Copyright by Kathleen Oveta Mcelroy 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

Complete Report

FOR RELEASE: THURSDAY, JANUARY 11, 2001, 4:00 P.M. It’s the Economy Again! CLINTON NOSTALGIA SETS IN, BUSH REACTION MIXED Also Inside ... w Hillary's Favorability Rises. w Winners and Losers under Bush. w Powell a Visible Choice. w Clinton's Issue Report Card. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Andrew Kohut, Director Carroll Doherty, Editor Kimberly Parker, Research Director Michael Dimock, Survey Director Nilanthi Samaranayake, Project Director Pew Research Center for The People & The Press 202/293-3126 http://www.people-press.org It’s the Economy Again! CLINTON NOSTALGIA SETS IN, BUSH REACTION MIXED As the country awaits the formal transfer of presidential power, Bill Clinton has never looked better to the American public, while his successor George W. Bush is receiving initial reviews that are more mixed, though still positive. The president leaves office with 61% of the public approving of the way he is handling the job, combined with a surprisingly lofty 64% favorability rating (up from 48% in May 2000). The favorability rating, a mixture of personal and performance evaluations, is all the more impressive because such judgments have never been Clinton’s strong suit. Unlike other recent presidents, Clinton’s ratings have often run below his job approval scores. As historians and scholars render their judgments of Clinton’s legacy, the public is Improved Opinion of the Clintons ... weighing in with a nuanced verdict. By a 60%- Aug May Jan 27% margin, people feel that, in the long run, 1998 2000 2001 Clinton’s accomplishments in office will Bill Clinton ... %%% Favorable 54 48 64 outweigh his failures, even though 67% think he Unfavorable 44 47 34 will be remembered for impeachment and the Don't know 2 5 2 100 100 100 scandals, not for what he achieved. -

Follow a Columnist – 1St Semester

Follow A Columnist – 1st Semester Originated by Jim Veal; modified by S. Ables 2/5/2016 Some of the most prominent practitioners of stylish written rhetoric in our culture are newspaper columnists. Sometimes they are called pundits – that is, sources of opinion, or critics. On the reverse side find a list of well-know newspaper columnists. Select one (or another one that I approve of) and complete the tasks below. Please start a new page and label as TASK # each time you start a new task. TASK 1: Inform Ms. Ables of your selection for the columnist you will follow. DUE THUR/FRI September 15/16 TASK 1—Brief Biography to reveal their bias. DUE TUES/WED September 27/28 — 10 points Write a brief (100-200 word) biography of the columnist. Suggestions of details to include: birthdate, childhood, education, career, previous jobs, awards, unique experiences, etc. I suggest you import a picture of the author if possible. TASK 2—Five Annotated Columns, complete with a Rhetorical Triangle. DUE TUE/WED November 29/30—50 points Make copies from newspapers or magazines or download them from the internet. All articles must come from the current year. I suggest cutting and pasting the columns into Microsoft word and double-spacing them because it makes them easier to annotate and work with. Your annotations should emphasize such things as: - the assertion of the columnist - identify appeals to logos, pathos, or ethos - what rhetorical strategies are being used to support their assertion? - the tone (or tones) of the column - errors of logic (if any) that appear in the column (logical fallacies) - the way the author uses sources, the type of sources the author uses (Be sure to pay attention to this one!) - the apparent audience the author is writing for - in other words, look for all the components in our Rhetorical Triangle. -

The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003

THE REGIME CHANGE CONSENSUS: IRAQ IN AMERICAN POLITICS, 1990-2003 Joseph Stieb A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Wayne Lee Michael Morgan Benjamin Waterhouse Daniel Bolger Hal Brands ©2019 Joseph David Stieb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joseph David Stieb: The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003 (Under the direction of Wayne Lee) This study examines the containment policy that the United States and its allies imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War and argues for a new understanding of why the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. At the core of this story is a political puzzle: Why did a largely successful policy that mostly stripped Iraq of its unconventional weapons lose support in American politics to the point that the policy itself became less effective? I argue that, within intellectual and policymaking circles, a claim steadily emerged that the only solution to the Iraqi threat was regime change and democratization. While this “regime change consensus” was not part of the original containment policy, a cohort of intellectuals and policymakers assembled political support for the idea that Saddam’s personality and the totalitarian nature of the Baathist regime made Iraq uniquely immune to “management” strategies like containment. The entrenchment of this consensus before 9/11 helps explain why so many politicians, policymakers, and intellectuals rejected containment after 9/11 and embraced regime change and invasion. -

