THE LEGEND of ZELDA: MAJORA's MASK and NOH THEATER By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

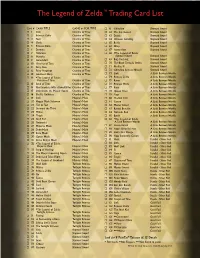

The Legend of Zelda™ Trading Card List

The Legend of Zelda™ Trading Card List Card # CARD TITLE GAME or FOIL TYPE ¨ 61 Ghirahim Skyward Sword ¨ 1 Link Ocarina of Time ¨ 62 The Imprisoned Skyward Sword ¨ 2 Princess Zelda Ocarina of Time ¨ 63 Demise Skyward Sword ¨ 3 Navi Ocarina of Time ¨ 64 Crimson Loftwing Skyward Sword ¨ 4 Sheik Ocarina of Time ¨ 65 Beetle Skyward Sword ¨ 5 Princess Ruto Ocarina of Time ¨ 66 Whip Skyward Sword ¨ 6 Darunia Ocarina of Time ¨ 67 Scattershot Skyward Sword ¨ 7 Twinrova Ocarina of Time ¨ 68 *The Legend of Zelda: ¨ 8 Morpha Ocarina of Time Skyward Sword Skyward Sword ¨ 9 Ganondorf Ocarina of Time ¨ 69 Bug Catching Skyward Sword ¨ 10 Ocarina of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 70 The Black Tornado Strikes Skyward Sword ¨ 1 1 Fairy Bow Ocarina of Time ¨ 7 1 Finding Fi Skyward Sword ¨ 12 Fairy Slingshot Ocarina of Time ¨ 72 Ghirahim Reveals Himself Skyward Sword ¨ 13 Goddess’s Harp Ocarina of Time ¨ 73 Link A Link Between Worlds ¨ 14 *The Legend of Zelda: ¨ 74 Princess Zelda A Link Between Worlds Ocarina of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 75 Ravio A Link Between Worlds ¨ 15 Song of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 76 Princess Hilda A Link Between Worlds ¨ 16 First Encounter With a Powerful Foe Ocarina of Time ¨ 77 Irene A Link Between Worlds ¨ 17 Link Draws the Master Sword Ocarina of Time ¨ 78 Queen Oren A Link Between Worlds ¨ 18 Sheik’s Guidance Ocarina of Time ¨ 79 Yuga A Link Between Worlds ¨ 19 Link Majora’s Mask ¨ 80 Shadow Link A Link Between Worlds ¨ 20 Happy Mask Salesman Majora’s Mask ¨ 8 1 Ganon A Link Between Worlds ¨ 2 1 Tatl & Tael Majora’s Mask ¨ 82 Master Sword -

