SERIATION: Ordering Archaeological Evidence by Stylistic Differences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part II Specialized Studies Chapter Vi

Part II Specialized Studies chapter vi New Sites and Lingering Questions at the Debert and Belmont Sites, Nova Scotia Leah Morine Rosenmeier, Scott Buchanan, Ralph Stea, and Gordon Brewster ore than forty years ago the Debert site exca- presents a model for the depositional history of the site vations signaled a new standard for interdisci- area, including two divergent scenarios for the origins of the Mplinary approaches to the investigation of late cultural materials at the sites. We believe the expanded areal Pleistocene archaeological sites. The resulting excavations extent of the complex, the nature of past excavations, and produced a record that continues to anchor northeastern the degree of site preservation place the Debert- Belmont Paleoindian sites (MacDonald 1968). The Confederacy of complex among the largest, best- documented, and most Mainland Mi’kmaq (the Confederacy) has been increasingly intact Paleoindian sites in North America. involved with the protection and management of the site The new fi nds and recent research have resolved some complex since the discovery of the Belmont I and II sites in long- standing issues, but they have also created new debates. the late 1980s (Bernard et al. 2011; Julien et al. 2008). The Understanding the relative chronologies of the numerous data reported here are the result of archaeological testing site areas and the consequent relationship among the sites associated with these protection eff orts, the development of requires not only understanding depositional contexts for the Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centre (MDCC), and the single occupations but tying together varied contexts (rede- passage of new provincial regulations solely dedicated to pro- posited, disturbed, glaciofl uvial, glaciolacustrine, Holocene tecting archaeological sites in the Debert and Belmont area. -

Archaeological Tree-Ring Dating at the Millennium

P1: IAS Journal of Archaeological Research [jar] pp469-jare-369967 June 17, 2002 12:45 Style file version June 4th, 2002 Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol. 10, No. 3, September 2002 (C 2002) Archaeological Tree-Ring Dating at the Millennium Stephen E. Nash1 Tree-ring analysis provides chronological, environmental, and behavioral data to a wide variety of disciplines related to archaeology including architectural analysis, climatology, ecology, history, hydrology, resource economics, volcanology, and others. The pace of worldwide archaeological tree-ring research has accelerated in the last two decades, and significant contributions have recently been made in archaeological chronology and chronometry, paleoenvironmental reconstruction, and the study of human behavior in both the Old and New Worlds. This paper reviews a sample of recent contributions to tree-ring method, theory, and data, and makes some suggestions for future lines of research. KEY WORDS: dendrochronology; dendroclimatology; crossdating; tree-ring dating. INTRODUCTION Archaeology is a multidisciplinary social science that routinely adopts an- alytical techniques from disparate fields of inquiry to answer questions about human behavior and material culture in the prehistoric, historic, and recent past. Dendrochronology, literally “the study of tree time,” is a multidisciplinary sci- ence that provides chronological and environmental data to an astonishing vari- ety of archaeologically relevant fields of inquiry, including architectural analysis, biology, climatology, economics, -

ARTIFACTS and FEATURES DENDROCHRONOLOGY This

4/28/2004 ARTIFACTS AND FEATURES DENDROCHRONOLOGY This article is one of an occasional series discussing matters archaeological, especially with reference to the Maturango Museum. In previous articles we have talked about why chronologies are important in archaeology, and about a few qualitative techniques for establishing dates or sequences. Today we move on to another topic, quantitative chronological techniques. The first quantitative technique to be developed and applied in archaeology was dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating. It was developed in 1928 by A. E. Douglass of the University of Arizona, an astronomer who was studying sun-spot cycles. He theorized that climatic moisture was affected by the 11-year sun-spot cycle, and concluded that the evidence should be observable in tree rings. In the course of the studies he verified that the climatic sequence of wet and dry years does in fact leave a detectable pattern in the tree ring record: in general, wet years lead to wide rings and dry years to narrow rings. The important byproduct of this for archaeology is that the sequence of wet and dry years in a given locality never repeats itself, so the tree rings contain a unique signature which allows correlating between an old log and a new one, as long as there is some overlap. Douglass, to his credit, realized that his data would be useful to archaeologists, who at that time had no methods for assigning quantitative dates. Qualitative methods such as pottery seriation, stratigraphic excavation, and marker artifacts allow construction of sequences, but not absolute dating. Dendrochronology, for the first time, would allow an archaeologist to assign a date to the event of cutting down a tree to build a structure or use as fuel. -