Unity Conference, Num- Stay Afloat.” Diversity Be a Fad

TW MAIN 07-21-08 A 19 TVWEEK 7/17/2008 4:33 PM Page 1 SPOTLIGHT ON THE ELECTION TELEVISIONWEEK July 21, 2008 19 BARACK OBAMA’S HISTORIC PRESIDENTIAL BID A HOT TOPIC AT UNITY ... PAGE 20 INSIDE SPECIAL SECTION Keynote Speaker Abdoulaye Wade, President of Senegal NABJ’S Outlook Leaders of the National Association of Black Journalists say the group is focused on the challenge of NewsproTHE STATE OF TV NEWS tough economic times. Page 22 Top Issue for NAHJ Immigration reform remains a key theme for the National Association of Hispanic Journalists. Page 24 Fighting Stereotypes Arab American journalists talk about how 9/11, the war in Iraq and attitudes toward the Middle East affect their work. Page 25 A Broad Spectrum How the AAJA serves its diverse membership while fighting for fairness and accuracy. Page 26 Covering China Bringing the Olympics to a Chinese audience in the U.S. Page 27 Small but Dedicated Native American journalists make sure they’re heard despite their COLORCOLOR relatively small numbers. Page 28 UNITY ‘08 What: Joint conference of the IT UNITY four major associations repre- senting journalists of color, Ebony’s Monroe Explains the Plan as 10,000 held every four years Journalists of Color Gather in Chicago Where: McCormick Place West, Chicago Once every four years the four biggest associations Q&A for journalists of color join forces for a major conference, When: July 23-27 billed as the largest gathering of journalists in the nation. Who: Presented by Unity: Nearly 10,000 participants are expected this week for Unity ’08, tak- Journalists of Color, a coali- ing place July 23-27 at McCormick Place West in Chicago. -

1. “Specifically, Both on Twitter and in TV Appearances, You Have Made

I have deeply valued my time at The Washington Post. And as I said at the beginning of the recent meeting with our executive editor, I am sorry that some of my public statements have angered Post editors. It is true that I have had past conversations with editors about our social media policies. Typically, I spent those meetings seeking specific understanding of precisely where the lines are. It is clear now that top Post editors are more upset than had previously been made clear. Direct and clear communication, even and perhaps especially in moments of frustration and disagreement, are vital to a productive relationship between reporters and their editors. In the same way I would expect an editor to consult me before affixing a correction to one of my stories, I expect that if specific public comments of mine are believed to run afoul of policy that I will be given an opportunity to explain myself prior to being subject to punitive action. I acknowledge that there have been instances in which my tweets or public statements have violated Post policies (it is clear, for example, that I have “criticized competitors”), however the HR sanction I was issued includes factual errors, misstatements about the context and content of my public statements, and sweeping declarations that are unsupported by examples. None of the examples listed in the HR memo are incidents about which I had any discussion with Post editors prior to receiving a formal sanction. I am hopeful that a productive conversation isstill possible, but that cannot happen until the inaccurate HR memo is remedied. -

Enter at Your Own Risk by Maureen Dowd, Pulitzer Prize- Winning Columnist for the New York Times (Putnam; 039915258X)

The Introduction to Bushworld: Enter at Your Own Risk by Maureen Dowd, Pulitzer Prize- Winning Columnist for The New York Times (Putnam; 039915258X) In March 2001, I went to flat and dusty Aggieland, Texas A&M at College Station, to speak at the Bush presidential library. "We had to wait until the Silver Fox left the country to ask you,'' George Herbert Walker Bush told me, only half teasing, since Barbara Bush was abroad. He lured me there by promising to show me an eleven-page comic screed against The New York Times and a few other media miscreants that he'd typed on his computer in the Arthurian style of a column I had written portraying him as the Old King and W. as the Boy King. Like me, 41 has an easier time unfurling his feelings writing than talking, so I especially appreciated his wacky satire about a royal court, sprinkled with words like verily, forsooth and liege, and characters such as King Prescott of Greenwich, George of Crawford, Queen Bar, King Bill, Maid Monica, Hillary the Would-Be Monarch, Knight Algore, Earl Jeb of Tallahassee, Duke Cheney, Warrior Sulzberger, Knight Howell Raines, Knight Ashcroft and Lady Maureen, "charming princess'' of the Times op-ed world. The delicious frolicking, falconing and scheming at the "moatless'' court of the old warrior king, however, will have to forever remain our secret. I was a Times White House reporter for the first Bush administration. Though 41 was always gracious, I know he was disappointed at first to have drawn an irreverent, newfangled "reporterette,'' as Rush Limbaugh would say, who wanted to focus as much on the personalities of leaders as on their policies. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