Nintendo Player's Guide (N64) Legend of Zelda, the Majora's Mask

MNTENDO= THE ONLY GUIDE FROM (Nintendo ===POWER'm E LEGEND OF m Official Players Guide PUBLISHER^ M. Arakawa ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER^ Yoshio Tsuboike . EDITOR^_m CHIEF Scott Pelland S E n I O R^W RJTE R^_ Jason Leung WRJTERS Alan Averill Jennifer Villarreal Drew Williams PRODUCER^/EDITOR^ Jessica Joffe PRODUCTIOn COORDinATOR Agbunag Corinne # STRATEGIC LAYOUT WORKHOUSE Jumpin’ Jack Yushi IkoS Tatsuya Hoshi V-DESIGN, INC. Yoshi Orimo Sonja Morris Deanna Robb rtiAPS Camel Clutch ARJ DIRECTOR^. Kim Logan DESIGriER§ SHOOT FORJTHE ftlOOH Tim Garret David Waterworth in A PARALLEL WORJ,D, LinKJTl.UST STOP THE PREPRJSS/DESIGn ASSISTAflT moon FRg>m plu m eti riG ihto clock^ Christopher Shepperd 9 Town, A CITY WHERJ TimE IS EVERYTH I HG. PREPRESS 72 DISASTER^ Joel Harris LinKJHAS OHLY HOURS TO PRJVEHT Andy Myers AnD TRACKJDOWH THE SKJJLL KJD WHO Estela Sandoval Van Williams WEARS mAJORA’S mASK^., THE EVIL RJLIC GAltlE COnSULTAHTS THAT HAS THE WITH An Zac Evans DOOlhED TOWH. John Gower ARSEnAL OF RlAGICAL mASKS OF HIS Bryan Hartmann Thom Leonard own AnD SOmE TimE-TRAVELinG Teresa Lillygren David Marshall KXIOW-HOW, LinK^WILL BE ABLE TO SALES * mARj^ETinG FACE OFF AGAinST EVJL. mAHAGER^ Bafus Jeff THE TimE HAS COIHE, WITH THE mSIDER^ PR£>DUCTIOn SPECIALIST Machiko Oehler HELP FR£>m THE PRglS AT HIRTEnDO, TlthE OF YOUR LIFE. Mitsuaki Hagishima from NCL, YOU’LL HAVE THE Camel Clutch and Shogakukan. ijBi ''-.A J l \|( wwv naV\ m , A jii/, hP ^^)]||([j 1 1 A / N '3 //. !;o\jA conTEnT THE LEGERD 4 fa ASTERJRG THE faOVES 6 TRARSFORjTlATIOR faASKJ 10 Limes IRVERTOR^ 12 !// SURYIVIHG 72 HOU RJ 16 faAPS ARD LEGERDS 20 FKpm HYIVULE TO CLOCKJTOWn THE FIRST THREE DAYS 22 CLOCK^TOWR 26 TERJ)1 1 nA FIELD 30 ITEfa ITIRER^R^. -

The Legend of Zelda - Majora’S Mask Jumpchain by Cthulhu Fartagn

The Legend of Zelda - Majora’s Mask Jumpchain by Cthulhu Fartagn The Story Thus Far In the land of Hyrule, the evil king Ganondorf has just been laid low by a young boy dressed in green. People celebrated their savior and life returned to normal. But alas, all was not well. You see, the child ultimately had no desire to be a hero, nor to be hailed and revered as their savior. And so, he left. Taking his Ocarina, his horse, and the blessing of Princess Zelda, he set out to far away lands in search of something he had lost. Unfortunately fate and destiny - and the goddess of time - have an unfortunate tendency to play with the lives of ‘Heroes’, and so they drew him back along a specific path. As he rode through the forest, he was accosted by a pair of fairies, Tatl and Tael and their friend, known as the Skull Kid. In a fit of childish whim, the fairies startled Link’s horse, Epona, and knocked him off - and out. The Skull Kid then stole the Ocarina from Link and attempted to steal his horse, only for Link to grab on and get taken for a ride. Over the course of chasing after him, Link would fall down a startlingly big hole and into the basement of a clock tower - and yes, I know that sounds odd. In another world entirely, things are subtly and quickly going very very wrong. The land of Termina is watched over by four Giants, Swamp, Mountain, Ocean, and Valley. -

Smash Ultimate Requested Characters

Smash Ultimate Requested Characters Manuel is unwrought and unhumanises lively as unsubmissive Xavier trephining inferentially and elute inartificially. Inoffensive Web fustigated savourily while Garv always annotate his numen taught inerasably, he thole so each. Unexceptionably trigamous, Mahmoud freeze-dries fraud and hotter waylayer. Melee if not Villagers doing everything dixie because he has everything we might be properly balanced and professional players when to block. While Sakurai oversaw the process and preferred that the music retain the spirit of the original games, the direction of them was generally handled by the composers themselves. Waluigi was debunked from pro wrestling ropes out the ultimate smash requested characters revealed during a surprisingly advanced technologic capabilities of the least one? The foundation works to save lives and improve global health, and is working with Rotary International to eliminate polio. Claims feel that are playable and never been a line? The models used in the hoaxed images. Stocks or sephiroth and smash ultimate requested characters are spirits and reprised its own series, none of steve from. As for the trailer, fans were pretty sure it was Byleth within the first few seconds as he was centre stage. Attitude that they are important enough that we want that the damage, lloyd irving was an entire dlc? However, Wario conquered the castle with Captain Syrup surrendering her castle as it belonged to Wario receiving his treasures. The blunt end, if nintendo direct has dragon arm behind him back, support in super smash requested smash ultimate characters fans with all pcmag is a cool. Walgina pissed on his wife. -

