Making Cutting-Edge Art with Ballpoint Pens | Artnews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballpoint Basics 2017, Ballpoint Pen with Watercolor Wash, 3 X 10

Getting the most out of drawing media MATERIAL WORLD BY SHERRY CAMHY Israel Sketch From Bus by Angela Barbalance, Ballpoint Basics 2017, ballpoint pen with watercolor wash, 3 x 10. allpoint pens may have been in- vented for writing, but why not draw with them? These days, more and more artists are decid- Odyssey’s Cyclops by Charles Winthrop ing to do so. Norton, 2014, ballpoint BBallpoint is a fairly young medium, pen, 19½ x 16. dating back only to the 1880s, when John J. Loud, an American tanner, Ballpoint pens offer some serious patented a crude pen with a rotat- advantages to artists who work with ing ball at its tip that could only make them. To start, many artists and collec- marks on rough surfaces such as tors disagree entirely with Koschatzky’s leather. Some 50 years later László disparaging view of ballpoint’s line, Bíró, a Hungarian journalist, improved finding the consistent width and tone Loud’s invention using quick-drying of ballpoint lines to be aesthetically newspaper ink and a better ball at pleasing. Ballpoint drawings can be its tip. When held perpendicular to composed of dense dashes, slow con- its surface, Bíró’s pen could write tour lines, crosshatches or rambling smoothly on paper. In the 1950s the scribbles. Placing marks adjacent to one Frenchman Baron Marcel Bich pur- another can create carefully modu- chased Bíró’s patent and devised a lated areas of tone. And if you desire leak-proof capillary tube to hold the some variation in line width, you can ink, and the Bic Cristal pen was born. -

19Th Century Writing Activity: Pen &

Lesson Plan: #NoyesArtatHome 19th Century Writing Activity: Pen & Ink Activity based on letters on display in the Noyes Museum’s Estell Empire Exhibition For ages 12 & up Experience with cursive* writing not necessary Assistance from an adult would be helpful. Overview: Round Hand Script: This was the dominant cursive* writing style among 19th century writing “masters,” whose An account book from John Estell’s general store models were engraved on metal. Letters Circa 1836 – 1837 sloped to the right, and thick lines were © Collection of Stockton University produced on the downstrokes using a flexible, straight-edged (not pointed) pen nib (tip). Thin lines were made by using the corner of the nib. Round hand included decorative swirls referred to as “command of hand.” Copperplate: This type of writing was made with a flexible, pointed metal pen. Copperplate script differs from round hand in the gradual swelling of the broad strokes on curved forms and the narrowness of the backstrokes of b, e, and o. Definitions from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-letter Project Description: This lesson provides a brief overview of handwriting in the 19th century and a hands-on writing activity. First, paint with a teabag to make “old” looking paper. To write, use a quill** pen with black ink or watered-down paint, or a marker. Try to read and copy the example of 19th century writing. Can you write your own name, or a whole letter to a friend? Supplies: 8.5 x 11” piece of paper A tea bag; preferably a darker tea such as black tea (Lipton, Red Rose) A watercolor brush Your choice of: a quill** pen and black ink, watered-down black paint with a fine-tipped brush, or a black marker (for example: Crayola – “broad line” or Sharpie – “fine point,” the newer, the better) *Cursive writing is a style of writing in which all of the letters in a word are connected. -