Pdf-USFWS NEWS

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Fish & Wildlife News National Wildlife Refuge System Centennial Special Edition Spring 2003 Prelude . 1 Table of Director’s Corner: Looking Back, Looking Forward . 2 System of Lands for Wildlife and People for Today and Tomorrow . 3 Contents Future of the Refuge System. 4 Fulfilling the Promise for One Hundred Years . 5 Keeping the Service in the Fish & Wildlife Service . 6 Past . 8 Timeline of Refuge Creation . 9 Shaping the NWRS: 100 Years of History The First 75 Years: A Varied and Colorful History . 12 The Last 25 Years: Our Refuge System . 16 The First Refuge Manager . 18 Pelican Island’s First Survey. 21 CCC Had Profound Effect on Refuge System . 22 Refuge Pioneer: Tom Atkeson . 23 From Air Boats to Rain Gauges . 23 A Refuge Hero Called “Mr. Conservation” . 24 Programs . 25 The Duck Stamp: It’s Not Just for Hunters––Refuges Benefit Too 26 Caught in a Web and Glad of It. 27 Aquatic Resources Conservation on Refuges . 28 To Conserve and Protect: Law Enforcement on Refuges . 29 Jewels of the Prairie Shine Like Diamonds in the Refuge System Crown . 30 Untrammeled by Man . 31 Ambassadors to Alaska: The Refuge Information Technicians Program . 32 Realty’s Role: Adding to the NWRS . 34 Safe Havens for Endangered Species. 34 The Lasting Legacy of Three Fallen Firefighters: Origins of Professional Firefighting in the Refuge System . 35 Part Boot Camp: Part Love-In . 36 Sanctuary and Stewardship for Employees. 37 How a Big, Foreign-Born Rat Came to Personify a Wildlife Refuge Battle with Aquatic Nuisance Species . -

Faith Engaging Culture.” Indeed, the Programs of the Buechner Institute Are an Invitation to Keep the Investigation Invigorated, an Exhortation to Wakefulness

Faith Eugene Peterson Eugene — — imagined venture.” imagined Bristol,TN37620 1350 KingCollegeRoad The “The Buechner Institute is a wonderfully wonderfully a is Institute Buechner “The Director, The Buechner Institute Buechner The Director, BUECHNER INSTITUTE Institute Buechner The Director, Culture Engaging Dale Brown Dale Dale Brown Dale Blessings, Blessings, to drop on in. on drop to Engaging Engaging Faith Faith matter. Hoping for an occasional lightning strike, we invite you you invite we strike, lightning occasional an for Hoping matter. Again this year, we invite you to conversation on matters that that matters on conversation to you invite we year, this Again commenting on the present—paying attention. present—paying the on commenting Culture future, the on ecting refl past, the to listening experience, cultural to wakefulness. That’s what we are up to here, clarifying our our clarifying here, to up are we what That’s wakefulness. to invitation to keep the investigation invigorated, an exhortation exhortation an invigorated, investigation the keep to invitation culture.” Indeed, the programs of the Buechner Institute are an an are Institute Buechner the of programs the Indeed, culture.” series of presentations under the general rubric: “faith engaging engaging “faith rubric: general the under presentations of series Such considerations strike me as excellent fare for a thoughtful thoughtful a for fare excellent as me strike considerations Such this time and place? and time this today, the present. What sort of people ought we to be in in be to we ought people of sort What present. the today, the future. And we get up most mornings wondering about about wondering mornings most up get we And future. -

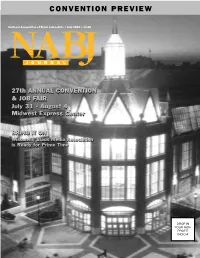

Convention Preview

CONVENTION PREVIEW National Association of Black Journalists • July 2002 • $2.50 27th ANNUAL CONVENTION & JOB FAIR July 31 - August 4 Midwest Express Center BRING IT ON Wisconsinisconsin BlackBlack MediaMedia AssociationAssociation isis ReadyReady forfor PrimePrime TimeTime DROP IN YOUR NON- PROFIT INDICIA Write for the Journal! NABJ Journal — the official publication of the National Association of Black Journalists NABJ Journal, the news magazine of the National Association of Black Journalists, is back with a commitment to serving its readers. But we need you, too. Contribute to the Journal with fascinating stories focusing on the journalism industry, news, trends and personalities affecting African American journalists. To submit stories or ideas, photos or letters, call (301) 445-7100; fax to (301) 445-7101 or e-mail [email protected]. JULY 2002 VOL. 20 NO. 2 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF TABLE OF BLACK JOURNALISTS NABJ Contents Publisher Condace Pressley Editor Rick Sherréll Copy Editors Andre Bowser Sharyn Flanagan Diane Hawkins Jon Perkins Lamar Wilson Contributing Writers Stephania Davis Errin Haines Eugene Kane M.L. Lake Gregory Lee Richard Prince Layout & Design Carolyn Wheeler CEW Productions NABJ Officers African World Festival, Milwaukee, Wisc. Aug. 2-4 President Condace Pressley WSB Radio (Atlanta) Vice President - Vice President - Features Broadcast Print Columns Mike Woolfolk Bryan Monroe From the President 2 WACH-TV (Columbia, S.C) San Jose Mercury News CONVENTION PREVIEW: To Our Readers 3 Secretary Treasurer Career-Wise 16 Gregory Lee Glenn E. Rice The Washington Post The Kansas City Star No longer Ol’ Milwaukee Departments Parliamentarian Immediate The evolution of a Genuine Sharyn Flanagan Past President Chapter Spotlight 5 American City .