Strategies and Activities: Preschool

Arkansas Child Development and Early Learning Standards Strategies and Activities: Preschool November 2017 Published 2017 by Early Care and Education Projects Fayetteville, AR 72701 ©Early Care and Education Projects College of Education and Health Professions University of Arkansas All rights reserved December 2017 Strategies and Activities: Preschool page |ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... v Reading and Using Strategies and Activities: Preschool ...................................................................................... vii Books That Support Strategies and Activities: Preschool .................................................................................. 109 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................................... 115 Resources ........................................................................................................................................................... 117 Social and Emotional Development ........................................................................................................................... 1 Cognitive Development ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Physical Development and Health .......................................................................................................................... -

MJ O'brien, RL Lyman

M.J. O'Brien, R.L. Lyman Seriation, Stratigraphy, and Index Fossils The Backbone of Archaeological Dating It is difficult for today's students of archaeology to imagine an era when chronometric dating methods were unavailable. However, even a casual perusal of the large body of literature that arose during the first half of the twentieth century reveals a battery of clever methods used to determine the relative ages of archaeological phenomena, often with considerable precision. Stratigraphic excavation is perhaps the best known of the various relative-dating methods used by prehistorians. Although there are several techniques of using artifacts from superposed strata to measure time, these are rarely if ever differentiated. Rather, common practice is to categorize them under the heading `stratigraphic excavation'. This text distinguishes among the several techniques and argues that stratigraphic excavation tends to result in discontinuous measures of time - a point little appreciated by modern archaeologists. 1999, XIII, 253 p. Although not as well known as stratigraphic excavation, two other methods of relative dating have figured important in Americanist archaeology: seriation and the use of index fossils. The latter (like stratigraphic excavation) measures time discontinuously, while Printed book the former - in various guises - measures time continuously. Perhaps no other method used in archaeology is as misunderstood as seriation, and the authors provide detailed Hardcover descriptions and examples of each of its three different techniques. ▶ 109,99 € | £99.99 | $139.99 ▶ *117,69 € (D) | 120,99 € (A) | CHF 130.00 Each method and technique of relative dating is placed in historical perspective, with particular focus on developments in North America, an approach that allows a more eBook complete understanding of the methods described, both in terms of analytical technique and disciplinary history. -

Dating and Chronology Building - R

ARCHAEOLOGY – Dating and Chronology Building - R. E. Taylor DATING AND CHRONOLOGY BUILDING R. E. Taylor University of California, USA Keywords: Dating methods, chronometric dating, seriation, stratigraphy, geochronology, radiocarbon dating, potassium-argon/argon-argon dating, Pleistocene, Quaternary. Contents 1. Chronological Frameworks 1.1 Relative and Chronometric Time 1.2 History and Prehistory 2. Chronology in Archaeology 2.1 Historical Development 2.2 Geochronological Units 3. Chronology Building 3.1 Development of Historic Chronologies 3.2 Development of Prehistoric Chronologies 3.3 Stratigraphy 3.4 Seriation 4. Chronometric Dating Methods 4.1 Radiocarbon 4.2 Potassium-argon and Argon-argon Dating 4.3 Dendrochronology 4.4 Archaeomagnetic Dating 4.5 Obsidian Hydration Acknowledgments Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary One of the purposes of archaeological research is the examination of the evolution of human cultures.UNESCO Since a fundamental defini– tionEOLSS of evolution is “change over time,” chronology is a fundamental archaeological parameter. Archaeology shares with a number of otherSAMPLE sciences concerned with temporally CHAPTERS mediated phenomenon the need to view its data within an accurate chronological framework. For archaeology, such a requirement needs to be met if any meaningful understanding of evolutionary processes is to be inferred from the physical residue of past human behavior. 1. Chronological Frameworks Chronology orders the sequential relationship of physical events by associating these events with some type of time scale. Depending on the phenomenon for which temporal placement is required, it is helpful to distinguish different types of time scales. ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) ARCHAEOLOGY – Dating and Chronology Building - R. E. Taylor Geochronological (geological) time scales temporally relates physical structures of the Earth’s solid surface and buried features, documenting the 4.5–5.0 billion year history of the planet. -