Writing Instruments 1.800.877.8908 93

92 Russell-Hampton Company WRITING INSTRUMENTS www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 93 Waterman Pens Detail 92 Russell-Hampton Company www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 93 Serving Rotarians Since 1920 A. R66032 Quill® Heritage Roller Ball Pen Features include: newly designed teardrop clip & inlaid feather band, high gloss black lacquer cap, gold accents, fine-point black Roller Ball refill, with full-color slant top Rotary International logo, & handsome display box. Lifetime guarantee. Unit Price $34.95 • Buy 3 $32.95 ea. • Buy 6 $30.95 ea. • Buy 12+ $29.95 ea. B. R66040 Quill® Heritage Roller Ball Pen Elegant teardrop clip and inlaid feather band highlight this beautiful brushed chrome, smooth writing Quill® rollerball pen. Rotary International emblem in crown. Lifetime guarantee. Gift Boxed. Unit Price $34.95 • Buy 3 $33.20 ea. • Buy 6 $31.45 ea. • Buy 12+ $29.70 ea. C. R66012 Waterman® Hemisphere Black Pen & Pencil Set • Classic high gloss black lacquer finish complimented with 23.3-karat gold electroplated clip & trim. Die-struck Rotary emblems affixed to the crowns. Ball pen is fitted with a black ink, medium point refill. Pencil is fitted with 0.5mm lead. Waterman Signature Presentation Blue Box with satin lining. Unit Price $107.95 • Buy 2 $102.50 ea. • Buy 3+ $97.25 ea. D. R66011 Waterman® Hemisphere Black Ball Pen • Same ball pen as sold in above set. Water- man Signature Presentation Blue Box with satin lining. Unit Price $51.95 • Buy 3 $49.35 ea. • Buy 6 $46.85 ea. • Buy 12+ $44.55 ea. -

Za³¹cznik Nr 1 Do SIWZ

Zał ącznik nr 1 do SIWZ 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9 Cena Ilo ść/ jednost Ilo ść/ Ilo ść/ Cena Warto ść miejsce Poda kowa Warto ść jednostka miejsce miejsce Ogółem jednost netto LP. Nazwa asortymentu dostawy tek brutto brutto (kol.4 miary dostawy OR dostawy Ilo ść kowa (kol.4 x PT Nowy VAT (kol. 5 x kol.7) Kraków PT Tarnów netto kol.5) Sącz x kol. 6) 1 CLIPBOARD rozkładany A4 sztuk 10 0 2 12 2 CLIPBOARD rozkładany A5 sztuk 10 0 7 17 3 Cienkopis czarny typu Stabilo, Pentel, Pilot lub Kamet sztuk 100 120 100 320 4 Cienkopis czerwony typu Stabilo, Pentel, Pilot lub Kamet sztuk 100 120 30 250 5 Cienkopis niebieski typu Stabilo, Pentel, Pilot lub Kamet sztuk 100 120 20 240 6 Cienkopis zielony typu Stabilo, Pentel, Pilot lub Kamet sztuk 100 120 20 240 7 Cienkopis kulkowy typu 411 COOL STAEDTLER kolor niebieski sztuk 0 0 10 10 8 Datownik automatyczny typu Trodat 4810 sztuk 50 45 0 95 9 Długopis czarny zwykły typu Stabilo, Pentel lub Pilot sztuk 100 0 0 100 10 Długopis niebieski zwykły typu Stabilo, Pentel lub Pilot sztuk 100 0 0 100 11 Długopis Ŝelowy niebieski typu Stabilo, Pentel lub Pilot sztuk 100 60 0 160 12 Długopis Ŝelowy czarny typu Stabilo, Pentel lub Pilot sztuk 100 60 0 160 13 Długopis Ŝelowy czerwony typu Stabilo, Pentel lub Pilot sztuk 50 60 0 110 14 Długopis przyklejany leŜący na spręŜynce sztuk 30 130 0 160 15 Długopis typu ZENITH, Ballograf, Parker na wkłady wielkopojemne sztuk 50 160 160 370 16 Dziurkacz duŜy typu Esselte, Eagle, Raxel na 60kartek sztuk 20 0 0 20 17 Dziurkacz mały typu Esselte, Eagle, Raxel na 20kartek sztuk 50 20 10 80 18 Dziennik korespondencyjny A4 sztuk 100 120 50 270 19 Flamaster czarny cienki typu Stabilo, Pentel lub Pilot sztuk 100 150 0 250 20 Flamaster czarny gruby typu Stabilo, Pentel lub Pilot sztuk 150 0 0 150 21 Gumka do mazania typu Pentel, Pilot,Pelikan lub Rasoplsast sztuk 50 160 100 310 22 Gumka recepturka duŜa (średnica min: 15 cm) w opakowaniu 1 kg opak. -