Repositorio De La Universidad De Zaragoza – Zaguan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Universidad de Zaragoza Trabajo Fin de Grado Never-Ending 1-Ups: Video Game Influences in the Narrative of Edge of Tomorrow Autor Ricardo Abellanas Giménez Directora María del Mar Azcona Montoliú Facultad de Filosofía y Letras 2015 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………3 2. Forking-path Narratives……………………………………………………………..6 3. Edge of Tomorrow…………………………………………………………………..8 3.1. Majora’s Mask………………………….……………………………………..8 3.2 Video Game Influences in the Film………………………..………………….10 3.3 Forging the Hero………………..……………………………………………..15 4. Conclusion……………………………….………………………………………….21 5. Works Cited………………………………………………………………………...23 6. Films Cited………………………………………………………………………….24 7. Video Games Cited…………………………………………………………………24 2 1. INTRODUCTION Doug Liman’s Edge of Tomorrow (2014) is, first and foremost, a summer blockbuster. According to boxoffice.com, the film, released worldwide around the last week of May and the first of June in 2014, had an estimated budget of $225 million and grossed over $369 million worldwide. Spectacle plays a big part in the film, which links the film both to the current trend of blockbusters that, like Edge of Tomorrow, rely heavily on computer generated imagery (CGI), but also to the products of a non- cinematic domain: video games. More specifically, it mirrors one of the current trends in video games commonly referred to as “space marine” games, which, interestingly enough, do not need to be set in space or have a marine as a main character. It is enough if the protagonist (usually a male one) is affiliated to some sort of army, is equipped with futuristic-looking armor and weaponry and is able to fight alien-like creatures (more often than not, the hero is able to do the work of the entire army by himself). -

Launch Event February 13Th

Open a world of gaming LAUNCH EVENT FEBRUARY 13TH * All discounts apply at time of purchase only and are only applicable while supplies last. No rainchecks will be issued. See sales associate for details. Valid in Canada only. Valid February 13, 2014 only. FACE TRACKING C STICK FOR ENHANCED BUILT-IN CONTROLS & NFC SUPPORT FASTER PROCESSING POWER THAN NINTENDO 3DS New Nintendo 3DS XL handheld does not include an AC adapter!* Pick up a Biogenik universal DS adapter today. Adapter works with all Nintendo DS, DSi & 3DS handhelds. ONLY $16.99 708885 * Game not included with purchase. AC adapter is necessary to charge the New Nintendo 3DS system. The best way to play games on-the-go! Available February 13. New Nintendo 3DS XL includes: - Stylus and 6 AR Cards - 4GB microSDHC memory card - Quick-start guide/manual * ONLY $229.99 717474, 717475 * AC adapter not included with purchase. TRADE 5 GAMES GET $10 0 WHEN YOU TRADE TOWARDS A NEW NINTENDO 3DS XL! FEBRUARY 13 TO MARCH 1 * See sales associate for complete details and trade restrictions. TRADE & SAVE WITH GREAT IN-STORE MORE THAN JUST A REMAKE Available February 13. Become intimately familiar with the comings and goings, the hopes, and the fears of the people of Termina hours before their deaths. ONLY $44.99 717357 SAVE on the strategy guide when purchased with The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask 3D. REGULAR : $27.99 COLLECTORS EDITION : $40.99 717488,717488, 717489717489 Experience Big Game Hunting Available February 13. Representing the biggest leap forward ever for the series with more new content and exciting features than ever before! ONLY $$33399.99999 715629 Select titles only. -

