Punjab, Pakistan: From kingdom to democracy Dr. Muzammil Saeed Assistant Professor, Department of Media and Communication, University of Author(s): Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Maria Naeem Lecturer, Department of Media and Communication, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Published: 30th June 2021 Publisher Journal of Peace, Development and Communication (JPDC) Information: Saeed, M., & Naeem, M. (2021). Sufism in South Punjab, Pakistan: From kingdom to To Cite this democracy. Journal of Peace, Development and Communication, 05(02), 132–142. Article: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.36968/JPDC-V05-I02-12. Dr. Muzammil Saeed is serving as Assistant Professor at Department of Media and Communication, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Corresponding Author’s Email: [email protected] Author(s) Note: Maria Naeem is serving as Lecturer at Department of Media and Communication, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] From kingdom to democracy 133 Abstract Sufism, the spiritual facet of Islam, emerged in the very early days of Islam as a self- awareness practice and to keep distance from kingship. However, this institution prospered in the times of Muslim rulers and Kings and provided a concrete foundation to seekers for spiritual knowledge and intellectual debate. Sufism in South Punjab also has an impressive history of religious, spiritual, social, and political achievements during Muslim dynasties. -

Final Technical Report on the Results of the UNESCO/Korean Funds-In

UNESCO/Republic of Korea Funds-in-Trust Final Technical Report on the results of the UNESCO/Korean Funds-in-Trust Project: Support for the Preparation for the World Heritage Serial Nomination of the Silk Roads in South Asia, 2013- 2016 2016 Final Technical Report on the results of the UNESCO/Korean Funds-in-Trust project: Support for the Preparation for the World Heritage Serial Nomination of the Silk Roads in South Asia, 2013-2016 Executing Agency: • UNESCO World Heritage Centre, in collaboration with UNESCO Field Offices in Kathmandu and New Delhi Implementing partners: • National Commissions for UNESCO of Bhutan, China, India, and Nepal • Department of Archaeology of Nepal (DoA) • Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) • Division for Conservation of Heritage Sites, Department of Culture, Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs, Royal Government of Bhutan • State Administration of Cultural Heritage of China • ICOMOS International • ICOMOS International Conservation Centre – Xi’an (IICC-X) • University College London, UK Written & compiled by: Tim Williams (Institute of Archaeology, University College London) Edited by: Tim Williams, Roland Lin Chih-Hung (Asia and the Pacific Unit, World Heritage Centre, UNESCO) and Gai Jorayev (Institute of Archaeology, University College London) Prepared for publication by Gai Jorayev at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology ISBN: 978-0-9956132-0-1 Creative commons licence: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. Share, copy and redistribute this publication in any medium or format under the following terms: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit and indicate if changes were made. NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.