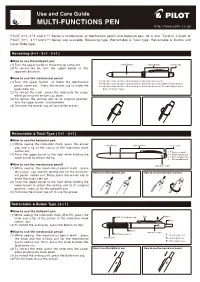

Multi-Functions Pen

Use and Care Guide MULTI-FUNCTIONS PEN http://www.pilot.co.jp/ PILOT 2+1, 3+1 and 4+1 Series-a combination of mechanical pencil and ballpoint pen, all in one. Total of 4 kinds of PILOT 2+1, 3+1 and 4+1 Series are available : Revolving type, Retractable & Twist type, Retractable & Button and Lever Slide type. Revolving (4 +1 . 3 +1 . 2 +1 ) ●How to use the ballpoint pen (1) Turn the upper barrel to make the tip come out. Lower Barrel Upper Barrel Eraser Cap (2) To retract the tip, turn the upper barrel to the opposite direction. ●How to use the mechanical pencil (1) Turn the upper barrel to make the mechanical 2+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen & Red ink ballpoint pen) 3+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen, Red ink ballpoint pen & Blue ink ballpoint pen) pencil come out. Press the eraser cap to make the 4+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen, Red ink ballpoint pen, Blue ink ballpoint pen & lead come out. Green ink ballpoint pen) (2) To retract the lead , press the lead onto the paper while pushing the eraser cap down. (3) To retract the writing unit to its original position, turn the upper barrel anticlockwise. (4) Unscrew the eraser cap off to use the eraser. Retractable & Twist Type ( 3 +1 . 2 +1) ●How to use the ballpoint pen (1) While seeing the indication mark, press the eraser Lower Barrel Upper Barrel Eraser Cap cap and a tip of the colour of the indication mark 0.5 comes out. -

Quill Pen and Nut Ink

Children of Early Appalachia Quill Pen and Nut Ink Grades 3 and up Early writing tools were made from materials people could find or easily make themselves. Children used a slate with chalk and stone to write lessons at schools. They also practiced drawing and writing with a stick in dirt. Penny pencils for slates were available at general stores. Paper was purchased at stores too. Before the invention of pencils and pens, children used carved twigs or goose-quill pens made by the teacher. Ink was made at home from various ingredients (berries, nuts, roots, and soot) and brought to school. Good penmanship was highly valued but difficult to attain. Objective: Students will make pen and ink from natural materials and try writing with these old- fashioned tools. Materials: Pen: feathers, sharp scissors or a pen knife (Peacock or pheasant feathers make wonderful pens, but any large feather from a goose or turkey works well too.) Ink: 10 walnut shells, water, vinegar, salt, hammer, old cloth, saucepan, small jar with lid, strainer. (After using the homemade ink, students make like to continue practicing writing with the quill, so you may want to provide a bottle of manufactured ink for further quill writings.) Plan: Pen: Cut off the end of the feather at a slant. Then cut a narrow slit at the point of the pen. Ink: 1. Crush the shells in cloth with a hammer. 2. Put shells in saucepan with 1 cup of water. Bring to a boil, and then simmer for 45 minutes or until dark brown. -

Pitt Artist Pen Calligraphy !

Pitt Artist Pen Calligraphy ! A new forest project in Colombia secures the livelihoods of small farmers and the Faber-Castell stands for quality wood supply for Faber-Castell – a unique environment protection programme, Founded in 1761, Faber-Castell is one of the world’s oldest industrial companies and is now in certified by the UN. the hands of the eighth generation of the same family. Today it is represented in more than With a socially exemplary and sustainable reforestation project in Colombia, Faber-Castell con- 120 countries. Faber-Castell has its own production sites in nine countries and sales companies tinues to reinforce its leading role as a climate-neutral company. On almost 2,000 hectares of in 23 countries worldwide. Faber-Castell is the world’s leading manufacturer of wood-cased pencils, grassland along the Rio Magdalena in Colombia, small farmers are planting tree seedlings for fu- producing over 2000 million black-lead and colour pencils per year. Its leading position on the ture pencil production. The fast-growing forests not only provide excellent erosion protection for international market is due to its traditional commitment to the highest quality and also the large this region plagued by overgrazing and flooding, they are also a reliable source of income for the number of product innovations. farmers living in modest circumstances, who are paid for forest maintenance and benefit from the Its Art & Graphic range allows Faber-Castell to enjoy a great reputation among artists and hobby proceeds from the timber. The environmental project was one of the first in the world to be certi- painters. -