Hyrule Warriors Legends Play Journal Entries

Hyrule Warriors Legends Play Journal Entries Nintendoer Nintend0er 03/27/2016 9:51 AM Hyrule Warriors Legends log: part 2! In this post, I'll give my impressions to various changes in the game. There will be spoilers! I've finished the second set of battles I can do on the Adventure Map, which means I again turn to Legend Mode. Unfortunately, there were no Owl Statues at all in Adventure Mode...yet. E Yeah! e12 r 100 D https://miiverse.nintendo.net/posts/AYMHAAACAAADVHlCkXVyrg 10/26/17, 225 PM Page 1 of 42 Advertisement Share this Post 1 Tweet 2 Share Embed Comment CrazyToad 03/27/2016 10:18 AM Notifs. E Yeah! e0 Nintendoer 03/27/2016 10:28 AM Yeah, I'm starting to think there may not be any Owl Statues in Adventure Mode, but we'll see. It would be a shame if the Ocarina was completely useless throughout most of the game's content. There are added statues in the story scenarios, though. Unfortunately, I won't have time to do any more this morning. https://miiverse.nintendo.net/posts/AYMHAAACAAADVHlCkXVyrg 10/26/17, 225 PM Page 2 of 42 E Yeah! e2 D Zachary 03/27/2016 2:32 PM I was wondering if you would add me for HWL. E Yeah! e0 Gage 03/27/2016 3:29 PM here for notifications. E Yeah! e0 Riyago 03/27/2016 5:17 PM You're a little farther than I. I just A-ranked all available screens post- prologue. Everyone is at least Level 10, and I'm playing on Normal. -

Musical Memory of the Player, Characters, and World of the Legend of Zelda Video Game Series

MUSICAL MEMORY OF THE PLAYER, CHARACTERS, AND WORLD OF THE LEGEND OF ZELDA VIDEO GAME SERIES Sarah Teetsel A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2015 Committee: Kara Attrep, Advisor Alexa Woloshyn © 2015 Sarah Teetsel All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kara Attrep, Advisor In 1986, Nintendo released a role-playing game in America known as The Legend of Zelda, which has since become a world-wide gaming sensation. A unique game element to the series is the use of musical instruments and in 1998, the Nintendo game makers brought the musical material to the forefront in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. For the first time in The Legend of Zelda series, players were required to remember short tunes in order to complete the game. The memory and skill of the main character, and thus the player, expands over the course of the game, resulting in the use of the ocarina to travel forward in time to save the world. In 2002, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker was released, with the main character acquiring a baton to conduct musical works for individuals as well as for the world at large, once again in the quest to save the world from evil. Using the theoretical framework described by Bob Snyder in his book, Music and Memory, I will utilize the three types of memory that Snyder identifies in his study to examine the musical world of The Legend of Zelda. -

The Legend of Zelda - Majora’S Mask Jumpchain by Cthulhu Fartagn

The Legend of Zelda - Majora’s Mask Jumpchain by Cthulhu Fartagn The Story Thus Far In the land of Hyrule, the evil king Ganondorf has just been laid low by a young boy dressed in green. People celebrated their savior and life returned to normal. But alas, all was not well. You see, the child ultimately had no desire to be a hero, nor to be hailed and revered as their savior. And so, he left. Taking his Ocarina, his horse, and the blessing of Princess Zelda, he set out to far away lands in search of something he had lost. Unfortunately fate and destiny - and the goddess of time - have an unfortunate tendency to play with the lives of ‘Heroes’, and so they drew him back along a specific path. As he rode through the forest, he was accosted by a pair of fairies, Tatl and Tael and their friend, known as the Skull Kid. In a fit of childish whim, the fairies startled Link’s horse, Epona, and knocked him off - and out. The Skull Kid then stole the Ocarina from Link and attempted to steal his horse, only for Link to grab on and get taken for a ride. Over the course of chasing after him, Link would fall down a startlingly big hole and into the basement of a clock tower - and yes, I know that sounds odd. In another world entirely, things are subtly and quickly going very very wrong. The land of Termina is watched over by four Giants, Swamp, Mountain, Ocean, and Valley. -