Americanist Stratigraphic Excavation and the Measurement of Culture Change

Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1999 Americanist Stratigraphic Excavation and the Measurement of Culture Change R. Lee Lyman1 and Michael J. O'Brien1 Many versions of the history of Americanist archaeology suggest there was a "stratigraphic revolution" during the second decade of the twentieth century—the implication being that prior to about 1915 most archaeologists did not excavate stratigraphically. However, articles and reports published during the late nineteenth century and first decade of the twentieth century indicate clearly that many Americanists in fact did excavate stratigraphically. What they did not do was attempt to measure the passage of time and hence culture change. The real revolution in Americanist archaeology comprised an analytical shift from studying synchronic variation to tracking changes in frequencies of artifact types or styles—a shift pioneered by A. V. Kidder, A. L. Kroeber, Nels C. Nelson, and Leslie Spier. The temporal implications of the analytical techniques they developed—frequency seriation and percentage stratigraphy—were initially confirmed by stratigraphic excavation. Within a few decades, however, most archaeologists had begun using stratigraphic excavation as a creational strategy—that is, as a strategy aimed at recovering superposed sets of artifacts that were viewed as representing occupations and distinct cultures. The myth that there was a "stratigraphic revolution" was initiated in the writings of the innovators of frequency seriation and percentage stratigraphy. KEY WORDS: chronology; culture change; stratigraphic excavation; stratigraphic revolution. INTRODUCTION As far as we are aware, Willey (1968, p. 40) was the first historian of Americanist archaeology to use the term "stratigraphic revolution"—in quotation marks—to characterize the fieldwork of, particularly, Manuel 1Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211. -

Teaching Archaeology in the Classroom

Beyond Artifacts: Teaching Archaeology in the Classroom Florida Unearthed, pg. 36 Peanut Butter & Jelly Archaeology, pg. 30 Summer 2008 This page left intentionally blank (ish). Table of Contents Introduction iv Activities General Archaeology (1 class period) Cookie Excavation 1 Cookie Grid 3 Excavación en la galleta 4 Archaeology Jeopardy 6 Archaeology and Pseudoscience 7 Ancient Graffiti 9 Archaeology & the Media 12 Archaeology Goes to the Movies 19 Indiana Jones Script 21 Lara Croft Script 22 Archaeologist Script 23 Prehistoric Archaeology (1 class period) Archaeology Crossword Relay Race 24 Crossword Puzzle 26 What’s Missing ? 27 Worksheet 28 PowerPoint slide 29 Peanut Butter and Jelly Archaeology 30 Arqueología con Crema de Maní y Mermelada 33 Florida Unearthed for Elementary Students 36 Florida Unearthed Board Construction 38 Atlatl Antics 40 Sheet for Throwing Dart by Hand 42 Sheet for Throwing Dart with Atlatl 43 How to make an Atlatl and a Dart 44 Historic Archaeology (1- 2 class periods) Arcadia Sample Lesson: Introduction to Archaeology 47 Arcadia Sample Lesson: Invisible People 49 Arcadia Sample Lesson: Predictive Modeling & 51 the Natural Environment i Underwater Archaeology (1 class period) Build A Boat 53 You Sunk My Battleship! 57 Integrated (multiple class periods/ multiple disciplines) Enriching Traditional Subjects through the Teaching 59 of Archaeology (grades 6-8) Table for Core Courses 61 Sample Math Worksheet 63 Sample Science Worksheet 64 Curriculum (framework) 9-week Archaeology Class for 6th Graders Introduction -

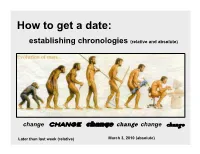

How to Get a Date

How to get a date: establishing chronologies (relative and absolute) change change change change change change Later than last week (relative) March 3, 2010 (absolute) Temporal, or chronological, order • Relative dating – lining things up (before, after) – ‘it is all relative’ • Absolute dating – chronometric dating – actual chronological date assigned – allows measurement of ‘how much’ time has passed between two points Expression of Absolute Dates (culturally specific!) • B.C./A.D. (Before Christ, Anno Domini) • Islamic calendar from A.D. 622 (the Hegira, Mecca to Medina) • B.C.E./C.E. (Before Common Era, Common Era) • B.P. (Before Present) Relative Dating Principle of stratigraphic succession Law of ‘superposition’ (the lower you go, the older you get) Important concepts in geology too Relative Dating Principle of stratigraphic succession Law of ‘superposition’ (the lower you go, the older you get) Typology • Artifact classification into types on the basis of certain similarities… Pots vs. baskets Fine ceramics vs. cooking wares (multiple typologies possible!) • Assumes products of a given place and time have a recognizable style • Styles tend to change through time, but gradually… Unchanging… Constantly changing… Unchanging… Constantly changing… Seriation • Relative dating method involving arranging archaeological materials into a presumed chronological sequence based on cultural and stylistic change • As long as items are gathered from the same cultural tradition, archaeologists assume that stylistic change occurs relatively gradually over time • By tracing similarities and differences in styles and by measuring the relative popularity of these differing styles, one can reconstruct a relative sequence (battleship curve) Seriation ? ? James Deetz seriation studies in New England graveyards Death’s head Cherub Willow and urn ‘battleship curves’ Problems? • Heirlooms • Archaism (‘retro’ looks) (actually a serious issue) Absolute dates Pompeii 24 August A.D. -