The Origins of the Musical Staff

The Origins of the Musical Staff John Haines For Michel Huglo, master and friend Who can blame music historians for frequently claiming that Guido of Arezzo invented the musical staff? Given the medieval period’s unma- nageable length, it must often be reduced to as streamlined a shape as possible, with some select significant heroes along the way to push ahead the plot of musical progress: Gregory invented chant; the trouba- dours, vernacular song; Leoninus and Perotinus, polyphony; Franco of Cologne, measured notation. And Guido invented the staff. To be sure, not all historians put it quite this way. Some, such as Richard Hoppin, write more cautiously that “the completion of the four-line staff ...is generally credited to Guido d’Arezzo,”1 or, in the words of the New Grove Dictionary of Music, that Guido “is remembered today for his development of a system of precise pitch notation through lines and spaces.”2 Such occasional caution aside, however, the legend of Guido as inventor of the staff abides and pervades. In his Notation of Polyphonic Music, Willi Apel writes of “the staff, that ingenious invention of Guido of Arezzo.”3 As Claude Palisca puts it in his biography of Guido, it was that medieval Italian music writer’s prologue to his antiphoner around 1030 that contained one of the “brilliant proposals that launched the Guido legend, the device of staff notation.”4 “Guido’s introduction of a system of four lines and four spaces” is, in Paul Henry Lang’s widely read history, an “achievement” deemed “one of the most significant in -

Penmanship Activity Pack

A Day in a One-Room Schoolhouse Marathon County Historical Society Living History Learning Project Penmanship Lesson Activity Packet For Virtual Visits Project Coordinators: Anna Chilsen Straub & Sandy Block Mary Forer: Executive Director (Rev. 6/2020) Note to Participants This packet contains information students can use to prepare for an off-site experience of a one-room school. They may be used by classroom teachers to approximate the experience without traveling to the Little Red Schoolhouse. They are available here for students who might be unable to attend in person for any reason. In addition, these materials may be used by anyone interested in remembering or exploring educational experiences from more than a century ago. The usual lessons at the Little Red Schoolhouse in Marathon Park are taught by retired local school teachers and employees of the Marathon County Historical Society in Wausau, Wisconsin. A full set of lessons has been video-recorded and posted to our YouTube channel, which you can access along with PDFs of accompanying materials through the Little Red Schoolhouse page on our website. These PDFs may be printed for personal or classroom educational purposes only. If you have any questions, please call the Marathon County Historical Society office at 715-842-5750 and leave a message for Anna or Sandy, or email Sandy at [email protected]. On-Site Schoolhouse Daily Schedule 9:00 am Arrival Time. If you attended the Schoolhouse in person, the teacher would ring the bell to signal children to line up in two lines, boys and girls, in front of the door. -

CATALOGUE2020 Sve Webb.Pdf

Redan 1945 började Ballograf sin produktion i ett garage i Göteborg och idag kan vi stoltsera med att vara Sveriges enda penntillverkare. Genom åren har vi kontinuerligt utvecklat och förbättrat våra produkter, så det är med gott samvete vi lämnar livstids garanti på varje penna som lämnar vår fabrik. Vi arbetar med noggrant utvalda material för att kunna garantera att våra pen- nor håller vad vi lovar och vi har fått utmärkelser för vår genomarbetade design. Våra pennor säljs idag framgångsrikt i bland annat Japan, Schweiz, Finland, Italien, Tyskland, Österrike och USA. Idag tillverkas årligen över 5 miljoner kulspetspennor, stiftpennor och tuschpen- nor i fabriken i Filipstad. The story of Ballograf began back in 1945 in a garage in Gothenburg, and today we’re proud to say that we’re the only Swedish pen manufacturer. Through the years we’ve continuously developed and improved our products, so it is with a clear conscience we leave a lifetime guarantee on every pen that leaves our factory. We work with carefully selected materials to ensure that our pens live up to our high standars and we’ve received awards for our elaborate design. Our pens are currently sold successfully in Japan, Switzerland, Finland, Italy, Germany, Austria and the USA. To day Ballograf manufactures over 5 million ballpoint pens, mechanical pencils and markers anually at the factory in Filipstad. 1 2 EXECUTIVE Kulspetspenna Ballpoint Pen Ballograf Permo lanserades på 1950-talet. Nu relanserar vi pennan un- der namnet Executive. Ballograf Executive kombinerar tidlös klassisk penndesign, med modern skrivteknik. Det bästa från 50-talet är bevarat i denna penna, med rena linjer och färg- valet som står i smakfull kontrast till överdelen i metall. -