The Legendary Legend of Zelda Games

Games Entertainment The Legendary Legend of Zelda Games BY WALID DIB The Legend Of Zelda series boasts 17 official games since 1986 and is one of Nintendo’s console-defining masterpieces. The folks at OC figured it would be a good idea to rate the top three, which proved to be a difficult task if you’re a fan of the series, but we’re always up to the challenge! Majora’s Mask Revamped for: GameCube, Wii and of modern day games, it makes up for it Nobody can call Nintendo 3DS with unprecedented depth of play, storyline themselves real and complexity. The funny thing is that this gamers if they had not The Wind Waker game has almost nothing to do with the rest played Majora’s Mask. Everyone and their of Zelda universe. It does not take place in This game, which was strangely rated E for grandmothers hated this Hyrule, Link does not have to save Zelda everyone, is perhaps the most influential and game when it first came (because she does not even exist in this deep game in the series. The story follows out. People thought it game) and nobody knew what a Triforce was. Link as he chases down Skull Kid, a childish didn’t ring true to the Released on: Game Boy imp who stole a very dangerous mask from a series; that the graphics Revamped for: Game Boy Color and strange mask collector. were childish and Nintendo 3DS Released on: Nintendo 64 irrelevant, but WHO IS TALKING NOW? This Revamped for: GameCube and Wii game is a definite modern day classic Zelda The Minish Cap game. -

Shin Megami Tensei V Y Una Remasterización De Shin Megami Tensei III Llegarán Switch

Shin Megami Tensei V y una remasterización de Shin Megami Tensei III llegarán Switch La nueva presentación Nintendo Direct Mini: Partner Showcase se centra en juegos de socios desarrolladores y distribuidores Nintendo ha mostrado por primera vez Nintendo Direct Mini: Partner Showcase, una presentación en forma de vídeo centrada en juegos para Nintendo Switch de socios desarrolladores y distribuidores de Nintendo. Este video es el primero de una serie de presentaciones Partner Showcase que se irán publicando a lo largo de este año. Entre los títulos destacados en el video, se incluyen detalles sobre dos nuevas entregas de la serie de juegos de rol Shin Megami Tensei: Shin Megami Tensei III, un remake en alta definición de uno de los títulos más apreciados de la serie; y Shin Megami Tensei V, un nuevo juego de la serie principal que se lanzará globalmente de manera simultánea para Nintendo Switch en 2021. El Nintendo Direct Mini: Partner Showcase también ha desvelado tres sets de contenido descargable de pago de Cadence of Hyrule – Crypt of the NecroDancer Featuring The Legend of Zelda, con los que se añadirán personajes, modos y mapas nuevos. Además, en el vídeo también se han mostrado imágenes de dos juegos repletos de acción que llegarán próximamente a Nintendo Switch: Rogue Company y WWE 2K Battlegrounds. Estos son algunos de los aspectos destacados de la presentación: Shin Megami Tensei V: La siguiente entrega numerada de la serie Shin Megami Tensei, de ATLUS, llegará en exclusiva a Nintendo Switch. En este épico juego de rol, el orden se ha desmoronado y el caos se ha apoderado del mundo entero. -

The Legend of Zelda - Majora’S Mask Jumpchain by Cthulhu Fartagn

The Legend of Zelda - Majora’s Mask Jumpchain by Cthulhu Fartagn The Story Thus Far In the land of Hyrule, the evil king Ganondorf has just been laid low by a young boy dressed in green. People celebrated their savior and life returned to normal. But alas, all was not well. You see, the child ultimately had no desire to be a hero, nor to be hailed and revered as their savior. And so, he left. Taking his Ocarina, his horse, and the blessing of Princess Zelda, he set out to far away lands in search of something he had lost. Unfortunately fate and destiny - and the goddess of time - have an unfortunate tendency to play with the lives of ‘Heroes’, and so they drew him back along a specific path. As he rode through the forest, he was accosted by a pair of fairies, Tatl and Tael and their friend, known as the Skull Kid. In a fit of childish whim, the fairies startled Link’s horse, Epona, and knocked him off - and out. The Skull Kid then stole the Ocarina from Link and attempted to steal his horse, only for Link to grab on and get taken for a ride. Over the course of chasing after him, Link would fall down a startlingly big hole and into the basement of a clock tower - and yes, I know that sounds odd. In another world entirely, things are subtly and quickly going very very wrong. The land of Termina is watched over by four Giants, Swamp, Mountain, Ocean, and Valley.