An Introduction to the R Package Seriation

Getting Things in Order: An Introduction to the R Package seriation Michael Hahsler Kurt Hornik Southern Methodist University Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien Christian Buchta Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien Abstract Seriation, i.e., finding a suitable linear order for a set of objects given data and a loss or merit function, is a basic problem in data analysis. Caused by the problem’s combinatorial nature, it is hard to solve for all but very small sets. Nevertheless, both exact solution methods and heuristics are available. In this paper we present the package seriation which provides an infrastructure for seriation with R. The infrastructure comprises data structures to represent linear orders as permutation vectors, a wide array of seriation methods using a consistent interface, a method to calculate the value of various loss and merit functions, and several visualization techniques which build on seriation. To illustrate how easily the package can be applied for a variety of applications, a comprehensive collection of examples is presented. Keywords: combinatorial data analysis, seriation, permutation, R. 1. Introduction A basic problem in data analysis, called seriation or sometimes sequencing, is to arrange all objects in a set in a linear order given available data and some loss or merit function in order to reveal structural information. Together with cluster analysis and variable selection, seriation is an important problem in the field of combinatorial data analysis (Arabie and Hubert 1996). Solving problems in combinatorial data analysis requires the solution of discrete optimization problems which, in the most general case, involves evaluating all feasible solutions. Due to the combinatorial nature, the number of possible solutions grows with problem size (number of objects, n) by the order O(n!). -

Measuring Cultural Relatedness Using Multiple Seriation Ordering Algorithms

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Anthropology Faculty Scholarship Anthropology 4-2016 Measuring Cultural Relatedness Using Multiple Seriation Ordering Algorithms Mark E. Madsen University of Washington - Seattle Campus Carl P. Lipo Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/anthropology_fac Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Madsen, Mark E. and Lipo, Carl P., "Measuring Cultural Relatedness Using Multiple Seriation Ordering Algorithms" (2016). Anthropology Faculty Scholarship. 15. https://orb.binghamton.edu/anthropology_fac/15 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Measuring Cultural Relatedness Using Multiple Seriation Ordering Algorithms Mark E. Madsen and Carl P. Lipo Manuscript version: 2016-03-17: 3f6f16a– draft for Electronic Symposium, “Evolutionary Archaeologies: New Approaches, Methods, And Empirical Sufficiency” at the Society for American Archaeology conference, April 2016 Abstract Seriation is a long-standing archaeological method for relative dating that has proven effective in probing regional-scale patterns of inheritance, social net- works, and cultural contact in their full spatiotemporal context. The orderings pro- duced by seriation are produced by the continuity of class distributions and uni- modality of class frequencies, properties that are related to social learning and trans- mission models studied by evolutionary archaeologists. Linking seriation to social learning and transmission enables one to consider ordering principles beyond the classic unimodal curve. -

A Science Curriculum for Preschool Children Based on a Model Designed to Release Human Potential

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1973 A science curriculum for preschool children based on a model designed to release human potential. Gerard Patrick Baruch University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Baruch, Gerard Patrick, "A science curriculum for preschool children based on a model designed to release human potential." (1973). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2786. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2786 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 1973 GERARD PATRICK BARUCH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED m A SCIENCE CURRICULUM FOR PRESCHOOL CHILDREN BASED ON A MODEL DESIGNED TO RELEASE HUMAN POTENTIAL A Dissertation Presented By Gerard Patrick Baruch Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August , 1 973 Major Subject: Education - Human Potential ) A SCIENCE CURRICULUM FOR PRESCHOOL CHILDREN BASED ON A MODEL DESIGNED TO RELEASE HUMAN POTENTIAL A Dissertation Presented By Gerard Patrick Baruch Approved as to style and content by: an (Chairman of Committee) (Head ofHDepartment . Daehler (Member) {T, AcL* Dr. Donald T. Streets (Miember) a . Dr. Leverne Thelen (Member) ff. August, 1973 DEDICATION To my wife, Sylvia, and daughter, Lucita, for their patience, encouragement, and good disposition. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I.