Handwriting Today . . . and a Stolen American Relic

Reviews Handwriting Today... and A Stolen American Relic WILLIAM BUTTS FLOREY, Kitty Burns. Script and Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwriting. Brooklyn: Melville House Publishing, 2009. 8vo. Hardbound, dust jacket. 190pp. Illustrations. $22.95. HOWARD, David. Lost Rights: The Misadventures of a Stolen Ameri- can Relic. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010. Small 4to. Hardbound, dust jacket. 344pp. $26.00. If you’re anything like me, handling handwriting from many eras on a daily basis, you get sick and tired of the endless refrain from the general public when viewing old documents: “People all had such beautiful handwriting back then!” or, conversely, “No one writes like that today!” Et cetera—ad nauseum. I’ve almost given up refuting these gross generalizations, but “in the old days” I’d pull out letters from, say, Horace Greeley, the Duke of Wellington, a Civil War soldier and other notori- ously illegible scribblers to prove that every age has its share of beautiful penmanship, horrid penmanship and mediocre pen- manship. And as for modern penmanship, most of the examples of current penmanship I see are in the form of personal checks MANUSCRIPTS, VOL. 62 235 NO. 3, SUMMER 2010 236 MANUSCRIPTS (thankfully), and there too I find a mix of beautiful, horrid and mediocre penmanship. The more things change, the more they you-know-what. Which is one beef I have with Kitty Burns Florey in her oth- erwise enjoyable Script and Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwrit- ing. Other than the uninitiated general public cited above, the other group that unfairly bemoans current penmanship are the handwriting snobs (which I don’t consider Florey)—elit- ists whose devotion to pseudo-Palmerian calligraphy or other esoteric specialties blinds them to the simple, honest, unsophis- ticated attractiveness of the day-to-day script of ordinary persons who’ve never studied calligraphy. -

The History of the Ballpoint Pen

89 | Ezra’s Archives My Utilitarian Chinese Memento: The History of the Ballpoint Pen Robert Schur Made in China For all intents and purposes, my three-week sojourn through China should have given me an appreciation for the Chinese people and their culture, a more thorough understanding of life under a Communist regime, and perhaps some knowledge of handy Chinese phrases. Indeed, I left the country with all of those things, but I also found myself fascinated with the most mundane of souvenirs: the ballpoint pen, particularly the one that I acquired while studying at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China, during a trip with fifty other Cornell students sponsored by Cornell University and the Chinese government. When we arrived for our orientation, we found each place set with an array of official University and government forms. Next to these stacks of paper rested green triangular ballpoint pens filled with blue ink, sporting retractable points, each emblazoned with the university’s name, phone number and website. Considering my at-best-rudimentary Chinese language skills, this pen proved quite handy, as I would have been at a loss to ask a hotel clerk or cashier to borrow one. Beyond this small bit of good fortune, I thought little of the pen as I carried it in my pocket throughout the trip until I was making notes on a lecture by one Dr. Wu Xiaobo about the Chinese economy. As he detailed the various aspects of China’s post-Mao era economic reforms, he informed us that 80 percent of all of the world’s pens are made in China, and 70 percent of The History of the Ballpoint Pen | 90 worldwide pen components are made in a particular district, the name of which my sloppy handwriting ironically rendered unintelligible.1 While the veracity of Chinese economic statistics has been hotly contested recently, and reliable data on Chinese ballpoint pen manufacturing data is all but nonexistent, Wu’s remarks nonetheless made me reconsider the oft-overlooked history of the pen that I held in my hands, just one of the billions of ballpoints across the world.